WHEREIN WE REVISIT OUR first and second WEEK’S READING OF Bleak House (WEEKs 76-77 OF THE DICKENS CHRONOLOGICAL READING CLUB 2022-24); WITH A CHAPTER SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION WRAP-UP; CONTAINING A LOOK-AHEAD TO WEEKs three and four.

By the members of the Dickens Club, edited/compiled by Rach

Friends, what a lively discussion we’ve had so far about Bleak House, beginning with Boze’s introduction 2 weeks ago! We’ve discussed parental neglect, telescopic philanthropy, our response–as readers–to Esther, as well as the unknown omniscient narrator of the novel’s 3rd person “portion.” We’ve even discussed how an ancient battle long ago serves as a doubling mechanism for the interminable case of Jarndyce & Jarndyce.

The discussion was so dense and lengthy that I used more snippets and summarization than usual, while trying to make sure we have everyone’s input. I’d very much recommend visiting–or revisiting–the comments under our introduction and under the Stationmaster’s essay from our opening week.

First, a few quick links:

- General Mems

- Bleak House, Chs 1-16 (Weeks 1 & 2): A Summary

- Discussion Wrap-Up (Weeks 1 & 2)

- A Look-Ahead to Weeks 3 and 4 of Bleak House (27 June to 10 July, 2023)

General Mems

SAVE THE DATE: Join us for our online discussion of Bleak House! Saturday, 12 August, 11am Pacific (US)/2pm Eastern (US)/7pm GMT (London)! Please feel free to message Rach here on the site, or on twitter, to get on the list for the Zoom link that she’ll send out in early-August.

If you’re counting, today is Day 539 (and week 78) in our #DickensClub! This week and next we’ll be on Weeks 3 and 4 of Bleak House, our eighteenth read of the group. Please feel free to comment below this post for the third and fourth week’s chapters, or use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter.

No matter where you’re at in the reading process, a huge “thank you” for reading along with us. Heartfelt thanks to our dear Dickens Fellowship, The Dickens Society, and the Charles Dickens Letters Project for retweets, and to all those liking, sharing, and encouraging our Club, including Gina Dalfonzo, Dr. Christian Lehmann and Dr. Pete Orford. Huge “thank you” also to The Circumlocution Office (on twitter also!) for providing such a marvelous online resource for us.

And for any more recent members or for those who might be interested in joining: the revised two-and-a-half year reading schedule can be found here. For Boze’s marvelous introduction to Bleak House and for our reading schedule, please click here. For Chris’s supplementary intro reading material, please click here. If you’ve been reading along with us but aren’t yet on the Member List, we would love to add you! Please feel free to message Rach here on the site, or on twitter.

Bleak House, Chs 1-16 (Weeks 1 & 2): A Summary

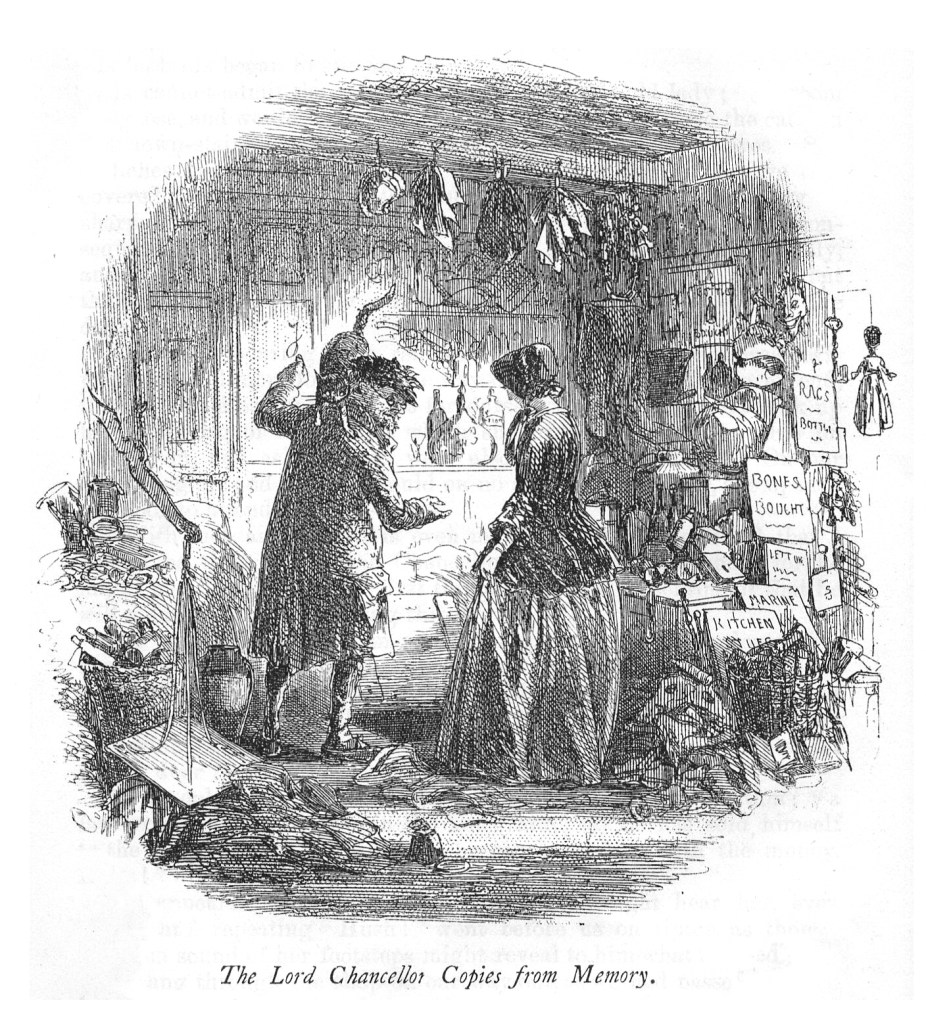

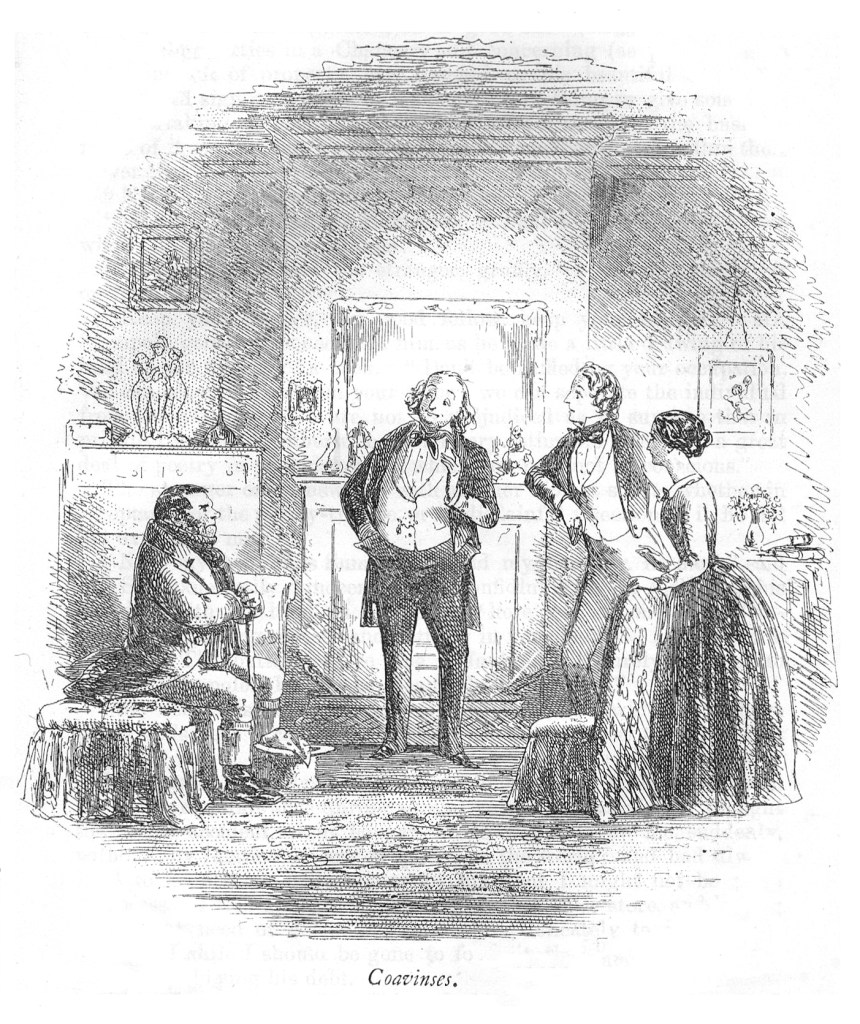

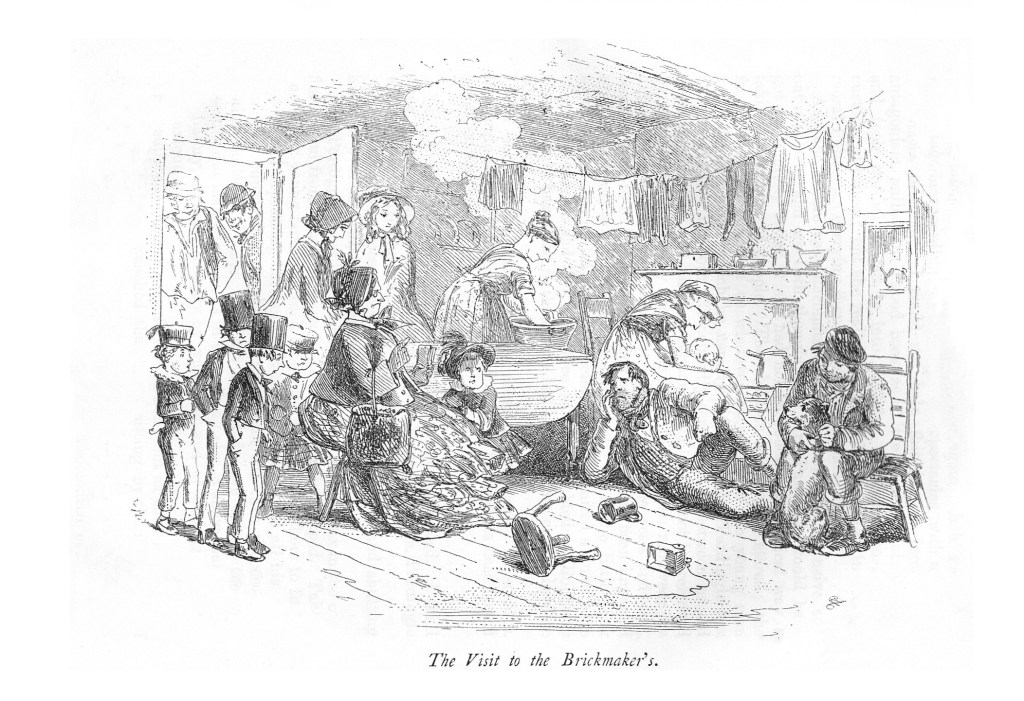

(Note: The below illustrations are by “Phiz,” Hablot Knight Browne, from the original edition, and have been downloaded from the marvelous Charles Dickens Illustrated Gallery. Thank you!)

“Fog everywhere…”

And “at the very heart of the fog, sits the Lord High Chancellor in his High Court of Chancery.” Cases drag on from year to year, unending, unresolved, bringing people to their graves or to the madhouse. The suit in hand is the “monument” of Chancery proceeding, Jarndyce & Jarndyce, that “scarecrow of a suit”–“perennially hopeless”–that has “in course of time, become so complicated that no man alive knows what it means.”

There is, however, something new in the case: two young claimants are coming to the Chancellor for permission to reside with their distant cousin—a man they do not know, also a claimant in the case—who has proposed himself as their guardian.

Meanwhile, a haughty and indifferent Lady Dedlock, who also has some claim in Jarndyce & Jarndyce, is fashionable and aloof, is preparing to leave a damp Lincolnshire for Paris with her husband, Sir Leicester Dedlock. Mr Tulkinghorn, the Dedlocks’ lawyer, comes to report on the Chancery proceedings. Lady Dedlock’s usual indifference is disturbed when she sees the handwriting on the the document that Tulkinghorn holds, written in “law-hand.” She, who never betrays emotion, becomes faint, and is assisted to leave the room.

Chapter 3 introduces us to Esther Summerson’s narrative, and her words suggest that she has been asked/encouraged to write of her involvement with the case. But we learn first of her unhappy childhood, of the godmother who raised her and never had a kind word for her; of how, when Esther was a young teenager, her godmother died, and a man she recognized—who turns out to be Mr Kenge from Kenge & Carboy’s law office—tells her that she has a patron in Mr Jarndyce, who has arranged for her to be sent to a school in Reading where governesses are trained. She is there at Greenleaf for six pleasant years, until she receives a letter from Mr Kenge that she can come to live with her guardian, Mr Jarndyce. Esther travels to London.

Once in London, Esther is introduced by Mr Kenge to a young clerk in the firm, Mr Guppy, as well as to the two wards in Jarndyce, the beautiful Miss Ada Clare and the handsome young man Mr Richard Carstone. Esther, Richard, and Ada are instant friends, and they prepare to make the journey to Mr Jarndyce’s residence, Bleak House. They encounter a flighty woman who hangs about Chancery, waiting the judgement on a long-drawn-out case.

On the way to Mr Jarndyce’s, the friends have had accommodations prepared for a stopover at the home of Mrs Jellyby, a long-distance philanthropist—who is encouraged by her other philanthropic friend, Mr Quale—who sees nothing nearer than the troubles in Africa. Mrs Jellyby makes her daughter, Caddy, transcribe endless letters in pursuit of her telescopic philanthropy, all while her own household is in complete disorder and her small children neglected. Esther and Ada become temporary surrogate mothers to the unfortunate little Peepy, who is constantly getting himself into scrapes. Before retiring for the night, the unfortunate Caddy comes unexpectedly into Esther’s room, confiding her anger and troubles to Esther, wishing she’d had someone like Esther to guide her. With her head on Esther’s lap, Caddy falls asleep.

The following day, the friends, with Caddy, encounter the flighty woman from Chancery again, Miss Flite. Miss Flite, who resides above Krook’s rag & bottle shop, invites them over to her apartment. (Mr Krook is often nicknamed the Chancellor, due to his knowledge of Jarndyce & Jarndyce & his having so many odds and ends and documents about his curiosity shop.) Krook tells them the harrowing story of Tom Jarndyce, who killed himself because of the never-ending case. In Miss Flite’s apartment, she has many birds in cages, all of whom will be released when Chancery finally makes a judgment on her case.

The friends journey forth to Bleak House, and are met by their new guardian, Mr Jarndyce, who has already requested that they meet him as though they’d already been long friends, with no words of thanks (which he cannot abide). They are introduced to the “child” Harold Skimpole, a middle-aged man constantly in debt who wants nothing more than to have no responsibility in the world. Skimpole relies on Mr Jarndyce’s charity to keep him in his state of freedom. But, unknown to Mr Jarndyce until after the fact, Esther and Richard are drawn into Mr Skimpole’s affairs when a man comes to collect a debt of Skimpole’s for just over 24 pounds—or he is to be held in custody at Coavinses. Richard and Esther pay it out of their own savings. Later, Jarndyce insists that they never do so again, as this is a habit of Skimpole’s.

Esther, who is immediately given the keys to Bleak House and is to be in charge of keeping things in order, is grateful to think of the fatherly care of Mr Jarndyce, and of the confidence shown in her so soon.

We return to Chesney Wold, the Lincolnshire home of the Dedlocks. The housekeeper, Mrs Rouncewell, who alludes to her dead soldier-son George, is taking several lawyers (among whom is Mr Guppy of Kenge & Carboy) on a tour of the home. Mr Guppy is struck by a portrait of a younger Lady Dedlock. Something about it is familiar…

Later, when Guppy leaves, Mrs Rouncewell tells the story of the Ghost’s Walk–a feature on the Dedlock grounds–to her grandson and the new maid, Rosa. The story involves the division between a husband and wife during the reign of King Charles I. Due to the haughty lady’s differing political opinion and her anger at her husband’s side–and her ensuing sabotage by laming the horses who were to have been used to ride out for the king—the husband, catching her in the deed, struggled with her and broke her hip. Though lamed, she was able afterwards to walk there on the terrace, and would walk up and down almost obsessively, and, refusing her husband’s help, predicted a dismal future for the Dedlock house:

“I will die here, where I have walked. And I will walk here, though I am in my grave. I will walk here, until the pride of this house is humbled. And when calamity, or when disgrace is coming to it, let the Dedlocks listen for my step!”

Back at Bleak House, Esther is given an introduction to the horrors of the Jarndyce case by Mr Jarndyce himself, in the “Growlery” (the room where he comes to vent when “the wind is in the east”). Esther helps Jarndyce attend to his correspondence, and Ada and Esther accompany one of his friend-philanthropists, Mrs Pardiggle, to some poor hovels in London. In one home, that of a bricklayer who is clearly violent and hates Mrs Pardiggle’s lecturing visits, Ada and Esther show compassion to the bricklayer’s wife, whose baby, so near to death, shortly dies.

Thought is given to Richard’s future prospects and the kind of career he’d like to have. The three friends are introduced to Jarndyce’s old friend, Mr Boythorn, a man of a huge laugh and boisterous personality, who, in spite of his huge voice and protestations (particularly about Sir Leicester, with who he has been in a long, hot struggle regarding rights of way in their properties), is so tame that a canary bird of his is often seen perching on his shoulder.

Mr Guppy, extravagantly dressed, pays an unexpected visit to Bleak House, and surprises Esther by a very eccentric declaration of his love and his desire to marry her, in one of the greatest proposals in literature.

“My present salary, Miss Summerson, at Kenge and Carboy’s, is two pound a week. When I first had the happiness of looking upon you, it was one fifteen, and had stood at that figure for a lengthened period. A rise of five has since taken place, and a further rise of five is guaranteed at the expiration of a term not exceeding twelve months from the present date. My mother has a little property, which takes the form of a small life annuity, upon which she lives in an independent though unassuming manner in the Old Street Road. She is eminently calculated for a mother-in-law. She never interferes, is all for peace, and her disposition easy. She has her failings — as who has not? — but I never knew her do it when company was present, at which time you may freely trust her with wines, spirits, or malt liquors. My own abode is lodgings at Penton Place, Pentonville. It is lowly, but airy, open at the back, and considered one of the ‘ealthiest outlets. Miss Summerson! In the mildest language, I adore you. Would you be so kind as to allow me (as I may say) to file a declaration — to make an offer!”

Guppy is declined, and Esther breaks down.

In London, Tulkinghorn pays a visit to the mild law stationer, Mr Snagsby, for information about who copied the affidavit that so struck Lady Dedlock, causing her recent uncharacteristic faintness. He informs him that is was done by Mr Nemo, who lives near Miss Flite, above Krook’s rag and bottle shop. When Tulkinghorn goes to pay him a visit, Nemo is discovered to be dead, and there is the scent of opium hanging about the room.

Krook is called in to witness to the corpse, and ends up hiding some papers that he finds among Nemo’s belongings. A doctor is fetched, and it looks as though Nemo had died about three hours previously, from opium overdose. An inquest is held, and among those bearing witness is a poor crossing sweeper boy who is called Jo, who knew Nemo to have been kind, sharing what little money he had with him.

When the Dedlocks return to Lincolnshire from Paris, Lady Dedlock is struck by the new young maid, Rosa, taking a fancy to her, and causing some envious mocking from the French maid, Hortense. That evening, Tulkinghorn brings his usual news to Sir Leicester, mostly about the dispute with Boythorn, but then mentions in a faux-offhand manner about having found the man who copied the affidavit that Lady Dedlock saw. He had died, either of purposeful or accidental overdose of opium.

Meanwhile, Richard, ever indecisive about his future career and plans (due, as Jarndyce thinks, to the interminable court case’s influence), he agrees to take up apprenticeship with the surgeon Mr Bayham Badger. (Whose wife, he is proud to say, has had two previous husbands of the most excellent character—Captain Swosser and Professor Dingo.) Esther, who has suffered in silence some unwelcome stalking from the obsessed Mr Guppy, then notices that Ada is troubled by something: Richard has just declared his love for Ada—something which does not surprise Esther greatly. Mr Jarndyce gives them his blessing, though Richard still has some work to do before they can think of marriage.

They all accompany Richard as his new career begins, and they also visit the Jellybys. Caddy confides to Esther, Ada, and Mr Jarndyce that she has been trying to improve herself, and has fallen in love with her deportment instructor, the young Prince Turveydrop. They also visit Miss Flite, and meet Mr Woodcourt, the young doctor who was present to confirm Nemo’s death. We learn that Jarndyce has been a hidden benefactor to Miss Flite, of funds which she thinks is coming from the Lord Chancellor.

Hearing that the man who had come to collect Skimpole’s debt, Mr Neckett, had died, leaving three young children on their own, Mr Jarndyce, accompanied by Ada and Esther, visits the children. He finds a young boy of about five, caring for an 18-month-old child, while their 13-year old sister, Charley, has gone out to do the washing to make some money for them all. Mr Jarndyce is moved by their situation. They also meet Mr Gridley, a neighbor who has been kind to the children, who has been angered by his own interminable Chancery case which has caused him such personal distress. Meanwhile, Jo the crossing sweeper, trying to make enough to have a temporary lodging at Tom-all-Alone’s, is requested by a lady in black–whose face is covered by a veil and who claims to be a servant–to show her the places where Mr Nemo lived, worked, and died. She is also shown the harrowingly neglected graveyard where he was buried. This mysterious woman gives Jo money for his troubles.

Discussion Wrap-Up (Weeks 1 & 2)

Miscellany & What We Loved: Audiobook Recommendations; Resources; Responses to the Introduction

Huge “thank you” to the appreciative comments about the Introduction to Bleak House, friends! Daniel, Rob, Lenny shared a number of insights about its helpfulness. Lenny wrote:

“Boze–a huge hurrah to both you and Rach for your superb introduction into this Mountain of a novel. The background materials, the various writings about London at Mid-century, the comments about the novel’s presentation of the interconnectedness of all things going on in the big city–really ring true and are so helpful for the reader going through the early parts of this hugely important novel.”

~Lenny H. comment

And, as we’re all eager for resources and recommendations, I’d like to give a shout-out to this fascinating resource that Chris shared with us, called “Esther’s Narrative”:

http://esthersnarrative.une.edu.au/

A huge “thank you” to Rob for his recommendation of the Miriam Margolyes audiobook, and for his current thoughts on his own version:

Daniel expresses our own thoughts about climbing the “mountain” that is Bleak House. He also lists the things from the introduction that struck him most forcefully, and I’ll keep the integrity of the list here:

And on that note, Bleak House was Daniel’s favorite Dickens novel in college:

Dickens’s “Writing Lab”: Characterization; “This Isn’t the Crowd Pleaser that was David Copperfield“

The Stationmaster considers Bleak House in relation to the rest of the Dickens canon:

Much of what we’re discussing this week–the reader response, the dual narration, etc–could be placed under the header of the “writing lab”; however, some of these had so much discussion involved that I wanted to keep them separate. But here, Stationmaster gives us some thoughts on Dickens’s characterization:

Lenny responds:

Lenny also had an intriguing idea about how Guppy might serve as a link between the two narrations:

Telescopic Philanthropy; How to Do Charity “Wrong”

In response to the Stationmaster’s post on Mrs Jellyby and Mr Skimpole, Jacquelyn shares her thoughts on a theme of interest to Dickens: “telescopic philanthropy.”

“Nothing in Dickens is By Accident”: Echoes of Ancient Battles in Jarndyce and Jarndyce

Rob, a big fan of Dickens’s less-well-known Christmas book, The Battle of Life, had a wonderful insight about the allusion to an ancient battle in connection to the interminable Chancery case. As Chris responded, “nothing in Dickens is by accident,” so I place the comment in full here:

The Reader in Dickens: Response to Esther & the Mystery-Narrator; the Reader as Detective

Lenny calls “anticipation and expectation” the “essence of the novel-reading experience” in response to Rob’s curiosity and enthoosymoosy to delve deeper into the mystery of the narration. As readers, Lenny writes, “we have to gather the clues, we become one of the chief detectives in this novel.”

But if the reader is a detective, we must also analyze our narrators–their reliability and relatability, and Esther is a divisive character. Lenny puts it this way:

“Esther is going to be the talk of the town, I think, and we readers are all going to weigh in in slightly and maybe even in hugely different ways about her. Definitely, though, she’s going to work as a kind of touchstone for the varieties of reader response that are gonna develop around this major character- in this voluminous novel.”

~Lenny H. comment

Earlier, Lenny commented on Boze’s introduction:

And more of Lenny’s responses to this controversial character:

The Stationmaster analyzes the experiment of the dual-narration. Though this could equally be placed under the “Writing Lab” category, I’m placing it here as part of our Esther dialogue:

In another comment, the Stationmaster compares Esther to Agnes Wickfield:

“While Agnes’s humility strikes me as less forced and less potentially annoying (probably she’s supposed to be less of a victim of childhood trauma than Esther and doesn’t have to narrate) than Esther’s, I feel like Dickens does a better job of showing Esther as a heroic character. We see her graciousness to Caddy Jellyby, her reaching out to the younger Jellybys, and her general helpfulness toward the other residents of Bleak House. With Agnes, it felt to me and to some other readers, I think, that we were told more about her kindness than we were shown.”

~Adaptation Stationmaster comment

Chris writes:

Jacquelyn is “strongly in the pro-Esther camp,” feeling deeply Esther’s traumatic background. Her responses simply make sense – she is “shaped by” these experiences:

The Stationmaster also draws attention to Esther’s “apologetic, uncomfortable tone”; she appears to be writing her “portion” at the request of another, or with someone’s encouragement. Who might this be? Could this person also be the other, unnamed narrator?

He then shares this intriguing idea:

Chris will be looking into some critical thoughts on this idea for us, and will report on what she finds.

Lenny, after analyzing the difficulties of seeing Esther as having both narrations, sums it up:

Still, there are questions. Lenny asks us to consider why Esther calls it “my portion”:

Rob loves the two narrative voices, and particularly Esther’s:

And again:

I am intrigued by the Esther-as-mystery-narrator, but think that, if the mystery narrator is someone we know, it is far likelier to be John Jarndyce:

Similarly, I discuss again the astounding opening chapter, and can see it as being penned by Jarndyce:

“Not only the evocative description of the ‘implacable November weather’ and the FOG — the Lord High Chancellor being at the heart of the fog — but the very descriptions of Chancery itself. So often in Dickens, the PLACE is an echo or an illustration of the interior reality. It is ‘dim’; the fog has little means of getting out; the stained glass windows ‘admit no light of day’. Members of Chancery are ‘tripping one another up on slippery precedents, groping knee-deep in technicalities,’ and the whole thing is compared to a ‘game’: ‘walls of words and making a pretence of equity with serious faces, as players might’. As to the conversation above (about the authorship of the omniscient narrative portions), I can certainly imagine Jarndyce writing THIS.”

~Rach M. comment

But Lenny asks: do we really need to identify a known narrator? Thoughts?

Word Spotlight: RESPONSIBILITY & DEBT; “Comic/Tragic Parental Neglect”; Am I My Brother’s Keeper? Who is My Neighbor?

In response to the Stationmaster, Lenny had written of Skimpole and Mrs Jellyby as “two extreme examples of comic/tragic parental neglect”:

Chris writes about what might be the key theme of the novel: responsibility. Whom are we responsible for?

Lenny responds:

Lenny also asks whether Richard and Ada might be in the “middle ground”:

“But what of the middle ground? Do we put Richard in that category. And perhaps Ada, too. They are both ‘takers’ in that they are living off their ‘guardian’–John–and they seem to give so little to the family’s well-being, but in these early chapters they don’t seem necessarily irresponsible. Although we can detect in Richard a tendency to procrastinate and not take life as seriously as we would like him to do. But he, like Ada, seems so sweet and likeable that we can’t entirely put them in the category of the irresponsibles…yet.”

~Lenny H. comment

I respond:

Chris, in response to Lenny’s questions about who is responsible to whom, who is in that middle-ground, and how the interconnectedness will play out, writes the following–a great way to end the discussion this week:

“I think it is part of Dickens’s plan to expose the muddle of the question(s) of who is responsible, how far does it go, how is it shared, when is it best left alone, where is the line between individual responsibility – societal responsibility – state responsibility, IS there a line? He’s making us think, and if that thinking changes how we behave, even if only toward ourselves though hopefully toward others as well, then ‘Bleak House’ is a success!”

~Chris M. comment

A Look-Ahead to Weeks 3 and 4 of Bleak House (27 June to 10 July, 2023)

This week & next, we’ll be reading Chapters 17-32, which constitute the monthly installments VI-X, published between August and December 1852. Feel free to comment below for your thoughts, or use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter.

If you’d like to read it online, you can find it at a number of sites such as Gutenberg.

I canNOT believe I didn’t mention this during the discussion the last 2 weeks, so I emphasized it in the chapter summaries: isn’t Mr Guppy’s proposal to Esther one of the BEST in literature?? 🤣🤣🤣

LikeLiked by 3 people

OMG–the poor little man. Such a little peacock!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hahaha 🤣 poor guy…it is truly one of the best-worst proposals ever 😂 right up there with Darcy and Collins!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Oh, it’s outstandingly cringeworthy. And Esther barely even attempts to pretty up her repulsion (then or later at the theatre) in the narrative!

LikeLiked by 3 people

Oh Lord, Mr. Collins. A truly Austenian Dickens’ character!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Greetings, Rach, Boze, and All Inimitables!

Such a deep, wide reflection on this remarkable work–with the bull’s eye issue being responsibility/debt.

It does seem that the “tapestry” of the human condition suggests that we are all related, connected, and therefore co-responsible.

At various times, we are “givers” and other times “takers” of goodness and

kindness. In our connections and co-responsibility lie our viability and capacity to live fully human lives.

And then there are the freeloaders . . . . Skimpole being the archetype and poster-child! Such folks shirk responsibility for others, although they might (like Skimpole) add relish . . . .

A few other considerations:

1. “so complicated that no man alive knows what it means”: The “fog” and never-ending encircling of the Jarndyce versus Jarndyce case takes Dickensian circumlocution to a new and dizzying level!

NOTE: “The term Circumlocution Office was first coined by Charles Dickens in his novel ‘Little Dorrit’ to describe, and parody, the government bureaucracy of the day.”

2. Guppy’s proposal to Esther: Truly one of the “greatest” (tongue firmly in cheek) proposals in literature. I chuckled at the prospect of Esther, when alone after this strange proposal, laughing . . . before crying.

3. Jacquelyn on telescopic philanthropy: Thanks much to you, Jacquelyn, for your thoughts about this troubling phenomenon. One thought that occurred to me is that women such as Mrs. Jellyby and Mrs. Pardiggle were women who aspired to greater influence on society than they could exert as mothers. This possible chafing at their lack of access to positions of power and influence might have been channeled into their skewed attempts to benefit those at a distance while so evidently disregarding their nearest and dearest.

4. Rob’s insight about the battle-field and the case of Jarndyce versus Jarndyce: Rob, this is so very illuminating. I can only imagine that Dickens’ brilliant, searching mind detected overtones and undertones of theme, character, and plot everywhere–including the historical battle and battlefield as parallels and foils to the “spoils” of a legal dispute. Thank you!!!

5. ‘We become one of the chief detectives in this novel”: GREAT way to frame our roles as active and eager readers. We are amassing clues to “solve” the mysteries of this universe of Bleak House. We are “Buckets on the case”! Excellent!

Chris, many thanks for your always deepening resources, including regarding Esther as narrator.

Blessings,

Daniel

LikeLiked by 3 people

I love this quote from Chapter 17 but part of it confuses me.

“Richard very often came to see us while we remained in London (though he soon failed in his letter-writing), and with his quick abilities, his good spirits, his good temper, his gaiety and freshness, was always delightful. But though I liked him more and more the better I knew him, I still felt more and more how much it was to be regretted that he had been educated in no habits of application and concentration. The system which had addressed him in exactly the same manner as it had addressed hundreds of other boys, all varying in character and capacity, had enabled him to dash through his tasks, always with fair credit and often with distinction, but in a fitful, dazzling way that had confirmed his reliance on those very qualities in himself which it had been most desirable to direct and train. They were good qualities, without which no high place can be meritoriously won, but like fire and water, though excellent servants, they were very bad masters. If they had been under Richard’s direction, they would have been his friends; but Richard being under their direction, they became his enemies.”

What are the “good qualities” to which Esther refers? Are they being able to do things “with fair credit and often with distinction?” Or being able to do things “in a fitful dazzling way?” I can’t imagine Dickens or Esther really believing that “no high place can be meritoriously won” without those qualities. So many of Dickens’s books celebrate the heroism of humble, non-showy characters, like Esther herself or Mr. Snagsby in his kindness to Jo.

Skimpole and Boythorn are one of the best comedy teams in Dickens if you ask me. We should make a list of the best Dickensian double acts.

Chadband is one of the most, if not the most, awesomely annoying characters Dickens ever wrote! I can’t imagine listening to an entire speech by him without screaming or chucking something at his head. (I write this to praise Dickens BTW.)

I love the hilarious double meaning of this line. “To become a Guppy is the object of (Young Smallweed’s) ambition.”

LikeLiked by 3 people

I may project too much onto him, but I’ve always taken Richard’s problem here to be one that’s familiar to many — he has been intelligent and quick enough to succeed at the tasks put before him thus far without having to put in too much effort. This is indeed an asset in itself — fulfilling the “high place […] meritoriously won” requirement — but of course it can’t stand alone. What seems a virtue in a school setting, or when engaging in anything for which one already has a natural talent, can also limit one’s ability at a young age to master the discipline of gutting it out through more challenging work. In Richard’s case, and in another of the book’s treatments of childhood neglect, no one especially cared so long as he proved a successful cog in the school system.

Esther’s a great observer of this fatal flaw. While Jarndyce likes to blame the suit, I think she’s correct that its roots go deeper, as in another key passage in chapter 13: “He had been eight years at a public school, and had learnt, I understood, to make Latin Verses of several sorts, in the most admirable manner. But I never heard that it had been anybody’s business to find out what his natural bent was, or where his failings lay, or to adapt any kind of knowledge to him. [….] I did doubt whether Richard would not have profited by some one studying him a little, instead of his studying them quite so much.”

LikeLiked by 4 people

Jacquelyn: Your final paragraph is SO right on, here. Esther IS a great observer of this “fatal flaw” in Richard. Her acute observations about him and his weaknesses begin so very early in the novel and just ring increasingly true as the narrative advances. She, Mr Jarndyce, and finally Ada later on, first suggest and then plead with Richard to avoid getting involved with the suit. But I believe there is this sort of arrogant, “I-know-better-myself” side that seems to step in (obviously part of his shadow that he can’t control) and just controls him mercilessly–to the extent that he begins to turn on his benefactor, himself.

There are signs of this weakness early on in the novel when he seems to be sort of a playful and not altogether with it character. At that time, we see him as a kind of breath of fresh air in a novel which is filled with–both literally and figuratively–fog, tainted air, and tainted and predatory characters. But his descent is fairly gradual until finally he loses his way and the devil-may-care side of his personality which seemed so vibrant and fun degenerates into a self-destructive and ultimately destructive force.

So, as the novel presents the increasingly fearful responses of his closest companions and friends to his growing abhorrent behavior, we readers stand by feeling just as frantically as they–almost to the point that we want to jump into the narrative and shake this young man back into his senses.

Jarndyce might put the blame on the Chancery suit, but he really seems to be shirking some of his responsibility toward Richard in this regard. He exhibits just too much enabling behavior toward his ward. Somehow, we/I want a more profound intervention in this man’s behavior. But how to do it is the question.

Whether, then, Jacquelyn, it be childhood neglect, some fatal flaw in Richard’s mental make up, or a combination of the two, Dickens has certainly provided us with an interesting psychological study.

LikeLiked by 3 people

There was something I wanted to say about Mr. Gridley last week or so, but I forgot. Since Gridley is in these two weeks’ reading too, I might as well say it now. Ordinarily in Bleak House and elsewhere, Dickens writes about characters who take themselves very seriously but whom the reader is supposed to take as jokes. (I was going to give a list but there are too many characters like that in this book.) With Mr. Gridley, he does kind of the opposite. He shows us a character whom society treats as a joke but whom we should take seriously.

I also forgot to bring up this about Lady Dedlock and Rosa (who also figure in this week’s reading.) I wonder if Lady Dedlock telling Rosa to take care people don’t spoil her with flattery because of her beauty is meant to imply that Lady Dedlock’s scandalous relationship in the past was the result of such flattery. But that might make “Nemo” less sympathetic than I think Dickens means him to be. (Sorry if I’m spoiling anything, but I feel like that much is pretty obvious by now.)

I noticed that in Chapter 17, John Jarndyce calls Esther by her given name twice instead of “Dame Durden” or “Little Woman.” I wonder if that means anything.

Both Great-Grandpa Smallweed and Uriah Heep are the result of charitable schools. Dickens seems to have been very disgusted with those schools, but given how he monstrous he makes their pupils, could he be accused of victim blaming? Could these characters be seen as antisemitic stereotypes like Fagin? (Jewish people might well have attended charitable schools and Judith and Bartholomew are vaguely biblical sounding names.)

It occurred to me on this read that Judith Smallweed can be seen as something of a foil to Esther. Check out this description of her.

“Judy never owned a doll, never heard of Cinderella, never played at any game. She once or twice fell into children’s company when she was about ten years old, but the children couldn’t get on with Judy, and Judy couldn’t get on with them. She seemed like an animal of another species, and there was instinctive repugnance on both sides.”

We learn in the first chapter Esther narrates that she had a doll growing up and she compares herself to a fairy tale princess. She also regrets that she didn’t have closer friendships with other children in her youth and enjoys their company in her adulthood. The way she treats Charley Neckett certainly contrasts with how Judy treats her.

I already wrote about this in my essay about Bleak House (That’s what Rachel calls it anyway; I didn’t really follow the rules of essay writing with it) but I love the scene of Caddy Jellyby telling her mother about her engagement. I love the depth it adds to her character. As much as she hates her mother, on some level, she wants her mother to care about her, even get angry with her rather than be indifferent. There’s something so poignant about that to me.

I’m not particularly a fan of J. R. R. Tolkien but recently my family was watching a movie adaptation of The Lord of the Rings and it occurred to me that the Ring in that story is much like the case of Jarndyce and Jarndyce in its evil effect on everyone. You could even say that Richard Carstone corresponds to Boromir and John Jarndyce to Gandalf. OK, not really, but I thought any Dickens fans reading this who are also Tolkien fans might find the idea amusing.

As tragic a character as Jo is, this line about him hilariously sums up our feelings toward Chadband. He “would rather run away from him for an hour than hear him talk for five minutes.”

I love Mrs. Bagnet! But she arguably doesn’t fit in with this book’s themes. Every other example of a marriage where the wife is in charge or has a more forceful personality than her husband is a highly negative one. (cf. The Snagsbys. The Jellybys. The Pardiggles. I guess the Chadbands are pretty egalitarian in their awfulness.) By contrast, Dickens seems to totally approve of Mrs. Bagnet as the decision maker for her family and so do her husband and children.

It fascinates me how relatively neutral Dickens is in his portrayal of the class conflict between Sir Leicester Dedlock and Mr. Rouncewell. Well, he’s relative by Dickensian standards, that is. It’s true that Dickens has some laughs at the expense of Sir Leicester’s conservatism. (“Sir Leicester very magnificent again at the notion of Mrs. Rouncewell being spirited off from her natural home to end her days with an ironmaster.” Yeah, retiring to live with her millionaire son, that would sure be bad for her.) But while Mr. Rouncewell seems like a decent man, Dickens doesn’t portray him as particularly saintly or try to get the reader to root for him against the Dedlocks. (If you haven’t read the book before, do not read the rest of this paragraph, I beg you!) Most notably, while Mr. Rouncewell never becomes unlikable per se, neither does he become as sympathetic and even admirable as Sir Leicester is by the end of the book.

LikeLiked by 4 people

I love these character analyses, Stationmaster!! Some of these quote are just fantastic– Judy as foil to Esther, & the one on Chadband! 😂 Chadband absolutely cracks me up every time. I feel like Boze & I are going to start speaking in Chadbandisms–e.g. “what is this that we now behold spread before us? Refreshment. Do we need refreshment, my friends? Because we are but mortal, because we are but sinful, because we are but of the earth, because we are not of the air. Can we fly, my friends? We cannot. Why can we not fly, my friends?” 😂 and talking about “Terewth”!

LikeLiked by 3 people

Nice work, here, Stationmaster, on the Judith/Esther foil set up. Moreover, one notices how how deeply this comparison-contrast goes, though, as they were both the victims of circumstance at their very young ages, but Esther was still the beneficiary of more human and humane treatment than Judith was, even at the hands of her aunt. Moreover, Esther had the huge benefit of attending the Greenleaf finishing school whereas I presume Judith was left to her own devices at the mercy of Smallweed senior and his poor belittled wife during her formative years.

Man, the more I write about these various characters in BH, I realize how astute the psychological portraits ARE that Dickens has drawn up!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I listened to the Stephen Fry episode of the “Charles Dickens: A Brain on Fire” podcast, and I’d really recommend it. He talks about how the novel is asking, What is guilt, and what is innocence, and Who is guilty and who is innocent. And who should be alive, and who should be dead – given the constant interplay between characters who supposedly should be dead/should never have been born coming to life (Esther) and those who are very much alive having to die.

And I also note the constant pairing we get in Bleak House: the child who should not be (Esther, Caddy’s child, the brickmaker child who turns out to play a crucial part in the plot), the prodigal son (George Rouncewell, Captain Hawden), the relentless investigator hunting down his quarry (Mr Tulkinghorn, Mr Bucket), the patron (Sir Lester, Mr Jarndyce, the Lord Chancellor), the courtiers (Miss Flyte, Volumnia), the mother figures (Miss Barbary, Mrs Rachael, Mrs Rouncewell, Mrs Bagnet). The parallel roles occur again and again, while the characters diverge utterly. The mirroring being most apparent of all between Esther and Lady Dedlock.

– And Stationmaster, yes brilliant, of course Judy is another foil to Esther.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Wasn’t that a good ep of Brain on Fire, Lucy? And I agree with you — I LOVE Dickens’ doubling…but I hadn’t thought it through in relation to BH as you have here! YES!

LikeLiked by 2 people

The pairing and doubling and contrasting of so many things with others is a fascinating feature of this novel.

This rightly belongs in the tail end of last weeks section but as it plays out through the novel there’s no shame in being a little behindhand with it… 😊

There is a significant pairing both of Richard Carstone and Caddy Jellyby individually and within their prospective engagements to Ada and Prince Turveydrop.

In Chapter 13 when Jarndyce finds out about Richard and Ada’s hopes he makes Richard promise to work hard for Ada’s sake:

Now we lift our eyes up and look hopefully at the distance! Rick, the world is before you; and it is most probable that as you enter it, so it will receive you. Trust in nothing but in Providence and your own efforts. Never separate the two, like the heathen waggoner. Constancy in love is a good thing, but it means nothing, and is nothing, without constancy in every kind of effort. If you had the abilities of all the great men, past and present, you could do nothing well without sincerely meaning it and setting about it. If you entertain the supposition that any real success, in great things or in small, ever was or could be, ever will or can be, wrested from Fortune by fits and starts, leave that wrong idea here or leave your cousin Ada here. (BH—13)

His advice here very strongly echoes David Copperfield’s wholesome sentiment:

I do not hold one natural gift, I dare say, that I have not abused. My meaning simply is, that whatever I have tried to do in life, I have tried with all my heart to do well; that whatever I have devoted myself to, I have devoted myself to completely; that in great aims and in small, I have always been thoroughly in earnest. I have never believed it possible that any natural or improved ability can claim immunity from the companionship of the steady, plain, hard-working qualities, and hope to gain its end. There is no such thing as such fulfilment on this earth. Some happy talent, and some fortunate opportunity, may form the two sides of the ladder on which some men mount, but the rounds of that ladder must be made of stuff to stand wear and tear; and there is no substitute for thorough-going, ardent, and sincere earnestness. (DC—42)

In Chapter 14 Caddy tells Esther of her secret engagement to Prince Turveydrop and says of herself ‘I only wish I had been better brought up and was likely to make him a better wife’

She then becomes the embodiment of the earnestness and constancy in effort recommended by Jarndyce and championed by Copperfield by revealing that she has been visiting Miss Flite to learn the rudiments of good-housekeeping:

You know what a house ours is. It’s of no use my trying to learn anything that it would be useful for Prince’s wife to know in OUR house. We live in such a state of muddle that it’s impossible, and I have only been more disheartened whenever I have tried. So I get a little practice with—who do you think? Poor Miss Flite! Early in the morning I help her to tidy her room and clean her birds, and I make her cup of coffee for her (of course she taught me), and I have learnt to make it so well that Prince says it’s the very best coffee he ever tasted, and would quite delight old Mr. Turveydrop, who is very particular indeed about his coffee. I can make little puddings too; and I know how to buy neck of mutton, and tea, and sugar, and butter, and a good many housekeeping things. I am not clever at my needle, yet…but perhaps I shall improve, and since I have been engaged to Prince and have been doing all this, I have felt better-tempered, I hope, and more forgiving to Ma.</em) (BH—14)

I have a feeling that I’m gonna become a big fan of Caddy Jellyby. I certainly have a feeling that she will perhaps enjoy more success with her efforts than Richard seems likely to make

LikeLiked by 2 people

I enjoy the character dynamics between Richard, Esther and Ada in Chapter 17 with Ada being biased in Richard’s favor and Esther stuck playing bad cop.

I have a funny story about when I first read Bleak House, but it’s rather dirty. I hope people aren’t offended. (If this part of the comment is inappropriate, is there way Rachel and Boze can edit it out and keep the rest?) On my first read, I was getting bored and was starting to skim the stuff with the Turveydrops and the Jellybys since I could tell it was filler. Then this out-of-context statement from Mr. Turveydrop jumped out at me. “The sex stimulates us and rewards us.” I did a doubletake and wondered what kind of dancing school he was running. LOL.

I wonder if Lady Dedlock telling Guppy he had better sit down in Chapter 29 right after he says he knows Mr. Tulkinghorn is significant. Was he subtly threatening her? Or did she just tell him that because it was obvious he was going to make a very long speech? In any case, the tension in that scene, with him having to tell her he knows she has an illegitimate child without actually saying it, is great.

In my previous comment, I implied that Mr. Pardiggle was one of the novel’s henpecked husbands but that’s not what our brief glimpse of him in Chapter 30 indicates.

“Mr. and Mrs. Pardiggle were of the party—Mr. Pardiggle, an obstinate-looking man with a large waistcoat and stubbly hair, who was always talking in a loud bass voice about his mite, or Mrs. Pardiggle’s mite, or their five boys’ mites.”

This makes him sound like he has just as much of a forceful (and unpleasant) personality as his wife. It still seems like she’s the one calling the shots in the family though as he’s apparently complaining about her making him and their sons donate all their money to various causes. Or could it be that he agrees with her and is bragging? It seems like Dickens originally intended for Mr. Pardiggle to be just like Mr. Jellyby but then decided against it, feeling that would be boring and repetitive.

I’m not particularly familiar with smallpox. Was it a disease to which the young were mainly vulnerable? I noticed that Esther is very worried about infecting Ada with it but she doesn’t seem to show the same caution toward Jarndyce.

Krook’s death is one of the wildest demises in Dickens. I’m not sure if I love it ironically or just love it.

LikeLiked by 3 people

On Krook’s spontaneous combustion: I’m not sure yet quite *why* I love the Krook and Smallweed scenes more than any other in BH, more even than the beloved George. But I do think those are some of the most wonderful visions ever. I can’t account for it yet: I’ll try and work it out. Why should one love the grotesque so much. Anyway, with you there, Stationmaster, and not ironically, either.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Stationmaster: The Guppy Lady Dedlock confrontations are always fraught with tension, it seems to me, because he is decidedly trying to ferret out from her–and also directly challenging her about– the truth regarding her resemblance to Esther and herself. He’s slowly but surely closing in on the secret of Esther’s birth and she (Lady Dedlock) is both desperately afraid of what he knows but haughtily angry that such a little twit of a law clerk should be on to her.

So a couple of things (if not more) are at work during these discussions. One has to do with class. She resents that this little man who is SO inferior to her socially should be in his passive-aggressive manner suggestively questioning her, and he, in his egalitarian snooping strives to undercut her upper class snootiness with his searching and prodding questionings. There is definitely a battle involving class consciousness going on here!

On the other hand, the undercurrent of fear that Lady Dedlock feels (shows?) goes beyond these class distinctions because she knows the truth about her relationship with “Nemo” is being found out by Guppy. And he realizes very quickly that he is on the right track. The tension, then, that arises out of these dialogues becomes palpable and also somewhat disconcerting for me, the reader. Why must Guppy and Tulkinghorn (later) be so darned nasty about seeking what becomes the “big reveal” in the novel?

You see, my sympathies fall with Lady Dedlock in this novel!

LikeLiked by 1 person

The smallpox: I think the point is that Esther regards Ada as young and lovely and with her life before her. If you survived it, the pox scars on the face were regarded as particularly awful for young women and girls – their face their only fortune. But you’re right, she doesn’t mention Jarndyce as needing protection. And there’s no fear expressed ever of Woodcourt getting it.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Hence (it being understood as a worse fate for a young woman) Esther’s going on, and on, about her own looks. I suppose it could be regarded as meaning social, if not literal, death.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I assume that since Woodcourt is a surgeon, everyone’s just resigned to him risking smallpox.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Part of the sex role dispensation? For once, counting against someone male.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is entirely possible that as a surgeon/doctor Woodcourt may have been innoculated against smallpox. Edward Jenner’s initial discoveries concerning the cowpox virus conferring immunity to smallpox were 1796

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yet, Lucy, Esther is so selfless about “handling” all of this smallpox infection–as Jo carries it to Bleak House, infecting both Charley and Esther, herself. All along, it seems to me, that Esther is always thinking about the others involved in this contagion, how to bring THEM through it, not heeding the possibilities that there is a real good chance she, too, will be infected. Of course, she does inevitably acquire the disease…. But even here, mindful that she will be scarred by the disease, her FIRST thoughts go to ADA–and how to keep her both from catching the disease and then not to allow her to see how the disease has destroyed her (Esther’s) physical beauty. She’s worried most, then, about these two factors that would shatter Ada physically and psychologically.

Yes, Esther will suffer from what the pox has done to her beauty, but her taking the high road through all of this calamity just cements, in my mind, her heroine status! And her behavior through this particular siege is symbolic of her courage. Thus, She is really quite some warrior through the entire novel, I believe, yet she still portrays in her actions and thoughts… hesitations, weaknesses, self-doubts, etc… her innate humanity.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rob: I want to go back to your wonderful and thoughtful earlier contrast-comparison of Richard and Caddy, where you speak of “the significant pairing” of these two characters. The ideas you present are so complex and interesting that I thought I’d try to make some sense of them in the context of some of the earlier remarks about the novel’s themes in the first couple of weeks of our BH discussion. I see them as operating under the umbrella of what Chris spoke of earlier, the idea of responsibility vs. irresponsibility. Obviously, Caddy, here, become the “responsible” character whereas Richard becomes the character who abdicates responsibility. But what a crazy irony the novel presents us with as it’s Richard who gets advice again and again from both Jarndyce (his guardian) and Esther, and it’s advice given with such love and caring and rationality, but he just can’t quite connect the dots and settle down to take it and make his way through the world as a productive individual. The role models are there–especially with the positive and beneficial work of Esther who runs with great efficiency the Jarndyce household. She’s a wonderful illustration for Richard to follow.

And what a contrast with Caddy who, with ALL the negative role modeling and negative advice (or lack thereof) from her mother, becomes just the opposite of Richard. The things she does for Miss Flite are just so precious and caring and loving as here she seems to be serving a kind of industrious apprenticeship leading up to her relationship and marriage to Turveydrop Jr. Kudos to Caddy and her hugely courageous move to take herself out of her dead end family situation, learn how to make a life that is both productive and fulfilling, and which seems to beat all the odds against her.

On the other hand, we have Richard–who has everything going for him–yet just takes the opposite tack and makes a total hash out of his life to the detriment of both himself and the relationship he has with Ada.

But then we ask why, why are these things so? And the novel really doesn’t help us there, I think, but just points out that out of the blue these things and character behaviors “happen.” And so, I think that this phenomenon makes itself felt with so many of the characters and situations in BH. How, for example, does one account for the character of Skimpole and his aberrant philosophy of life and its strange and obnoxious behaviors or the sad but thoughtful and caring conduct of Jo when he visits the graveyard with Lady Dedlock. Here’s a boy who constantly says he knows nothing–but somehow knows how to do the right thing?

Perhaps this theme/idea runs through the Dickens’ novels pell-mell and I am just now getting acquainted with it. But it sure is present big time in BH!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This certainly has continued to play out over this section. It seems that wherever there is a discussion about Richard’s future/career etc then Caddy appears shortly afterwards – if it be only to deliver Woodcourt’s flowers 🙂 Then later as Esther and Richard discuss the same, Esther is on her way to meet Caddy, who wants assistance with regard to HER future.

But this is just one connection/pairing in a novel that seems jam packed with such connections. What an extraordinary texture this novel has, eh? 🙂

“Then,” pursued Richard, “it’s monotonous, and to-day is too like yesterday, and to-morrow is too like to-day.”

“But I am afraid,” said I, “this is an objection to all kinds of application—to life itself, except under some very uncommon circumstances.” (Chapter 18)

LikeLike

Regarding new characters in relation to old ones, I find it interesting how Sir Leicester’s cousins are so similar to Richard: “ladies and gentlemen of various ages and capacities; the major part, amiable and sensible, and likely to have done well enough in life if they could have overcome their cousinship; as it is, they are almost all a little worsted by it, and lounge in purposeless and listless paths, and seem to be quite as much at a loss how to dispose of themselves, as anybody else can be how to dispose of them.” (Ch 28)

LikeLiked by 2 people

I haven’t quite gotten through everyone’s thought provoking posts – such great conversations going on here! Here are my thoughts on the first half of our current section.

I like the way Dickens the Writer fashions Inspector Bucket “with his forefinger and his confidential manner, impossible to be evaded or declined” (Ch 25) – as illustrated the emphasis of the word “YOU” to show Bucket increasingly, calmly, but persuasively and pointedly (like his finger), working on Mr Snagsby in Ch 22 to cajole him into accompanying the Inspector into Tom-All-Alone’s to find Jo:

‘You’re a man of the world, you know, and a man of business, and a man of sense. That’s what YOU are.”

and then to persuade Mr Snagsby to keep quiet about what transpires in Tulkinghorn’s office with Jo and Hortense:

“You see, Mr Snagsby, . . . what I like in you, is, that you’re a man it’s of no use pumping; that’s what you are. When you know you have done a right thing, you put it away, and it’s done with and gone, and there’s an end of it. That’s what YOU do.”

Bucket emphasizes just the right word, in just the right tone of voice, with the just right amount of flattery and suggestion to confuse Snagsby into compliance, into believing his is the way he (Snagsby) would, of course, behave. He uses the same tactic with Mr George in Ch 24 with some success, and tries it with Mr Gridley. But poor Gridley’s heart has finally broken and he can no longer be persuaded to anything.

Gridley’s sad life and death, one would think, should be a graphic and sobering example for Richard. But whether Richard grasps the similarity between Gridley’s experience with Jarndyce and Jarndyce and his own inclinations toward the suit – as Esther suggests in her final paragraph of Ch 25 – and if his absence in Ireland with his regiment can cure him of his growing obsession with it remains to be seen.

Richard’s awareness that his “unsettled” state is due to the unsettled state of Jarndyce and Jarndyce makes his growing obsession with it even the more troubling. One wonders how he would be if it were settled – would he be able to settle down or would he still “leave everything [he] undertook, unfinished, [and] find it hard to apply [himself] to anything”. (Ch 23)

Mrs Snagsby takes the meddling, shrewish wife to another level. Following in the footsteps of Susan Weller and Mrs Varden, Mrs Snagsby has her preacher, Mr Chadbrand, to mis-direct her efforts and feed her suspicions. Mrs Snagsby seems to be more dangerous and less humorous than either Mrs Weller or Mrs Varden, and one fears for Mr Snagsby who seems much less capable of mastering his “little woman” than either Tony Weller or Gabriel Varden.

A word regarding Mr Jarndyce – I really like him, but I question his judgment mainly because of his liking Mrs Jellyby and toleration of Mr Skimpole. I’m wondering what it is about these two that keeps Mr Jarndyce patronizing them. The more I get to know them the less likable they become. Mrs Jellyby’s refusal to see what’s right in front of her is sad and perhaps clinically diagnosable as some sort of depression because she seems to be unaware of her condition. Perhaps she is not unaware but just selectively blind. Mr Skimpole, however, is completely aware of what he’s doing and his protestations seems to me a slap in the face of any thinking person – he’s basically saying, as long as you allow me to take advantage of you I will. Whatever he offers in terms of good company or art appreciation is not quite enough in my estimation to repay the generous generosity of Mr Jarndyce.

There is a similarity between Mr Guppy’s proposal of marriage to Esther and Hortense’s offer to be Esther’s maid.

Mr Guppy says: “Blest with your hand, what means might I not find of advancing your interests and pushing your fortunes! What might I not get to know, nearly concerning you? I know nothing now, certainly; but what MIGHT I not if I had your confidence, and you set me on?” (Ch 9, emphasis in original)

Hortense says: “Receive me as your domestic, and I will serve you well. I will do more for you than you figure to yourself now. Chut! Mademoiselle, I will—no matter, I will do my utmost possible in all things. If you accept my service, you will not repent it. Mademoiselle, you will not repent it, and I will serve you well. You don’t know how well!” (Ch 23)

These two seem know something to Esther’s advantage – or disadvantage – or perhaps it is more correct to say they seem to know something about Esther that they can or wish to use to THEIR OWN advantage.

*

LikeLiked by 2 people

I hadn’t considered the possibility that Mrs. Jarndyce is clinically depressed, and she turns to social work as a way to cope. That makes her more sympathetic. Actually, on reflection, maybe it makes her less sympathetic since her motivations for being so involved with her causes are then entirely selfish.

The reason I hadn’t considered the idea is that Mrs. Jellyby seems so cheerful and that’s not how we expect depressed people to come across, but her cheeriness could be a mask. (I’m not a psychiatrist or anything, so I wouldn’t be able to speak with authority on the subject.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I meant to write Mrs. Jellyby in the first paragraph, not Mrs. Jarndyce.

LikeLike

Chris: You touch on so many issues and characters, here, so that it’s almost as though you’ve echoed, indirectly, the statement that Stationmaster makes below about the novel’s throwing at its readers SO many characters so quickly. There is something so overwhelming in its early stages that I, at least find myself constantly rereading passages to keep up with all the details about character and events that Dickens the writer presents us with. Like you, I find myself constantly thinking about and then rethinking about Mr. Jarndyce’s relation to and acceptance of Mrs. Jellyby and Skimpole because their presentation comes at us so quickly and so strangely. Who ARE these people and why does Jarndyce treat them almost as though they are part of his extended family. And just as we are trying to figure them out and their relationship to Jarndyce, we are off to the races to more characters and more strange situations. Enter Guppy and all that HE represents, and then Bucket and HIS machinations, and then Snagby and HIS marriage situation, not to mention Lady Dedlock, her entourage, and the entrance of Mr. Tulkinghorn and his seemingly important status vis-a-vis the Dedlocks, and then here is the everpresent Mr. Guppy…and on and on and on!

Oh boy,so much to digest, so much to keep track of, so much to try to understand, so many connections to make, secrets to make sense out of and so forth. So like you, we are often puzzled about relationships we don’t understand, characters and their activities, their obsessions, their functions in the narrative, what they mean, how we should see them, relate to them, gauge their importance to the larger scheme or schemes of the novel.

No wonder we are perplexed , then, about so much that is going on in this behemoth of a novel because we as readers are CONSTANTLY involved in a huge juggling act that just won’t seem to subside. All the plots, all the characters–they represent what seem to be a billion balls in the air that we try to catch and keep in motion throughout our reading experience….

OMG!

Kudos, then, to Stationmaster who has reread this novel many times and is now getting a sense of what it all means! For the first time reader, though, the experience is a pretty tough go and involves a lot of persistence and mental gymnastics to keep the novel’s meaning or meanings in some kind of reasonable perspective.

That’s why this reading group is so helpful, as we try together to sort out the complexities of this great novel!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderfully expressed, Lenny.

I think at this point of the novel we are *meant to* have more questions than answers and to ‘juggle’ our perplexities in trying to fathom the mysteries beneath the extensive surface of the novel.

I feel we stand almost stunned into the same condition as Mr Snagsby (coughing our coughs of great perplexity) finds himself:

Mr. Snagsby cannot make out what it is that he has had to do with. Something is wrong somewhere, but what something, what may come of it, to whom, when, and from which unthought of and unheard of quarter is the puzzle of his life. His remote impressions of the robes and coronets, the stars and garters, that sparkle through the surface-dust of Mr. Tulkinghorn’s chambers; his veneration for the mysteries presided over by that best and closest of his customers, whom all the Inns of Court, all Chancery Lane, and all the legal neighbourhood agree to hold in awe; his remembrance of Detective Mr. Bucket with his forefinger and his confidential manner, impossible to be evaded or declined, persuade him that he is a party to some dangerous secret without knowing what it is. And it is the fearful peculiarity of this condition that, at any hour of his daily life, at any opening of the shop-door, at any pull of the bell, at any entrance of a messenger, or any delivery of a letter, the secret may take air and fire, explode, and blow up—Mr. Bucket only knows whom. (Chapter 25 — Mr Snagsby Sees It All)

This firmly persuades me that we are entitled to feel a little over-whelmed by the mystery of it all at this point of the reading. Hoping that Mr Bucket will help us to see it all as we move on 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

I remember when I read Bleak House for the first time, the reading for these two weeks was the part I struggled through and skimmed over the most. The story already had a lot of characters and in these 16 chapters, Dickens introduces Mrs. Woodcourt, Mr. and Mrs. Chadband, Tony Jobling, all the Smallweeds, Mr. George, Phil Squod, Inspector Bucket, all the Bagnets, Volumnia Dedlock and Mrs. Rouncewell’s son. Phew! It’s only after reading the book several times and memorizing what role they all play in the plot that I feel like I can just relax and enjoy the greatness of all the characterizations.

LikeLiked by 2 people

This almost sums up my exact experience with this section when I first went through it (I was listening to the Miriam Margolyes audio version) I am not quite through the full section yet on my more detailed slower read of it, but yes, there is a host of new faces and new information all of a sudden thrown at us! It bears a re-read as there is an amazing amount of detail in there (as there is everywhere in this epic novel!)

LikeLiked by 1 person

With regard to our reading section for these two weeks having introduced an abundance of new characters and offshoots of plot, may I offer a brief analogy..

Supposing the novel were a house (make it a bleak one if you like) and supposing a character or character group were a ‘room’ and supposing the intricacies and twists of plot were staircases and corridors…

It was one of those delightfully irregular houses where you go up and down steps out of one room into another, and where you come upon more rooms when you think you have seen all there are, and where there is a bountiful provision of little halls and passages, and where you find still older cottage-rooms in unexpected places with lattice windows and green growth pressing through them…

(going) out at the door by which you had entered it, and turned up a few crooked steps that branched off in an unexpected manner from the stairs, you lost yourself in passages, with mangles in them, and three-cornered tables, and a native Hindu chair, which was also a sofa, a box, and a bedstead, and looked in every form something between a bamboo skeleton and a great bird-cage, and had been brought from India nobody knew by whom or when…

Out of that you came into another passage, where there were back-stairs and where you could hear the horses being rubbed down outside the stable and being told to “Hold up” and “Get over,” as they slipped about very much on the uneven stones. Or you might, if you came out at another door (every room had at least two doors), go straight down to the hall again by half-a-dozen steps and a low archway, wondering how you got back there or had ever got out of it.

At least I think that’s an analogy!!

(Somehow, I mean something that I can’t very well express, but you’ll make it out.) —Richard Carstone, Chapter 23

A clever man that Mr Charles Dickens!

LikeLiked by 1 person

The scene of Krook’s death, with his body turning to smoke and ash as it rises into the night sky, is so eerie in retrospect because it seems to foreshadow the horrors of the century that would follow.

LikeLiked by 4 people

I’ve been rereading the Krook combustion passage aloud to Boze with the greatest enthoosymoosy. (Isn’t it one of the most juicy, gross, deliciously disturbing passages in all literature, with the greasy atmosphere, the stench, the oil that pervades the scene?) I think it is fascinating how, as we enter into the scene with Guppy and Weevle, the narrative switches to a present tense, making us, quite notably, active participants in the scene.

“…What is it? Hold up the light.

Here is a small burnt patch of flooring; here is the tinder from a little bundle of burnt paper, but not so light as usual, seeming to be steeped in something; and here is—is it the cinder of a small charred and broken log of wood sprinkled with white ashes, or is it coal? Oh, horror, he IS here! And this from which we run away, striking out the light and overturning one another into the street, is all that represents him.

Help, help, help! Come into this house for heaven’s sake! Plenty will come in, but none can help. The Lord Chancellor of that court, true to his title in his last act, has died the death of all lord chancellors in all courts and of all authorities in all places under all names soever, where false pretences are made, and where injustice is done. Call the death by any name your Highness will, attribute it to whom you will, or say it might have been prevented how you will, it is the same death eternally—inborn, inbred, engendered in the corrupted humours of the vicious body itself, and that only—spontaneous combustion, and none other of all the deaths that can be died.”

Dickens has employed this technique before…I am remembering one of his Sketches where we, the reader, are participating with him as an observer of a case going forward in court, I believe. It is effective and rather startling–as though he is saying…if you’ve been sleeping up until now, wake up! This–the Chancery–is doomed to explosion, corruption, death from within!

LikeLiked by 1 person