Wherein we glance back at the first week of the #DickensClub reading of Oliver Twist (week sixteen of the Dickens Chronological Reading Club 2022-23); With General Memoranda, a summary of reading and discussion, and a look ahead to week two.

Happy Week 2 of our reading of Oliver Twist, “my flash com-pan-i-ons”!

The workhouse, baby farming, undertaking, pickpocketing, chimney-sweeping…as Chris writes, it is a “horror story with a child at center stage; the narrative with its pointed sarcasm and facetiousness; the un-sugar-coated descriptions of callousness and the soul-wrenching misery it causes; and the commentary on Society’s inhumane treatment of those most in need…Dickens does not ask what is our duty to each other but rather how did we forget that duty?”

Today we have a lot of General Memoranda to cover, but please take a look, as there are some special Thank Yous, including one to our dear Club member, Boze!

General Mems

And this past week, we passed the 100 Day mark in our Club! Three cheers…

If you’re counting, this coming week will be week 16 of the #DickensClub as a whole (and today Day 105), and the second week of Oliver Twist (our third read). Please feel free to comment below this post for the second week’s chapters, or to use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter.

No matter where you’re at in the reading process, a huge “thank you” for reading along with us! We’re forever grateful for shares and retweets from all! Including friends new and old, our marvelous Dickens Fellowship, the Dickens Society, the Dickens Letters Project, Dr. Pete Orford and Dr. Christian Lehmann, and all of our Dickensian heroes, for helping to build our reading community. And a huge thank you to The Circumlocution Office for providing such an online resource for us!

And today I want to send a special and most heartfelt Thank You to our one-and-only Owl! at the Library, Boze Herrington, fellow Dickensian and Club member, for most generously being willing to take on our Introductory posts in future, for each new read!! He is a researcher extraordinaire, like our dear Chris, with a Dickensian delight in detail ~ and I am so excited for his introductions!

Meanwhile, I’ll keep up on these weekly summary and discussion wrap-ups, and add an occasional special-interest post. (If you have any Dickensian special interest topic that you’d like to share with the group ~ and truly, so many comments shared here are so extraordinary, that they would be marvelous separate posts entirely ~ please let us know!)

We’d love to have new readers join us. If you’re interested: the schedule is in my intro post here, and my introduction to Oliver Twist can be found here. If you have been reading along with us but are not yet on the Member List, I would love to add you! Please feel free to message me here on the site, or on twitter.

Week One Oliver Twist Summary (Chapters 1-11)

We are well and truly into the era of the New Poor Law. Oliver Twist “was ushered into this world of sorrow and trouble” in a workhouse, his mother having been found lying in the street the previous night, her shoes “worn to pieces; but where she came from, or where she was going to, nobody knows.” She dies, leaving Oliver to the care of strangers, including a drunken midwife and a medical gentleman who is gone almost as soon as he appeared. Even Oliver’s name is a grudging bestowal from an impersonal system.

“He was badged and ticketed, and fell into his place at once—a parish child—the orphan of a workhouse—the humble, half-starved drudge—to be cuffed and buffeted through the world—despised by all, and pitied by none.”

Not long after, little Oliver is farmed out to “a branch workhouse some three miles off, where twenty or thirty other juvenile offenders against the poor-laws, rolled about the floor all day, without the inconvenience of too much food or too much clothing.” Dickens compares the children’s care by this Mrs. Mann to that of a horse-owner who had experimented with just how little that gentleman could manage to feed the poor animal and still keep it alive. Clearly, many have died under Mrs. Mann’s “care,” and she uses resources for herself which were intended for the children. Mr. Bumble, the parish beadle who had named Oliver, pays a visit, and brings Oliver with him to the workhouse to stand before the board, who declare their intention to educate him into some useful trade.

In the large stone-walled refectory where the boys have their meal, the famous scene ensues: Oliver draws the short straw in a challenge with the other boys ~ one of whom looks about ready to eat his companions ~ and ventures to ask for “more”: for another bowl of the thin gruel that is supposed to sustain them.

The beadle is called for, “Oliver was ordered into instant confinement; and a bill was next morning pasted on the outside of the gate, offering a reward of five pounds to anybody who would take Oliver Twist off the hands of the parish.”

Seeking a drudge assistant and a means to pay off debt all at once, Mr. Gamfield the chimney-sweeper tries to take him, but is prevented by a moment of pity on the part of the magistrate, for Oliver’s obvious terror. Oliver ends up instead with the undertaker, Mr. Sowerberry, and lives for a time among coffins, eating the dog’s leftovers, tormented by the bullying Noah Claypole. Oliver ends up in a fight with Claypole, who has insulted Oliver’s mother, after which Oliver is beaten and locked up.

Finally, Oliver runs away, making the long foot-journey to London. Arriving at its outskirts, weakened from fatigue and hunger, Oliver meets Jack Dawkins, a.k.a. the “artful Dodger,” dressed in a man’s coat and a side-cocked hat. The Dodger assures Oliver that he can have a place to stay with “a ‘spectable old gentleman…wot’ll give you lodgings for nothink.” He leads him through the labyrinth of London at nightfall, through Saffron-hill.

“A dirtier or more wretched place he had never seen. The street was very narrow and muddy, and the air was impregnated with filthy odors…the sole places that seemed to prosper, amid the general blight of the place, were the public-houses…”

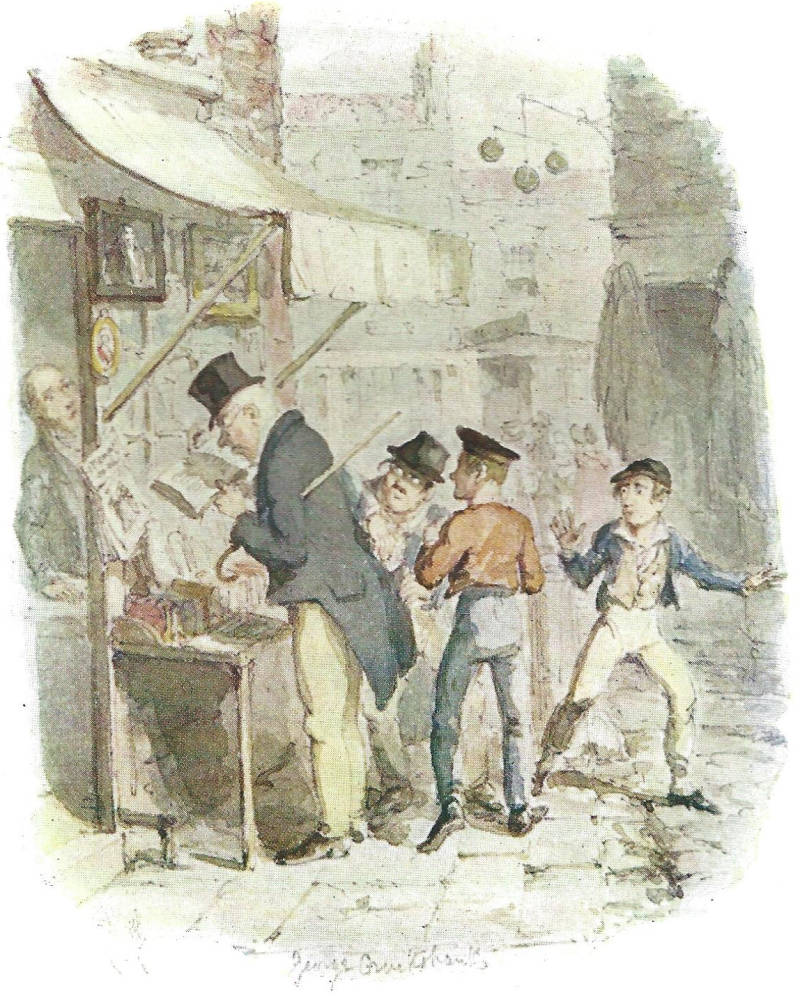

He brings Oliver to a house near Field Lane, and introduces him to Fagin, “a very old shrivelled Jew” who is cooking sausages. (If you haven’t read it yet, please see see Boze’s wonderful piece on Dickens’ very problematic character.) That night, Oliver sees Fagin pulling out a box filled with jewels from a hiding place in the ground, and Fagin is paranoid of being watched. Later, Oliver is introduced to the game Fagin and the boys play, of dodging and pick-pocketing, not understanding the implications until he sees the Dodger do it in real life, taking a handkerchief from the pocket of a gentleman at a book stall. Frightened and horrified, Oliver runs; due to this, he is taken for being the thief, and is pursued and brought before the magistrate.

The gentleman who is robbed, Mr. Brownlow, appears kindly disposed towards the boy, and begins to doubt Oliver’s guilt, when a shop-keeper runs in, and bears witness to the fact that it was not Oliver who was guilty, but two other boys. Oliver faints with weakness, and is taken into a coach by Mr. Brownlow.

Discussion Wrap-Up

This week, after our Introduction to Oliver Twist, we had a lovely supplement in Peter Ackroyd’s introduction (SPOILERS!) shared by our member, Chris.

We also had the wonderful piece by Boze on the antisemitism in Oliver Twist, and the very problematic character of Fagin. I’ll keep linking back to this, since we have a whole other discussion happening there; I won’t try to summarize that conversation in the weekly wrap-ups (except perhaps in the final), as it is a conversation that I’m sure will be ongoing throughout our read. We’ve only just met Fagin, and already a couple of us are hit in the face by the repetition of “the Jew” in relation to him.

Where We’re At

Dana is thoroughly enjoying Jonathan Pryce’s audio reading of Oliver, and is struck by the social commentary ~ the “’angry young man’ mode,” as Chris called it. Steve is bravely finishing Pickwick while he begins; and his comment about not rushing Dickens really sparked a question which Boze and I have been pondering, and we’d love some input, as there are some exciting possibilities…more on this in a post in a day or two. (There’s been some illness in the family and my little niece is going to need her auntie more than usual this week!) So, thank you, Steve, for sparking some wonderful ideas and questions!

The Adaptation Stationmaster loved the scene where Mr. Bumble gets put in his place by the magistrate who has a moment of pity for Oliver.

“Full ‘Angry Young Man’ Mode”

We have been discussing the ironic, painful, dark humor in Oliver, such a contrast from the rambling shenanigans in Pickwick! Every line, it sometimes seems, is bitter, biting, and a jab at the system. Chris wrote beautifully on the experience of rereading this so far, and on the tone of the young, angry Dickens. Here in “gallery mode” (click on each to see enlarged):

Chris M. comments (above)

We’re seeing products of the inhumane system too. The shadow is coming forward, threatening to engulf the light, as Lenny writes:

“Such vicious, sadistic treatment, which involves beatings and starvation, can only be seen as the actions of depraved people who have totally been swallowed by the darker sides of their personalities, venting their angers and frustrations on the innocent subjects who are readymade victims for their wrath. Our Oliver, by chance, is sadly one of them.”

~Lenny H.

And I agree:

Rach M. comments (above)

Entrapment/Claustrophobia; the Place as Image of the Person

Lenny’s first word for us was “Claustrophobia,” and he remarked on how the physical setting is a “dire illustration of Oliver’s state of mind.” (I am curious to see how often we will see this come ’round again in Dickens: the place as illustrative of the person and his/her interior state.)

Lenny discusses a passage in the third chapter where Oliver is imprisoned in a dark and solitary room a week after the “more” incident, and where “the wall, itself, becomes his protective ‘womb'”:

“He only cried bitterly all day; and, when the long, dismal night came on, spread his little hands before his eyes to shut out the darkness, and crouching in the corner, tried to sleep: ever and anon waking with a start and tremble, and drawing himself closer and closer to the wall, as if to feel even its cold hard surface were a protection in the gloom and loneliness which surrounded him.”

Lenny continues:

“Once again, only in a more elaborate way, the confined, dark, cold setting both causes his depression and operates to mirror the horrible and empty feelings he has about his circumstances. As readers we keep hoping that this incarceration motif will only be temporary, and that soon this young boy’s circumstances will improve. But as we can see in the next excerpt, Mrs. Sowerberry’s treatment of him is as sadistically vicious as his other tormentors; here in Chapter 4, she, too, takes up the theme of starvation and in her actions carries forth what has been typical thus far–the cynical theme of adults versus children, especially ‘parish’ children, or, rather, children she would just as soon watch perish; her verbal and physical abuse is symbolic of the latter:

‘”Ah! I dare say he will,” replied the lady pettishly, “on our victuals and our drink. I see no saving in parish children, not I; for they always cost more to keep, than they’re worth…”‘”

~Lenny H.

And Lenny continues the theme of darkness and entrapment:

Lenny H. comments (above)

I respond to the entrapment issue, with an emphasis on the light/dark contrast which has been part of our ongoing conversation:

Rach M. comments (above)

Lenny responds:

Lenny H. comments (above)

“A Reproach to the System”: The Criminality of Lawbreaking vs. the Criminality of/within the Law

I just want to emphasize again Lenny’s final comment from the above passage, under a heading that will perhaps come ’round again and again:

“And, I feel, that underpinning both ‘methods’ of crime is the ever present theme of GREED. Ironically, money can be made from the baby farm and workhouse just as fully but maybe more subtly than the more obvious methods of crime involving the stealing of handkerchiefs and wallets. In this way, the novel presents two, greed motivated, ‘SYSTEMS’ or ‘INDUSTRIES’ that kill, maim and fleece the British society of this time in the late 1830’s.”

~Lenny H.

And Chris and I have a little dialogue here in response to Lenny’s comment:

Finally, Steve has a question to leave us with: Did those Dickens wrote about recognize themselves in this judgement?

A Look-ahead to Week Two of Oliver Twist (19-25 April)

This week we’ll be reading Chapters 12-22, which constitute the monthly numbers VI-X, published in Aug, Sept, Nov, and Dec 1837, and Jan of 1838.

You can read the text in full at The Circumlocution Office if you prefer the online format or don’t have a copy. There are also a number of places (including Gutenberg) where it can be downloaded for free.

It’s interesting the discussion thus far has focused so much on the dark and depressing aspects of the book. Not that it isn’t dark and depressing, but when I read it, I’m always struck by how fun and engaging it is, notwithstanding, with Dickens’s elaborately sarcastic prose. I guess it makes sense that readers would be struck by the darkness and social commentary since they’re covering it right after The Pickwick Papers, in which darkness was mostly confined to the stories within the story and there was minimal social commentary. Well, minimal by Dickens’s standards. It arguably had more than you’d expect from a sitcom. (I think a sitcom is a good modern equivalent of The Pickwick Papers.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’ve hit on one of Dickens’s greatest tools – his ability to make us laugh at things that, on their face, we probably should laugh at but, if we are honest, we can’t help but laugh at.

James R. Kincaid wrote a book called “Dickens and the Rhetoric of Laughter” (1971). His chapter on “Oliver Twist” is called “‘Oliver Twist’: Laughter and the Rhetoric of Attach”. It says, in part:

“One of the major questions, then, is how such a dark novel can be so funny. It is probable that most critics often laugh while reading it; it is certain that when they are finished they write essays on its bleak effects. And they are right – in both caases. The reason for the paradoxical reaction is, I think, that Dickens uses laughter here to subvert our conventional reactions and to emphasize more dramatically the isolation of his young hero, indeed, the essential isolation of all men. In denying the possibility of a comic society and yet provoking laughter, the novel continually thwarts and frustrates the reader; for our laughter continues to search for a social basis, even when there is no longer any support for it in the novel. In other words, laughter is stirred, but the impulses aroused behind it are not allowed to collect and settle. Unlike the convivial atmosphere of “Pickwick Papers”, where out laughter finally provides us a place with Sam and with Mr. Pickwick, here there is no possibility of escape to a society sanctified by the expulsion of villains. Instead, laughter is used primarily as a weapon, to suggest that we are the villains. The selfishness and unfeeling cruelty which are a subconscious part of much laughter are here brought to the surface and used to intensify our reaction and our involvement. Laughter is a necessary part of the proper reaction to the novel, but in the end it is used against us, undercutting the comfortable aloofness we had originally maintained and forcing us into conjunction with the lonely and terrified orphan. This suggests that, just as in “Pickwick”, the basic attack is on detachment. But the comparison doesn’t go very far. There are no comparable rewards for submitting to the attack in “Oliver Twist” and no comfortably stable scheme of values to which we can attach ourselves. We are left alone in a rootless and threatening world.” (51-52)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Whoops – I meant to say “You’ve hit on one of Dickens’s greatest tools – his ability to make us laugh at things that, on their face, we probably SHOULDN’T laugh at but, if we are honest, we can’t help but laugh at.” (changes things a bit)

LikeLike

Dear Inimitables,

Such a rich tapestry of thought, commentary, insight, and heart-felt reaction to the bleakness of the world that Oliver was born in to.

Our brilliant angry young author is surely posing the question that Chris raises: not so much what is our duty to each other but rather how did we forget that duty?

The moral conscience in Dickens is fierce and incisive. It reminds me of the adage about comforting the distressed and discomforting the comfortable.

There is so much in the commentary to thank you all for: parish children who the greed-riddled adults wish would perish; “despised by all, and pitied by none”–a haunting, reverberating line; people being shaped by their occupations/professions; the hope that the novel will move towards more light and freedom, balancing the nearly impenetrable darkness of the early chapters.

Our son, Luke, has often observed that we live in a Greed Economy. Methinks the same epithet could easily apply to Dickens’ time.

Let’s sally forth, hoping against hope for some joy, light, and comfort in Oliver’s life!!!

Daniel

LikeLiked by 1 person

Towards the end of Pickwick Papers I started compiling a list of all the narrative techniques I had noticed Dickens using in the book to heighten the drama and sustain reader engagement:

• give your minor characters a single distinct quirk or obsession, then bring those characters together and have them interact in hilarious ways

• break up the narrative with minor acts of violence or mayhem

• place your characters on the go, so that the novel has the illusion of movement

• intersperse moments of sadness or drama with humorous antics

• make your protagonists sympathetic by making them lonely, misunderstood, downtrodden

• allow dialogue to comprise the majority of each chapter

• personify the natural world! compare things to animals!

• end chapters on a cliffhanger or a note of irresolution

Although at this point he was, as the Stationmaster noted, writing the Victorian equivalent of a sitcom, he had already begun to master the command of narrative that he would employ to even greater effect in his later books, including Oliver. Although he had shifted tones and genres entirely, the lessons he had learned in Pickwick held him in good stead. Re-reading Oliver Twist a few years ago, I was struck by this delightfully shameless cliffhanger at the end of the second chapter, when the gentleman in the white waistcoat remarks that Oliver is likely to end up at the wrong end of a noose. And then Dickens adds, “As I purpose to show in the sequel whether the white-waistcoated gentleman was right or not, I should perhaps mar the interest of this narrative … if I ventured to hint just yet, whether the life of Oliver Twist had this violent termination or no” – as calculated an appeal to keep the reader reading as there’s ever been. And he keeps doing it in the chapters to come! It’s cheap, mercenary, masterful. We have to remember that Dickens was writing for fame and money, and he knew how to get both.

As I was typing up Philip Pullman’s essay on Oliver Twist this weekend, I was struck by his assertion that Dickens was writing for a medium that didn’t exist yet, the cinema. (I quibble with this in that I think today he would be writing for television, but the larger point stands.) He says Dickens was unknowingly inventing the language of film with his descriptions that feel like stage directions. What’s more, he was a master of the close-up, of taking a big, dramatic scene and zooming in on a single suggestive detail. Pullman writes, “As well as illuminating the broad melodrama of the big effects, that incandescent energy of Dickens also shows up in the tiny details of behavior, the little incidents that he seems to find at the tip of his goose-quill, that spring into being the moment he writes them down,” and lists several examples from Oliver, including the moment early in the novel when Mr Bumble “absently and automatically” boxes a boy’s ears. He says these moments must have occurred to Dickens in the heat of writing; they seem to spring off the page as if they were only just being envisioned. And I love those little eccentricities of character that are continually imposing themselves on the story, that Dickens is so good at, and I think reading this essay years ago and learning to see these character beats in Dickens really ruined blockbuster filmmaking for me, because whenever I watch a movie now I’m sitting there going “okay but where are the weird, offbeat character moments?” They are, or ought to be, the bread-and-butter of storytelling.

Right, off to file my taxes before midnight…

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a Masterclass, isn’t it, Boze? Love to say more now, but I’m in the same situation…taxes! 😜

Dickens always comes first, & so happy I’m not the only one who thinks so 😅😁

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s true that Dickens uses a lot of action scenes that are more ideal for movies/television, but I still believe books were the ideal medium for him. In a movie or a television show, you’d lose all the great little narrator asides like this.

“The liberality of Mrs. Sowerberry to Oliver, had consisted of a profuse bestowal upon him of all the dirty odds and ends which nobody else would eat; so there was a great deal of meekness and self-devotion in her voluntarily remaining under Mr. Bumble’s heavy accusation” (that she had given Oliver too much food). “Of which, to do her justice, she was wholly innocent, in thought, word, or deed.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s not to say I think you or Pullman are totally wrong, just that I don’t think you’re totally right. For more on the specifically literary virtues of Dickens, I recommend The Artful Dickens: The Tricks and Ploys of the Great Novelist by John Mullan.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love The Artful Dickens!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I loved the Pullman essay, and I think it’d be a fantastic share here…with, as you said elsewhere, Boze, a spoiler alert! I won’t say anything here that includes spoilers. I loved his emphasis on Dickens’ preternatural ***energy***! That always strikes one forcibly on reading it; as Pullman emphasizes, he *did* more closely plot his novels ahead of time later in his career, but this early on, we have that wild and whirling feeling like Dickens is on the same ride we are…hardly knowing what’s around the bend; he’s telling us what he *sees*, as he sees it. And besides the connection to the cinema, Boze, I loved Pullman’s emphasis on Dickens and the theatre…a subject that I feel like I keep getting drawn back into. And here, it is connected to the light/dark themes, the grand melodrama of the “horror” in Oliver:

“Throughout his life, Dickens was powerfully attracted to the theatre. His involvement with amateur theatricals, his close association with professional actors, and not least his own public readings, which were powerfully dramatic—all testify to his great love of the stage. What matters here is the effect that passionate interest had on the way he told stories on the page. Again and again he comes up with scenes and characters whose brilliance and force (or, to be sure, whose exaggeration and sheer noise) seem to demand darkness and limelight, a proscenium, an auditorium, an audience, in order to achieve their full effects.

“It’s partly a matter of space and scale: in order to be seen clearly from a distance, effects have to be broad enough to seem coarse when close to. This, I’m sure, is part of the source of Dickens’s particular melodramatic quality. His story was occupying a mental space that demanded vivid light and profound darkness and loud volume in order for the events and the characters to be perfectly clear to the furthest occupant of the highest seat in the gods, and that colossal energy of his was equal to the task. “

LikeLiked by 1 person

Especially for those who aren’t reading the Ackroyd piece that Chris shared (due to the spoilers), I thought I’d just copy out this passage which I thought was a really fascinating and unique take on it (which comes at the conclusion of a marvelous passage on the importance of the death of Mary Hogarth and its effect too on his writing of Oliver):

“…his whole conception of Oliver Twist seems to have changed. He recreated Rose Maylie in the image of his dead sister-in-law, of course, but even before that happy resurrection much of the topical and polemical intent of the novel is abandoned and Dickens introduces a slower, more melancholy note which comes to pervade most of its subsequent pages. In fact it can be said that Dickens now introduces something of English Romantic poetry—Wordsworthian, in particular—into his fiction, and it has often been claimed that it is precisely this new presence which marks the true distinction of Oliver Twist. Dickens brings into his novel ideas of innate beauty, of childhood innocence, of some previous state of blessedness from which we come and to which we may eventually return. It is in these passages that his prose seems instinctively to move with poetic cadence and diction. It is as if the death of Mary Hogarth had broken him open, and the real music of his being had been released—and how powerful it becomes when it is aligned both with his helpless memories of his own childhood and with the greatest extant tradition in English poetry.”

LikeLike

April 19-25/22 – Week Two – Chapters 12-22

Oliver lives on a kind of inverse rollercoaster that has very few and shallow ups but many degrees of down. This poor kid can’t catch a break! He’s never given a chance to show his quality – he is good, kind, gentle, caring, innocent – because he’s seen either as an encumbrance or a tool. His one chance to prove himself, at Mr Brownlow’s, is snatched away by the same gang whose attempt to corrupt him threw him in Mr Brownlow’s way in the first place.

Oliver is, unsurprisingly, passive in the face of his tormentors. He is, after all, a child and we are seeing the world through his eyes. The few times he does show spirit by speaking up for himself or lashing out result in his being quickly, and quite literally, knocked back down and put back in his place (usually a coal cellar or other confined space). But these reprimands do not corrupt him. He recoils from the bad influences, even though he might be momentarily amused by the antics of Fagin and the boys, and patently rejects the criminal lifestyle being modeled before him. Yet in this horrible environment he finds he has a protector – Nancy.

At first Nancy sees Oliver as just another boy brought into Fagin’s den, and she has no qualms about locating him after the pickpocketing debacle or in waylaying him on his book return errand. But as she and Bill, with Oliver held fast between them, pass Newgate prison and the church bells toll bringing forth images of the men on death row, Nancy begins to hesitate. She senses, as they pass Newgate, that Bill’s days are numbered and for her losing him would be awful – “I wouldn’t hurry by, if it was you that was coming out to be hung the next time eight o’clock struck, Bill. I’d walk round and round the place till I dropped, if the snow was on the ground, and I hadn’t a shawl to cover me.” She also realizes that this is the fate SHE has now secured for Oliver. She knew the risk Oliver’s escape posed to the gang which, I think, is the reason she worked to get him back, but her emotional experience at Newgate triggers a change in her.

In all her years with the gang Nancy has, no doubt, seen many boys, and girls, come through the system. None affected her – until Oliver. This odd boy, scared and innocent, coupled with her recent empathy for the men in Newgate, throws the horror of the gang lifestyle, her lifestyle, into bold relief – “I thieved for you when I was a child not half as old as this (pointing to Oliver). I have been in the same trade, and in the same service, for twelve years since”. She is a prostitute, had no doubt been a child prostitute, she’s also a battered woman and the victim of predatory, decidedly older, men – of her clients generally but of Fagin and Bill most particularly. Fagin, the one who “recruited” her, is initially described as a “very old” man, and Bill, her “boyfriend” who keeps her in line, is “a stoutly-built fellow of about five-and-forty”. Compare this to Nancy’s age, clarified in a footnote in my text: “If Nancy came under Fagin’s influence when she was half Oliver’s age, say five years old, and since she has been at it for twelve years, she is therefore seventeen years old.”

She’s a teenager, rising to adulthood, who becomes suddenly aware! She knows her life is crap – “It is my living, and the cold, wet, dirty streets are my home” – but instinctively she “springs” to action to protect Oliver, first from the dog and then from Fagin and Bill. In Oliver she sees her own young self who had no champion – “I wish I had been struck dead in the street, or changed places with them we passed so near to-night, before I had lent a hand in bringing him here. He’s a thief, a liar, a devil, all that’s bad, from this night forth; isn’t that enough for the old wretch without blows?” Oliver’s presence unleashes the mama bear in her which Fagin and Bill subdue only with great difficulty and which they, in future, aim to avoid – “There is something about a roused woman, especially if she add to all her other strong passions the fierce impulses of recklessness and despair, which few men like to provoke.”

But she knows too well that Oliver will have no peace within the gang unless and until he is a full-fledged member, until his own neck is truly in the noose. This is why she puts Oliver’s name forth as the boy to be used in the robbery, why she vouches for his performance, and why she is the one to prepare him for his task. It is also why, when she comes to collect Oliver, she has a panic attack – “‘God forgive me! . . . I never thought of all this.’ She rocked herself to and fro, and then, wringing her hands violently, caught her throat, and, uttering a gurgling sound, struggled and gasped for breath. . . . The girl burst into a fit of loud laughter, beating her hands upon her knees, and her feet upon the ground, meanwhile; and, suddenly stopping, drew her shawl close around her, and shivered with cold.” But she gets a hold of herself and prepares Oliver for what’s ahead, cautioning him and reassuring him in turns, and finishing her tutorial by explaining what it has cost her to intervene on his behalf – “‘You are hedged round and round; and, if ever you are to get loose from here, this is not the time. . . . I have saved you from being ill-used once, and I will again, and I do now . . . I have promised for your being quiet and silent; if you are not, you will only do harm to yourself and me too, and perhaps be my death.’ . . . She pointed hastily to some livid bruises upon her neck and arms and continued with great rapidity. ‘Remember this, and don’t let me suffer more for you just now. If I could help you I would, but I have not the power: they don’t mean to harm you; and whatever they make you do, is no fault of yours. Hush! Every word from you is a blow for me: give me your hand – make haste, your hand!’” And so Oliver is delivered to Bill. And Nancy, barely able to look at Oliver, can only brood before the fire.

How far will Nancy go to protect Oliver? Is it even really Oliver she is protecting? Or is she motivated by something – someone – else?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Nancy might be my favorite character in the book. Thackeray was probably right when he said that she was “no more like a thief’s mistress than one of Gesner’s shepherdesses resembles a real country wench.” But I don’t care. I love a good unrealistic character!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Extraordinary analysis, Chris. Nancy’s caught between the light and dark worlds–as we’ve been calling them throughout our discussion of Dickens, starting with the SKETCHES. And you do such a good job of pointing this out. Oliver in his goodness and innocent youth, obviously stands for the lighter end of the spectrum–should he not be completely and irrevocably drawn into the Fagin/Sykes milieu as the other boys have experienced. They, unfortunately, have been swallowed by their dark demonic shadows–as represented by the archetypes of Fagin and Sikes. Nancy’s “child within”–a part of her shadow that is activated by Oliver, begins to assert itself early; and you point this out so succinctly:

“But she gets a hold of herself and prepares Oliver for what’s ahead, cautioning him and reassuring him in turns, and finishing her tutorial by explaining what it has cost her to intervene on his behalf – “‘You are hedged round and round; and, if ever you are to get loose from here, this is not the time. . . . I have saved you from being ill-used once, and I will again, and I do now . . ..”

In many ways, this segment of the novel is among its most beautiful– and promising–as it shows the possibility for Nancy’s (and society’s?) redemption, after the darkness that has overtaken her life. In fact two things simultaneously are happening, here. In Jungian terms, Oliver has “activated” the CHILD ARCHETYPE that has remained dormant within Nancy’s psyche, and brings it productively into consciousness where it can declare itself to Oliver as its savior and to suggest to Oliver that he is worth saving. And her new attitude to Oliver indicates that she ready to move HER psyche to some kind of completion. Thus, She, with Oliver’s “help” is slowly becoming more “complete” psychically. In short, the “child” in her comes (forces its way) out of her shadow in what Jungians would call a compensatory factor. With Oliver’s help, she recognizes the value of the child, and, likewise, will come to rue the very fact that she “lost” her “child” somewhere along the way. Now, she’s in the “recovery” mode.

At the same time. Nancy operates as a positive ANIMA figure to Oliver, and allows him to “live” (now) and perhaps to thrive “healthily” throughout his life as the novel progresses. In other words, she activates HIS anima and gives him hope and the desire to care, positively, for the welfare of others–especially women: to not see them as dark figures to be used and abused. And, as we soon find out, there are other anima figures who “come to light “and also–in more earnest– help to rescue him from the gang of shadows which threaten to annihilate his psyche in the course of our first two segments of reading. She, and others, then, activate the anima within him, and will help him psychically to become NOT a Fagin or Sikes, but more like the character of Mr. Brownlow, whose ANIMA IS ALIVE AND WELL!

In fact, ANIMA “activation” or its LACK is also one of the main themes in this novel, and comes within the context of a society at large–as we see from the novel’s beginning–that is sorely lacking in Anima expression or, in other words– the goodness, care and sensitivity represented by the positive anima. Most of the male characters in the early stages of the novel have suppressed their ANIMA figures (along with the CHILD), and, as such, these archetypes lie dormant within their respective shadows; they have little use for any positive caring, feeling, loving, sensitivity toward children or women (or, even, people at large!). Their psyches are crippled and totally ossified by this neglect of these latent and neglected key elements of their mental structures. They’ve been, in a sense, “swallowed by” the negative aspects of their shadows! We could say that these dark, mostly evil characters are personifications of what Dickens perceives as a mental sickness in his British society. To extend this idea out further and to give it more context, we could say that the German populace before and during WWII were “swallowed’ by the NEGATIVE ASPECTS OF Hitler’s SHADOW. This dark tendency I feel, is what Dickens is exposing in and to the people of England in the 1830’s.

Thus, Nancy and Oliver come, along with the other “positive” characters in the novel, to offer a glimmer of hope in a novel that is, otherwise, driven by and surrounded by darker, evil forces.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, Chris. I just read your last short paragraph and want to give a timely response to your question. I believe, in the entire context of Nancy’s psyche and her psychic health, that by summoning (up) and protecting Oliver (as archetype and person), she is beginning to protect and “save” a part of her OWN “self,” the child segment that, before she comes into the novel , she’s “split off” and buried within her unconscious. With her “relationship” with Oliver, she is (her psyche is…)gradually trying to retrieve that aspect from her shadow and bring it back into her conscious mind and value it for what it represents–innocence, goodness, grace, playfulness, etc. Among other things, her motivation has to do with SELF-preservation as well as the preservation of Oliver. There is an interesting simultaneity here! Interior as well as exterior….

LikeLiked by 2 people

It is so interesting how, in Dickens, moments of real light and beauty are often equated with Rest. I feel like this will keep coming around again…

Here at the beginning of the week’s reads, we have Oliver finally able to have some respite from a life which was always hurried along both within and without the system, as though he were a cog in the great societal Machine. Just as Dickens himself was hurried along in childhood to live and make his way as though he were a small adult, fending for himself; to hurry into adulthood, to hurry into work, deadlines, responsibilities, and keep the Machine moving. Like Pancks in Little Dorrit…“fag and grind…turn the wheel…what else are we made for?” Anyway, to that effect. (Chris had earlier alluded to Jo in Bleak House, being hurried along…move along! And I’m asking: to…where? I don’t know—so long as he is moved along, and we as a society don’t have to be bothered with these human beings who are living reproaches to us. Unless they serve the immense pecuniary Mangle of society—I think that is the phrase from A Tale of Two Cities.) There is a kind of frenetic pacing, as frenetic as Dickens’ superhumanly-energetic self, to the story; the kind of adrenaline that kicks in when one is just in survival mode; the pacing of Oliver’s progress from one point in the novel to another. The Mangle won’t stop squeezing, the Machine won’t quit moving.

Now, however, at the opening of Chapter 12, Oliver is cared for as though he actually matters for his own sake—he can stop, and rest—and it is a novelty.

Bringing it back to Nancy: I loved Chris and Lenny’s analyses here. Oliver is awakening something dormant within her; always there, always constantly put down by her surroundings, the light squelched and buried. In the most recent Dickens biography that I’ve read, Claire Tomalin ~ I never think of Peter Ackroyd’s as my most recent, even though I go back to him most constantly, consulting him like a friend ~ Tomalin has an entire passage on why Nancy is the failure of Oliver Twist ~ the element that doesn’t work, the stagy-melodramatic element that makes her gestures too big and too unrealistic. “He fails,” she writes, “because he makes her behave like an actress in a bad play” (98). I’m curious how it’ll all strike me on this reread, but my sense is that I totally disagree with Tomalin’s assessment. Dickens insisted he knew this woman ~ this kind of soul ~ in real life, and was to help many such women after, and I wouldn’t be surprised.

Frankly, when one is constantly living under the shadow, everything decent and beautiful and restful constantly threatening to be squeezed out of you in society’s great Mangle, I think one is bound to act and express oneself in ways that are something larger than life. Ackroyd brought up (not in this context) that those suffering mental illness were attracted to Dickens, would write him constantly, and there is a reason: the “strangeness of his imagination” (to paraphrase Ackroyd) that speaks to the strangeness in all of us, and in society. And there is a kind of madness ~ and certainly, illness ~ to the kind of life that Nancy has been living.

But in combination with that sense ~that hers is a realistic progression, to me ~ I’m going back to Ackroyd’s sense of the Romantic, poetic bent of this novel. Ackroyd writes: “There is a poetry in this novel which is quite unlike anything which is to be seen in previous fiction, a poetry of barely whispered notes that sets up a deep refrain within the text, for it was Dickens’s great achievement to bring the language of the ‘Romantic’ period into the area of prose narrative” (231).

Although Oliver is not among my favorite Dickens novels, there is a way in which the same criticism that can be leveled against, say, A Tale of Two Cities, can also be brought up here. The larger-than-life quality, the grandeur and theatricality of it. But if we try to look at it like something of a parable, something so big that it calls for nothing less than the big gesture, the striking image, the Shadow and the Light. It just…works.

Nancy is beginning to *see* the light she was afraid of when she came to encounter Oliver, and to *hear*:

“They had hurried on a few paces, when a deep church-bell struck the hour. With its first stroke, his two conductors stopped, and turned their heads in the direction whence the sound proceeded.

“‘Eight o’ clock, Bill,’ said Nancy, when the bell ceased.

“‘What’s the good of telling me that; I can hear it, can’t I!’ replied Sikes.

“‘I wonder whether THEY can hear it,’ said Nancy.”

She is beginning to think of something larger, beyond the confined space that she’s been living in, and to think of the *other*.

LikeLike

Here is the crucial segment in Chapter 20 that the three of us have been discussing and analyzing. It’s the centerpiece of the growing dynamic between Oliver and Nancy and reflects wholly the various ideas that Chris, Rach and I have been talking about. Chris nails it so beautifully when she discusses the “anxiety attack” that Nancy is having (Lord knows, I’ve had enough panic attacks to fill a hospital waiting room several times!). Her confusion and soul-searching is made so palpable by the gestures and turns of speech that Dickens gives her. I’ve been there; I know this stuff. The sense of something happening practically out of nowhere, the feeling of suffocation, the gasping of breath, the agonizing gestures–all this seems so real!

But what is also noteworthy is Oliver’s intense caring for her. He’s got to be confused, too, and is attempting to give her some kind of solace, it seems to me, more adult than childlike. In some ways, I feel that they stimulate within each other a very interesting “progression” in their personalities. She’s become, in an apparent way, almost childlike, where he assumes more the role of an adult. There is some terror here and Oliver, stirs the fire, perhaps to gain time, hoping that Nancy can compose herself enough to relate to him what is going through her troubled mind. The visuals, the dialogue, the tension–all so well dramatized by our author.

There are several moments in this encounter that we’ve already discussed as being important, but I’m again and again drawn to this brief glimpse of Oliver’s thought: “Oliver could see that he had some power over the girl’s better feelings….”

There, the shoe has dropped, and our hero recognizes the compatibility the two of them share. For him, feeling this moment operates as an epiphany, a kind of ray of hope that his life might be more hopeful than he’s thought. And Nancy, also, has a similar moment of recognition that he has connected with her desire to save him, and cautions him to “Hush.”

This is the quote from Chapter 20 that we are referring to:

“She rocked herself to and fro; caught her throat; and, uttering a gurgling sound, gasped for breath.

‘Nancy!’ cried Oliver, ‘What is it?’

The girl beat her hands upon her knees, and her feet upon the ground; and, suddenly stopping, drew her shawl close round her: and shivered with cold.

Oliver stirred the fire. Drawing her chair close to it, she sat there, for a little time, without speaking; but at length she raised her head, and looked round.

‘I don’t know what comes over me sometimes,’ said she, affecting to busy herself in arranging her dress; ‘it’s this damp dirty room, I think. Now, Nolly, dear, are you ready?’

‘Am I to go with you?’ asked Oliver.

‘Yes. I have come from Bill,’ replied the girl. ‘You are to go with me.’

‘What for?’ asked Oliver, recoiling.

‘What for?’ echoed the girl, raising her eyes, and averting them again, the moment they encountered the boy’s face. ‘Oh! For no harm.’

‘I don’t believe it,’ said Oliver: who had watched her closely.

‘Have it your own way,’ rejoined the girl, affecting to laugh. ‘For no good, then.’

Oliver could see that he had some power over the girl’s better feelings, and, for an instant, thought of appealing to her compassion for his helpless state. But, then, the thought darted across his mind that it was barely eleven o’clock; and that many people were still in the streets: of whom surely some might be found to give credence to his tale. As the reflection occured to him, he stepped forward: and said, somewhat hastily, that he was ready.

Neither his brief consideration, nor its purport, was lost on his companion. She eyed him narrowly, while he spoke; and cast upon him a look of intelligence which sufficiently showed that she guessed what had been passing in his thoughts.

‘Hush!’ said the girl, stooping over him, and pointing to the door as she looked cautiously round. ‘You can’t help yourself. I have tried hard for you, but all to no purpose. You are hedged round and round. If ever you are to get loose from here, this is not the time.’

Struck by the energy of her manner, Oliver looked up in her face with great surprise. She seemed to speak the truth; her countenance was white and agitated; and she trembled with very earnestness.

‘I have saved you from being ill-used once, and I will again, and I do now,’ continued the girl aloud; ‘for those who would have fetched you, if I had not, would have been far more rough than me. I have promised for your being quiet and silent; if you are not, you will only do harm to yourself and me too, and perhaps be my death. See here! I have borne all this for you already, as true as God sees me show it.’”

Rach talks about Tomlin’s view of this growing relationship between Oliver and Nancy; Tomlin apparently senses something artificial and overly dramatic in this sequence. This makes me wonder to what is she referring and to what extent she’s spent time doing a close reading of this key moment in the novel. If she had, I believe she’s revise her complaint and realize that this is THE FULCRUM around which the rest of the novel will turn. As I brought forth in my analysis, the two archetypes have been fully activated in this momentous meeting between these two “children” and will mark out much of the way the rest of the novel falls together. I can’t help but think of Wordsworth’s pronouncement–“the child is father to the man.” In this case in OLIVER, that phrase really rings true for me.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I thought I’d provide a wider context for the Wordsworth passage as it pertains to TWIST by quoting the poem in full and then including a brief comment about the poem and its meaning by a critic who gives a more elaborate reading of the poem–explaining its psychological importance ; his comments fit nicely into our discussion about Oliver and Nancy in Chapter 20:

“By Simran Khurana

Updated on August 13, 2019

William Wordsworth used the expression, “The child is the father of the man” in his famous 1802 poem, “My Heart Leaps Up,” also known as “The Rainbow.” This quote has made its way into popular culture. What does it mean?

My Heart Leaps Up

My heart leaps up when I behold

A rainbow in the sky:

So was it when my life began;

So is it now I am a man;

So be it when I shall grow old,

Or let me die!

The Child is father of the Man;

And I could wish my days to be

Bound each to each by natural piety.

Wordsworth uses the expression in a very positive sense, noting that seeing a rainbow produced awe and joy when he was a child, and he still felt those emotions as a grown man. He hopes that these emotions will continue throughout his life, that he will retain that pure joy of youth. He also laments that he would rather die than lose that leap of the heart and youthful enthusiasm.

Also, note that Wordsworth was a lover of geometry, and the use of “piety” in the last line is a play on the number pi. In the story of Noah in the Bible, the rainbow was given by God as a sign of God’s promise that He would not again destroy the entire earth in a flood. It is the mark of a continuing covenant. That is signaled in the poem by the word “bound.”

Modern Use of “The Child Is Father of the Man”

While Wordsworth used the phrase to express hope that he would retain the joys of youth, we often see this expression used to imply the establishment of both positive and negative traits in youth. In watching children at play, we notice that they demonstrate certain characteristics which may remain with them into adulthood.

One interpretation—the “nurture” viewpoint—is that it is necessary to instill in children healthy attitudes and positive traits so they grow up to become balanced individuals. However, the “nature” viewpoint notes that children may be born with certain traits, as can be seen in studies of identical twins who were separated at birth. Different traits, attitudes, and experiences are influenced in different ways by both nature and nurture.

Certainly, traumatic life experiences in youth inevitably occur which also influence us throughout life. Lessons learned both in positive and negative ways guide us all into adulthood, for better or worse.”

LikeLiked by 2 people

The end of chapter 14 is, for me, the best cliffhanger yet…the image of Brownlow and Grimwig sitting in the gathering gloom, waiting for an Oliver who WE know wouldn’t do a runner and must have met some awful fate, means it must have been an awfully long wait for the public for the next part!

Chapter 20 has been fully (and wonderfully) dissected elsewhere, so I want to concentrate this week on chapter 17. Young mournful Dick’s melodrama is extreme by modern standards (“‘and I should like to tell him’ said the child, pressing his small hands together, and speaking with great fervour, ‘that I was glad to die when I was very young; for, perhaps, if I had lived to be a man and grown old, my little sister who is in Heaven, might forget me, or be unlike me; and it would be so much happier if we were children there together’”) As child melodrama goes, we ain’t seen nothing yet – I’m looking at you, Curiosity Shop! – but Dickens already was becoming adept at pulling heart strings and going straight for the jugular every time.

Now, Bumble and Mrs Mann are portrayed here as truly evil – Sikes, Fagin etc. at least have greed and circumstance as factors in their evilness, while Bumble and Mann are ‘just’ doing their jobs. That they do them abominably cruelly where it is in their power to be kinder, makes them the worst sort of monsters.

LikeLiked by 3 people