Wherein your co-hosts of The Dickens Chronological Reading Club 2022-24 (#DickensClub) wrap up weeks three and four of our twenty-fourth read, Our Mutual Friend; with a chapter summary and discussion wrap-up.

By the members of the #DickensClub, edited/compiled by Rach

Friends, what revelations we’ve had this week, especially in regard to John Harmon! And fresh conspiracies, too. What are Wegg and Venus up to, and will they succeed? Are Harmon’s hopes for Bella’s love forever dashed? What are we to make of the reckless–and sometimes downright unlikeable–Eugene Wrayburn? Will he be the victim of Headstone’s violence?

And what on earth will Lizzie do about these men in her life?

So much to discuss; but first, a few quick links:

- General Mems

- Our Mutual Friend, “Book the Second”: A Summary

- Discussion Wrap-Up (Weeks 3-4)

- A Look-Ahead to Weeks 5 & 6 of Our Mutual Friend (25 June to 8 July, 2024)

General Mems

Huge THANK YOU to our member Chris for posting a supplement to the introduction!

SAVE THE DATE (and let us know which works for you)! For our Zoom chat on Our Mutual Friend, we’re looking at either Sat, Aug 10 or Sat, Aug 17th, 2024.

If you’re counting, today is Day 903 (and week 130) in our #DickensClub! This week and next, we’ll be reading “Book the Third: A Long Lane,” Chapters 1-17, of Our Mutual Friend, our twenty-fourth read as the group. Please feel free to comment below this post for the fifth and sixth weeks’ chapters or use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter.

For our introduction to this marvelous novel, and our eight-week reading schedule, please click here. For Chris’ supplementary materials for Our Mutual Friend, please click here.

No matter where you’re at in the reading process, a huge “thank you” for reading along with us. Heartfelt thanks to our dear Dickens Fellowship, The Dickens Society, and the Charles Dickens Letters Project for retweets, and to all those liking, sharing, and encouraging our Club, including Gina Dalfonzo, Dr. Christian Lehmann and Dr. Pete Orford. Huge “thank you” also to The Circumlocution Office (on twitter also!) for providing such a marvellous online resource for us. And for any more recent members or for those who might be interested in joining: the revised two-and-a-half year reading schedule can be found here. If you’ve been reading along with us but aren’t yet on the Member List, we would love to add you! Please feel free to message Rach here on the site, or on twitter.

Our Mutual Friend, “Book the Second”: A Summary

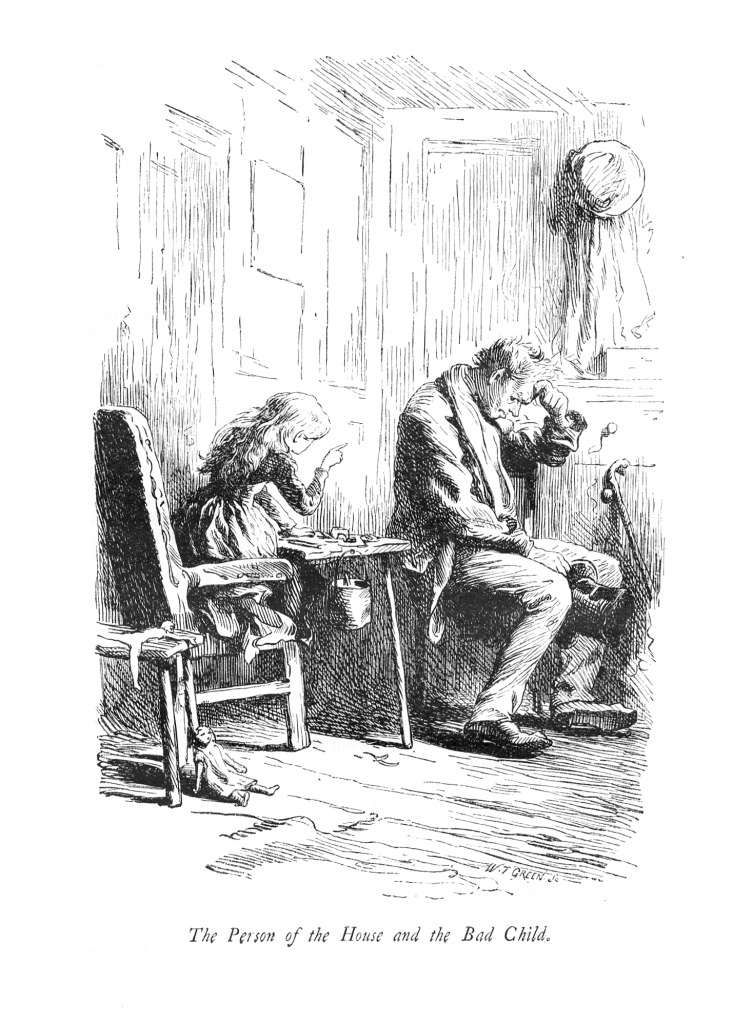

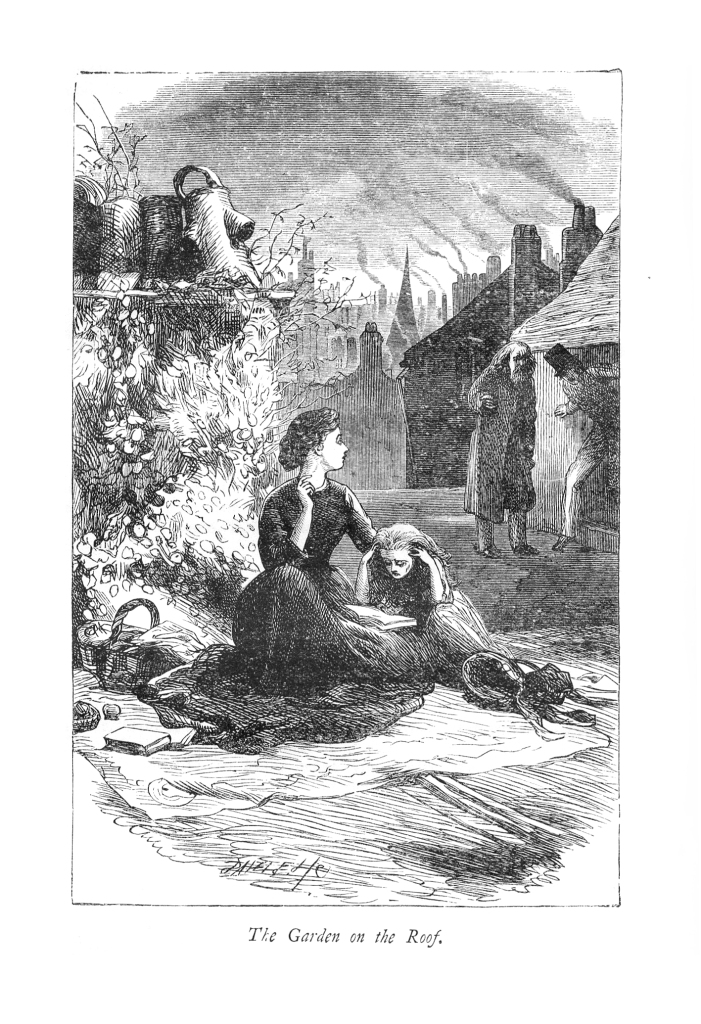

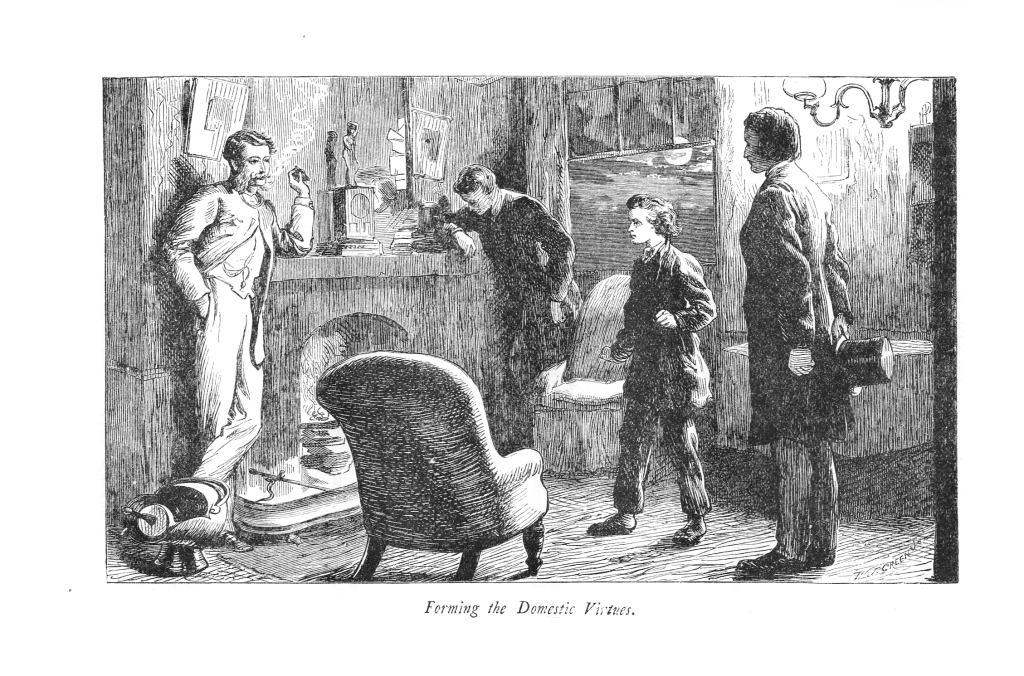

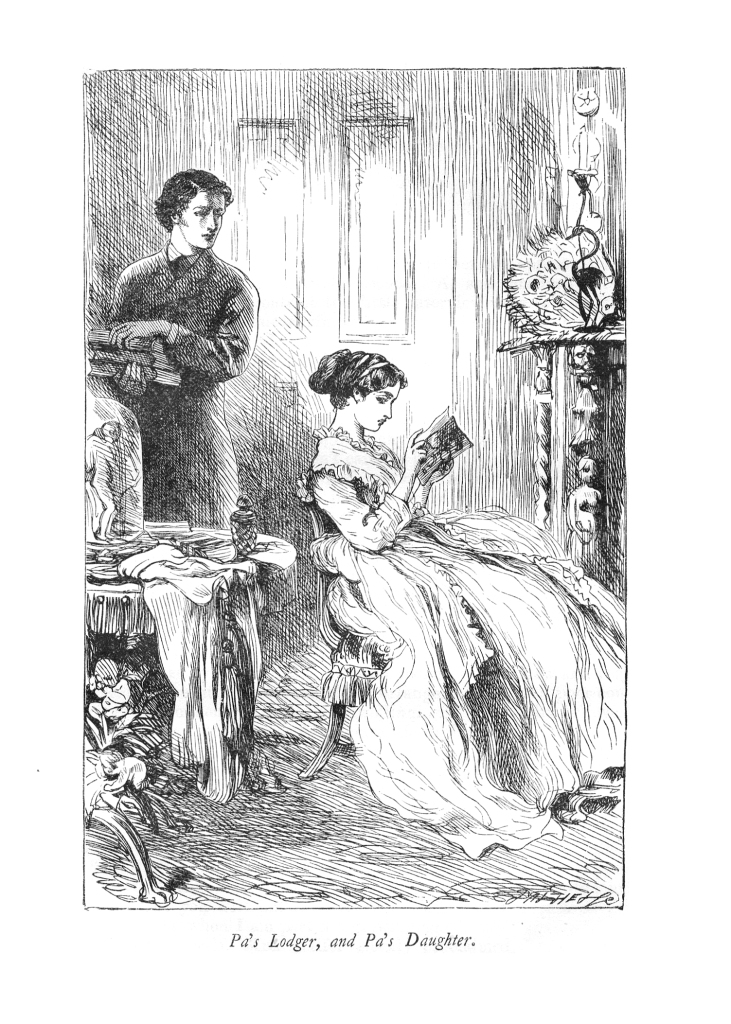

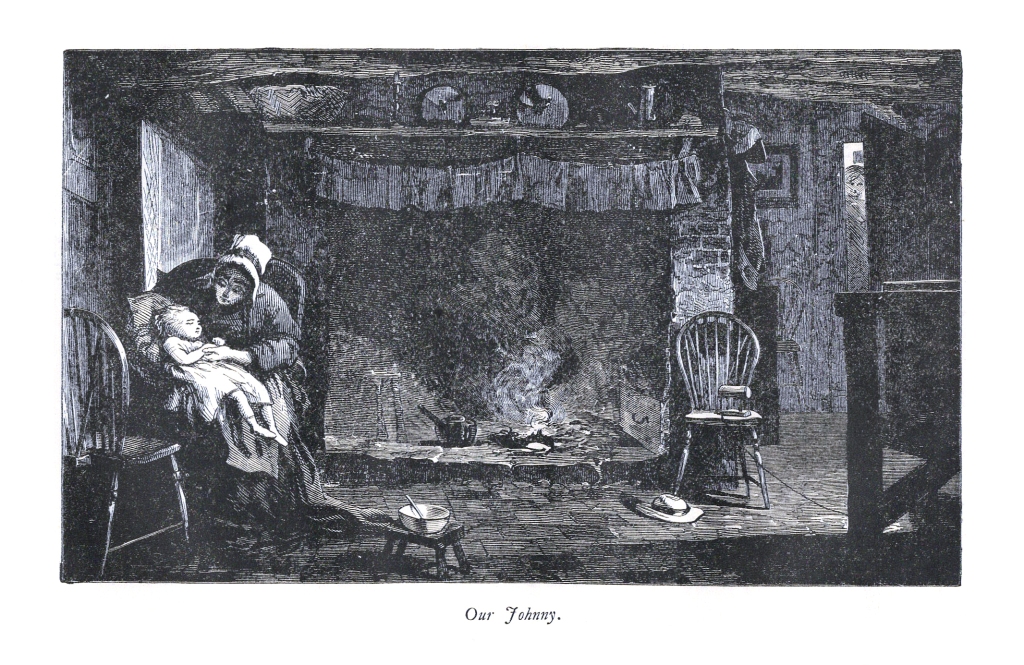

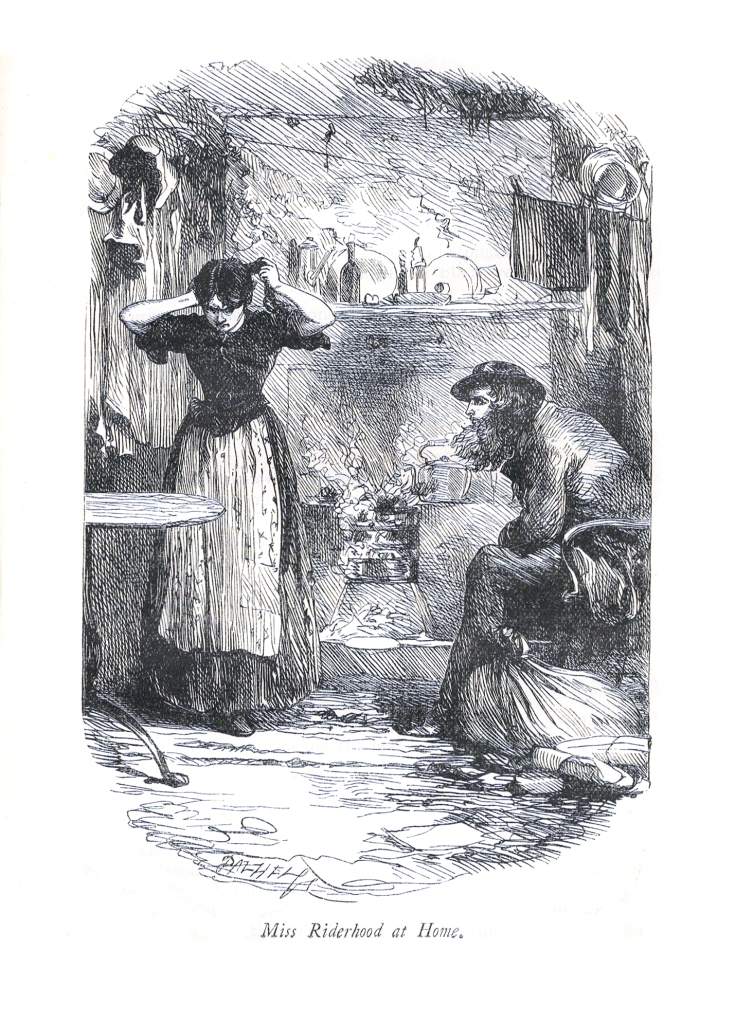

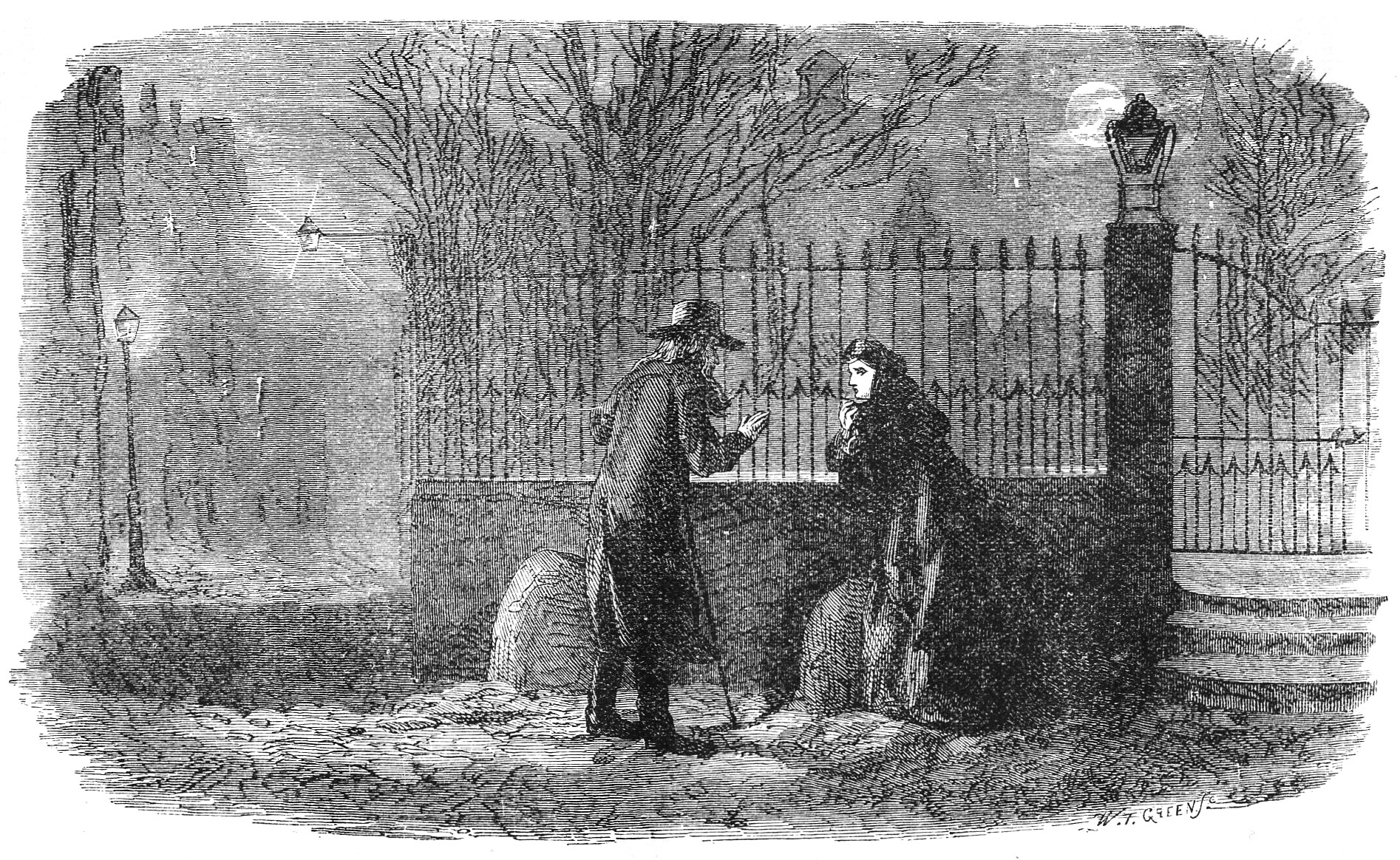

(Illustrated by Marcus Stone. Images below are from the Charles Dickens Illustrated Gallery.)

“The person of the house, doll’s dressmaker and manufacturer of ornamental pincushions and pen-wipers, sat in her quaint little low arm-chair, singing in the dark, until Lizzie came back…”

Charley introduces his schoolmaster, the “decent” Mr Headstone, to Charley’s sister, Lizzie, who is now staying near the river with a young dolls’ dressmaker who calls herself Jenny Wren. Jenny, somewhat disabled with her “bad back” and her “queer legs,” takes care of an alcoholic father and is a little steam engine of work. Shortly after, Eugene visits Lizzie and Jenny—and this hasn’t gone unnoticed by Charlie—offering to help them both to find a little instruction from a tutor. With charm and a bit of dissimulation, Lizzie and Jenny find themselves accepting the offer of help that Lizzie had first rejected. Jenny then talks of the “children” that she has seen in visions since early childhood, with a kind of supernatural eye.

“‘…the children that I used to see early in the morning were very different from any others that I ever saw. They were not like me; they were not chilled, anxious, ragged, or beaten; they were never in pain. They were not like the children of the neighbours; they never made me tremble all over, by setting up shrill noises, and they never mocked me…’”

After a time, Jenny sends Eugene off, as her father is about to come home and she would rather he not see the interaction.

Meanwhile, Veneering is considering running for a parliamentary position, and tries to get Mr Twemlow to advocate for him with his influential relation, Lord Snigsworth.

The Lammles, unable to afford a house, pretend to be looking around while they remain in Lammles’ old digs. In hopes of some future profit to themselves, they continue to cozy up to Miss Podsnap, and try and set her up with young Fledgeby, who, we soon find out, is antisemitic and uses Mr Riah as a kind of scapegoat to treat the debtors of his money lending business harshly. Fledgeby is haunted by the odd Jenny Wren, when he is introduced to her and Lizzie by Riah.

Headstone and Charley then confront Eugene Wrayburn at his lodgings, with Mortimer present. Charley is so rude to Eugene as Headstone stands by to watch his pupil taking Eugene to task, that Eugene effectively ignores Charley altogether and realizes that there is something else going on: an ulterior motive from the schoolmaster. With his usual careless recklessness, Eugene provokes Headstone, and Headstone feels that Eugene thinks of him as little as the dirt under Eugene’s feet.

“‘Do you throw my obscurity in my teeth, Mr Wrayburn?’

‘That can hardly be, for I know nothing concerning it, Schoolmaster, and seek to know nothing.’

‘You reproach me with my origin,’ said Bradley Headstone; ‘you cast insinuations at my bringing-up. But I tell you, sir, I have worked my way onward, out of both and in spite of both, and have a right to be considered a better man than you, with better reasons for being proud.’”

Wegg, meanwhile, is curiously resentful of Boffin’s continued visits to the old “Bower,” as though Boffin distrusts him. Wegg, alongside the disappointed Mr Venus, agree to conspire against Boffin and to share the profits of anything found among the dust mounds.

When Rokesmith suggests to Bella that he would be happy to carry any messages to her family that she wishes him to, as he goes back and forth between the Boffins’s and the Wilfers’s, she is conscience-stricken and goes to visit her family at last. Her prickly relations with her mom and sister haven’t much changed, but she goes to take her father out to lunch with money given her by the Boffins, and makes him use it to purchase a new suit of clothes. She confesses to him her love of money, and her “scheming.”

“‘I have made up my mind that I must have money, Pa. I feel that I can’t beg it, borrow it, or steal it; and so I have resolved that I must marry it.’”

Receiving word that young Johnny, Betty Higden’s child, is ill, the Boffins and Rokesmith persuade Mrs Higden to allow them to help the child to the local Children’s Hospital. Though he has come too late to be helped, he dies peacefully there. Mrs Boffin, heartbroken, wonders whether they should, instead of trying to adopt a young child in honor of John Harmon, shouldn’t instead help Sloppy, who is already so deserving.

Miss Peecher, a teacher with a crush on Bradley Headstone, finds out about his visits to Lizzie, but Headstone doesn’t give himself away. He does visit Lizzie, counselling her not to encourage Wrayburn’s help or visits, but Lizzie doesn’t heed the advice. Headstone suggests that he has something more important to discuss with her at another time.

“Rogue Riderhood dwelt deep and dark in Limehouse Hole, among the riggers, and the mast, oar and block makers, and the boat-builders, and the sail-lofts, as in a kind of ship’s hold stored full of waterside characters, some no better than himself, some very much better, and none much worse.”

A stranger “sailor” visits Pleasant Riderhood, daughter of “Rogue” Riderhood, and when the latter enters, the stranger recognizes a knife belonging to a fellow sailor, George Radfoot. There are questions and suggestions/suspicions exchanged between the men.

We then learn that this mysterious stranger is none other than the one who calls himself John Rokesmith, and the disappeared Julius Handford—and that both are none other than John Harmon himself. Radfoot, who had exchanged clothing with Harmon in a mutual agreement to discover more about Bella Wilfer incognito—but who, it seems, was in some kind of conspiracy with Riderhood—was killed instead of Harmon, but his body was identified as John Harmon’s. So, the real John Harmon continues to watch and wait, trying to discover whether Bella can really love him for himself, and whether he can be justified in, effectively, coming to life again as John Harmon.

“‘To think it out through the future, is a harder though a much shorter task than to think it out through the past. John Harmon is dead. Should John Harmon come to life?’”

One night, however, when John Harmon declares his feelings for her—she knows him only as the secretary, John Rokesmith, of whom she has always had a niggling suspicion—she rejects him.

“‘I have heard Mr Boffin say that you are master of every line and word of that will, as you are master of all his affairs. And was it not enough that I should have been willed away, like a horse, or a dog, or a bird; but must you too begin to dispose of me in your mind, and speculate in me, as soon as I had ceased to be the talk and the laugh of the town? Am I for ever to be made the property of strangers?’

‘Believe me,’ returned the Secretary, ‘you are wonderfully mistaken.’”

Betty Higden, headstrong and independent, wants to leave Sloppy so that he can take advantage of the Boffins’s kindness, and not be continually concerned about her. She won’t take anything except a small loan to make up a workbasket for selling her sewing skills as she travels on foot. Rokesmith helps her with this, and encourages the Boffins to leave her her independence. Rokesmith also hears from Headstone about Wrayburn’s interest in Lizzie Hexam when Rokesmith comes to him about Sloppy’s education.

Shortly following, Headstone makes a violent offer of himself to Lizzie, and at her shrinking, shows that half of his obsession is not so much with her, as for his rival, Eugene Wrayburn, whom Headstone threatens.

“‘Mr Headstone, I thank you sincerely, I thank you gratefully, and hope you may find a worthy wife before long and be very happy. But it is no.’…

‘Then,’ said he, suddenly changing his tone and turning to her, and bringing his clenched hand down upon the stone with a force that laid the knuckles raw and bleeding; ‘then I hope that I may never kill him!’

The dark look of hatred and revenge with which the words broke from his livid lips, and with which he stood holding out his smeared hand as if it held some weapon and had just struck a mortal blow, made her so afraid of him that she turned to run away. But he caught her by the arm.”

Lizzie, who runs out from Headstone’s clutches, is then disowned by her ungrateful brother, Charley, who cannot understand why she would reject a man (Headstone) who would have helped to raise her in the world.

Distraught and weeping, Lizzie is comforted by Mr Riah, who accompanies her to her home. They are met with Eugene on the way, who, with antisemitic quips, tries to get her to take his own arm instead, but Lizzie wants to stay with Riah, so they both accompany her.

Meanwhile, Mr and Mrs Lammle have an anniversary dinner, at which Mrs Lammle tries to get Mr Twemlow to intervene to stop her husband, Mr Lammle, from trying to arrange a match between Miss Podsnap and Flegeby.

Discussion Wrap-Up (Weeks 3-4)

Miscellany and What We Loved–and Didn’t

Friends, let me just say that it was very hard to shorten/summarize the wonderful comments this week! Often, I just opted to try and include as much as possible of all of it–only reorganizing it thematically.

There was so much to love during Book the Second! The Stationmaster loves the portrayal of the warm relationship between Bella and her father, and Bella’s blunt honesty. Dickens goes from this, to the heartbreaking scene of Johnny’s death, which he found more poignant than Jo’s in Bleak House:

The Stationmaster praises Dickens’s ability to misdirect the readers about Rokesmith’s identity, while he is surprised that the revelation has been made so quickly:

Daniel reflects on the wonderful comments, and on Dickens’s ability to make us see “human foibles and goodness from so many angles”:

Character Spotlight: Eugene Wrayburn

The Stationmaster felt a bit annoyed with Eugene for being “insufferably rude” with Headstone when he and Charley confront Eugene about Lizzie:

I take up Eugene’s defense–not altogether, as I have several issues with Eugene–but for this particular scene:

Character Spotlight: Miss Jenny Wren

The Stationmaster reflects on the unique character of Miss Jenny Wren, though he can relate certain qualities of hers to previous Dickensian characters, and finds it interesting that, with all of her mystical experience, “she doesn’t have a particularly sweet or innocent personality”:

I heartily agree with the praise of Jenny, my favorite female Dickens character:

From Chris, on the wonderful Jenny:

Dickens’s Writing Lab: Old & New Characters; Antisemitism and Dickens’s Reparation; Narrative Intrusion; Dickens’s Dark Comedy; Sexual Tension vs. Romance

Here, the Stationmaster considers several of the characters to be–occasionally inferior–rehashes of other Dickensian characters or types. He believes that the Fledgeby/Riah pairing, however, is an improvement on the Casby/Pancks one from Little Dorrit:

Chris adds more character pairings and influences from our previous reads:

I add, as to the character influences from previous works:

Chris reflects on her notice and enjoyment of the comedic aspect of Our Mutual Friend on this reread:

The Stationmaster is fascinated, though uncertain, about what exactly to make of the emphasis on the sexual tension of several character pairings here, versus the emphasis on the friendship/romance of previous novels’s pairings:

Chris reflects further on both the comedy and the villainy here, and also the juxtaposition of Rokesmith’s attitude and action vis-a-vis Bella, with that of Headstone to Lizzie:

Dickens & His Illustrators: Marcus Stone

Here’s the Stationmaster on Marcus Stone:

Questionable Motives; Mysterious Miscellany

The Stationmaster throws out a point of confusion for discussion:

Reflections on Dust

Here, Chris shares a wonderful reflection from Maya C. Popa in Guernica Mag:

Dickens as “The Haunted Man”: A Character Spotlight on Bradley Headstone

I want to include Chris’s reflection on Bradley Headstone, and Victorian marriage re: Dickens’s own situation, in full, as there is so much to grapple with here:

Dickens and the Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital

I wrote:

The History of the Hospital at Great Ormond Street (1852-1914)

Charles Dickens: A Most Unusual Celebrity Endorsement for GOSH

A Look-Ahead to Weeks 5 & 6 of Our Mutual Friend (25 June to 8 July, 2024)

This week and next, we’ll be reading the whole of “Book the Third: A Long Lane,” Chapters 1-16, of Our Mutual Friend. Our portion during Weeks 5 & 6 was published in monthly parts (installments XI-XV) between March and July, 1865.

Please comment below with your thoughts on this portion, or use the hashtag #DickensClub if commenting on Twitter/X.

If you’d like to read it online, you can find it at a number of sites such as Gutenberg.

I’ve read the first four chapters of these weeks’ reading. That’s not very much but I’d like to comment now before I forget anything good from them.

I love the counterintuitive name for the heart of the city: Saint Mary Axe! The contrast between the soft, gentle associations of the first two words and hard, sharp associations of the last one is great. Is Dickens going to explain this appellation later?

In the conversation between Fledgeby, Lammles and Riah in Chapter 1, Dickens really captures how annoying it is when bigots won’t take you at your word but insist on putting you in a stereotype. (In this case, the stereotype of the Jewish moneylender.)

Sweet! It looks like Twemlow came through for Mrs. Lammles. Or is Dickens going later going to reveal that there’s another reason Podsnap changed his mind about Fledgeby?

Chapter 2 shows us new sides of Riah and Jenny Wren. We learn about the former’s dead family and see more vulnerability from the latter as she confides about her problems with “her child” and how she misses Lizzie.

It sounds ridiculous but I find Pleasant Riderhood’s wish for her father to remain comatose so people wouldn’t hate him to be really poignant.

I love Mrs. Wilfer’s speech at her anniversary party about how she wasn’t supposed to have married a short guy and George Sampson’s interjections. The following quote took me a while to understand but once I got the joke, it really amused me.

“I have rarely seen a finer women than my mother; never than my father.”

The irrepressible Lavvy remarked aloud, “Whatever grandpapa was, he wasn’t a female.”

Lavinia’s jealousy over her sister’s romantic conquest reminds me of the Pecksniff sisters and Fanny Squeers. Man, they were a long time ago in Dickens’s career!

We’ve talked about how Bella differs from the archetypal Dickens heroine, but I’d argue she has some similarities with them in her interactions with her father anyway. Your average Dickens heroine, like Agnes Wickfield or Little Dorrit, spreads cheer and comfort throughout her household, making it a pleasanter place to be. And that’s what Bella does when she takes her father out to eat or attends her parents’ anniversary party. It just doesn’t feel the same since she has a more specific and less consistently nice personality.

LikeLike

Another example of Dickens’s reiteration is his use of the London fog as a metaphor. Compare the following:

OMF Book 3, Ch 1:

It was a foggy day in London, and the fog was heavy and dark. Animate London, with smarting eyes and irritated lungs, was blinking, wheezing, and choking; inanimate London was a sooty spectre, divided in purpose between being visible and invisible, and so being wholly neither. Gaslights flared in the shops with a haggard and unblest air, as knowing themselves to be night-creatures that had no business abroad under the sun; while the sun itself when it was for a few moments dimly indicated through circling eddies of fog, showed as if it had gone out and were collapsing flat and cold. Even in the surrounding country it was a foggy day, but there the fog was grey, whereas in London it was, at about the boundary line, dark yellow, and a little within it brown, and then browner, and then browner, until at the heart of the City—which call Saint Mary Axe—it was rusty-black. From any point of the high ridge of land northward, it might have been discerned that the loftiest buildings made an occasional struggle to get their heads above the foggy sea, and especially that the great dome of Saint Paul’s seemed to die hard; but this was not perceivable in the streets at their feet, where the whole metropolis was a heap of vapour charged with muffled sound of wheels, and enfolding a gigantic catarrh.

Bleak House, Ch 1:

Fog everywhere. Fog up the river, where it flows among green aits and meadows; fog down the river, where it rolls defiled among the tiers of shipping and the waterside pollutions of a great (and dirty) city. Fog on the Essex marshes, fog on the Kentish heights. Fog creeping into the cabooses of collier-brigs; fog lying out on the yards and hovering in the rigging of great ships; fog drooping on the gunwales of barges and small boats. Fog in the eyes and throats of ancient Greenwich pensioners, wheezing by the firesides of their wards; fog in the stem and bowl of the afternoon pipe of the wrathful skipper, down in his close cabin; fog cruelly pinching the toes and fingers of his shivering little ’prentice boy on deck. Chance people on the bridges peeping over the parapets into a nether sky of fog, with fog all round them, as if they were up in a balloon and hanging in the misty clouds.

Gas looming through the fog in divers places in the streets, much as the sun may, from the spongey fields, be seen to loom by husbandman and ploughboy. Most of the shops lighted two hours before their time—as the gas seems to know, for it has a haggard and unwilling look.

The raw afternoon is rawest, and the dense fog is densest, and the muddy streets are muddiest near that leaden-headed old obstruction, appropriate ornament for the threshold of a leaden-headed old corporation, Temple Bar. And hard by Temple Bar, in Lincoln’s Inn Hall, at the very heart of the fog, sits the Lord High Chancellor in his High Court of Chancery.

Never can there come fog too thick, never can there come mud and mire too deep, to assort with the groping and floundering condition which this High Court of Chancery, most pestilent of hoary sinners, holds this day in the sight of heaven and earth.

The Old Curiosity Shop, Ch 67:

The day, in the highest and brightest quarters of the town, was damp, dark, cold and gloomy. In that low and marshy spot, the fog filled every nook and corner with a thick dense cloud. Every object was obscure at one or two yards’ distance. The warning lights and fires upon the river were powerless beneath this pall, and, but for a raw and piercing chillness in the air, and now and then the cry of some bewildered boatman as he rested on his oars and tried to make out where he was, the river itself might have been miles away.

The mist, though sluggish and slow to move, was of a keenly searching kind. No muffling up in furs and broadcloth kept it out. It seemed to penetrate into the very bones of the shrinking wayfarers, and to rack them with cold and pains. Everything was wet and clammy to the touch. The warm blaze alone defied it, and leaped and sparkled merrily. It was a day to be at home, crowding about the fire, telling stories of travellers who had lost their way in such weather on heaths and moors; and to love a warm hearth more than ever.

In her 2015 book, London Fog: The Biography, Christine L. Corton sums up Dickens’s use of the fog thus:

Dickens saw that just as much as fog was a part of London life, it was also a metaphor for London itself. In its indeterminacy it could be classed as fog, cloud, or mist; and this allowed him to use the image in many ways. In The Old Curiosity Shop the fog becomes a vehicle for revenge on the part of the natural world against the evil symbol of industry, Quilp; it is not the same oily and greasy fog of the later books but one which is natural and therefore provides an apt source of retribution. The fog described in his later novels reflects a darkening of his view of London. In Bleak House the fog causes the dissolution of the individual in the same way the law seeks dissolution of the individual. It is a world where all suffer from the fog but none seems connected, a world in which confusion and madness take a part and in which enlightenment is denied to those who need it. Dickens’s final completed novel, Our Mutual Friend, reveals a city defined by fog, but is also suggests indeterminacy in the way it divides the city between visible and invisible. Its formless nature is still one that can transform Fledgeby, the villain of the novel, into the righteous Christian, whereas Rich, the Jew, is seen only as the heathen. In Our Mutual Friend both animate and inanimate objects are drowning beneath the fog. (76)

Corton’s four identifiers – indeterminacy, retribution, dissolution, transformation – are apt in terms of Dickens’s writing. He always makes clear that people have choices – indeterminacy – our paths are not fixed but rather depend upon what choice we make. He is a firm believer in reward or punishment – retribution – whether in this life or the next. He takes on big topics (poverty, education, the law, snobbery, etc.) and presents various and varied examples – dissolution – of the effect(s) they produce upon society and/or the individual. And finally, he always believes that the state, society, the individual can change – transform – if it or they truly want to.

LikeLike

I am now up to Chapter 10.

Earlier, I described Our Mutual Friend as having, for Dickens, an unusually high number of characters whom we’re not sure are good or bad until the end. I wasn’t just thinking of Eugene Wrayburn and John Rokesmith. I was also thinking of Ned Boffin who was introduced as a positive character but who now seems like he might very well be a negative one, especially with Silas Wegg’s revelation. This development is introduced almost directly after Rokesmith’s identity was cleared up, almost as if Dickens, having cleared up that mystery, is ushering in a new one to hold the interest of readers.

I haven’t been very amused by the stuff about Wegg reading to Boffin prior to this but the following paragraph is pretty great.

“The Roman Empire having worked out its destruction, Mr Boffin next appeared in a cab with Rollin’s Ancient History, which valuable work being found to possess lethargic properties, broke down, at about the period when the whole of the army of Alexander the Macedonian (at that time about forty thousand strong) burst into tears simultaneously, on his being taken with a shivering fit after bathing. The Wars of the Jews, likewise languishing under Mr Wegg’s generalship, Mr Boffin arrived in another cab with Plutarch: whose Lives he found in the sequel extremely entertaining, though he hoped Plutarch might not expect him to believe them all. What to believe, in the course of his reading, was Mr Boffin’s chief literary difficulty indeed; for some time he was divided in his mind between half, all, or none; at length, when he decided, as a moderate man, to compound with half, the question still remained, which half? And that stumbling-block he never got over.”

In general, I haven’t been loving the comedy of Wegg much so far but the scene in Chapter 6 with Venus and Wegg frantically looking in every hiding place for treasure their reading mentions and Venus dragging Wegg around by his collar with his peg leg dragging behind in the ground was hilarious. It’s also a really great suspenseful scene. There is something I don’t quite get though. Why isn’t Wegg immediately blackmailing Boffin with the will he found?

The scene of Lizzie Hexam finding Betty Higden is so beautiful! Even though the scene is obviously setting Betty up to die, I kept hoping against hope that Lizzie could save her.

It’s interesting that Dickens had Reverend Frank Milvey be embarrassed by his wife’s hostility towards Jewish people, even briefly reprimanding her at one point. (“My dear, why not?”) You might have expected him, as the representative of the church, to be the one worried about the presence of Judaism in the community.

This book, the last one Dickens would complete, has a line that arguably sums up a major theme of his oeuvre. “No one is useless in this world who lightens the burden of it for anyone else.” The heroes of Dickens have always been those who lightened others’ burdens, such as Samuel Pickwick, Sam Weller, Mr. Brownlow, the Maylies, Nicholas Nickleby, the Cheerybles, Little Nell, the Marchioness, Gabriel Varden, Joe Willet, Edward Chester, Tom Pinch, Mark Tapley, the reformed Scrooge, Milly Swidger, Walter Gay, Florence Dombey (eventually), the Peggottys, Betsey Trotwood, Agnes Wickfield, John Jarndyce, Esther Summerson, Mrs. Bagnet, Sissy Jupe, Amy Dorrit, Lucie Manette, Sydney Carton (eventually), Joe Gargery and Biddy. In contrast to these unsung heroes, Dickens has criticized rich celebrities as useless. (Realistically, of course, those celebrities are lightening some people’s burdens a little bit anyway by employing them as servants but that’s besides Dickens’s point.)

Chapter 9 contains one my favorite descriptions of scenery in the book. Maybe my favorite period.

“The trees were bare of leaves, and the river was bare of water-lilies; but the sky was not bare of its beautiful blue, and the water reflected it, and a delicious wind ran with the stream, touching the surface crisply. Perhaps the old mirror was never yet made by human hands, which, if all the images it has in its time reflected could pass across its surface again, would fail to reveal some scene of horror or distress. But the great serene mirror of the river seemed as if it might have reproduced all it had ever reflected between those placid banks, and brought nothing to the light save what was peaceful, pastoral, and blooming.”

It’s interesting that John Rokesmith and Bella Wilfer don’t interact with Lizzie Hexam until this late in the book. Previously, the two main storylines had been happening side by side but with very few of the characters taking part in both. You could easily imagine a book with just the Rokesmith-Bella story or with just the Eugene-Lizzie story. Contrast this with David Copperfield where every subplot is seen through the main character’s eyes. Prior to this, Our Mutual Friend has been more like Barnaby Rudge where the story of Barnaby and the two love stories (Edward Chester and Emma Haredale and Joe Willet and Dolly Varden) are connected by the character of Gabriel and by the Gordon Riots but not much else.

Chapter 9 grants my wish that we see John and Bella enjoy each other’s company and I’m happy to say I’m finally shipping them! I’m still not really on Team Eugene though. When Bella and other characters tell Lizzie she’d be better off forgetting him, my reaction is kind of…. yeah. I wonder if Dickens made a mistake by having the scene of Eugene breaking the news of her father’s death take place offstage. That might have shown their relationship in a better light.

LikeLike