Wherein we conclude our journey with Nell and the grandfather; with a summary of reading and discussion of the fourth week of The Old Curiosity Shop (Week 33 of the Dickens Chronological Reading Club) and a final thematic wrap-up; with a look-ahead to our two-week break and our next read.

Edited/compiled by Rach

“Such are the changes which a few years bring about, and so do things pass away, like a tale that is told!”

Friends, we are at the end of our journey with Nell and the grandfather–and, especially this week, with Dick and the Marchioness! Since our Nell somewhat disappears in this final quarter, it has been, to some degree, “the week of the Marchioness.”

But before we get into our discussion and final thematic wrap-up, here are a few quick links:

- General Mems

- The Old Curiosity Shop, Week Four (Chs. 56-73): A Summary

- Discussion Wrap-Up

- Final Thematic Wrap-Up

- A Look-Ahead

General Mems

If you’re counting, today is day 231 (and week 34) in our #DickensClub! It will be the final day of The Old Curiosity Shop, our sixth read of the group. Please feel free to comment below this post for any final comments about this read, or how you’ll be spending the break between Dickens reads! Or use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter.

Thank you to Chris for her post on the Marchioness! And for alerting us to a musical adaptation of the Shop called Mister Quilp! The Dickens Society has shared a link to the complete film.

No matter where you’re at in the reading process, a huge “thank you” for reading along with us. Heartfelt thanks to our dear Dickens Fellowship and The Dickens Society for retweets, and to all those liking, sharing, and encouraging our Club, including Dr. Christian Lehmann and Dr. Pete Orford. Huge “thank you” also to The Circumlocution Office (on twitter also!) for providing such a marvelous online resource for us.

And for any more recent members or for those who might be interested in joining: the revised two-and-a-half year reading schedule can be found here. If you want to take a look at Boze’s marvelous Introduction to Master Humphrey’s Clock and The Old Curiosity Shop, they can be found here. If you’ve been reading along with us but aren’t yet on the Member List, we would love to add you! Please feel free to message Rach here on the site, or on twitter.

The Old Curiosity Shop, Week Four (CHs. 56-73): A Summary

Schemes are afoot in Bevis Marks as Mr. Brass begins his work of destruction on Kit by his flattery and his offering Kit various little sums of money from a mysterious benefactor, implying that this is the single gentleman.

Kit ends up being more and more a go-between for the single gentleman and the Garlands–becoming fast friends–particularly during and after the former’s illness.

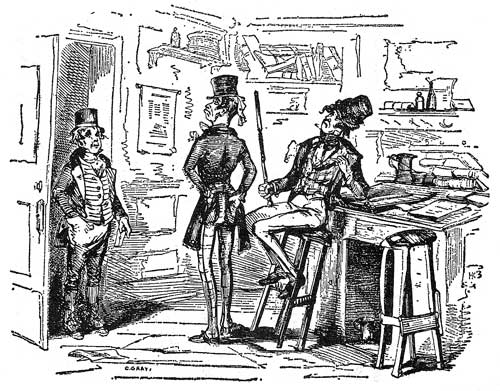

Meanwhile, many of us have become entranced by the unlikely relationship between two lonely characters: Dick Swiveller, often playing a solitary game of cards at the office during periods of particular boredom, and the small servant who resides with (and is abused by) the Brasses. Dick discovers her watching him playing cards at the keyhole; she is fascinated and wants company. He offers to teach her, and they play in her basement dungeon, and he bestows upon her the whimsical nickname, “the Marchioness.” She confesses that she often overhears things—including about the Brasses’ conflicted opinion about himself—and she has also discovered an additional key to the “prison” where she is locked up, so that she can let herself out at odd times and scrounge for some food.

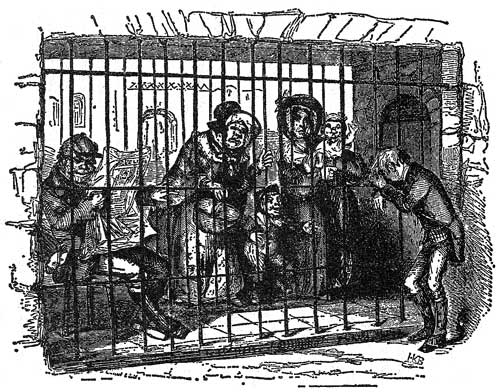

When the Brasses begin to hint about certain items—including money—having gone missing from the office, Dick is fearful that blame may fall upon the Marchioness. Sally suggests that it could also be Kit, who is often there. Dick is sent off while Kit arrives, the latter on another errand for the single gentleman. The single gentleman wants to do something to help provide for Kit’s mother. Brass leaves Kit alone in the office briefly—having planted upon Kit a five pound note to frame him—and once Dick returns and Kit leaves, Brass pretends to be shocked at the money’s loss. Dick and Mr. Brass catch up with Kit, asking him to come quietly back to the office, which he does without hesitation. Dick unwillingly discovers the note in Kit’s hat, and Kit is shocked–and arrested. Further evidence of Kit coming into various amounts of money recently also tells against him.

Kit appeals to Mr. Brass to vouch for him that he has often given him money from his mysterious benefactor, but Brass dodges this, and finally denies it. Kit is enraged.

Quilp has had his revenge on Kit. When Brass comes to visit him, suggesting caution to Quilp about the proceedings regarding Kit, Quilp commands Brass to fire Dick once Kit’s trial is over.

Quilp is now sure there must be money in Nell’s family after all, since someone like the single gentleman is pursuing Nell and the grandfather.

Kit is found guilty. Dick starts to suspect something underhand in the whole thing, but is fired by Brass before he can begin to consider it all.

Then, Dick falls gravely ill. For weeks, he’s been delirious with fever. Upon waking, a shadow of his former self but alive, he thinks he is in a dream or a tale from 1,001 Nights, as there are herbs strewn everywhere, linen being cleaned—and the Marchioness there in his apartment, playing a solitary game of cards. She has cared for him during the whole of his fever, has run away from the Brasses’ home, and has even managed to pawn his wardrobe to get necessary items and pay the medical fees. More than that, Marchioness gives Dick crucial information about Kit: he has been sentenced to transportation abroad; but he is innocent. The Marchioness had overheard the Brasses discussing their plot against Kit—originating with Quilp, who is connected to the Brasses financially—and how they planted the money on him. She has had no one to tell, as the single gentleman was gone from the Brasses’ lodgings.

Dick sends the Marchioness off with a note for the Garlands, and a notary.

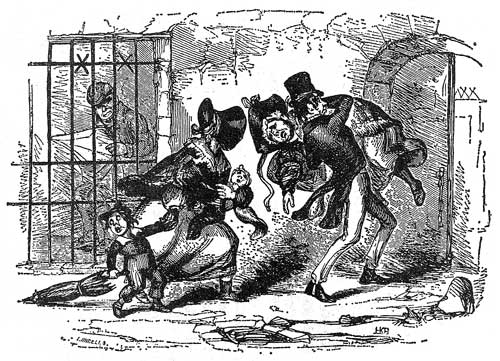

She brings Abel Garland to Dick’s lodgings, where the whole story is related to him. Several others, including Mr. Garland, Mr. Witherden, and the single gentleman, are brought into the knowledge; the single gentleman provides Dick with food and necessaries, and they all go about procuring Kit’s release.

Mr. Brass interrupts a conversation between these gentleman and Sally—they will make a deal with her, if she’ll testify against Quilp, who is behind the proceedings. Mr. Brass, in spite of his sister’s warnings, gives them the information they need, hoping that in doing so, he will make things go easier on himself.

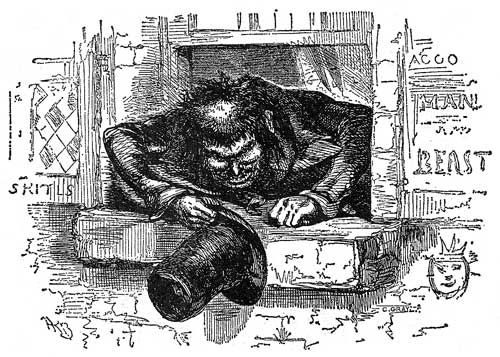

Quilp, at the counting house at the wharf, gets warning from Sally that all has been revealed by her brother. Thinking he hears someone coming for him, he puts out the light, loses his sense of direction, and falls into the water. He drowns.

Kit is released and reunited with friends, family and patrons—including Barbara, and the two of them show their mutual love. Mr. Garland requests that Kit him and the single gentleman on a journey to meet up with Nell and the grandfather. Yes, they’ve been discovered, via information from Mr. Garland’s brother—the “bachelor!” Although Nell and her grandfather are in a safe situation, Nell has fallen very ill.

On the journey, we learn the history of the single gentleman: he is the younger brother of the “grandfather”—the two had long been estranged—and had been in love with the same woman (Nell’s mother). Remembering their childhood closeness and associations, the younger brother has returned, only to find them gone.

The weather is bad on their journey. When Kit enters the grandfather’s house, he finds him in a kind of reverie, and tells Kit absently that Nell is asleep—but something is wrong.

The single gentleman reunites with his brother, but the grandfather seems to have almost no ears to hear nor eyes to see anything other than Nell; he is haunted.

Once they all enter the next room, they find Nell dead—and she had been so for some time. In the coming days, the grandfather’s brother and friends struggle with how to communicate the news to him. The grandfather dies soon after.

“The magic reel, which, rolling on before, has led the chronicler thus far, now slackens in its pace, and stops. It lies before the goal; the pursuit is at an end.”

Quilp’s body washed ashore. His wife profits financially from his death, and is married far more happily after. Mr. Brass is arrested for perjury and fraud, and his sister appears to have been seen in the precincts of St. Giles among the poorest beggars, though we might prefer to think of her as the stuff of legend:

“Of Sally Brass, conflicting rumours went abroad. Some said with confidence that she had gone down to the docks in male attire, and had become a female sailor; others darkly whispered that she had enlisted as a private in the second regiment of Foot Guards, and had been seen in uniform, and on duty, to wit, leaning on her musket and looking out of a sentry-box in St James’s Park, one evening.”

Abel Garland becomes happily married, and goes into partnership with our notary friend, Mr. Witherden. Kit’s pony “preserved his character for independence and principle down to the last moment of his life.” Our bachelor friend ends up living with Mr. Garland after the clergyman dies.

And Dick…?

“Mr Swiveller, recovering very slowly from his illness, and entering into the receipt of his annuity, bought for the Marchioness a handsome stock of clothes, and put her to school forthwith, in redemption of the vow he had made upon his fevered bed. After casting about for some time for a name which should be worthy of her, he decided in favour of Sophronia Sphynx, as being euphonious and genteel, and furthermore indicative of mystery…And let it be added, to Dick’s honour, that, though we have called her Sophronia, he called her the Marchioness from first to last.”

Of course, Dick and the Marchioness marry, once she has come of age—by their best guesstimate, her age having been another subject of mystery.

Kit ends up happily married, prospers in the world, and tells Nell’s story to his children. The poor schoolmaster—now poor “no more”—remains in the country. The single gentleman becomes a kind of Pickwickian benefactor to humanity—and in particular, those who had been kind to Nell and the grandfather–“and trust me, the man who fed the furnace fire was not forgotten.”

Discussion Wrap-Up

Successful Dickensian Couples

The Stationmaster really led the way in our discussion this week, especially about the Marchioness. Although I am placing his first comment under another heading–so as to keep the discussion on Dickens’ Women and the “Writing Lab” in immediate succession–my response to him related to that marvelous couple, Dick Swiveller and the Marchioness:

Boze was equally delighted by this strange pair–specifically, the Marchioness’ unexpected presence in Dick’s lodgings, like something out of the Arabian Nights–which is also Dick’s first thought upon waking after his weeks-long illness. This allusion “really drives home how strange and surreal the experience of being loved is”:

Chris is right in on the celebration of these two quirky worthies! She argues that it is “Dick’s coming of age”–and perhaps just as well for him that he had an annuity and not a lump sum from his aunt–and a happy ending for the Marchioness, whose “life was hell from the start.”

Dickens’ Women: Nell and the Marchioness

The Stationmaster compares Nell and the Marchioness, feeling that the sentimentality surrounding the construction of Nell’s story is too much; that “Dickens keeps reminding us that we should love and pity Nell to the point that it gets annoying.” More than that, the Stationmaster writes, “I agree with Chesterton that the Marchioness is a better heroine than little Nell.”

Lenny considers the differing circumstances in Little Nell’s life versus that of the Marchioness, and have each dealt with it somewhat differently–the Marchioness becoming a “detective” of sorts:

Marnie doesn’t see as much dissimilarity between Nell and the Marchioness, and argues that “the novel belongs to Nell”:

Dickens’ “Writing Lab”: Comedy, Characterization, Deaths, “Multiple bildungsromans,” and “Surprise Heroes”

I’m highlighting this passage from the Stationmaster, as he brings up a crucial question, in terms of Dickens’ writing choices:

We’ve pondered our preferences vis-à-vis Nell and the Marchioness, and we move into a discussion on why one works better as a potential leading lady. Was there too little of Little Nell in the final quarter, or too little of the Marchioness early on, so that the latter’s sudden involvement in the story really takes over?

Lenny responds, suggesting that “the last 1/4 of the novel BELONGS TO THE LONDONERS who carry the narrative forward as they define their own meaningful quests in life. Could we say that this novel has multiple bildungsromans!?”

I responded to the Stationmaster and Lenny by considering that it is that essential combination of comedy/quirkiness in the midst of a situation of pathos that can make some characters more effective in Dickens:

The Stationmaster had commented on the comedy right at the outset. He also writes of the appropriateness of how Quilp meets his end:

We were so glad to see Daniel back to join in our discussion, and he comments on Dickens’ ability to draw characters “with starkly drawn contours,” whose “physical attributes often seem to ‘mirror’ their mental-moral qualities”:

The Stationmaster had another fantastic point about the essential purpose–or lack of it–for Nell’s death, thereby questioning Dickens’ choice. “Usually,” he writes, “when a sympathetic character dies in Dickens, it’s important to the plot or furthers the book’s social message…Nell, on the other hand, is shown to be quite capable when she’s not ill,” and that “there’s really no reason why her story couldn’t have had a happy ending”:

The Stationmaster considers Dick as “the character in the book with the most range, morally speaking,” and that he ends up “becoming the surprise hero of The Old Curiosity Shop“:

And Chris agrees. Dick is “the regular guy who does the right thing”:

Final Thematic Wrap-Up

In keeping with our “Final Wrap-Up” tradition, I’ve tried to pull together the primary themes we’ve discussed in our journey with Nell and the grandfather–those which are new to this read, and those which have carried over from Dickens’ Sketches and novels from the outset:

- Dickensian Contrasts: Nell and the Curiosity Shop, Light and Shadow, Comedy and Tragedy (We’ve all discussed this; Nell in stark contrast with her surroundings. Chris wrote of Nell, in reverse of Dickens’ line: “Nell is majestic youth surrounded by perpetual age!”)

- Crime and Violence (Quilp; Marnie and Rach both felt Quilp almost too difficult to read about sometimes. The Stationmaster remarks on the appropriateness of Quilp’s demise.)

- Mental Health, Trauma, and Addiction (We discussed this particularly in the first week; Rach discussed addiction and the “Gollum-like” nature of the grandfather as he steals from his own granddaughter in the middle of the night, like a figure of nightmare. Lenny has often referred to the grandfather’s mental illness or “dementia.”)

- Theatricality; the Dream-World vs. Reality (Boze and Rach focused on the dreamlike nature of The Old Curiosity Shop with its 1,001 Nights references and the strangeness of the surroundings; the repetition of certain words–e.g. “dream”–or of Quilp being referred to as an ogre/ogreish; even the grandfather becomes a figure of nightmare (see “Addiction”). Lenny, Chris, and Marnie had wonderful insights on its often stark reality; Lenny saw Quilp as more along the lines of a sharp-practicing businessman.)

- Consumption (Lenny and Rach discussed this especially; Quilp, the “ogre,” is consistently “consuming” those around him.)

- Money (Recurring theme in Dickens; here, it is either greed, cruelty, or both that pursues Nell and the grandfather at every turn–until friends come to their aid.)

- Dickens’ Women (Perhaps the most prominent theme this month; in particular, comparing/contrasting Nell and the Marchioness. But Chris also had the most marvelous things to say about Miss Brass, and the Stationmaster did on Mrs. Jarley. The Stationmaster defended Nell as a truly “active” protagonist. While most of us really liked Nell–Marnie was a very eloquent advocate for her–many of us found a greater character in the Marchioness–Lenny, Rach, Chris, and the Stationmaster especially; the Stationmaster really led the discussion here during our final week. Chris shared a marvelous post on the Marchioness. Lenny suggests that we might even call the Shop and Nickleby “womens’ novels”; he is reminded of Mary Wollstonecraft and sees Nell potentially as a “symbol of female subjugation.” Chris: Nell is Dickens’ ideal, “the silent helpmeet who bears all, believes all, hopes all, but who also sees all, manages and tolerates all. It’s no wonder then that Nell wilts under the burden.”)

- City vs. Country; Dickens’ Romanticism (We have all referred to this in one way or another; Rach loved the descriptive passages about the industrial city and its Blakean “dark Satanic Mills.” Lenny discussed the contrast between “the smog-filled environs” to “the wide open and freeing spaces of the country.” Lenny also wrote beautifully about “Romanticism” in the wrap-up of our first week, wondering whether the Shop might be Dickens’ “most Wordsworthian novel,” and that perhaps the “fairy-tale” quality of it is more akin to Wordsworth’s grappling of psychological realities, his “unknown modes of being.” Boze wrote of the “lyricism” of our Week Three reading portion: “his prose acquires a new urgency, an intensity and lyricism and poetry he hadn’t shown to date in any of his previous works. There’s a momentum to the final quarter of the novel, like a train travelling across country.”)

- Mutability and Mortality (Lenny first brought this theme up early on during our journey with Dickens; though we’ve not addressed this theme by name, it saturates The Old Curiosity Shop.)

- Memory (Again, an ongoing theme in Dickens; manifesting particularly in Nell’s lament at the unvisited graves.)

- Benevolence as Reconciling Influence (Particularly in the Garlands, the single gentleman, and Mr. Morton.)

- Dickens’ “Writing Lab”: Characterization, Contrasts, “Surprise Heroes,” Sentimentality; Allegory; the Ability “To Leave Something Always In Suspense” (We’ve all talked about this in one degree or another. We discussed the “sentimentality” that Shop is often accused of as having–and Marnie really spoke in Dickens’ defense; Lenny was struck by the realism of the portrayals this time around; Boze marveled at Dickens’ ability to appeal to contemporary sensibilities and also his ability–essential for a writer–“to leave something always in suspense.” Chris and Daniel wrote of allegory, and Dickens’ ability to lift characters to the level of allegory without losing their individuality; the Stationmaster was an eloquent advocate for such “surprise heroes” as Dick and the Marchioness.)

- Dickensian Children: Childhood as a “Special State”; Children Taking the Role of Adults (From our wrap-up of the first week. Lenny discussed the “wounded” children in Dickens during our wrap-up of Week Two–this is all representative of a larger systemic fault.)

A Look-Ahead

Friends, what a delightful journey it has been. We’ll now be enjoying a 2-week break from our scheduled reads just in case you want to add in extra non-Dickensian reading, or what Chris calls our “in-between readings”–which, for many of us, are just extracurricular Dickensian material!

Our updated schedule can be found here.

A few of us might still keep up the conversation during the break. Otherwise, I very much look forward to seeing you on September 6, for Boze’s introduction to Barnaby Rudge!

I’ve got 12 chapters left to read but I accidentally spoiled the story for myself so I’m familiar with what happens. Thank heavens for the Marchioness!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh YAY!!!! So glad you’re there, Cassandra, though I’m so, so sorry about the spoilers–that’s the worst! Yes, I feel like the theme this week is, “Thank heavens for the Marchioness!”

LikeLike

Thanks, Rach, for the wrap-up!

Forgive me if this has been addressed in previous convos–I’m catching up here–but I have a quick question for Boze, or anyone else in the know, re Dickens’ fascination with the Arabian Nights; i.e., which translation was it? \

I ask, because I’ve always been fascinated, as well as (often) repelled by the life and career of Sir Richard Francis Burton, who translated the AN in an infamously, ahem, “unexpurgated” version in the 1880s. I suspect the one with which CD was familiar was considerably tamer.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such a good question! I am curious now, too…Boze and I have talked recently about the Nights, as I’ve been wanting to read them. Boze gave me a wonderful lesson in the various translations! But I wonder which translation our Boz would have known…? The refs are everywhere!! As Boze recently mentioned (I think), there are more Dickensian refs to Nights than to any other work(??)

LikeLike

In our beloved and often quoted biography, “Dickens”, Peter Ackroyd tells us:

“. . . ‘The Arabian Nights’ . . . is arguably the most important of all literary influences upon Charles Dickens. That saga, together with ‘Tales of the Genii’ . . . is constantly recalled both in his fiction and in his journalism; recalled, too, in his life on those occasions when his own anxious musings send him plummeting back to that magic world first opened to him in his childhood. And how could it not be so? . . . [Dickens] pointed to the childhood reading of these fantastic tales as the way to nourish both the Fancy which leads to gentleness and the Imagination which encourages sympathy or mercy – the tales’ ‘simplicity, and purity, and innocent extravagance’ eliciting in turn ‘Forebearance [sic], courtesy, consideration for the poor and aged, kind treatment of animals, the love of nature, abhorrence of tyranny and brute force . . . ‘ It lies at the very centre of his belief , and its source is to be found here, in the small room at Chatham. . . .

“His own appetite for such marvels seems to have been endless. ‘In all these golden fables,’ he once wrote, ‘there was never gold enough for me. I always wanted more. I saw no reason why there should not be mountains and rivers of gold, instead of paltry little caverns and olive pots . . . For, when imagination does begin to deal with what is so hard of attainment in reality, it might at least get out of bounds for once in a way, and let us have enough.’ And this vision stayed with him. When in later life he discusses gold and money, he almost always alludes to ‘The Arabian Nights’ as if his own appetite for such things were boundless; when in his journalism he discusses the most modern industrial or commercial processes, he similarly invokes the spirit of these tales, in part no doubt to romanticizse [sic] that which seems alien and ugly, but also in part to create a sense of fabulous communion with his reader, using childhood and the values of childhood as the arena common to all people and one which can naturalist the most forbidding contemporary phenomena. The attempt is rarely successful, however, and the introduction of this magical landscape only serves to emphasise [sic] its difference from the real landscapes of nineteenth-century Britain. In his reading of ‘The Arabian Nights’, in fact, there is something so eager, so overwhelming. So obsessive that it really suggests images of childhood anxiety and deprivation – so it is that, in his use of ‘The Arabian Nights’ in his later writing, there is often latent within his references an overwhelming mood of incongruence and sadness. Childhood has gone for ever, his own and that of his age.” (45-47).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Further to the Arabian Nights question – In Dickens’s library are/were the following volumes:

“Arabian Nights Entertainments, revised from the Arabic, with New Tales now first translated, and Notes illustrative of the Religion, Manners and Customs of the Mahummedans”, ed. Dr Jonathan Scott, dated 1811

and

“The Thousand and One Nights; or, Arabian Nights’ Entertainments”, ed. Edward William Lane, dated 1859

The first entry above was published the year before Dickens’s birth so it may be the one he read as a boy.

My source for this is Dickens Library Online, http://dickenslibraryonline.org/, which is a searchable “catalogue of all titles known to have been owned by Charles Dickens at any point during his lifetime, or by his eldest son Charles Jr. between 1870 and 1878, compiled from all sources currently available to the researchers”. It’s great fun to browse through and helpful at times like the present.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Chris, that’s amazing!! Thank you!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m really excited for the Barnaby Rudge discussion. I’d heard it described as Dickens’s worst book or one of his worst, but I actually found it be an engaging and even fascinating read. I wouldn’t describe it as Dickens’s best book or anything, but I liked it better than The Old Curiosity Shop and, while Martin Chuzzlewit’s high points are probably higher, the quality of Barnaby Rudge is more consistent.

That being said, I haven’t yet like reading it more than once. (Ironically, I’ve reread or tried to reread Dickens book I’ve enjoyed less more often.) I don’t whether I’ll feel like reading it by the time the break is over, but I’m really interested to read everyone’s comments and see if others agree with me that it’s a hidden gem or if they’ll be like, “man, this is the worst book the group has done so far!”

Although WordPress doesn’t seem to recognize any of my emails when I try to “like” anyone’s comments, I’d like to assure everyone that I’ve loved reading the discussion and comparing everyone’s perspectives. The Old Curiosity Shop was the first book we’ve done where I actually did the reading for each week. (For the others, I just commented random things I remembered from my last reading. That’s why my comments were unusually long.) If I’m not in the mood for Barnaby Rudge, I won’t be reading along for a while since I want to keep myself fresh for David Copperfield. But I’ll be keeping an eye on this site.

Since people were interested in my blog posts about Nicholas Nickleby adaptations, I’m sharing a recent one I did about the best screenplays you can read online which are adapted from classic literature. Two of them are based on Dickens books, though one of them is more of an honorable mention. Sadly, neither of them is an adaptation of The Old Curiosity Shop or Barnaby Rudge, but the parts of the blog post about Dickens only amount to a couple of paragraphs, so they shouldn’t take too much time for anybody to read. https://theadaptationstation.com/2022/08/another-list-of-screenplays/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Stationmaster – I agree that Barnaby Rudge is under-appreciated. I think it holds together and holds up better than Curiosity Shop partly because it had been on the back burner in Dickens’s mind for some years and had time to cook, so to speak. I found it got better with the re-read(s).

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m really looking forward to reading Barnaby again – I think it’s the only Dickens novel I’ve read just once? (And it has been a long time, so it’s really hazy in my recollection.) Between what Chris and Stationmaster are saying here, and recent conversations with Dr Christian and with Boze, I feel like this is one to look forward to and get to know better.

LikeLike

Hi Rachel, thank you for your marvelous wrap-ups along the way – and a belated word of thanks, as well, for your kind welcome last week to the DCRC. I have very much enjoyed all your comments and discussion “after the fact” as I read like a maniac to catch up on _Curiosity Shop._ This morning, I woke up early to polish off the last chapters before the final wrap-up came out. I was crying into my first cup of coffee! Here follow my late contributions to the discussion.

The Adaptation Stationmaster writes that “the Marchioness is … just as much a Victorian character type as Nell.” Similar though they are in many external details (e.g. young girls, orphaned from youth, badly used by adults, tested by extreme hardships), it seems to me these two girls are examples of two quite different character archetypes. The Marchioness is a survivor, but our little Nell is a martyr — the oldest Christian archetype there is.

Of course, this does not mean she is merely a passive sufferer. I appreciated and agree whole-heartedly with Marney’s point that she shows herself capable of positive action “at practically every turn in the novel!” The heroism of a martyr is not their passivity in the face of torments, like poor St. Catherine on her wheel, but in the _will_ to stake everything, even life itself, on some higher good, laying down everything one has out of love without so much as a backwards glance. This quality of soul, this magnanimity, shines forth from little Nell as early as chapter 7: “Let us be beggars, and be happy!” What the grandfather dismisses as childish naïvete, Nell rather makes bold to defend as the martyr’s clear-sighted appraisal of eternal goods (love) weighed against passing temporalities (money):

“‘Dear grandfather,’ cried the girl with an energy which shone in her flushed face, trembling voice, and impassioned gesture, ‘I am not a child in that I think, but even if I am, oh hear me pray that we may beg, or work in open roads or fields, to earn a scanty living, rather than live as we do now … If you are poor, let us be poor together; but let me be with you, do let me be with you … Let us walk through country places, and sleep in fields and under trees, and never think of money again, or anything that can make you sad, but rest at nights, and have the sun and wind upon our faces in the day, and thank God together!’”

The Adaptation Stationmaster remarked that “there’s really no reason why her story couldn’t have had a happy ending. … Dickens chose to give it a sad one for sadness’s own sake.” On the contrary, I do think Nell has to die at the story’s conclusion, because the martyr’s self-gift is all-consuming. I’m persuaded here by Lenny’s comments on _raison d’être_. By the time she and her grandfather arrive at the village in chapter 55, Nell’s raison d’être — her love for her grandfather, which compelled her to take him out of London and drove her on through all the trials and tribulations since, in hope of some final pleasant place where they could find rest and happiness together — is fulfilled. Literarily, Dickens “has no more to give her to do” — and to invent some other ending for her wouldn’t “fit” the character of Nell. From the moment they steal out of the old curiosity shop and step into the street, Nell is on a _via crucis_ — which can only end at Calvary and the tomb. (Of course, we — like Nell and her grandfather — can see this only in retrospect. Who knows, when we first set out, where the road we walk upon will lead in the end? And who would have the courage to take a second step if he did?)

Having fulfilled her mission, Nell becomes the village church-keeper. Did anyone else think that the deep well in the heart of the old church, which the sexton suggests “might have been dug at first to make the old place more gloomy, and the old monks more religious,” symbolizes not only the passing of life (the water which is used up slowly over decades until one day the bucket scrapes the bottom), but the “opening up” of life into eternity? The well is literally an opening up in the earth, which delves to depths too deep for the eye of man to pierce. The image of standing on the brink, gazing into darkness “so deep and so far down, that your heart leaps into your mouth, and you start away as if you were falling in” — that mixed desire and terror of the depths one feels when gazing down — makes me think of our human longing for “deep down things,” as Hopkins says. To go into that darkness is a death, but what “deep down things,” solid, eternal things, may await?

Maybe I am reading this with my theological glasses on, but others have commented that Nell seems a literary stand-in for Dickens’s sister Mary, lately deceased, and as Rachel quotes from Peter Ackroyd in her excellent essay on Dickens and memory: “Dickens’s own religious sensibility began to develop as a result of Mary’s death … He was consoled ‘above all’ by ‘the thought of one day joining her again where sorrow and separation are unknown’.” That the well-scene in ch. 55 is not only a foreshadowing of the end of Nell’s life, but also a hint at the hope of life without end, seems confirmed by this final exchange:

“The child still stood, looking thoughtfully into the vault.

‘We shall see,’ said the sexton, ‘on what gay heads other earth will have closed, when the light is shut out from here. God knows! They’ll close it up, next spring.’

‘The birds sing again in spring,’ thought the child, as she leaned at her casement window, and gazed at the declining sun. ‘Spring! a beautiful and happy time!’”

If I am not mistaken, these are Nell’s last words in the novel. Unlike the sexton, always planning for next summer’s work, little Nell longs for spring, that season of new life and new beginnings. The winter sun sets, but she gazes beyond it with the hope for spring eternal. (And might not the longing for country places — a theme on which many of you have spoken eloquently — be an expression, too, of the longing of the human heart for the “pleasantest place” of all, where life and happiness have no end?)

May her memory be eternal!

Some final miscellaneous thoughts:

Like the Stationmaster, I was moved by the passage on the grandfather’s grief, “the blank that follows death.” I was really touched by the description of Nell crying out for Kit in her last days. She never forgot her first friend, just as he hoped she might not! Kit became my favorite character at this line in ch. 14 and remained so through to the end:

“It must be especially observed in justice to poor Kit that he was by no means of a sentimental turn, and perhaps had never heard that adjective in all his life. He was only a soft-hearted grateful fellow, and had nothing genteel or polite about him; consequently, instead of going home again, in his grief, to kick the children and abuse his mother (for, when your finely strung people are out of sorts, they must have everybody else unhappy likewise), he turned his thoughts to the vulgar expedient of making them more comfortable if he could.”

Every Pickwick needs his Sam, and every mother deserves her Kit!

The idea of the grandfather as villain is a troubling one. He’s a victim in his own way: of old age and feebleness of mind, and the slow consumption by addiction of his health, his fortunes, and the happiness he and Nell once shared. He is a fool, in many ways, but not a villain. Because of him, Nell grew up knowing what it is to be loved and delighted in. That’s something the Marchioness never seems to have known, until she met Dick. Maybe that accounts for the difference in their characters and heroic journeys.

Bless you all, and I’m heartily looking forward to joining in future discussions!

LikeLiked by 4 people

Deacon, your take on Nell is a far better defense of the character than my own clumsy attempt. It reflects my own view and admiration for her. As I was reading your account, it occurred to me that perhaps this was why there’s such a disconnect between how positively Dickens and most of his readers at the time felt about Nell and how negatively later readers and critics came to view her. As society became more secularized, this central self-sacrificial aspect of Nell and her journey seems to have become less understood and appreciated, and may have contributed to the cooling in affection for the character. Perhaps Nell’s death and spiritual transport is something that only truly speaks these days to those of us who share the same spiritual perspective of Dickens and his times.

Dickens laid out a foretelling of Nell’s end in chapter 55, just before the shift to the London characters in 56. After the old sexton describes the old well (the grave, so well described by Deacon Matthew), Nell then goes to the old church and sits among the tombs in there and “felt that now she was happy, and at rest” in her acceptance of her approaching death, and then she goes up into the tower – metaphorically rising from death into the heavens – and she reaches the top (heaven itself): “Oh! the glory of the sudden burst of light … It was like passing from death to life, it was drawing near to Heaven.” When the bachelor takes Nell down into the crypt, his description of it – “and showed her how it had been lighted up in the time of the monks, and how, amid lamps depending from the roof…and told their rosaries of beads” – there’s a note in my edition that the “passage contains echoes of the opening stanzas of Keats ‘The Eve of St. Agnes’”. I don’t see much of a resonance between the OCS passage and the Keats 1820 poem (a familiar subject of Pre-Raphaelite painters like Millais), but I checked out Tennyson’s 1837 “St. Agnes” poem and was moved to find lines that called to my mind Nell’s death and her soul’s transcendence to heaven as depicted in the final illustration. St. Agnes was a young girl who died a martyr (self-sacrifice) around 304 and is the patron of virgins – therefore a type of Nell, herself a virgin who sacrificed herself for a loved one. Tennyson wrote in his Agnes poem: “My breath to heaven like vapour goes:/ May my soul follow soon! … Break up the heavens, O Lord! And far, / Thro’ all yon starlight keen, / Draw me, thy bride, a glittering star, / In raiment white and clean. / He lifts me to the golden doors; / The flashes come and go; / All heaven bursts her starry floors, / And strows her lights below, / And deepens on and up! The gates / Roll back, and far within / For me the Heavenly Bridegroom waits.” And, of course, as has been mentioned, Nell was herself a type of Mary Hogarth. Dickens’ inscription for Mary Hogarth’s grave could have adorned Nell’s (or Agnes), apart from the age: “Young, beautiful, and good, God numbered her with His angels at the early age of seventeen”.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Marnie, also *such* a beautiful reflection! I love your allusion to Keats and Tennyson here. Gosh, I am sad that I don’t have a “wrap-up” during the break, in order to highlight the comments here…perhaps I’ll make a kind of “appendix” to the first wrap-up of Barnaby after the intro, just to highlight some final words on the experience with Nell and the grandfather 🖤

LikeLiked by 2 people

Never say that about your comments, Marney. At least not about your comments on this book. They were great.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Wow, dear Deacon Matthew, what an extraordinarily beautiful reflection on Nell and on all of our characters here! I feel this deserves its own essay/post entirely. Thank you for tour thoughtful comments. Because of this notification coming through during our delightful podcast chat, I’d almost forgotten I had a comment (actually, Beautiful Reflection!) to read after! Marnie’s response (which I’m looking forward to reading) alerted me to it!

Thank you for your extraordinarily inspiring and truly Dickensian perspective…I think you captured what Dickens was trying to do here with Nell. I know it was one of the most difficult passages for him to write. (Her death.)

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for keeping the discussion alive, Deacon. I wasn’t going to respond since I feel like I’m ready to move on from this book, but since others have responded, I decided to do so just a little bit.

I still think of the grandfather as a negative character. Not as bad as Quilp obviously, but at best he seems weak and pathetic. And at his worst, he seems downright ungrateful to Little Nell. (Fortunately, he’s not at his worst for long and is usually grateful to her.) It’s true that he provided for Nell when she was young, but I don’t think he should get credit for teaching her about love. After all, he raised her brother too who didn’t turn out so well.

I guess the part of reason I don’t find Nell’s martyrdom as meaningful as you do is I don’t feel like her grandfather was worth it. Actually, that’s not true. I believe everyone has an obligation to their family members, so I applaud Nell’s loyalty and devotion, but I still feel they led to her short life being wasted, especially since the grandfather ends up dying anyway.

There are a lot of depiction of heroic daughters devoted to father figures who don’t deserve them in Dickens. (This group has already covered one in Madeline Bray.) But The Old Curiosity Shop features the only one who doesn’t outlive her ball and chain. Maybe that’s another reason it’s one of Dickens’s glummest books.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Inimitables,

I’m a true Johnny-come-lately, and have so very little to add to the rich tapestry of thoughts, insights, and considerations.

Just one little post-script: I delighted in Deacon Matthew’s expansion on “raison d’être.”

This essential notion/truth impels us to understand that everyone’s life is oriented towards some good (or goods)–often, wrongly perceived as a good (e.g., the control/domination “good” of Quilp).

This seems to me to be a core hermeneutic: What is this character’s raison d’être? What good draws, drives this person?

What causes her/him to wake up in the morning? What explanatory lens helps us to grasp the motivation, the spring of her/his acting?

Anyway, I am in great admiration of all of the comments, and can honestly say that a graduate seminar on “The Old Curiosity Shop” could not have enriched me to the same degree.

Blessings during the break!

Daniel

LikeLiked by 2 people

I agree with Daniel! What a beautifully rich series of comments brought forth by all in this post-reading segment of CURIOSITY SHOP. The main presenters, Deacon, Marnie and Chris all fill in more gaps in the process of helping us to understand the intricacies and subtleties of CS! The inclusion of Tennyson’s “St. Agnes” is a wonderful complement to Deacon’s discussion of Nell as Christian “archetype,” and I love Chris’ discussion of Dickens’ thorough readings and appreciations of THE ARABIAN NIGHTS. Again, as one who loves to survey the notion of the dynamics of reader response, I find this latest group of of responses to be a marvelous set piece of opinions and ideas.

I’m also very much aware of the significance of Cassandra’s statement–“Thank Heavens for the Marchioness!”–as she notes that as a theme for much of our later discussion of CS. And in this regard, I feel that much of the laudatory post-reading discussion, here, is a kind of compensatory reaction to the issue of our positive declarations for the character of the Marchioness as the heroine, or “dual heroine” of the novel. And so, in our respective readings therein, we are trying to regain in our latest commentary the earlier traction inherent in our comments about Little Nell. And, thus, we have developed a kind of group competition within our assessments of the two young heroic women. Stationmaster brought this forth some time ago when he began to demonstrate HIS particular veneration foactive and surprising function of Marchioness vs the sort of sad and depressing journey that Nell makes with her grandfather. I believe the novel has it both ways and that the two young “women” each act out her own particular and peculiar narrative according to the embedded characteristics of their differing personalities. Nell is “Nell” and the Marchioness is “the Marchioness”; full stop (!) and they each, from a structural standpoint, move the novel along beautifully. Both reflect–in very different ways–the requisites that Dickens feels are NECESSARY to advance the novel’s plot or its “narrative progression.”

So from another viewpoint, we are dealing with the STRUCTURE of the novel and Dickens’ realization that successful progression demands inventive ideas and new surprises. And the resurrection (if you will) of the Marchioness out of the depths of the basement (with the help of Swiveller, etc.) fulfills this rhetorical “task.”

At the same time. as we’ve mentioned in our past analyses of the earlier novels, this novel incorporates big time Mr. D’s use of the zig-zag narrative, where he has several narrative movements or “subplots” going at once, continually shifting from one to the other. And I believe from NICKLEBY on, this use of parallel narratives is growing in complexity–as we see it in CS. In short, our dear author has quite a juggling act going on here in this novel. Just think, for a moment, of the various schemes Quilp is involved in–as he is probably the major catalyst in the novel: Quilp vs Grandfather; Quilp vs Nell; Quilp vs Kit; Quilp vs Dick; Quilp vis-a vis Sampson and Sally–and the list goes on. So there is this constant narrative shifting, and our roles as readers just becomes even more complex and sometimes just downright difficult–for any number of reasons. We like one character, we despise another character, we have ambiguous feelings about others and, as the novel advances, many of these earlier perceptions are subject to change and many of these perceptions ARE modified…so that there is a HUGE complex of ideas and feelings happening as our “readings” of these characters and events are continually being challenged and transformed.

Hence the newer ramifications in this later group of comments! And there are probably on-going considerations about all of this even as I write these paragraphs. The dynamic just keeps happening ad infinitum! And I’m sure, when we get into BARNABY, we will continue to refer to elements of CS that our new novel will compel us to write and think about!

LikeLiked by 1 person

In case it wasn’t clear, I feel like I should stress that I don’t think books should never be depressing per se and I don’t really have a problem with passive main characters. (And, like I argued, neither Nell nor the Marchioness is really passive.) I just don’t find to be as consistently well written as some other books of Dickens. And the fact that it’s one of his most hopeless makes me wonder if maybe complete tragedies weren’t his forte. He certainly could write stories with depressing parts and tragic elements well though!

LikeLiked by 1 person