WHEREIN WE REVISIT OUR fifth and sixth week’s READING OF Bleak House (WEEKs 80-81 OF THE DICKENS CHRONOLOGICAL READING CLUB 2022-24); WITH A CHAPTER SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION WRAP-UP; CONTAINING A LOOK-AHEAD TO WEEKs seven and eight.

(Banner Image: “A Bird of Ill-Omen,” by Fred Barnard.)

By the members of the Dickens Club, edited/compiled by Rach

“Dead, your Majesty. Dead, my lords and gentlemen. Dead, Right Reverends and Wrong Reverends of every order. Dead, men and women, born with Heavenly compassion in your hearts. And dying thus around us, every day.”

Friends, we’ve had some heavy-hitting chapters over the past two weeks, between the reunion of Esther with her mother, followed by the death of the victim of society’s collective irresponsibility: the poor crossing-sweeper whose inadvertent connections with “greater” happenings have brought him into contact with those who would otherwise prefer to ignore his existence.

The insights were so marvelous and complex that sometimes I was simply unable (unwilling?) to edit them down; but, on the other hand, I had so many comments to incorporate that I might have inadvertently missed something. Apologies in advance!

Before we get into our summary and discussion wrap-up this week, a few quick links:

- General Mems

- Bleak House, Chs 33-49 (Weeks 5 & 6): A Summary

- Discussion Wrap-Up (Weeks 5 & 6)

- A Look-Ahead to Weeks 7 and 8 of Bleak House (25 July to 7 Aug, 2023)

General Mems

SAVE THE DATE: Join us for our online discussion of Bleak House! Saturday, 12 August, 11am Pacific (US)/2pm Eastern (US)/7pm GMT (London)! Please feel free to message Rach here on the site, or on twitter, to get on the list for the Zoom link that she’ll send out in early-August.

If you’re counting, today is Day 567 (and week 82) in our #DickensClub! This week and next we’ll be on Weeks 7 and 8 of Bleak House, our eighteenth read of the group. Please feel free to comment below this post for the seventh and eighth week’s chapters, or use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter.

No matter where you’re at in the reading process, a huge “thank you” for reading along with us. Heartfelt thanks to our dear Dickens Fellowship, The Dickens Society, and the Charles Dickens Letters Project for retweets, and to all those liking, sharing, and encouraging our Club, including Gina Dalfonzo, Dr. Christian Lehmann and Dr. Pete Orford. Huge “thank you” also to The Circumlocution Office (on twitter also!) for providing such a marvelous online resource for us.

And for any more recent members or for those who might be interested in joining: the revised two-and-a-half year reading schedule can be found here. For Boze’s marvelous introduction to Bleak House and for our reading schedule, please click here. For Chris’s supplementary intro reading material, please click here. If you’ve been reading along with us but aren’t yet on the Member List, we would love to add you! Please feel free to message Rach here on the site, or on twitter.

Bleak House, Chs 33-49 (Weeks 5 & 6): A Summary

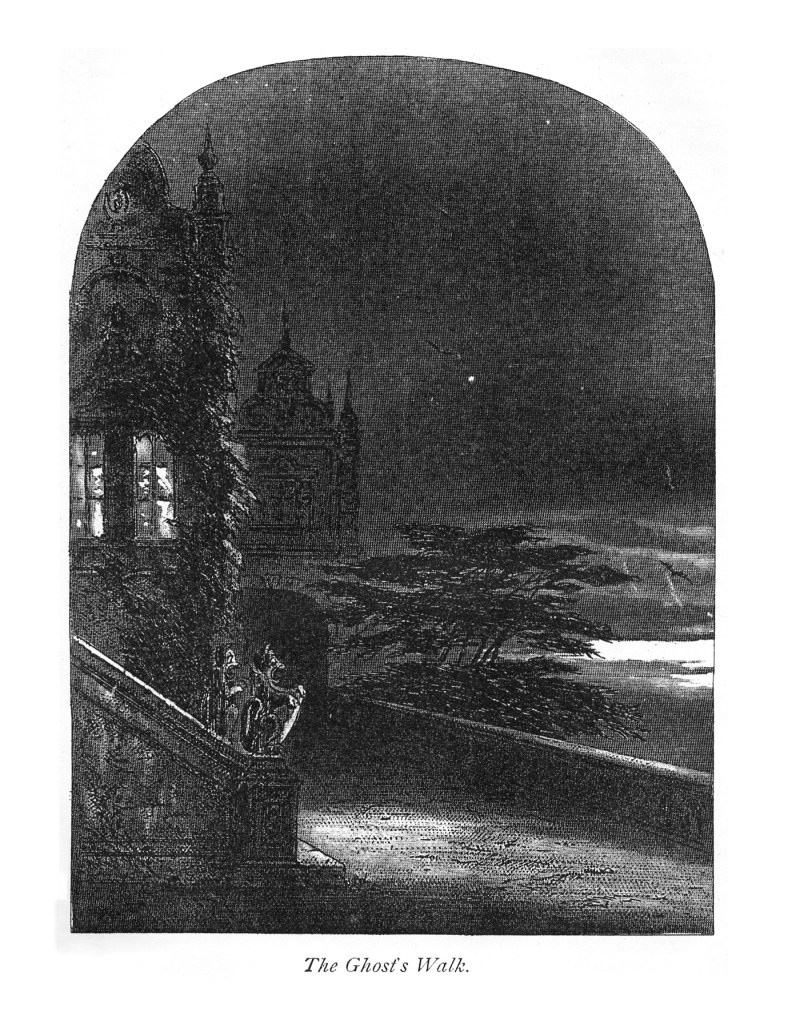

(Note: The below illustrations are by “Phiz,” Hablot Knight Browne, from the original edition, and have been downloaded from the marvelous Charles Dickens Illustrated Gallery. Thank you!)

A busy tavern, the Sol’s Arms, is hopping with business because of the inquest after Krook’s death. Mrs Snagsby continues in her suspicions of her husband’s doings, and Weevle/Jobling no longer wishes to reside at the rag and bottle shop in spite of Mr Guppy’s pleadings and negotiating. Meanwhile, Smallweed barges in with the news that the whole of Krook’s property now belongs to him, as his wife was Krook’s sister and next of kin.

“We shall make good our title. It is in the hands of my solicitor. Mr Tulkinghorn of Lincoln’s Inn Fields…Shake me up, somebody, if you’ll be so good…”

Mr Guppy pays a visit to Lady Dedlock, informing her of the strange turn of events at Krook’s. She asks whether the letters were destroyed in the same fire that destroyed Krook, and he believes so. But before Guppy can take his leave, he runs into Mr Tulkinghorn, who finds Guppy alone with Lady Dedlock and is immediately suspicious.

Poor Mr George is again harassed about the repayment of a loan from Smallweed, who threatens to come after the Bagnets, who had cosigned it. Mrs Bagnet, with her husband, comes in lamenting it all, but ultimately feels sure that George will take care of it. When Mr Bagnet and Mr George get nowhere by talking to Smallweed, they visit Tulkinghorn as requested. George proposed that the Bagnets be freed from the obligation if he, George, shows the writing of Captain Hawdon, as Tulkinghorn had long wished. Tulkinghorn agrees.

Esther is recovering. Her eyesight, which had been temporarily affected, is restored, but her face is marked by the smallpox, and she can’t yet bear to see Ada; only her guardian. Esther takes Boythorn up on his offer to stay at his place, which she will have to herself for a time, to assist in her recovery. Charley informs Esther, during a visit from Miss Flite who had walked many miles to inquire about Esther, that a lady took the handkerchief that Esther had kindly left with Jenny, leaving Jenny some money for it. Miss Flite tells Esther of the heroic Dr Woodcourt, who, having been shipwrecked, was now a hero for his valiant efforts to save and attend to the wounded and dying. Esther is grateful, for Woodcourt’s sake, that he had never made any overt declaration of love, now that her appearance is altered, so that he would feel no obligation to continue courtship. Miss Flite also warns Esther that Richard be held back before he ends up like others she has known, including Gridley.

“’I know what will happen. I know, far better than they do, when the attraction has begun. I know the signs, my dear. I saw them begin in Gridley. And I saw them end. Fitz-Jarndyce, my love,’ speaking low again, ‘I saw them beginning in our friend the Ward in Jarndyce. Let some one hold him back. Or he’ll be drawn to ruin.’”

While walking on the grounds during her stay at Boythorn’s home in Lincolnshire, while anticipating a visit from Ada, Esther is approached by Lady Dedlock, who dismisses Charley in order to tell Esther the secret that must not be alluded to any longer: that she, Lady Dedlock, is her mother.

“O my child, my child, I am your wicked and unhappy mother! O try to forgive me!”

Falling on her knees in agony, Lady Dedlock says also that she and Esther must have only this moment of reunion; that Esther must hereafter consider her as one dead, and her secret held close (except to Mr Jarndyce—whom Lady Dedlock says Esther may tell), so that it may not become known to others. Esther learns of Sir Leicester’s lawyer, Tulkinghorn, of whom Lady Dedlock is afraid.

“’My child, my child!’ she said. ‘For the last time! These kisses for the last time! These arms upon my neck for the last time! We shall meet no more. To hope to do what I seek to do, I must be what I have been so long. Such is my reward and doom. If you hear of Lady Dedlock, brilliant, prosperous, and flattered; think of your wretched mother, conscience-stricken, underneath that mask! Think that the reality is in her suffering, in her useless remorse, in her murdering within her breast the only love and truth of which it is capable! And then forgive her, if you can…’”

That evening, Esther finds herself, during her walk, in the courtyard which is the setting of the Ghost Walk’s tale…

“…there was a dreadful truth in the legend of the Ghost’s Walk; that it was I, who was to bring calamity upon the stately house; and that my warning feet were haunting it even then. Seized with an augmented terror of myself which turned me cold, I ran from myself and everything, retraced the way by which I had come, and never paused until I had gained the lodge-gate, and the park lay sullen and black behind me.”

Finally, the time for Ada’s arrival comes, and Esther’s fears that there would be some change in Ada’s manner towards her was completely put to rest: “The old dear look, all love, all fondness, all affection.” Esther and Ada spend time with Richard, who is clung to tenaciously by Skimpole. Rick has now hired a Mr Vholes to assist him in the Chancery case, being wholly dissatisfied with Kenge & Carboy and the whole business. Esther and Ada try by persuasion and by letter to convince him to drop the case, but to no avail.

After Esther’s return to Bleak House, she visits Caddy in London, delighting in her ambitions to learn piano and fiddle to try and help Prince in his lessons. (The fathers of Caddy and Prince have become friends, and Peepy is staying with Caddy and Prince.) But the visit to London was, for Esther, primarily to have a chat with Mr Guppy, and to beg him to drop his searches into Esther’s birth and connections. Guppy hears this in relief—as the sight of Esther’s altered visage due to the smallpox has made him regret his earlier declaration to her, and he won’t rest until a third party has been witness to her reiterating her earlier rejection of him.

Guppy, meanwhile, goes with Jobling—under the pretext of seeing whether the latter has left anything in Krook’s lodgings before leaving—to find out whether or not Hawdon’s letters had survived the combustion. There they encounter Tulkinghorn, who makes a wry comment about Guppy’s business with Lady Dedlock, of which Guppy says nothing.

At Chesney Wold, Sir Leicester and Lady Dedlock hear reports of the ironmaster, Mr Rouncewell’s, success in local elections, and the conversation turns to Rosa, with whom Lady Dedlock is still reluctant to part. Tulkinghorn tells an apocryphal story of a girl in similar circumstances to Rosa’s, who had been touched by the taint of scandal, and removed from the patronage of a great lady who had taken a fancy to her. Lady Dedlock maintains her haughty, dispassionate demeanor throughout. But now she knows that Tulkinghorn knows of her past; she confronts him about this after and says she intends to leave Chesney Wold in order to protect Sir Leicester in case all becomes known, Tulkinghorn will not allow this, as it will be a suspicious act and distress Sir Leicester. She is to continue in her present life, which Tulkinghorn now has an unusual degree of knowledge of, and control over.

Back in London, Tulkinghorn confronts Hortense, who has been harassing the Snagsbys, making Guster fearful of her job and Mrs Snagsby suspicious of Mr Snagsby. Hortense angrily condemns Lady Dedlock and demands employment to help destroy her former mistress. Tulkinghorn threatens her that he’ll report her for her behavior if she harasses the Snagsbys again.

Richard continues in his increasing distrust of Mr Jarndyce, thinking him his enemy in Chancery, and Ada, though distressed by this, still loves Richard too much to blame him. Mr Jarndyce, Ada and Esther try and convince Skimpole to refuse Rick’s generosity. Meanwhile, Sir Leicester apologizes personally to Jarndyce for any misunderstandings regarding the prohibitions of Sir Leicester’s grounds and hospitality—this is only for Mr Boythorn, and not relevant to Jarndyce and his wards. Esther finally reveals the truth to Mr Jarndyce later, about Lady Dedlock. Esther in turn finds out from Jarndyce that it was Lady Dedlock’s sister—Esther’s godmother—who had been engaged to Mr Boythorn but couldn’t keep it, due to some falling out between the sisters, and needing to care for Esther.

Jarndyce has long been troubled about something he has wanted to ask Esther; she begins to have an inkling at last of what it is, and gives him permission to ask it—which he does some time later, in a letter: to have her hand in marriage. Esther burns the flowers from Woodcourt that she had dried and kept. After some time—when, to her surprise, Jarndyce does not bring it up again—she goes to him and says that, yes, she will be the mistress of Bleak House.

Hearing from Vholes that Richard is deeply in debt and getting ready to resign his army commission to devote all energy to the Chancery case, Esther visits Richard in Deal with a letter from Ada—who is ready to give him her fortune so that he can pay his debts and keep his current position. Richard blames Jarndyce for all this. Esther also sees Mr Woodcourt in the crowd, for the first time since he had left. Initially running away so that he won’t see her altered appearance, she berates herself and meets with him and Richard. Woodcourt assures Esther that he will keep an eye on Richard, who could use a friend.

Woodcourt encounters both Jenny and Jo near Tom-all-Alone’s. Cornering Jo after giving chase for what he believed was theft, Woodcourt then realizes that Jo is ill, and gains Jo’s trust and hears his full story, and how Esther had helped him and then became sick herself, and how he was forced to leave after being taken in by Mr Jarndyce. He whispers the name of the one who had forced him out.

Woodcourt tries to feed Jo, but Jo is too ill. On the advice of Miss Flite, they go to Mr George’s gallery, and George takes Jo in. Jarndyce and the Snagsbys are informed of Jo’s situation, and pay visits. Jo is made as comfortable as possible, but his condition continues to decline. As Woodcourt teaches Jo the Lord’s Prayer while Jo hopes that a light might soon be coming, the boy dies…he “moves on” at last.

“Dead, your Majesty. Dead, my lords and gentlemen. Dead, Right Reverends and Wrong Reverends of every order. Dead, men and women, born with Heavenly compassion in your hearts. And dying thus around us, every day.”

Meanwhile, Lady Dedlock finally must let her beloved Rosa go; she summons Mr Rouncewell that he might now take custody of her, with Sir Leicester’s permission. Tulkinghorn is angered that Lady Dedlock acted of her own accord and without consulting him, and tightens the reins around her, informing her that the disclosure of her past to Sir Leicester will be made by him soon. Lady Dedlock, complaining of a headache, later takes a walk.

The next morning, the morning after a gunshot had been heard the previous night near Tulkinghorn’s office, we discover that Mr Tulkinghorn has been shot through the heart.

Lady Dedlock was not the only one seen walking in the area the previous night; Mr George was, too. Bucket pays George a visit at the Bagnet’s residence—where they are celebrating Mrs Bagnet’s birthday—and after George and Bucket leave, Bucket arrests George for the murder of Mr Tulkinghorn.

Discussion Wrap-Up (Weeks 5 & 6)

Firstly, three cheers for Mrs Bagnet!

Dickens’s “Writing Lab”: Characterization and “Coincidence”; Miss Barbary; the “Connective Tissues” of the Story; Mr Guppy

The Stationmaster brings up an interesting point: there is more mystery and complexity surrounding Esther’s godmother–Miss Barbary–than we initially think. However unthinkable her action and attitude, was it motivated by some semblance of nobility–at least in her own mind?

I responded:

And here Chris analyzes that mysterious character, Miss Barbary:

Directly relating to Dickens’s “Writing Lab,” Chris discusses the almost unimaginable ways in which characters are connected with one another–a true juggling act:

Lenny loves the analysis here, and adds, bringing in Guppy as a prime example of the “connector” characters:

Chris responds with some wonderful insights and quotes:

I had to add in a word in praise of Guppy, a true “detective”:

Lenny also considers Esther, though a fully three-dimensional character, almost as another “connector” or “device”:

Esther and the Narration

And speaking of our heroine, the Stationmaster starts us off on some insights into aspects of Esther’s characterization that were either good, or just distracting:

And the “sick burn” Esther got in: is this a sign of her barbed wit and insight, or a flaw in Dickens’s narration?

The Stationmaster also brings up an interesting question about Esther:

“There’s something potentially disturbing about the scene which Linda M, Lewis points out though. While Esther says she’ll never desert her mother, she doesn’t encourage her to seek God’s forgiveness. The closest she comes is suggesting she lie her cards on the table with Tulkinghorn or Mr. Jarndyce. Contrast this with Rose Maylie’s interactions with Nancy in Oliver Twist. (‘It is never too late for penitence and atonement.’) Could it be that because of her upbringing Esther doesn’t believe there is forgiveness in Heaven for her mother? That’s depressing.”

~Adaptation Stationmaster

I respond that there might be several reasons for this:

“What’s in a Name”: Dedlock

“’Slow torturing’ just about sums Tulkinghorn’s character and activities to the ‘T.’ But I think it also stands for the ways in which the Jarndyce suit in Chancery affects so many characters in the novel, especially our dear Richard. He is literally being tortured to death–as is Lady Dedlock.”

~Lenny H.

Lenny, after this comment, was really pondering that evocative name, “Dedlock”. Chris responds:

Shakespeare and Dickens

Friends, I’m keeping this topic going as often as I can, especially because Rob is falling down the Shakespeare-Dickens rabbit hole, and I for one can’t wait to read more about it!

And the Stationmaster writes:

But if you really want some Shakespeare & Dickens this week, check out Rob’s marvelous analysis of Tulkinghorn–here (Othello) and here (Macbeth)–which I put under our Tulkinghorn discussion.

Telescopic Philanthropy and Colonialism

The Stationmaster writes:

Lenny considers whether this passage–and some of the characters we encounger, e.g. Mrs Jellyby–are not only commentaries on “telescopic philanthropy,” but of colonialism:

On Richard, Obsession, Self-Destruction–and Spontaneous Combustion?

Of the three characters that we have, perhaps, focused most on this week–Miss Barbary, Tulkinghorn, and Richard–Richard is certainly the most sympathetic, and Dickens does this so well:

Lenny replies, and also considers others in this novel whose obsession drives them to something akin to madness:

Lenny also brings us back to Mr Pickwick, who, though through a more comical incident (the misinterpretation of the conversation with Mrs Bardell), is obstinate enough to be drawn into the Fleet prison. Might Richard have benefitted from a Sam Weller? Esther tries pleads with Mr Woodcourt to be that friend he lacks, but perhaps by that time, it is too late…

Rob takes us on a wonderful journey of quotes that illustrate Richard’s trajectory:

Sadism, Secrets, and Control-Hungry Underlings: Tulkinghorn

How did Tulkinghorn come to be as he is? The Stationmaster considers:

Rob responds with the most marvelous allusions to some of Dickens’s possible literary influences:

Chris considers that Tulkinghorn is “toying with” Lady Dedlock:

I add:

And Rob continues his marvelous analysis of literary influences on Tulkinghorn, with the many Othello/Iago connections:

“Personal and Collective Responsibility” and Its Displacement; “Spiritual and Psychological Slavery”

Daniel posted his beautiful reflection on the “displacement” of responsibility, and the post can be found here. This is such a key theme to keep at the forefront that I selected a representative paragraph from his post:

A Look-Ahead to Weeks 7 and 8 of Bleak House (25 July to 7 Aug, 2023)

This week and next we’ll be finishing Bleak House, Chapters 50-67, which constitute the monthly installments XVI-XX (the final month was a double number) published between June and September 1853. Feel free to comment below for your thoughts, or use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter.

Another wonderful summary and masterful drawing together of the thoroughly interesting discussion points. I am in awe of how you do what you do, Rach! But thank you so much for doing it 😀

I wish I had included the following passage at the beginning of my list of quotes punctuating Richard’s deterioration, but perhaps mentioning it now it may be borne in mind as we accompany Richard and Ada towards our journey’s end.

The door stood open, and we both followed them with our eyes as they passed down the adjoining room, on which the sun was shining, and out at its farther end. Richard with his head bent, and her hand drawn through his arm, was talking to her very earnestly; and she looked up in his face, listening, and seemed to see nothing else. So young, so beautiful, so full of hope and promise, they went on lightly through the sunlight as their own happy thoughts might then be traversing the years to come and making them all years of brightness. So they passed away into the shadow and were gone. It was only a burst of light that had been so radiant. The room darkened as they went out, and the sun was clouded over.

— Esther (C13)

LikeLiked by 2 people

Dear Dickens Reading Club Members, especially Rob to whom this comment responds (to his 23 Jul 2023 at 2:56 pm reply in Weeks 3-4 section):

Allude away! No apologies necessary! I am woefully ignorant about Shakespeare – I’ve only read a very little and not with anyone at all well-versed. I so appreciate our members’ scholarship overall but especially related to poets – Shakespeare, Byron, Carlyle, Tennyson, et al – with whom I am sadly (and a bit embarrassingly) unfamiliar. This is one of the MANY beauties of this wonderful group!

Continuing education forever!

Thank you all.

P.S. – Rach, Thanks for another fabulous round-up!

LikeLiked by 4 people

I know just enough about Shakespeare to be dangerous. LOL.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Egads, Rach, what a lot of fine work you’ve put into this summary of the recent chapters and of the following two week’s momentous dialogues we’ve had about BLEAK HOUSE You’re just such an expert at this, that I’m just blown away by the results of both that you have come up with, here. I just love reading both segments, as they jog my memory about events and characters, while reviewing the helpful and insightful analyses our group has come up with in the past two weeks. In fact, you catch completely what I think is the rising crescendo of this last period as, in the final couple of days, there is just such a rush of wonderful and pertinent ideas that have surfaced in the brilliant remarks or our members. Jeez, I just want to bottle all of this for posterity. Your cogent and beautifully written summaries have just opened up the meanings of this novel in so many ways that I’ve not anticipated! Thanks so much, again, for your glorious endeavor, here!

LikeLiked by 2 people

oh, my, “of” for “or”! Sorry ’bout that!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gosh, Lenny 😭 and Rob and Chris, thank you so, so much for these kind words…I had to rush out of the room to read them aloud to Boze…it really means the world! (Getting a bit teary!) What a phenomenal group we have, and how it opens up so much depth and richness in the text…which is a gold mine! Three cheers for Dickens, & our Club! 🥳🎩🖤

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’d just like to say I really like one of the quotes that Rob listed (I mean, I like them all but especially this one) about how Richard is strangely angry at Jarndyce for thinking he’s not a steady character or a good provider for Ada when he’s confided in her that he actually thinks that about himself. It feels very psychologically astute to me. We often hate the people who accuse us of the things we fear about ourselves. Of course, I wouldn’t want to assume that whenever someone gets mad about an accusation it’s because deep down, they suspect it’s true. In many cases, they’re offended because they believe it’s really not true. But I suspect there may be a lot of cases like Richard’s too.

LikeLiked by 2 people

“Egads, Rach,” indeed!

I merely echo and fan into flame all of the appreciative comments about Rachel’s masterful weaving of a tapestry from the various, colorful threads of commentary and conversation!

As I have observed before, participation in this chronological reading club group is akin to a graduate seminar on Dickens! No exaggeration, just fact.

One quick additional addendum to the “connections, connections, connections” observation.

“’To be’ is to inter-be. You cannot just be by yourself alone. You have to inter-be with every other thing.”

–Thich Nhat Hanh

Dickens dazzles us with his capacity to see and articulate the myriad interconnections among the characters and their interweaving lives.

The Inimitable is the Grand Fashioner of warp and woof!

LikeLiked by 4 people

I forgot to mention before that I was struck this week by the parallel between Allan Woodcourt’s relationship with Miss Flite and Betsey Trotwood’s relationship with Mr. Dick. (“Now, you have a fund of knowledge and good sense and can advise me.”)

This last section of the book is full of suspense and if you haven’t read it before, I beg you not to read my comments until you have because I’m going all out with the spoilers!

This is similar to what I’ve mentioned in a previous comment, but I love how Dickens conveys Esther’s squeamishness about marrying Jarndyce without her explicitly writing about, just by how she glosses over explaining her situation to Caddy and Ada and by how she only refers to marrying Jarndyce as becoming the mistress of Bleak House.

Chapter 51 gives us the only example I can think of Esther the narrator depicting a conversation/scene that was relayed to her by someone else. This confirms me in my impression that she’s not the third person narrator but if you do think she is, well, the scene doesn’t disprove it or anything.

I love the subtle pun in Chapter 52. “Bucket is so deep.”

What stands out to me about Bleak House’s climactic murder mystery is how many red herrings Dickens includes. Not as many as some authors would have done but more than I expect from him. It’s not a huge shock when the culprit’s identity is revealed since she’s the only suspect with whom we don’t sympathize and otherwise Chapter 42 would be pointless. But Dickens gives us enough misdirection about Mr. George and Lady Dedlock to keep the question open in our minds or at least to think Mr. Bucket thinks it’s one of them.

I love the double meaning of Chapter 54’s title, Springing a Mine. Inspector Bucket has sprung a mine on Hortense but sadly he has also had to spring one on Sir Leicester.

It’s amusing how such a dramatic chapter finds time for Mrs. Snagsby to rant about her husband and his supposed affair.

Mrs. Bucket is an intriguing offstage character. Even more than Mrs. Bagnet, she doesn’t seem to fit in much with Bleak House’s messages about femininity. Generally, the book positively portrays domestic minded women like Esther, Caddy (eventually) and Ada positively while portraying women who seek to a more “masculine” life, such as Mrs. Pardiggle or Miss Wisk, negatively. (Esther does end up playing an important role in the rugged search for Lady Dedlock but this comes across as her acting against her nature out of necessity. I’m saying that to praise the character’s devotion and heroism BTW, not to criticize it.) Mrs. Bucket seems totally at home doing detective/spy work with her husband, completely pulling the wool over Hortense’s eyes. Of course, she’s doing it to help out Inspector Bucket, but Chapter 53 explicitly describes her as “a lady of a natural detective genius, which if it had been improved by professional exercise, might have done great things, but which has paused at the level of a clever amateur.” Part of me would have liked to have seen more of Mrs. Bucket or really to have seen her at all since we technically only hear of her. But the rest of me thinks that there are too many major characters in this book as it is and Mrs. Bucket’s role in the story is more fun as a surprise.

Here’s another small detail that stood out to me on this read, one I’d never thought about before. When describing Mrs. Rouncewell’s intense emotions on her reunion with George, Dickens casually mentions “a better son loved less.” How does he intend us to react to that? In the middle of this generally heartwarming scene in which we sympathize with Mrs. Rouncewell so much, are we supposed to dislike her a bit and pity her other son?

It’s humorous how Mrs. Bagnet refrains from speaking to George throughout the scene of his reunion with his mother and just prods him with her umbrella, but it also illustrates something cool about her character. She has a forceful personality, but she also knows when to be quiet.

For all that Guppy’s a jerk and lost all interest in Esther after her face was marred, it’s kind of nice that, for her memory, he gives her mother the heads up about her exposure. Or is he just doing that because he’s still scared if he doesn’t, Esther will lay claim to his hand?

LikeLiked by 3 people

It’s a pity Dickens didn’t tell us Nemo was a captain until after we learned his real name. In doing so, he deprived us of a bevy of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea jokes.

Sir Leicester Dedlock is one of the most fascinating characters in Dickens to me, but I haven’t been able to talk about why until this part of the book. On the one hand, Dickens takes a negative, satirical view of his politics. He even indicts him in the corruption of Chancery in Chapter 2. (“Sir Leicester has no objection to an interminable Chancery suit. It is a slow, expensive, British, constitutional kind of thing.”) We might say that when Sir Leicester is devastated by the revelations about his wife, he becomes on the outside what he always was on the inside. (“His voice was rich and mellow, and he had so long been thoroughly persuaded of the weight and import to mankind of any word he said that his words really had come to sound as if there were something in them. But now he can only whisper, and what he whispers sounds like what it is—mere jumble and jargon.”) On the other hand, he becomes not only a tragic character in the last section of Bleak House but a heroic admirable one. The detail of him keeping the fires in his house going for Lady Dedlock recalls Daniel Peggotty and Emily. The fact that the joyous final chapter about the Rouncewell family portrays their fortunes rising and the melancholy final chapter about the Dedlock family shows their fortunes falling has been interpreted, reasonably enough, as an endorsement of the former and an indictment of the latter. But it also has the effect of making the Dedlocks underdogs. Then there is the contrast in Chapter 63 between the “fresh green woods as those of Chesney Wold” and the “coal pits and ashes, high chimneys and red bricks, blighted verdure, scorching fires, and a heavy never-lightening cloud of smoke” of the Iron country which anticipates Coketown in Hard Times.

I love the description in Chapter 63 of how everyone is talking about Lady Dedlock’s disgrace even the people who didn’t really care about her one way or the other before. It reminds me of how everyone talks and jokes about whatever celebrity has made a fool of themself in the public eye lately. I don’t care much about celebrities myself and I imagine they usually bring the humiliation on themselves, but whenever people do that, it strikes me as vulture-like even when the gossipers are just joking and not making any self-righteous judgements. Indeed, I prefer the ones who make judgements. They may be vulture-like but at least they care about morality.

Inspector Bucket is the one of the most truly neutral characters in Dickens. On the one hand, he spends the first half of the book assisting Tulkinghorn, arrests George and is arguably responsible for the death of Jo. (He did put Jo in a hospital but there’s a reason Mr. Jarndyce didn’t just do that.) The description of him in Chapter 53 makes him sound like Tulkinghorn’s successor or reincarnation. “He makes for Sir Leicester Dedlock’s, which is at present a sort of home to him, where he comes and goes as he likes at all hours, where he is always welcome and made much of, where he knows the whole establishment, and walks in an atmosphere of mysterious greatness.” On the other hand, he brings Hortense to justice, leads the search for Lady Dedlock, gives Mrs. Snagsby some much needed marriage counseling and resolves Jarndyce and Jarndyce, humiliating Smallweed in the process. You might say he embodies the law in how he helps both the heroes and the villains, depending on the circumstances.

I’ve criticized the way Esther repeatedly apologizes for writing so much about herself in the past, but I really do like the beginning of Chapter 60, how she begins by writing that she’s going to pass over her time of grief, says that she only mentions it at all because of the goodness shown by her friends then and then starts a new paragraph by repeating her first sentence, “I proceed to other passages of my narrative,” before actually proceeding. It really conveys that she’s referring to a time she doesn’t like to recall but she can’t help being distracted by memories while she’s writing this. At some points in these final chapters, Esther sounds a bit like David Copperfield, the way she says she can still see things before her. I’m sorry I can’t think of any specific examples.

I love the description of how Esther feels “half defeated” before she even begins to try reasoning with Skimpole. Some people are like that. They’re just so easygoing on the surface that, intentionally or not, they make you feel guilty for criticizing them even when they really deserve it.

Speaking of Skimpole, I’ve heard he was modeled on the writer Leigh Hunt. Does anyone know where I could read any of Hunt’s writing so I could see how Skimpole is a parody of him? Several characters from Bleak House are actually supposed to have been modeled on public figures Dickens. Mrs. Jellyby was Caroline Chisholm. Laurence Boythorn was Walter Savage Landor. Inspector was Charles Field. Dickens’s sister-in-law, Georgina Hogarth, thought Esther Summerson was based on herself.

Both the 1985 and the 2005 miniseries of Bleak House interpret Guppy regaining interest in Esther to mean that her smallpox scars have faded, and her good looks have been restored. This is reasonable enough as the book’s final chapter implies that Esther regains her beauty at some point but it’s not clear when this happens. It’s just as possible to interpret Guppy as having decided that he really does love Esther no matter how she looks. A third possibility is that now that her parentage is something of an open secret, Guppy just wants to use it somehow to leach off of Sir Leicester. For such a seemingly shallow comedic character, Guppy’s motives sure can be hard to interpret sometimes. Maybe he has a future as a lawyer after all.

While Richard has finally lost all hope in Chancery in his last moments, he still clings desperately to some kind of hope but now it’s only the hope that he will live.

I thought Miss Flite was going to release her birds when her own suit was resolved, not Jarndyce and Jarndyce? Did I get that wrong? Or is her releasing her birds supposed to convey that she’s finally given up hope for herself?

While I don’t believe for a moment that Esther was really in love with John Jarndyce, I almost wished they had ended up together since so much more of the book was devoted to developing their relationship and conveying the bond between them than it was to that between her and Allan Woodcourt. I don’t really care about him at the end and even Esther technically devotes more space in the last chapter to praising Jarndyce.

In our David Copperfield discussion, some people, I among them, criticized the happy ending for being a little too convenient. Little points of discontent in Bleak House’s ending, mainly Prince Turveydrop being lame and his child deaf and dumb, keep it from having that problem IMO.

What do people imagine to be the implied ending of the book’s abruptly cut off final sentence, “they can do very well without much beauty in me-even supposing-?” Is it “even supposing I am really beautiful?” “Even supposing I am really ugly?” “Even supposing they lose their beauty?” What do you guys think?

LikeLiked by 3 people

Some of Leigh Hunt’s works are on https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/author/3612

LikeLiked by 2 people

Love your character analyses, Stationmaster! I agree that Sir Leicester is such a fascinating character. As to Bucket, I see what you mean…though I don’t see him so much “neutral” or as being responsible in some way for Jo’s death as…well, like you say, representing the law and hence, having to serve both good and bad. I think it’s more like, Inspector that he is, he is too caught up in the details for a while, that it takes him a bit to see the bigger picture, the implications of everyone’s actions. He serves Tulkinghorn for a while; there must be some reason to feel justified in doing so–until more is revealed, & Tulkinghorn murdered. If Bucket has a weakness, it’s probably a bit of the-ends-justify-the-means mentality…I’ll go ahead and do *this*, so that *this* will happen or be revealed, not considering personal feelings or repercussive implications. But all that being said, I do adore Bucket. I love the sketch about being “on duty” with Inspector Field, & how Field is portrayed as a bit godlike, with all the deference shown him, and his sense of who to ask for information, where to look. I LOVE the bits about Mrs Bucket, and I agree that she would have been a marvelous addition to the big cast, as more than just an offstage character.

Yes, as to Skimpole/Leigh Hunt. Hunt was a connector between many, many influential literary figures. Lots of meetings between the “greats” seemed to take place at his home; he knew the great poets of the Regency/Romantic period (Keats, Shelley, Byron) & was lionized for getting put in prison for a couple of years on libel charges, because of things he said about the Prince Regent. But his “prison” was extremely cushy & comfy, and more like a personal salon, where he received many famous guests, and was financially supported by lots of folks. I don’t know exactly what characteristics, besides financial support from others and perhaps a certain irresponsibility(?) were inspired by Hunt for Skimpole, but apparently the likeness was so strong that it was widely noticed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As I experienced at the end of “Dombey and Son”, I am left at the end of “Bleak House” wondering about backstories, continuing stories and the welfare of the wonderful characters we’ve spent the last couple of months with.

Mostly I want to know the backstory, the tragic love story, of Honoria and Captain Hawdon. Were they really engaged as Tulkinghorn suggests in Ch 40 and if so, what prevented them from marrying even if they, like Richard and Ada, simply “went out one morning and were married” (Ch 51)? Honoria clearly carries a torch for Captain Hawdon, and it seems Captain Hawdon did likewise for her. So what happened?

Perhaps Hawdon’s and George’s army unit shipped out before the marriage could be arranged. If it is as simple as this it seems some arrangement could have been made for Honoria to join Hawdon at his posting and marry him there. But this didn’t happen. They never saw each other again. So what happened?

I think something momentous, something cruel happened to separate them. Something that resulted in causing Hawdon to spiral downward to the point of suicide. Mr George’s account of Hawdon’s state of mind in Ch 21 suggests he (George) knew Hawdon both during and immediately after Hawdon’s relationship with Honoria (whom he also knew as evidence by his recognition of Esther’s similarity to her in Ch 24). Whether George was a confidant or simply a go between remains unclear. Also unclear are particulars about Hawdon’s apparently drowning – when in the timeline did it happen, why was George not onboard the transport-ship, and just why did Hawdon do it? (Ch 21, 63) Did he do so because he was trying to get back to his lovely Honoria and their child? Did he even know she was pregnant or that she had the child? And at what point, if ever, did he learn she was married to Sir Leicester? Was it the knowledge of any or all of this that led to his melting into the offal of London and to his final dissipation?

I think the something momentous and cruel that happened is Miss Barbary and the answers to some of these questions lie in when and how she enters the picture. First of all, where are these sisters’ parents? Perhaps they are dead and Miss Barbary, being the elder sister, felt responsible for her younger (wilder?) sister, Honoria. Had she been aware of her sister’s love affair throughout, offering sisterly advice and commiseration based on her own relationship with Mr Boythorn? Maybe she thought that she, as the elder sister, should be married first and felt jealous and betrayed by Honoria for overstepping her position. Or perhaps she thought the dashing Captain had taken advantage of her young sister, or that he was not good enough for her, or found some other demerits in his character and had taken steps to separate the lovers. Or perhaps she had known nothing of their attachment until the crisis of Honoria’s pregnancy became obvious and then the shocked and mortified Miss Barbary was compelled to step in and clean up the mess. I’ve written before about Miss Barbary being described as a “good, good woman” in relation to her behavior toward Esther and how that description suggests misplaced motivations (see my 7/15/23 post). Whatever Miss Barbary’s motivation was for her behavior relative to Honoria and Hawdon, if she in fact was the cause of their separation, here again she mistakes righteousness for right-mindedness, mistakes love for sin, mistakes social appearances for something important, and mistakes responsibility for Responsibility.

The final mystery to this backstory is how did Honoria – post confinement, post Capt. Hawdon, and now estranged from her sister – rehabilitate herself to become a suitable marriage candidate for Sir Leicester Dedlock, Baronet – another love story – and the prima donna of society?

****

One other big backstory mystery is who were Jo’s parents and why was he abandoned to the streets? (Perhaps this isn’t so difficult to figure out.) How long was he on his own, how did he survive, and how, but for the grace of God, did he avoid meeting up with a Fagin and thus remain the uncorrupted innocent we know?

Miss Flite’s backstory, given in Ch 35, is enticing and tragic. How is her family connected to Jarndyce and Jarndyce and what are the details of The Fall of the House of Flite? (Good title!) But more importantly, I wonder how Miss Flite will fare now that the suit is over. I suspect Mr Jarndyce, or perhaps Esther and Allan, will take her in or provide her with a pension, or otherwise take care of her. I hope she is happy.

I don’t wonder too much about Mr Skimpole’s backstory because he is such an unlikeable person. I see him as a reimagining of Mr Pecksniff in his being purposely and determinedly oblivious to his shortcomings to such an extent that it is obvious to everyone except, so he says, himself that he knows full well what he is doing. I do hope, however, that his wife and daughters are able to better their situation now that the encumbrance of Harold is out of the way.

I’m glad that Mr George is reconciled with his family. His reunion with his brother the Ironmaster is especially heartwarming. This elder brother becomes more likable and less hard than he had been in the earlier scenes with Sir Leicester and Lady Dedlock. The description of “the iron country” to which Mr George travels to see his brother is a nice prelude to “Hard Times” – “coal pits and ashes, high chimneys and red bricks, blighted verdure, scorching fires, and a heavy never-lightening cloud of smoke become the features of the scenery”. (Ch 63) The Brothers Rouncewell are an interesting contrast to the Sisters Barbary. Mr Rouncewell, the elder, is more than willing to forgive and forget his brother’s waywardness and welcome him and reestablish his place in the family. He also knows full well that his younger brother is their mother’s favorite but doesn’t hold it against him, rather, he uses this fact to encourage George to accept their mother’s legacy and maintain peace in the family. (Ch 63)

I like to think of Mr Guppy as a Tulkinghorn in training – now that Tulkinghorn is dead there is an opening for “a great reservoir of confidences” to the rich and famous. I wish Mr Guppy well if this is his ambition and hope he can manage it without too much loss of his winning personality and does not become the “hard-grained man, close, dry, and silent” that was Tulkinghorn. (Ch 22). I shudder to think that Mr Vholes will aspire to this position, though he already has the demeanor for it. He is too full of himself to appeal to the upper classes, whereas Mr Guppy already seems to sense how to handle high level clients and, with a little refinement, will ease his way into the corners of drawing rooms. I am always impressed with how he holds his ground with Mr Tulkinghorn in Ch 33 and 39, maintaining attorney-client privilege without committing himself and having a witness at hand to protect himself.

It would be nice to have a series of novels following the adventures of Inspector Bucket and his wife – a mash-up perhaps of Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple.

LikeLiked by 2 people

There’s something I forgot to mention in my previous comments. (Isn’t there always?) It has to do with this tribute Inspector Bucket pays Esther.

“When a young lady is as mild as she’s game, and as game as she’s mild, that’s all I ask, and more than I expect. She then becomes a queen, and that’s about what you are yourself.”

This might be an allusion to the biblical Esther, who could have reasonably been described as equally “game” and “mild” and, of course, became a queen. Then again, it might not be. The line makes sense either way.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I never thought about the implications of something before. George used to be somewhat close to Sir Leicester Dedlock in a master-and-servant kind of way and Sir Leicester offered a reward for the capture of Tulkinghorn’s murderer. It must have been painful for him to know that Sir Leicester was partly responsible for his incarceration and not be able to talk to anyone about it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

John O. Jordan’s exceptional little book “Supposing ‘Bleak House’” is a treatment and exposé of Esther, focusing not so much on Esther Summerson as on Esther Woodcourt, “as narrator and what it means for her to tell the story of her life, looking back on it as a married woman from the perspective of seven years” (3).

In Ch 4 – Endings, he says of Esther’s narrative and his interpretation of it:

“In the reading that I give to it, Esther’s narrative is a marvelous ghost story. It is a narrative full of contradictory impulses, containing passages of brilliant, powerful, hallucinatory prose, equal to the best that any Victorian novelist (even Dickens!) could produce, but also replete with coy evasions, sentimental self-indulgence, and a studied, almost masochistic desire to hide her beauty, sexuality, and creativity from the view of others and from herself. To the extent that generations of readers have found her ‘unlikable’ as a narrator, she has succeeded in this effort at concealment. My task in reading her otherwise has been to bring out the darker, more powerful and conflicted side of Esther’s character and to locate the sources both of her strength and of her neuroses, the two being closely connected. Esther’s struggle to give voice to her inner conflicts and to report on her descent into dark, terrifying regions of her psyche is heroic and deserves more respect than critics have generally been willing to accord it. Esther is fully the equal in this regard of Jane Eyre, Lucy Snowe, or Catherine Ernshaw, and ‘Bleak House’ deserves recognition as one of the great achievements in the tradition of the female gothic.” (72-73)

That “Bleak House” is a gothic novel should come as no surprise because it so obviously contains all the requisite elements. And, as Jordan says, it helps us understand Esther a little more and a little better. What follows is a primer to this genre based on Brendan Hennessy’s Introduction to his book, “The Gothic Novel” :

“The term ‘Gothic’ has three main connotations: BARBAROUS, like the Gothic tribes of the Middle Ages – which is what the Renaissance meant by the word; MEDIEVAL, with all the associations of castles, knights in armor, and chivalry; and the SUPERNATURAL, with the associations of the fearful, the unknown, and the mysterious”. (324, emphasis added)

In “Bleak House” we see examples of the BARBAROUS in the forms of Miss Barbary (her very name clues us in), Mr Tulkinghorn, Hortense, the brickmakers, the poverty of Tom-All-Alone’s, Mr Smallweed; of the MEDIEVAL in Chesney Wold and Sir Leicester Dedlock, Bleak House and Mr Jarndyce, Krook’s house, the Courts of Chancery; and of the SUPERNATURAL in The Fog, the Ghost’s Walk, spontaneous combustion, and Esther’s odd feeling before she actually sees Lady Dedlock for the first time in church.

Reading Hennessy’s list and description of milestones in the early development of the gothic genre is like reading a description of “Bleak House”:

(1) “The Castle of Otranto” (Walpole 1765) – The seminal gothic tale set the rubric for the genre to include (1) a mysterious setting such as a castle or a house, (2) “forces of nature to produce an atmosphere to indicate the mystery of life, the possibility of evil forces shaping man’s fate”, and (3) “stock characters” such as a “Byronic hero . . . the tyrant, the heroine, the challenger, the monk (there were to be both saintly and evil varieties), and the peasant who turns out to be noble”. (325-327) In “BH” – (1) London, Chesney Wold, Bleak House, the Courts of Chancery, Krook’s house, Tom-All-Alone’s; (2) the Fog, the snow and sleet; (3) Byronic hero = Richard; the tyrant = Mr Tulkinghorn; the heroine = Esther; the challenger = Mr Jarndyce, Gridley, Mr George; the saintly Monk = Mr Jarndyce, the evil Monk = Miss Barbary; the noble peasant = Jo, Guster, Jenny/Liz.

(2) “Vathek” (Beckford 1786) – “incorporated the fairy-tale exotic as well as terror” and is seen “as a parable on the theme” that one creates one’s own hell. (327-329) In “BH” – Nemo’s story, Gridley’s story, Miss Flite’s story, Richard’s story, Lady Dedlock’s story.

(3) “The Italian” (Radcliffe 1797) – “added poetry” (331). In “BH” – The text itself via the third person narrator and Esther’s portion.

(4) “The Monk” (Lewis 1796) – “used . . . scandalous accounts . . . to sensational and horrific effect” and made “a credible marriage of reality with the supernatural” and “added unusual and ‘real’ ghosts . . . whose restlessness is often ended when their bones are buried” (332). In “BH” – Lady Morbury Dedlock’s story and her haunting the Ghost’s Walk; Lady Honoria Dedlock is haunted by the ghost of her past; Jarndyce and Jarndyce haunting all the parties to it.

(5) “Northanger Abbey” (Austen 1818) – added satiric humor (335). In “BH” – Lord Boodle, et al, and the Right Honourable William Buffy, M.P., et al; Mrs Jellyby’s telescopic philanthropy; Mr Turveydrop.

(6) “Frankenstein” (Shelley 1818) – “the impulse behind it is the desire to show how dangerous the attempt to discover the secrets of life can be”; “The main message is . . . when reason is pushed to its limits, it breaks down; and the way in which the monster and his creator work toward each other’s destruction implies that balance is the key to virtue, sanity, and wholeness.”; it “expresses moral and political lessons as well as psychological truths” (329-330). In “BH” – The search for the “truth” of Jarndyce and Jarndyce, of Esther’s parentage, of Lady Dedlock’s secret.

Prichard’s essay “The Urban Gothic of ‘Bleak House’” does a terrific job exploring the ways “nearly every aspect of [‘BH’] can be seen as a highly original adaptation of Gothic convention for new literary purposes.” (432-433). I won’t try to condense his essay here, see below for a link to the full text. Of note however, because we’ve talked so much about it, is this comment on the dual narrative which points directly to the Gothic:

“. . . the complexity that results from the alternation between Esther’s first-person narration and the third-person narration is entirely in keeping with Gothic tradition: complicated use of multiple narrators was associated with the Gothic mode more than any other type of novel.” (450)

Dickens surely would have been aware of these works, and he was certainly an aficionado and author of ghost stories and supernatural tales. Indeed, I think if we look at almost any one (all?) of his novels we will find Gothic elements.

“The Urban Gothic of ‘Bleak House” by Allan Prichard: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1uZnFvoYzm_0yVx8R-4dQLA1vPLMpdcbl/view?usp=sharing

“The Gothic Novel: Introduction” by Brendan Hennessy: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1kLAxwkaSlCGQCrB8K6JCNLQhEysog4Y7/view?usp=sharing

LikeLiked by 3 people

Cool! I love the idea that Mr. Jarndyce is like the benevolent version of Miss Barbary. Both were going to be married at one point and wished to do so but decided against it for moral reasons. (Well, sort of.)

While he doesn’t exactly “create his own hell,” you could say that Krook creates his own destruction.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for posting this, Chris 🙂 It is utterly fascinating! It also gives lots of clues as to why things in Bleak House are as they are.

I have been rather lost in bewilderment about the ideas and ingredients which contributed to the genesis of this novel. It seems bursting at the seams with so much! In fact, just like Copperfield, it seems to contain much more than could be supposed from the word count alone! 😀

A commonality with other works such as you have analysed here is one of the factors which must account for this. Allusion is another factor, of course. Once again it feels like all of life is in there!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree with Rob…thank you, Chris!! LOVE the idea of BH as true to a gothic tradition, with nuanced versions of all its stock characters and settings! I’m going to be pondering this one!

LikeLiked by 1 person

A few responses to the following in Stationmaster’s comment:

“Speaking of Skimpole, I’ve heard he was modeled on the writer Leigh Hunt… Several characters from Bleak House are actually supposed to have been modeled on public figures Dickens… Laurence Boythorn was Walter Savage Landor… Dickens’s sister-in-law, Georgina Hogarth, thought Esther Summerson was based on herself.”

Forster, in The Life of Charles Dickens, has this to say

In [Bleak House] two characters appeared having resemblances in manner and speech to two distinguished writers too vivid to be mistaken by their personal friends.To Lawrence Boythorn, under whom Landor figured, no objection was made; but Harold Skimpole, recognizable for Leigh Hunt, led to much remark; the difference being, that ludicrous traits were employed in the first to enrich without impairing an attractive person in the tale, whereas to the last was assigned a part in the plot which no fascinating foibles or gaieties of speech could redeem from contempt.

Though a want of consideration was thus shown to the friend whom the character would be likely to recall to many readers, it is nevertheless very certain that the intention of Dickens was not at first, or at any time, an unkind one. He erred from thoughtlessness only. What led him to the subject at all, he has himself stated. Hunt’s philosophy of moneyed obligations, always, though loudly, half jocosely proclaimed, and his ostentatious wilfulness in the humouring of that or any other theme on which he cared for the time to expatiate, had so often seemed to Dickens to be whimsical and attractive that, wanting an “airy quality” for the man he invented, this of Hunt occurred to him; and “partly for that reason, and partly, he has since often grieved to think, for the pleasure it afforded to find a delightful manner reproducing itself under his hand, he yielded to the temptation of too often making the character speak like his old friend.”

If Dickens cast himself into one of the characters of Bleak House, I think he views himself as akin to John Jarndyce. Jarndyce’s liking for Skimpole may be an echo of those ‘whimsical and attractive’ qualities which Dickens admired in Skimpole’s original.

In a footnote, Forster provides an anecdote about Landor mentioning his unique laugh – rendered in the novel (and performed by Miriam Margolyes in her audiobook version superbly!!) Also the idea of burning a house to the ground makes it into the novel in an altered form:

It was at a celebration of [Landor’s] birthday in the first of his Bath lodgings, 35, St. James’s Square, that the fancy which took the form of Little Nell in the Curiosity Shop first dawned on the genius of its creator. No character in prose fiction was a greater favorite with Landor. He thought that, upon her, Juliet might for a moment have turned her eyes from Romeo, and that Desdemona might have taken her hair-breadth escapes to heart, so interesting and pathetic did she seem to him; and when, some years later, the circumstance I have named was recalled to him, he broke into one of those whimsical bursts of comical extravagance out of which arose the fancy of Boythorn. With tremendous emphasis he confirmed the fact, and added that he had never in his life regretted anything so much as his having failed to carry out an intention he had formed respecting it; for he meant to have purchased that house, 35, St. James’s Square, and then and there to have burnt it to the ground, to the end that no meaner association should ever desecrate the birthplace of Nell. Then he would pause a little, become conscious of our sense of his absurdity, and break into a thundering peal of laughter.

The point I made earlier about John Jarndyce being a version of Dickens in the novel is supported by this anecdote from Charles Dickens: A Life by Claire Tomalin

At this time [1843] he was engaged in one of his most admirable charitable endeavours, raising funds for the children of Edward Elton, an actor in Macready’s company, whose wife had died leaving him with six daughters and an eight-year-old son, and who was himself drowned at sea returning from an engagement in Hull. Dickens steamed into action, forming a committee, arranging a benefit, visiting the children and arranging for the eldest girl, Esther, to be given a place in a training college. Esther became a schoolteacher, as well as a virtual mother to her little sisters; one was helped to a musical career, one was found a position as a companion, one who was thought to be consumptive was sent to Nice, and the son became an actor like his father. Dickens remained active in helping them for many years… In 1861 Dickens was still writing to Esther, a full, affectionate and even intimate letter, long after she was married and a mother.

The Tragedy of the steamer, ‘Pegasus’ occurred in the early hours of 20th July 1843 on a journey from Edinburgh to Hull.

Tomalin later states:

He found in Esther Elton a ‘quiet, unpretending, domestic heroism; of a most affecting and interesting kind’, as he told Miss Coutts, and gave her name to Esther Summerson when he came to write Bleak House six years later.

LikeLiked by 2 people

A little more on Harold Skimpole:

A curious notion of Skimpole is presented in Lisa Jadwin’s 1996 article, Caricatured, Not Faithfully Rendered: Bleak House as a Revision of Jane Eyre (a very interesting and convincing article, especially if you like conspiracy theories and the like):

In Bleak House, Dickens encodes his disapproval of “bad” women writers in two characters who serve as examples to the apprentice memoirist Esther. The first is the filthy, inkstained and thus presumably impure Mrs. Jellyby who neglects her family to agitate on behalf of the African natives of Borrioboola-Gaa. The Jellyby family’s resentful testimony prompts Esther to condemn her

…if Mrs. Jellyby had discharged her own natural duties and obligations before she swept the horizon with a telescope in search of others, she would have taken the best precautions against becoming absurd (Chapter 38)

The second “bad” woman writer Esther meets comes, surprisingly, in the person of Harold Skimpole, the self styled “perfect child” who “never allude[s] to an unpleasant matter.” Though the reader may not consider him a “woman writer,” Skimpole is conventional femininity defamiliarized: his “simplicity, and freshness, and enthusiasm, and a fine guileless inaptitude for all worldly affairs” are distinctly feminine attributes, as are the “delicate face,” “sweet voice,” “perfect charm” and accomplishments (drawing, music, and conversation) that endear him to Jarndyce, who fondly “keeps” him by paying his debts. Initially Esther agrees that Skimpole’s “gay innocence” entitles him to financial support from those who “go after glory, holiness, commerce, trade.”Ultimately, however, “Skim/pole” reveals himself to be a “bad” woman: acquisitive, manipulative, calculating and deceitful. But to condemn this “amateur who might have been a professional” would be to denounce conventional femininity itself, for Skimpole’s gender and motives alone distinguish him from Ada Clare, Jarndyce’s other charming, helpless, decorative ward. Consequently Esther is much slower to denounce the “feminine” Skimpole than the “masculine” Mrs. Jellyby. Only when Skimpole reveals himself to be a writer—by publishing his memoirs—does Esther damn him outright:

[His diary and letters] showed him to have been the victim of a combination on the part of mankind against an amiable child. It was considered very pleasant reading, but I never read more of it myself than the sentence on which I chanced to light on opening the book. It was this: “Jarndyce, in common with most other men I have known, is the incarnation of selfishness.” (Chapter 56)

Those feminine attributes: “delicate face,” “sweet voice,” “perfect charm” and accomplishments (drawing, music, and conversation) are attributes which endear Dora Spenlow to David Copperfield. Indeed, Harold Skimpole’s many professions of being a “mere child” have more than a touch of Dora’s rationale in wishing to be thought of as a “child-wife”

‘I don’t mean, you silly fellow, that you should use the name instead of Dora. I only mean that you should think of me that way. When you are going to be angry with me, say to yourself, “it’s only my child-wife!” When I am very disappointing, say, “I knew, a long time ago, that she would make but a child-wife!” When you miss what I should like to be, and I think can never be, say, “still my foolish child-wife loves me!” For indeed I do.’ (DC 44)

Or to view it another way, would the following utterances of Skimpole seem out of place if spoken by Dora?

“you know what I am: I am a child. Be cross to me if I deserve it. But I have a constitutional objection to this sort of thing.”

“I am a child, you know! You are designing people compared with me…but I am gay and innocent; forget your worldly arts and play with me!”

“You’ll say it’s childish…Well, I dare say it may be; but I AM a child, and I never pretend to be anything else.”

Now, whether Dickens intended this effect or not, I don’t suppose we shall ever know. Yet there is a curious feature of Esther’s narration which goes some way to help the effect:

On Skimpole’s first appearance in Chapter 6, before we have any direct speech from Skimpole himself, Esther slips into a third person imitation of him. The indirect reported speech is ‘presented’ à la Skimpole with his words & quirkiness of expression but filtered through Esther’s voice – which can but accentuate any ‘feminine’ qualities, I suppose. These paragraphs of Esther in imitation of Skimpole crop up time and again – in fact in all but 2 ‘Skimpole’ chapters Esther ‘imitates’ Skimpole before he has direct speech of his own.

Here is a little sample from Chapter 8:

Mr. Skimpole was as agreeable at breakfast as he had been overnight. There was honey on the table, and it led him into a discourse about bees. He had no objection to honey, he said (and I should think he had not, for he seemed to like it), but he protested against the overweening assumptions of bees. He didn’t at all see why the busy bee should be proposed as a model to him; he supposed the bee liked to make honey, or he wouldn’t do it—nobody asked him. It was not necessary for the bee to make such a merit of his tastes. If every confectioner went buzzing about the world banging against everything that came in his way and egotistically calling upon everybody to take notice that he was going to his work and must not be interrupted, the world would be quite an unsupportable place.

In chapter 15, Esther’s imitations bookend the appearance of Skimpole. Before he speaks for himself. And then at the end of his appearance in a long paragraph about Gridly and Coavinses. It happens again in Chapter 18 and then in Chapter 31 – Esther is thus allowed to show slight changes in her mode of presentation as she changes her view of Skimpole’s nature.

A slight variation happens next time Skimpole appears in Chapter 37: Esther has indirect reported speech of Richard extolling the ‘dear old infant’ before a paragraph of her imitation of Skimpole which is followed by Skimpole speaking for himself:

“Was it Mr. Skimpole’s voice I heard?”

“That’s the man! He does me more good than anybody. What a fascinating child it is!”

I asked Richard if any one knew of their coming down together. He answered, no, nobody. He had been to call upon the dear old infant—so he called Mr. Skimpole—and the dear old infant had told him where we were, and he had told the dear old infant he was bent on coming to see us, and the dear old infant had directly wanted to come too; and so he had brought him. “And he is worth—not to say his sordid expenses—but thrice his weight in gold,” said Richard. “He is such a cheery fellow. No worldliness about him. Fresh and green-hearted!”

I certainly did not see the proof of Mr. Skimpole’s worldliness in his having his expenses paid by Richard, but I made no remark about that. Indeed, he came in and turned our conversation. He was charmed to see me, said he had been shedding delicious tears of joy and sympathy at intervals for six weeks on my account, had never been so happy as in hearing of my progress, began to understand the mixture of good and evil in the world now, felt that he appreciated health the more when somebody else was ill, didn’t know but what it might be in the scheme of things that A should squint to make B happier in looking straight or that C should carry a wooden leg to make D better satisfied with his flesh and blood in a silk stocking.

“My dear Miss Summerson, here is our friend Richard,” said Mr. Skimpole, “full of the brightest visions of the future, which he evokes out of the darkness of Chancery. Now that’s delightful, that’s inspiriting, that’s full of poetry! In old times the woods and solitudes were made joyous to the shepherd by the imaginary piping and dancing of Pan and the nymphs. This present shepherd, our pastoral Richard, brightens the dull Inns of Court by making Fortune and her train sport through them to the melodious notes of a judgment from the bench. That’s very pleasant, you know! Some ill-conditioned growling fellow may say to me, ‘What’s the use of these legal and equitable abuses? How do you defend them?’ I reply, ‘My growling friend, I DON’T defend them, but they are very agreeable to me. There is a shepherd—youth, a friend of mine, who transmutes them into something highly fascinating to my simplicity. I don’t say it is for this that they exist—for I am a child among you worldly grumblers, and not called upon to account to you or myself for anything—but it may be so.'”

Here the pattern ends. In both of the next chapters in which we come across Skimpole, he is found at his own house and speaks in his own voice when first we meet him.

Generally speaking, I think Skimpole is the only character that Esther imitates in this way – certainly for long passages.

The other narrator does it too, largely in the person of Jo… but that’s a whole other story 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person