WHEREIN WE REVISIT OUR first and second WEEK’S READING OF Hard Times (WEEKS 87-88 OF THE DICKENS CHRONOLOGICAL READING CLUB 2022-24); WITH A CHAPTER SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION WRAP-UP; CONTAINING A LOOK-AHEAD TO WEEKS three and four.

By the members of the Dickens Club, edited/compiled by Rach

Happy Week Three of Hard Times, friends! What is everyone thinking so far? Is Louisa a rebel, or has she been defeated by her upbringing? Will Sissy cave in too? Do we love to hate Bounderby, or is he just annoyingly despicable? What do we think of Stephen Blackpool?

- General Mems

- Hard Times, Book I, Chs 1-16 (Weeks 1 & 2): A Summary

- Discussion Wrap-Up (Weeks 1 & 2)

- A Look-Ahead to Weeks 3 & 4 of Hard Times (12-25 Sept, 2023)

General Mems

If you’re counting, today is Day 616 (and week 89) in our #DickensClub! This week and next, we’ll be beginning Hard Times, our nineteenth read of the group. Please feel free to comment below this post for the first and second week’s chapters, or use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter.

No matter where you’re at in the reading process, a huge “thank you” for reading along with us. Heartfelt thanks to our dear Dickens Fellowship, The Dickens Society, and the Charles Dickens Letters Project for retweets, and to all those liking, sharing, and encouraging our Club, including Gina Dalfonzo, Dr. Christian Lehmann and Dr. Pete Orford. Huge “thank you” also to The Circumlocution Office (on twitter also!) for providing such a marvellous online resource for us.And for any more recent members or for those who might be interested in joining: the revised two-and-a-half year reading schedule can be found here. If you’ve been reading along with us but aren’t yet on the Member List, we would love to add you! Please feel free to message Rach here on the site, or on twitter.

And for any more recent members or for those who might be interested in joining: the revised two-and-a-half year reading schedule can be found here. Boze’s wonderful introduction to our current read, Hard Times, can be found here. For other marvelous supplementary resources shared by Chris, please click here. And a friendly reminder that our marvelously gifted member, Rob Goll, has an audiobook version available, for the audiophiles among us!

If you’ve been reading along with us but aren’t yet on the Member List, we would love to add you! Please feel free to message Rach here on the site, or on twitter.

Hard Times, Book I, Chs 1-16 (Weeks 1 & 2): A Summary

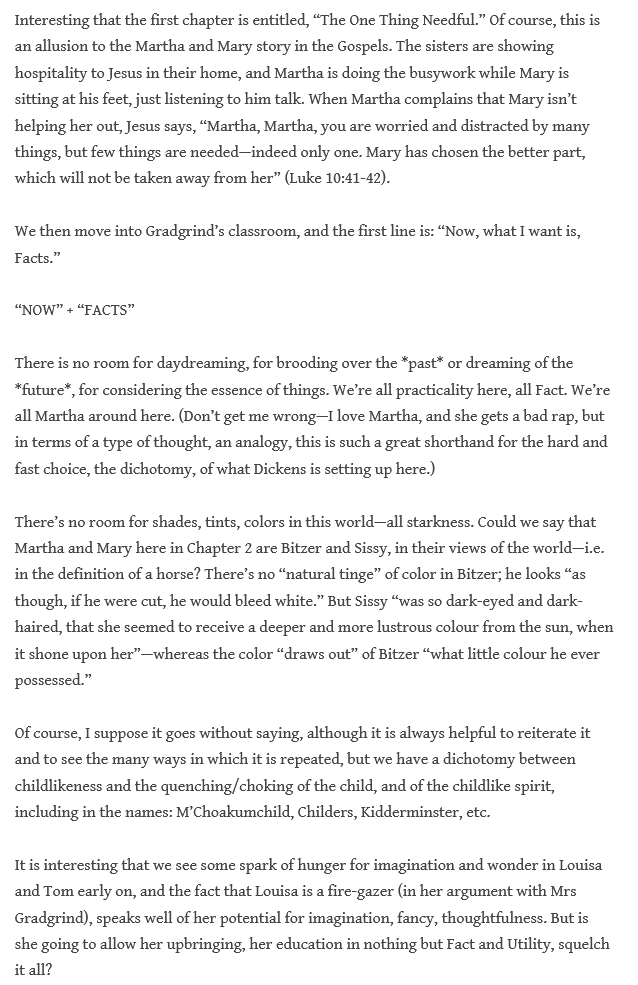

“Now, what I want is, Facts.”

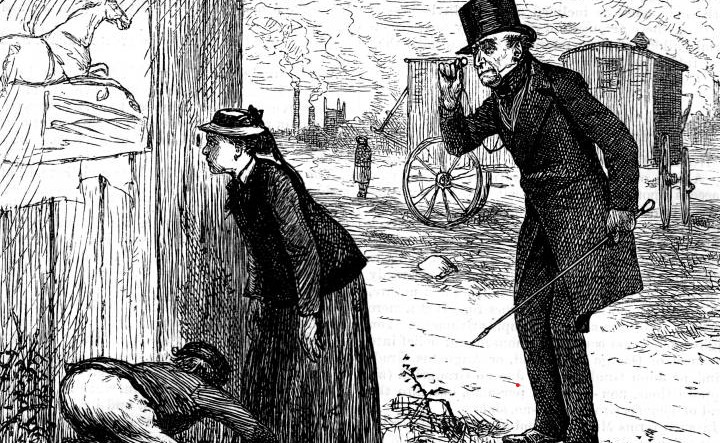

Thus we are introduced to the square-fingered Thomas Gradgrind, all squares and figures, who is addressing a classroom in his school (which he intends to be an educational model) to the schoolmaster, Mr M’Choakumchild. The school is compared to a factory; and situated in Coketown, “a town of red brick, or of brick that would have been red if the smoke and ashes had allowed it…a town of machinery and tall chimneys, out of which interminable serpents of smoke trailed themselves for ever and ever, and never got uncoiled.”

From the start, we see that Gradgrind’s whole educational philosophy centers around choking out all child-like things—all fancy, imagination, whimsy, art—to replace them with facts and figures and practicality. His foil in Chapter Two is Sissy Jupe (whom he insists on calling Cecilia—or “girl number twenty”—disapproving of nicknames as he does), whose father works with horses at the circus, and who cannot define a “horse.” Another student, Bitzer, defines it to Gradgrind’s satisfaction: “Quadruped. Graminivorous. Forty teeth, namely twenty-four grinders, four eye-teeth, and twelve incisive. Sheds coat in the spring; in marshy countries, sheds hoofs, too…”

Gradgrind’s own children, raised in a home called Stone Lodge, have been taught on the same principles.

“No little Gradgrind had ever seen a face in the moon; it was up in the moon before it could speak distinctly. No little Gradgrind had ever learnt the silly jingle, Twinkle, twinkle, little star; how I wonder what you are! No little Gradgrind had ever known wonder on the subject…”

Gradgrind visits the offending circus grounds, only to be shocked to see his children, Louisa and Tom, watching the action from a hiding place in their curiosity. Gradgrind wonders in indignation what his friend Mr Bounderby would say, if he saw Tom and Louisa acting so much like children.

And “who was Bounderby”?

“He was a rich man: banker, merchant, manufacturer, and what not. A big, loud man, with a stare, and a metallic laugh.”

Bounderby prided himself blusteringly on his humble background, of being “born in a ditch,” and on being a self-made man. He was “the Bully of humility.” Gradgrind approaches the subject of the “idle curiosity” that has led his own children to such a place as the circus grounds. They then discuss Cecilia Jupe, and how she managed to come to their school; Bounderby suggests taking her in hand right away, and forming her on the correct principles. Gradgrind knows the father’s address, and hopes Bounderby will accompany him. But before leaving, an awkward moment takes place when Louisa, a teenager on the cusp of young womanhood, is asked for a kiss by Bounderby, whom she clearly loathes. She says with apparent indifference that he may take a kiss is he likes, and he does so. After Bounderby leaves, she takes her handkerchief and rubs the spot on her cheek where he had kissed it, “until it was burning red.”

On the way to Sissy Jupe’s father at the inn called the Pegasus’s Arms, Gradgrind and Bounderby run into Sissy and Bitzer, as the latter is chasing Sissy with his attempts to try and help her define a horse. At the inn, Sissy’s father isn’t there, and while she goes to fetch him, Gradgrind and Bounderby meet a couple of the circus crew, Mr E.W.B. Childers and Master Kidderminster, who frustrate the gentlemen with all of their circus-related phrases that sound like so much fancy. Childers then tells Gradgrind that he thinks Sissy’s father has deserted her, having been “goosed” (hissed at) by the audience the previous night, and couldn’t bear the thought that Sissy would know of it. Bounderby protests that his own mother had run away from him, etc. Finally, Mr Sleary—of thick voice and thick frame and slurred speech—comes in, and seems to have some authority. Sissy comes in, heartbroken but justifying her father for having left on her own account, to do her some good, she believes.

Gradgrind then states his proposal to Sissy: “I am willing to take charge of you, Jupe, and to educate you, and provide for you. The only condition (over and above your good behaviour) I make is, that you decide now, at once, whether to accompany me or remain here. Also, that if you accompany me now, it is understood that you communicate no more with any of your friends who are here present.” With difficulty, thinking that her father would wish her to be educated, and knowing that if her father returns, Gradgrind will not try and venture any obstacle to her returning to him, she agrees, and makes a fond farewell of the company.

In the next chapter, we’re introduced to Mrs. Sparsit, a lady of noble lineage, but who has been attending upon Bounderby as a sort of dependent, and whose breeding Bounderby uses, in his blustering way, to be a contrast to his own humble background. In discussing Louisa—and wondering what sort of impression Sissy will make upon her, or whether the latter will be a bad influence upon her—it is made more obvious that Bounderby has some interest in Louisa beyond a friendly good will. Meanwhile, Sissy is to continue attendance at Gradgrind’s school, and be a help to Mrs Gradgrind.

Mrs Gradgrind wonders whether she ever should have had children. She chastizes Louisa for her tendency to wonder about things. Louisa and Tom also talk of Tom’s future at Bounderby’s bank, a destiny for which he is intended.

Nonetheless, Louisa can’t help but keep “wondering”—including about Sissy. As they get to know one another, Louisa proves to be such a good listener when Sissy talks of her past, and of her father. She still believes that he will return. Sissy, meanwhile, feels that she is not thriving in the school of Fact.

In chapter ten, we meet the poor power loom weaver, Stephen Blackpool, who meets his friend (and the woman he loves), Rachael, after work. She has taken pity on Stephen’s wife, a woman who is alcoholic, dissolute and unfaithful, and almost half-mad. His wife, though generally absent (with Stephen’s financial help), has come back, and is lying in his bed. He sees the care that Rachael lavishes on her, and the compassion she has, for the sake of their knowing one another from childhood, though Stephen (to his infinite regret) did not choose Rachael.

“The Fairy palaces burst into illumination, before pale morning showed the monstrous serpents of smoke trailing themselves over Coketown. A clattering of clogs upon the pavement; a rapid ringing of bells; and all the melancholy mad elephants, polished and oiled up for the day’s monotony, were at their heavy exercise again.”

Stephen then visits Bounderby (while Mrs Sparsit is present) to inquire about how the law can be of use to him in procuring a divorce from his alcoholic and unfaithful wife. Bounderby, full of blustering and theatrical indignation, essentially tells him that you need “a mint of money” to do so, and so it is feasible only for the very rich.

As Stephen leaves, dejected, he meets a mysterious old woman from out of town, who saves enough money to make the long journey into Coketown once a year only to glimpse Mr Bounderby, and to see the great success that he has had in the world.

Back at home, Rachael is nursing the sick wife, and insists that Stephen get some rest while she takes care of her that night. Upon waking at one point, only to see that his wife is about to take a dose of the medicine that might kill her, Stephen freezes, unable or unwilling to stop her. Rachael wakes at that moment, however, and snatches it out of her hand. Stephen is remorseful, and feels that Rachael is an angel.

Gradgrind, now an MP, is rather disappointed at Sissy’s progress at the school, but concedes that her attendance upon Mrs Gradgrind is so helpful that she may continue to live there. Tom then tries to convince Louisa of Bounderby’s interest in her, and that it would be a good thing to accept him, since then they—Tom and Louisa—could stay closer together and Louisa’s position would help Tom with his apprentice position at the bank (and, likely, in his dissolute habits).

When Gradgrind discusses Bounderby’s proposed marriage with Gradgrind’s 20-year-old daughter Louisa, he encourages her to consider the facts of the case only—not having any conception that love has anything to do with it. He lists the facts of the case, relevant statistics, and sees only the age disparity—50 and 20—as a possible consideration in the argument against the marriage. Louisa, drained of purpose and with a lack of training in any deeper motives for marriage (e.g. love), consents to the marriage.

Louisa is unmoved by Bounderby’s gifts, and finally only shows a spark of a last, desperate sort of emotion to Tom, as she fears that the step she is about to take (of marrying Bounderby) is a wrong-hearted and irrevocable one. But she goes through with it, and their honeymoon is to be in Lyons, where Bounderby hopes to observe some of the factory workings. Mrs Sparsit is clearly unimpressed by this marriage.

Discussion Wrap-Up (Weeks 1 & 2)

Miscellany & What We Loved; Hard Times on Audio

Several of us are listening to the marvelous audio narration of Hard Times by our member, Rob Goll, and loving it! Rob recalls it as the first of his “Lockdown recordings,” in 2020.

Childhood, Wonder, & Fairy-Tales: Hard Times as a Parable; Biblical Allusions & Onomastics

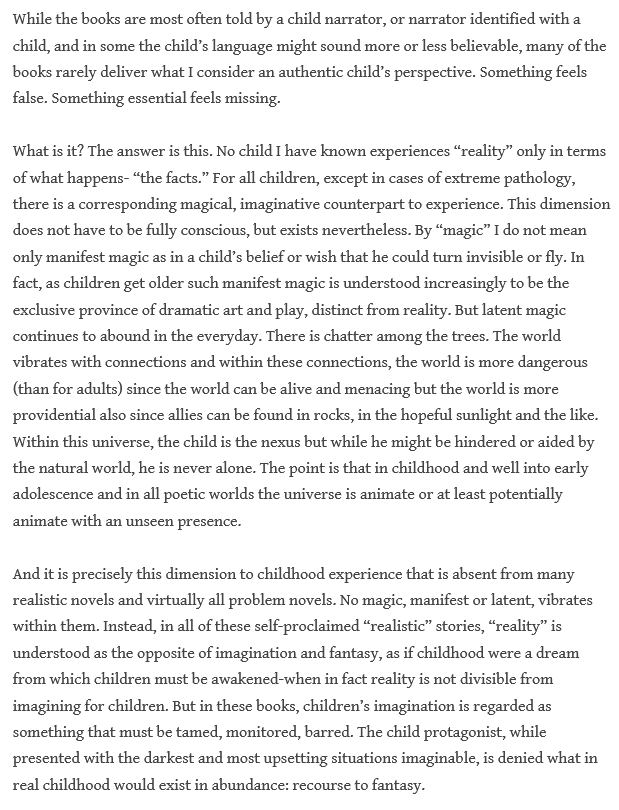

The Adaptation Statonmaster started out our discussion the week before last with a wonderful and very relevant quote from Barbara Feinberg’s memoir, Welcome Lizard Motel, of which I will share a portion here:

I commented on the Biblical allusions, setting up the Martha-Mary dichotomy of (as one might say) Fact and Fancy:

Rob responds, and with lots more insight into the trademark Dickensian naming of characters here:

Daniel makes more thought-provoking Biblical parallels, and discussed the wonderful emphasis in Rob’s reading:

Hard Times as a “Condition of England” Novel

Chris considers Hard Times in light of its status as a “Condition of England” novel:

The Stationmaster, quoting Chris, then responds:

“Never Wonder”: Mr Gradgrind Vs. Sleary’s Circus

The Stationmaster, echoes (with a dose of good humor) Chris’s sentiments about Mr Dombey, in wishing that we’d gotten more backstory on Gradgrind:

And his further consideration of Gradgrind:

Chris considers Gradgrind as “ripe for change,” and the circus as his ultimate, “glorious” foil:

Character Spotlight: Mr Bounderby

Is Bounderby a baddie we love to hate? Or is he just…painfully annoying? The Stationmaster tries to analyze his feelings about this character:

Chris adds, bringing in Mrs Sparsit:

The Women in Dickens

The Stationmaster compares Louisa’s consent to marrying Bounderby as echoing Juliet’s consent to marry Paris:

And Rob defends Dickens’s portrayal of womenhere:

“People Mutht Be Amuthed”; A Personal Account

Chris considers Hard Times as a “life affirming” text, and one which came just at the right time in her own journey:

Daniel reponds:

Some Questions to Ponder…

And here, I’ve highlighted a few questions that the Stationmaster and Rob brought up, for our consideration:

A Look-Ahead to Weeks 3 & 4 of Hard Times (12-25 Sept, 2023)

This week and next, we’ll be reading Book II, “Reaping” (Chs 1-12), of Hard Times. These chapters were originally published weekly, from 27 May to 15 July, 1854.

Feel free to comment below for your thoughts this week and next, or use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter.

If you’d like to read it online, you can find it at a number of sites such The Circumlocution Office; you can download it from sites such as Gutenberg.

I realize now in one of comments I referred to Dr. Strong from David Copperfield when I meant Mr. Creakle. That’s kind of embarrassing since the characters are opposites but it can’t be helped now.

I remember during our zoom meeting on Bleak House it was mentioned that Dickens disliked Jane Eyre because he considered the heroine too sassy, and Charlotte Bronte disliked Bleak House because she considered the heroine too sappy. Well, I was recently amused to discover that despite the books being seen (by their authors probably at any rate) as opposites, Susanna White directed (or codirected) adaptations of them both for the BBC. I find that a fun bit of ironic trivia.

While I’m on the subject, I thought I’d share a controversial opinion. I find Dickens to be a better writer of romance than the Brontes. It seems like in their books people are just in love with each other because their souls are entwined or something like that. It feels very random to me. In Dickens, characters falling in love with each other usually has to do with their characters and shared values. Of course, that doesn’t relate to either Bleak House, whose love story I’ve criticized for being undercooked, or Hard Times which has no positive romance except for the unconsummated love between Stephen and Rachael. Still, I can’t resist mentioning it.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I always find myself quite fascinated when it comes to Dickens and the Brontës. I find it odd that he claimed never to have read Jane Eyre or Wuthering Heights but I have my doubts. There is something about Lady Dedlock, first getting Jo to show her all the locations associated with her former lover, and then her seeking out his final resting place as her last desperate act after so many years had intervened, that has more than a touch of Heathcliff and Catherine about it.

I don’t think Charlotte disliked Bleak House itself, only that she found Esther unsatisfactory: ‘caricatured, not faithfully rendered,’ I believe she said.

Dickens during his many walks through London, employments, social engagements and other many activities, coupled with his remarkable capacity for observation provided him with so much in the way of raw materials for his writing compared with the limited experiences of the Brontë sisters in small village at the edge of the Yorkshire moors or in their various posts as governesses that in their defence we could say… but no, perhaps Charlotte Brontë says it better:

‘The eminent writers you mention—Mr. Thackeray, Mr. Dickens, Mrs. Marsh, etc., doubtless enjoyed facilities for observation such as I have not; certainly they possess a knowledge of the world, whether intuitive or acquired, such as I can lay no claim to, and this gives their writings an importance and a variety greatly beyond what I can offer the public.’

Letter to W.S. Williams 4th October 1847

again to W. S. Williams in September 1849, Charlotte writes:

I have read David Copperfield; it seems to me very good—admirable in some parts. You said it had affinity to Jane Eyre. It has, now and then—only what an advantage has Dickens in his varied knowledge of men and things!

Personally, I think that Dickens was so great at writing all about romance because he, just like David Copperfield, was so often ‘as enraptured a young noodle as ever was carried out of his five wits by love.’ 😀

LikeLiked by 2 people

I meant to write this in in a comment on last weeks’ reading but I forgot. Hope it’s OK now. Should we believe Louisa is telling the truth when she says it was, she who brought Tom for a peep at Sleary’s show? Or is she lying to protect him? Either possibility would be in character for her.

Harthouse’s seduction or attempted seduction of Louisa is fascinating. We’ve had seducers in Dickens before, mainly Jingle, Carker and Steerforth, but it’s always been easy to see (and more implied than shown) how their victims (Miss Rachael, Edith and Emily) could fall for them since they were all, in their individual ways, very emotional characters. The seemingly stoic Louisa would seem to provide more of a challenge. I suspect it’s this challenge even more than her beauty that attracts Harthouse. It’s disturbing and, granting a certain amount of melodrama, plausible how he finds her one “weakness” and exploits it for all it is worth. (I put “weakness” in quotation marks because it’s depressing to think of Louisa loving someone as being a bad thing.)

Louisa is a great character. I don’t love her quite as much as the similar characters of Edith from Dombey and Son and Estella from Great Expectations. Maybe it’s because she’s the one who’s portrayed as the most purely a victim of her upbringing and lacks their relative moral agency.

What makes Tom Gradgrind Jr. fairly unique among Dickens’s bad guys is that he’s not creepy or funny (unless you count him telling Mrs. Sparsit “Loo’s not likely to think of you unless she sees you.”) He’s just an ordinary run of the mill jerk. You could say that Steerforth was also like that, and Henry Gowan in Little Dorrit will be too. But they have a certain Byronic or pseudo-Byronic flair. There’s nothing charismatic or romantic about Tom unless you count his Gradgrindian upbringing.

It was an interesting decision on Dickens’s part to make Mrs. Gradgrind a prophetess on her deathbed (“But there is something—not an Ology at all—that your father has missed, or forgotten, Louisa. I don’t know what it is… I shall never get its name now. But your father may.”) when she’s been a whiny useless character up till then. Useless to the other characters, I mean. She’s been useful to the readers in providing comic relief. After all, “people mutht be amuthed.”

As thrilling as the scene of Mrs. Sparsit tracking Louisa and Harthouse in Chapter 11 is, it’s always “amuthing” to see the ultra-dignified character creepy through the shrubbery, getting “prickly things in her shoes” and caterpillars in her dress.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I love “Hard Times” and think it’s so underrated. It’s one of my top five Dickens. And I agree with Rob about the portrayal of women being exceptionally strong here.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Really love Hard Times, and on each reading I find something more. I think what is striking me more and more is how much of a Miltonist Dickens was. Stephen’s views on misfortnet marriages echo what Milton was writing in the 1640s about divorce, and in the context in which Dickens was writing amply demonstrate his political views on that issue, even if he wasn’t able to directly articulate them.

I’ve been thinking rather a lot about the female characters, particularly Mrs Blackpool and I am particularly interested in the contextualisation of her given the ongoing debate about divorce law reform at the time. I have more to say on this – a lot more.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I’d love to hear more on this, Deborah! And speaking of Mrs Blackpool, and also referencing the Brontes as the Stationmaster has done above, is she influenced perhaps by Mrs Rochester? Not that we get to “see” either character very much–but they both serve as a “case study” in regard to the marriage laws.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I feel like the character of Mrs. Rochester is more potentially sympathetic. While she’s described as similar to Stephen’s wife in being a promiscuous alcoholic, the fact that she has to be locked up all the time makes it possible, though not inevitable, for readers to pity her. Mrs. Blackpool doesn’t have a lot of mobility, being passed out for most of when we see her, but she has relatively more than her Jane Eyre counterpart.

LikeLike

I know now that the thing I forgot to ask in another comment (about whether Louisa really was the one who brought Tom to Sleary’s) I really did remember. Sorry for being repetitive. Can’t be helped now.

I’d like to share another excerpt from Welcome to Lizard Motel by Barabara Feinberg. This one may not seem relevant to Hard Times as the one last one did but I promise it does.

“What is the ideal child like now, I wonder? I wonder. ‘Independent,’ I answer myself instantly…’a real trooper.’

What exactly do I mean by that? It used to be a compliment. We used to say it so admiringly, ‘we’ being my friends and I who worked as daycare teachers in the late 1970s and through the 80s. I bet we, and others in daycare, coined the term, at least as applied to children. We said it about a child who’d come through another long day-who was surviving the turbulence of family life, being dropped off at 7:00 a.m. by a parent on his way to work, some who’d already worked a night shift. Or by a single parent, valiant, exhausted, other children in tow, all facing the day. Or by an adult who’d been up all night drinking. The child came downstairs to the church basement, where the daycare was located, and stayed there for twelve hours. ‘But you know what?’ we’d say to each other with respect. ‘Through all this, he’s a real trooper…’

A ‘real trooper’ had sass, resilience. He was the opposite of a kvetch, or a child spoiled or petted or indulged, or one who was ‘too sensitive.’ That was a lilywhite octopus of a child who needed to be toughened up. (Secretly I knew I had been such a child.) A ‘trooper’ didn’t cling, didn’t talk baby talk, didn’t suck his thumb…

As kind and sensitive as we strove to be, was it right for such young children to spend their childhoods in these long, slightly orphaned days? What would the ramifications of this situation be? …And what was so good about children not clinging, not sucking their thumbs? Weren’t these expressions of one’s desire not to leave, not just yet? Didn’t young children have the right to express this? When we admired the troopers, were we celebrating for our own convenience? The trooper was no work, made us feel like we were doing fine; the octopus, on the other hand, was hell. The trooper played us back to ourselves as doing it all right, whereas the unhappy child, who longed for Mother and peed in his cot at naptime and showed signs of coming apart at the seams, made the whole daycare thing seem shabby and a failure and wrong.

Just as adults had to work, no kid got a free ride. (Were we starting to think of childhood itself as a ‘free ride?’) Kids had their job too: Going To Daycare Without Too Much Fuss.”

It sounds like Bounderby expects his mill hands to be “real troopers.”

LikeLiked by 3 people

Oh my. That’s hard-hitting.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think it very appropriate that Mrs Sparsit’s handicraft should be netting. I considered calling it her hobby, her art, her pastime, her work, her busywork – all of which are appropriate and add nuance to what it is she is doing. Setting traps, at least mental ones, for those she watches (spies upon?). I like the almost off-hand comment regarding her snooping, “Further, she was lady paramount over . . . scraps of paper torn so small, that nothing interesting could ever be deciphered on them when Mrs Sparsit tried.” (Bk 2, Ch 1), and of her in general, “It soon appeared that if Mrs Sparsit had a failing in her association with that domestic establishment, it was that she was so excessively regardless of herself and regardful of others, as to be a nuisance.” (Bk 2, Ch 8)

I was reading an article (“The Rhetoric of ‘Hard Times’” from Language of Fiction by David Lodge) which takes exception to Dickens’s appropriating Harthouse’s term “whelp” for Tom. Lodge says: “But in the case of Harthouse’s ‘whelp’ [Dickens] has taken a moral cliche from a character who is morally unreliable, and invested it with his [Dickens’s] own authority as narrator. . . . ‘the whelp’ . . . acts merely as a slogan designed to generate in the reader such a contempt for Tom that he will not enquire too closely into the pattern of his moral development”. (155) This label, Lodge says, “forced [Tom] into a new role” of villain from his original role as a victim of Gradgrind’s Fact-based education. But I think that Tom’s downward trajectory can be seen as a result of his upbringing. The well-established cycle of kids rebelling against their upbringing puts Tom in line for getting into debt through dissipation – having been constrained in his youth from having “fun”, he now invariable falls into exploring all those things he was never allowed to do while under the parental thumb. That he should get into debt is no surprise, that there should be no “great amount of confidence . . . established between himself and his most worthy father” or “his highly esteemed brother-in-law’ (Bk 2, Ch 7) is also no surprise. Nor that he should pinch his sister for relief. Tom IS a whelp – both in it’s meaning of a young dog and as a cry for help – and perhaps, in the crush to write and publish, Dickens just didn’t land on the word until it fell out of Harthouse’s mouth.

Harthouse seems to me to be a version of Richard Carstone, but with money and no judgment hanging over his head, in that he flits from occupation to occupation, lives in perpetual boredom and fails to appreciate the advantages he has and uses them for ill-considered purposes. Poor Louisa is an easy target for him. She, like her brother, has no experience of the real world or the ways of cads.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I thought Dickens was foreshadowing Tom’s villainy all the way back in Chapter 9. It doesn’t feel forced to me either.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have always felt that the narrator adopting Harthouse’s ‘whelp’ is a brilliant touch!

LikeLike

Chris, your first paragraph here, beautifully summarised (as you always seem able to do) doesn’t half show many ways in which Mrs Sparsit with her netting, foreshadows Madame Defarge with her knitting!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

The scene of the Union meeting in Chapter 4 is fascinating in that it’s sort of the reverse of what I described Dickens as doing with Sir Leicester Dedlock in Bleak House. Dickens clearly agrees with the striking workers or at least agrees with their ultimate goals and is opposed to their enemies, but he really doesn’t approve of the way they ostracize Stephen Blackpool. It’s a very nuanced scene, so nuanced that I’m not sure it totally works. It’s hard to credit that the Union members could be both as noble and admirable as Dickens describes them as being and also as easily manipulated by Slackbridge. The story might have been more convincing if Dickens wholeheartedly endorsed the organization and depicted Slackbridge as a hero or alternatively made the workers villains, though the latter would certainly require a radical rewrite of the book’s message. Still, the scene is interesting as fairly dramatically compelling as it is.

I commented before about Harthouse’s seduction of Louisa, but I didn’t mention Mrs. Sparsit’s seduction of Bounderby, how she positions herself as a superior alternative to his wife. Bizarrely, it feels like the rakish Harthouse and the prim Mrs. Sparsit are working in tandem to the ruin the Bounderbys’ marriage. I mean, they’re not really working together since part of Mrs. Sparsit’s goal is to expose Harthouse and get him in trouble but they kind of are working together.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Mrs Sparsit calls Louisa “Miss Gradgrind” rather than “Mrs Bounderby” quite the same way and with the same belittling intention as Uriah Heep continued to call David “Master Copperfield”. Such blatant insolence made to appear somehow endearing.

And I agree with Stationmaster in that I think she is as much to blame for the rift between Louisa and Mr Bounderby as is Harthouse. She works on Mr Bounderby’s ego and feelings quite as much as Harthouse works on Louisa’s. They both watched and discovered exactly which buttons to push and are highly skilled at pushing them.

Mr Gradgrind is such a poor example for his children – he doesn’t return home from London until AFTER his wife’s death, and then stays just long enough to bury her. Such feeling! The poor woman is perhaps – would love to research this at some future date – one of the finest examples of the result of gaslighting in literature. I am pleased, however, to see Louisa having so much compassion for her mother. This is another example – along with her love for her brother and the charity she showed toward Stephen Blackpool in Bk 2 Ch 6 – of Louisa’s “better angel” side (Bk 2 Ch 12).

Her “better angel” also takes care of her when Harthouse seeks to seduce her. She doesn’t know if she loves him, but she does know that she hates her husband and that her marriage to Boundary is over. She doesn’t know how to respond to Harthouse but she does know that to actually run away with him would be disastrous BECAUSE she doesn’t know how to respond. He is “a man such as I had had no experience of”. Her inexperience with wonder and fancy and her former philosophy of “what does it matter?” have left her with nothing to draw upon for guidance and thus she returns to her father begging him to “Save me by some other means!” (Bk 2 Ch 12)

Regarding Slackbridge and the Strike – they seem to fill two functions: 1) they allow Dickens to comment on trade-union agitators and strikes, and 2) they are a plot device to separate Stephen Blackpool from the other workers. Dickens’s position on strikes seems to be that if Masters and Men would just get together and realize they are working for the same end they could come to some compromise that would be beneficial to both sides – easier said than done. On agitators, I think Dickens has no time for them just as he has no time for the Chadband’s or Stiggins’s. They are manipulators who really don’t care about those they are manipulating, rather they are working for their own ends which are less than admirable.

As for Stephen’s refusal to join the strike – he stays out of it because he made a promise to Rachael, but I’m having trouble locating just where in the novel he does this – help please! Is it in Bk 1 Ch 10 when he tells Rachael “thy word is law to me” and Rachael says, “Let the laws be”? Or is it in Bk 1 Ch 13 when he kneels before Rachael after she saves his wife from drinking poison? Or is it implied and then told to us when Stephen addresses the workers (Bk 2 Ch 4) and then talks with Bounderby (Bk 2 Ch 5) and again when Louisa talks with Rachael (Bk 2 Ch 6)? If Rachael’s request to Stephen was, as she tells us in Bk 2 Ch 6, for “him to avoid trouble for his own good”? If the latter, then the best way for him to do so would probably have been to join the strike and stick with his fellow workers. I don’t understand why Stephen would think Rachael would be against his joining the strike, after all, isn’t she also one of the Hands and wouldn’t SHE join the strike as well? Or does she do some other kind of work, or maybe she doesn’t work for Bounderby, or are the women exempt from or not part of the strike for some reason?

And — I think it curious that Stephen says to Rachael, “thy word is a law to me” (Bk 1 Ch 10) and then Mrs Sparsit says to Bounderby, “your will is to me a law, sir” (Bk 2 Ch 11) [earlier regarding Bounderby’s request that she make his breakfast in place of the late-appearing Louisa we are told “that she had taken the liberty of complying with his request: long as his will had been a law to her” (Bk 2 Ch 9]. It is also curious that for Stephen it is Rachael’s “word” that is law whereas for Mrs Sparsit it is Bounderby’s “will”. Both Stephen’s and Mrs Sparsit’s trajectories are governed by how they perceive someone else would want them to act or by what someone else would want. But the words and will of others are often misunderstood. We have already seen the consequences of Stephen’s interpretation of Rachael’s words, and have now to wait to see those of Mrs Sparsit’s interpretation of Bounderby’s will.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I always assumed Stephen made the promise to Rachel offstage. I don’t really get the motivation either. Presumably, she (rightly) figured that joining the strike would get him in trouble with Bounderby, but she didn’t anticipate the trouble it would get him into with his coworkers, presumably since there hadn’t been strikes like this before in Coketown. Stephen’s big speech in Chapter 5 though really makes it sound like he’s had experience with these things or at least with people like Slackbridge.

I think the reason Rachel isn’t expected to join the United Aggregate Tribunal is that its members are all male. (Slackbridge addresses them in terms like “brothers.”) It does seem though that the women workers at Bounderby’s mill are unofficially supporting the strike since Stephen worries that Rachel’s coworkers will shun her if she supports him.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Could you expound on why you’d describe Mrs. Gradgrind as being gaslit?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Perhaps I’m not using the term “gaslighting” correctly, but I think Mrs Gradgrind fits this definition – “Gaslighting is a form of psychological abuse in which a person or group causes someone to question their own sanity, memories, or perception of reality. People who experience gaslighting may feel confused, anxious, or as though they cannot trust themselves.” (MedicalNewsToday.com)

Mrs Gradgrind is subdued, corrected, stunned, reproofed, frowned at, talked at, unminded – all within Bk 1 Ch 4. She is described as “a little, thin, white, pink-eyed bundle of shawls, of surpassing feebleness, mental and bodily; who was always taking physic without any effect, and who, whenever she showed a symptom of coming to life, was invariably stunned by some weighty piece of fact tumbling on her” and as “weakly smiling, and giving no other sign of vitality, looked (as she always did) like an indifferently executed transparency of a small female figure, without enough light behind it.”

The only history we are given of her is – “In truth, Mrs. Gradgrind’s stock of facts in general was woefully defective; but Mr. Gradgrind in raising her to her high matrimonial position, had been influenced by two reasons. Firstly, she was most satisfactory as a question of figures; and, secondly, she had ‘no nonsense’ about her. By nonsense he meant fancy; and truly it is probable she was as free from any alloy of that nature, as any human being not arrived at the perfection of an absolute idiot, ever was.” Her being “satisfactory as a question of figures” is explained in Simpson’s “Companion to Hard Times” as “referring to [her] healthy financial state before she married Mr Gradgrind. All her property after marriage would legally have become her husband’s.” (75) I would also submit that perhaps, as a double entendre, she may have been somewhat buxom.”

In Bk 2, Ch 9 as she lay dying and Louisa comes to see her: “I want to hear of you, mother; not of myself.” she responds, “You want to hear of me, my dear? That’s something new, I am sure, when anybody wants to hear of me.” Her last words question the existence she has been forced to live in since her marriage: “But there is something—not an Ology at all—that your father has missed, or forgotten, Louisa. I don’t know what it is. I have often sat with Sissy near me, and thought about it. I shall never get its name now. But your father may. It makes me restless. I want to write to him, to find out for God’s sake, what it is. Give me a pen, give me a pen.” They are words of wisdom that would have been subdued, corrected, stunned, reproofed, frowned at, talked at, unminded if she had actually been able to write to or ever spoke them aloud to her all knowing, factual husband.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Chris, I’ve been trying to find the passage too–Rachael’s prohibition to Stephen–and without success. (It is odd how I almost feel I have a “memory” of it, as though it had happened!) But during the whole bit about “let the laws be,” it is implied that she is afraid, as though they’ve been over this territory before, whether about the marriage laws, or strikes, or what not. It could be read as though Stephen has a bit of a history of bringing some trouble on himself, that she is worried about…? But he’s certainly been at the factory for quite a while, so…who knows. I agree with the Stationmaster that it seems to be something that has happened “offstage,” and only implied by Rachael’s fear of his getting involved in controversial doings.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah! The elusive promise that Stephen made! I think I may be able to shed some light.

Stephen’s promise to Rachael is a very simple one. He gave her his promise and being an honest man and an honourable man he kept to his promise.

In the original manuscript and the corrected proofs the relevant passage was in Book 1, Chapter 13 “Rachael” The passage was not, however included in the final version on the grounds that it might prove unpopular with readers of a certain demographic ( mill owners, most likely… so I believe anyway)

This is the deleted passage:

“Thou’st spoken o’ thy little sisther. There agen! Wi’ her child arm tore off afore thy face!” She turned her head aside, and put her hands to her eyes. “Where dost thou ever hear or read o’ us—the like o’ us—as being otherwise than onreasonable and cause o’ trouble? Yet think o’ that. Government gentlemen comes down and mak’s report. Fend off the dangerous machinery, box it off, save life and limb; don’t rend and tear human creeturs to bits in a Chris’en country! What follers? Owners sets up their throats, cries out, ‘Onreasonable! Inconvenient! Troublesome!’ Gets to Secretaries o’ States wi’ deputations, and nothing’s done**. When we do get there wi’ our deputations, God help us! We are too much int’rested and nat’rally too far wrong t’have a right judgement. Haply we are: but what are they then? I’ th’ name o’ th’muddle in which we are born and live and die, what are they then?” “Let such things be, Stephen. They only lead to hurt. Let them be!” “I will, since thou tell’st me so. I will. I pass my promise.”

** In the corrected proofs, a footnote was inserted here: “See Household Words vol. IX page 224, article entitled “Ground in the mill.”

This article, written by Henry Morley appeared in the issue which contained Chapters 7 and 8 of Hard Times. It is a beautifully written but quite grim article on industrial accidents. and provides background context for elements of the above passage.

It can be read here:

https://www.djo.org.uk/household-words/volume-ix/page-224.html

The hard-hitting opening paragraph gives a clue as to what happened to Rachael’s little sister.

“It is good when it happens,” say the children,—”that we die before our time.” Poetry may be right or wrong in making little operatives who are ignorant of cowslips say anything like that. We mean here to speak prose. There are many ways of dying.

Perhaps it is not good when a factory girl, who has not the whole spirit of play spun

out of her for want of meadows, gambols upon bags of wool, a little too near the

exposed machinery that is to work it up, and is immediately seized, and punished by the merciless machine that digs its shaft into her pinafore and hoists her up, tears out her left arm at the shoulder joint, breaks her right arm, and beats her on the head. No, that is not good; but it is not a case in point, the girl lives and may be one of those who think that it would have been good for her if she had died before her time.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Gosh! Rob, thank you for this–that is so illuminating! (And horrifying.) It really helps give context. It almost seems a “continuity error,” the omission from the final work. I wish it had stayed in

LikeLiked by 1 person

p.s. Sorry if I’ve been a bit quiet during this portion, friends! Boze is returning to Texas for a couple of months tomorrow, & will be leaving not long after the wrap-up posts. So, we’ve had some “hard times” over here trying not to think of it!

On another note, we’d talked in the last Zoom chat about the possibility of doing the HT Zoom on Sat, October 14th…does that still sound okay? I’ll put a note on it in the General Mems part of the wrap, and will send out the Zoom link to the emails I have listed sometime during this final section of HT.

And, this is looking a bit ahead, but just food for thought: We’ll have a full 2 months for our next read, Little Dorrit, which I believe is Oct 24 to Dec 18. But if we wait until the following Saturday for the wrap-up, that’s awfully close to the holidays. Perhaps we can look at some other dates during the break. I’ll bring this up in our next Zoom meet!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think I am working on the 14th … but I can probably join for a while like I did on the last one.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have always thought that the in-a-nutshell description of Bounderby in Book 1, chapter 4 is one of Dickens’ greatest in so vividly drawing a character’s appearance and behaviour. It is so good that I make no apologies for popping it down here before I get to the point I wanted to make with reference to this fortnight’s section 😊

He was a rich man: banker, merchant, manufacturer, and what not. A big, loud man, with a stare, and a metallic laugh. A man made out of a coarse material, which seemed to have been stretched to make so much of him. A man with a great puffed head and forehead, swelled veins in his temples, and such a strained skin to his face that it seemed to hold his eyes open, and lift his eyebrows up. A man with a pervading appearance on him of being inflated like a balloon, and ready to start. A man who could never sufficiently vaunt himself a self-made man. A man who was always proclaiming, through that brassy speaking-trumpet of a voice of his, his old ignorance and his old poverty. A man who was the Bully of humility.

A year or two younger than his eminently practical friend, Mr. Bounderby looked older; his seven or eight and forty might have had the seven or eight added to it again, without surprising anybody. He had not much hair. One might have fancied he had talked it off; and that what was left, all standing up in disorder, was in that condition from being constantly blown about by his windy boastfulness.

I absolutely love that this last mentioned feature of his windy nature is carried through to Book 2 and his interview with Stephen in Chapter 5, “Men and Masters”

Mr. Bounderby, who was always more or less like a Wind, finding something in his way here, began to blow at it directly.

The wind began to get boisterous.

‘Not to me, you know,’ said Bounderby. (Gusty weather with deceitful calms. One now prevailing.)

…said Mr. Bounderby, now blowing a gale

…said Mr. Bounderby, by this time blowing a hurricane

😀

LikeLike

On the subject of children of the mills, I found a beautiful song sung by Lancashire workers which is called The Hand Loom Weavers Lament – the earliest reference I came across was from the 1880s but it is easy to imagine it came from much earlier:

When we look on our poor children, it grieves our hearts full sore.

Their clothing it is worn to rags, while we can get no more.

With little in their bellies, they to work must go,

Whilst yours do dress as manky as monkeys in a show.

You tyrants of England! Your race may soon be run.

You may be brought unto account for what you’ve sorely done.

LikeLike