WHEREIN WE REVISIT OUR third and fourth WEEK’S READING OF Hard Times (WEEKS 89-90 OF THE DICKENS CHRONOLOGICAL READING CLUB 2022-24); WITH A CHAPTER SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION WRAP-UP; CONTAINING A LOOK-AHEAD TO WEEKS five and six–our final weeks with Hard Times.

(Banner image: by Harry French, 1877. Scanned image Philip V. Allingham for Victorian Web.)

By the members of the Dickens Club, edited/compiled by Rach

Happy Week Five of Hard Times, friends! Your co-hosts admit that we have our own “Hard Times” as Boze leaves Oregon today to return to Texas for a couple of months–thus, a certain Pickwickian light has gone out of the house! So, if we have been a little quiet in the discussion in Weeks 3 & 4, that is part of it…

But what marvelous insights have been shared this week–particularly on the women in the novel.

But first, a few quick links:

- General Mems

- Hard Times, Book II, “Reaping,” Chs 1-12 (Weeks 3 & 4): A Summary

- Discussion Wrap-Up (Weeks 3 & 4)

- A Look-Ahead to Weeks 5 & 6 of Hard Times (26 Sept to 9 Oct, 2023)

General Mems

If you’re counting, today is Day 630 (and week 91) in our #DickensClub! This week and next, we’ll be finishing Hard Times, our nineteenth read of the group. Please feel free to comment below this post for the fifth and sixth week’s chapters, or use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter.

SAVE THE DATE: We’re looking at Saturday, 14 October for our Zoom discussion of Hard Times at 11am Pacific (US)/2pm Eastern (US)/7pm GMT (London). Very informal chat–tell us what you loved (and didn’t!) about Hard Times. Prior to the meeting, we’ll have a poll on here in anticipation of the Little Dorrit meeting–as it is such an important work, but its end falls near the holidays.

No matter where you’re at in the reading process, a huge “thank you” for reading along with us. Heartfelt thanks to our dear Dickens Fellowship, The Dickens Society, and the Charles Dickens Letters Project for retweets, and to all those liking, sharing, and encouraging our Club, including Gina Dalfonzo, Dr. Christian Lehmann and Dr. Pete Orford. Huge “thank you” also to The Circumlocution Office (on twitter also!) for providing such a marvellous online resource for us. And for any more recent members or for those who might be interested in joining: the revised two-and-a-half year reading schedule can be found here. If you’ve been reading along with us but aren’t yet on the Member List, we would love to add you! Please feel free to message Rach here on the site, or on twitter.

And for any more recent members or for those who might be interested in joining: the revised two-and-a-half year reading schedule can be found here. Boze’s wonderful introduction to our current read, Hard Times, can be found here. For other marvelous supplementary resources shared by Chris, please click here. And a friendly reminder that our marvelously gifted member, Rob Goll, has an audiobook version available, for the audiophiles among us!

If you’ve been reading along with us but aren’t yet on the Member List, we would love to add you! Please feel free to message Rach here on the site, or on twitter.

Hard Times, Book II, “Reaping,” Chs 1-12 (Weeks 3 & 4): A Summary

That “dragon” of Bounderby’s bank, Mrs Sparsit, talks to the model Gradgrindian pupil (a kind of anti-Sissy-Jupe, if you recall…) and bank porter, Bitzer, about the dissolute Tom Gradgrind. A stranger, Mr Harthouse, enters, and has come on business. The conversation turns to the intriguing young wife of Bounderby, Louisa. Harthouse, careless and seeking some sort of amusement or focus, is intrigued by Gradgrind’s philosophy and is invited to dinner at the Bounderbys’ home, where he makes a favorable impression on Tom.

Later, Tom and Harthouse talk about Louisa, and how the marriage to Bounderby came about. Mr Harthouse appears unduly intrigued by her, and by the idea that having a claim on her affections would be something to offset his usual careless boredom.

Meanwhile, under the leadership of the blustering Slackbridge, factory hands have unionized—all except for Stephen Blackpool, who only wants to work. Blackpool is shunned by his fellow laborers, and Bounderby sends for Stephen, hoping that he has enough sympathy to give Bounderby an update on the union meeting. But Stephen doesn’t want to take sides, and is unaccommodating. Bounderby fires him, forcing Stephen to look elsewhere for work.

After this dismal meeting, Stephen and Rachael encounter the woman they had met before, who says that her name is Mrs Pegler. They all have tea together at Stephen’s lodgings, and then have a surprise visit from Louisa and Tom. Louisa, who had been sorry for Stephen at his encounter with Bounderby, offers money to Stephen to help him on his way as he searches for other employment. Stephen accepts only a small portion of the money, which he will pay back. Later, Tom takes Stephen aside and says that he might be able to help Stephen in another way, too, though this is as yet uncertain; Tom instructs Stephen to remain waiting near the bank for the next few nights. Stephen does so, but hears nothing more from Tom. However, several people—including Mrs Sparsit and Bitzer—watch him.

Stephen leaves Coketown in distress at leaving Rachael.

Back at Bounderby’s, Louisa and James Harthouse are much more in one another’s company, and Harthouse, seeing that Tom is the subject of all her care, uses his influence over Tom to try and change Tom’s careless, ingrateful attitude towards Louisa. Louisa realizes that Harthouse sees her as no one else appears to do, and understands her heartache about Tom’s ingratitude.

Stephen’s hanging around the bank at night has had the effect of making him the prime suspect in a robbery at Bounderby’s bank—of 150 pounds. His leaving Coketown is seen as another proof of his guilt. Louisa’s fear is that Tom is actually the culprit—but Tom will not confide in her, and lies.

Mrs Sparsit, ever a kind of spy and dragon, is growing in closeness and noxious proximity to the Bounderbys. She relishes the growing (potentially scandalous) closeness of James and Louisa. (Later, she pictures Louisa as on a descending staircase which will lead to an abyss of misfortune.) But Louisa is called away to attend on her dying mother. While back at Stone Lodge, Louisa sees the influence that Sissy has had on the youngest sister, and on her mother, who feels that something has been “forgotten” by her husband, Mr Gradgrind—though she can’t pin it down. Mrs Gradgrind dies.

Mrs Sparsit spies on Louisa and Harthouse having an intimate conversation at the Bounderbys’ country home, and overhears the latter professing his love. Louisa agrees to meet him later. Mrs Sparsit, all anticipation of Louisa’s immanent downfall, follows Louisa but loses sight of her.

Louisa has, rather than meeting Harthouse, returned to Stone Lodge, where she both confronts and pleads with her father for help. Seeing Louisa’s regret at the hard, fact-laden childhood that has crushed all of her more sensitive feelings and hopes, Gradgrind begins to doubt and regret his own philosophy, and welcomes his heartbroken daughter as she collapses in her distress.

Discussion Wrap-Up (Weeks 3 & 4)

Miscellany, Whimsy, & What We Loved

Gina is with Chris & Rob, in considering Hard Times in her very top favorites:

Dickens, Milton, & the Brontës: Women & the Marriage Laws

Deborah considers “how much of a Miltonist Dickens was” as to Stephen’s views on marriage, and his grappling with versus societal norms and law:

I respond, wondering whether there is a Brontë connection here?

Rob comments on the influence–or possible influence–of each author upon the other, whatever Dickens may have claimed about not reading Jane Eyre:

The Women in Dickens: Mrs Sparsit & Louisa; Doubling

The Stationmaster compares Louisa with other similar Dickensian characters (Edith Dombey, Estella), and what makes her different–and, perhaps, tantalizingly challenging to Harthouse:

Chris considers Louisa’s “better angel” as it appears on the deathbed of her mother, and of her mother as “one of the finest examples of the result of gaslighting in literature”:

Is there doubling going on with Harthouse and Sparsit, in their mutual attempts to undermine the Bounderby marriage? The Stationmaster comments:

Chris responds:

Gaslighting Mrs Gradgrind

Was Mrs Gradgrind a kind of unlikely “prophetess on her deathbed”? The Stationmaster comments:

Above, Chris proposed Mrs Gradgrind as a prime example of being a victim of gaslighting. When the Stationmaster asked her to expand on this, Chris responds with a powerful reflection:

Cads & Villains: Tom and Harthouse

The Stationmaster comments on Tom as “an ordinary run of the mill jerk,” without the “flair” of a Gowan or Steerforth:

Chris comments on the use of the word “whelp” about Tom, and considers Harthouse as “a version of Richard Carstone”:

Dickens & the Strike; Stephen’s Promise to Rachael

The Stationmaster comments on the “nuanced” scene regarding the Union meeting:

Chris tries to get at the narrative function of the scene, and what Dickens seems to be telling us about the Masters and the Men.

And, as Chris asked above, what exactly was the promise that Stephen made to Rachael?

The Stationmaster and I respond:

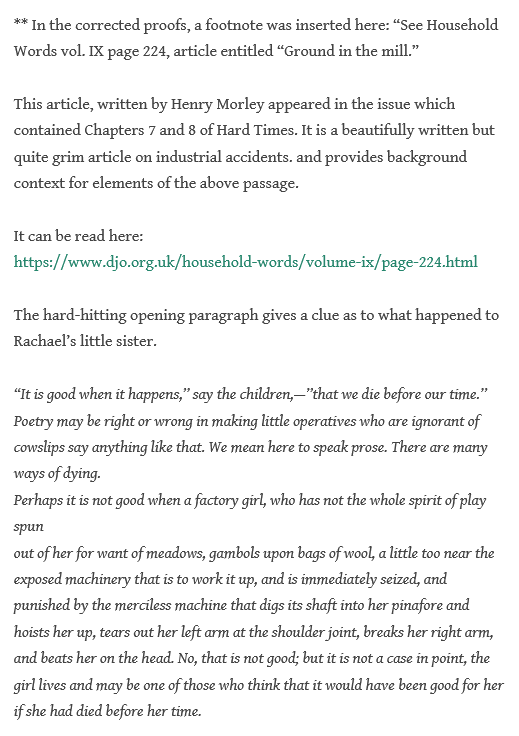

Thankfully, Rob seems to have come closest to finding the answer, which had been edited out from the published copy:

…and a Summary of Hard Times:

A Look-Ahead to Weeks 5 & 6 of Hard Times (26 Sept to 9 Oct, 2023)

This week and next, we’ll be finishing Hard Times with the shortest of the three “Books”–Book III, “Garnering,” Chapters 1-9–which was originally published in weekly parts in Household Words between 22 July and 12 August, 1854. Feel free to comment below for your thoughts this week and next, or use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter.

If you’d like to read it online, you can find it at a number of sites such The Circumlocution Office; you can download it from sites such as Gutenberg.

I’m going to write a longer, more critical comment later. In the meantime, here are some fun little items.

It’s quite telling that the political opponents, Bounderby and Slackbridge, end up joining forces to bash Stephen Blackpool.

I love the irony of Gradgrind, of all characters, being reprimanded “for (his) wicked imaginings” in Chapter 5.

Don’t read this paragraph if you haven’t finished the book yet. Does anyone else get the impression that Bounderby had started to believe his own propaganda about his mother and childhood? He doesn’t just talk about it at strategic moments when he’s trying to keep the Hands in line or when he wants to impress someone. He seems to enjoy bringing it up as often as possible. It’d be hard for him to forget the truth though while sending his mother thirty pounds each year.

LikeLiked by 2 people

If your starting point is that Bounderby is a self-obsessed narcissist, it absolutely makes sense that he starts to believe his own propaganda. His lies become an intrinsic component of who he is – and how he wants the world to see him.

LikeLiked by 4 people

I agree with you both about Bounderby–it seems like classic narcissistic behavior? Those who can say one thing when it serves them, and the opposite when it doesn’t; who seem to have conviction in their own narrative (i.e. lies). There appears to be some moment of shame when he’s confronted with his mother head-on, in conjunction with the very different stories he told of her, but it’s hard to tell how deep the shame is, or its origin. Is it just that he’s been called out and made to look like a liar? Or does he really feel any remorse at speaking untruthfully and unkindly of her? It definitely doesn’t seem to be the latter, so I’d be curious to know whether he still clings to his own narrative even then–though clearly he’s made distinctly uncomfortable by it all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As to Bounderby/Slackbridge, I’m wondering if it’s not so much a “teaming up,” as more of a scapegoating, each on their own side? Stephen is the one person who has the conviction(?) not to join the unionists, but still defends them to the management. I’m personally not sure what to make of his position, except that he kind of represents the “muddle” of it all, though I have trouble seeing a solution in his approach, except to advocate for a better understanding of each to the other (management, hands). I think he’s the scapegoat of the union side because he won’t join; he’s a scapegoat for Bounderby because SB still speaks up for his fellow Hands, but is less threatening, because he won’t join them. It’s a bit of a d—d if you do, d—d if you don’t scenario, and perhaps Stephen represents the kind of everyman who suffers for the injustices of both sides.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Maybe I shouldn’t have used the phrase “joining forces.” Obviously, the two aren’t deliberately and knowingly teaming up. But the fact that both of them publicly bash Stephen Blackpool and give him no benefit of the doubt shows that there’s not a big difference between them morally.

I kind of hope Bounderby’s mother never found out what her son had been saying about her.

Re: your comment below. Now I want to read a fanfic about the gentleman in small clothes from Nicholas Nickleby and his long-lost nephews and nieces. LOL.

LikeLiked by 2 people

LOL! I’d read that too! Probably, I’d even *write* it! 😂 (Do you know, I’ve been practicing polymer clay doll sculpting in my non-existent spare time😂–hence, it is put aside for now–but the one I was working on when I had to leave off was that mad gent!)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wrote before about how some people dislike politically driven books, movie, plays, etc. that are largely about the creators ranting about how stupid and evil their ideological opponents are. I have an inconsistent stance on the subject. Sometimes I find those annoying and sometimes I don’t. (For the record, it’s not based on whether or not I agree with them. Not entirely anyway.) Most of Dickens’s books fit the description but I don’t have a problem with their bitterness and soapbox-iness…except for with Hard Times. (Just a bit.)

So much of the final third of the book is about Gradgrind’s philosophy being flung in his face and coming back to bite him that it starts to feel tiresome. I kind of want to yell at Dickens, “OK! We get the point! Even the character gets the point by now. He got it several chapters ago. You can stop tormenting him! And I also understand the point you’re making about society. You don’t have to explain it again.” Bounderby getting his words flung back at him is more fun. But even with him, I can’t quite enjoy his secrets being revealed to everyone as much as I enjoy Mr. Bumble’s comeuppance or that of Wackford Squeers. You could argue though that we’re not supposed to enjoy it since, amusing as it is, it’s also really sad for his poor, mistreated mother.

There’s far less of a focus in Hard Times on positive characters than there is in other books by Dickens. I know there are critics and readers out there who find his heroic and innocent characters boring and even annoying, but I find that without that innocent goodness to balance it out, the nastiness of the other characters, interesting and entertaining though they are, can be kind of overwhelming in its unpleasantness. And I also find the positive characters that we do get in Hard Times to be not the most effective in Dickens. I’m kind of cynical about the parts relating to Stephen Blackpool’s marriage, knowing that Dickens parted ways with his wife and pretty much every biographer blames him, not her though, of course, you can say the social message he’s delivering still stands. (I actually don’t care much about the real lives of authors when I read their books BTW. The fact that I think about Dickens’s biography at all when I read Hard Times shows that it’s not entirely working for me.) Also, Stephen’s dialect is a pain to read. (John Browdie’s in Nicholas Nickleby can be hard too but John Browdie is fun.) Sleary’s speech impediment is also something of a chore though I respect the argument Chris has made in its favor.

My favorite of the positive characters is Sissy. (Well, she and Rachael.) But I really wish she were developed more. It’s odd how after being nearly absent from the book’s middle third, she becomes the most actively heroic figure in the final act, the one who takes care of Louisa, sends Harthouse packing (that’s an awesome scene), helps find Stephen and enables Tom’s escape. It’s hard to understand how she could have kept her goodness growing up in the Gradgrind household. Since she wanted to please Mr. Gradgrind, unlike Tom and Louisa who resented him to varying degrees, wouldn’t she be more likely to become brainwashed? And how did she have such a good impact on Jane? It’s hard to imagine her introducing anything into the nursery of which Gradgrind would have disapproved. I really wish this could have been explored more. Then again, maybe if it had, it would have come across as even less convincing to me.

Anyway, I think all of that is why Hard Times is one Dickens book that I’d describe as bitter in a bad way (as opposed to, say, Oliver Twist which is bitter in a fun, invigorating way.) And why, for all the things I love about it, it leaves a slightly unpleasant aftertaste in my mouth. But, hey, I still consider it a great book in its way.

P.S.

Did Dickens still have Chancery on his mind when he wrote this? “Had (Bounderby) any prescience of the day, five years to come, when Josiah Bounderby of Coketown was to die of a fit in the Coketown street, and this same precious will was to begin its long career of quibble, plunder, false pretences, vile example, little service and much law?”

LikeLiked by 2 people

Haha, that scene where Sissy “sends Harthouse packing” is my favorite scene in the book! I whooped aloud.

LikeLiked by 4 people

One of the many reasons why our Dickens Club is so marvelous is that, besides a deepening appreciation of the trajectory of Dickens’s works as a whole, there is more appreciation of the individual works, as we discuss them. For many of us (at least, Gina, Rob, Chris, and maybe Deborah S. and Daniel?) HT is among their Dickensian favorites, so it has really helped me to deepen my own appreciation–as did Rob’s reading of it!

As much as I love what Dickens is often saying here (especially about the Imagination; about Fact & Fancy), and as much as I LOVE the Coketown factory atmosphere, I admit that I do have a “hard time” with Hard Times. Historically, it has always been my least favorite Dickens, along with Oliver Twist. (Barnaby was fairly low on the list too, mostly because I didn’t remember by reading from years ago very well at all–until our readalong of it, which bumped it way up!) And I think the Stationmaster here hits several of the reasons, notably: 1.) Stephen; 2.) the “bitter” tone.

There is perhaps a similarity in tone to Oliver Twist; a darker or more bitter tone. At least with Oliver, I do feel for Oliver more, enjoy Bumble more, etc. But for all of HT’s tight editing and succinctness, I feel that time passes much more quickly in reading his more rambling works, where some of its incidental or side-plot characters and scenes somehow make it all the more vibrant, just because these characters *had* to exist, whether or not they greatly forward the plot; it is the sheer joy of making sure one is exposed to some of the most vibrant characters you’ll ever meet. Why the mad gent in smallclothes in Nicholas Nickleby? He doesn’t turn out to be anyone’s rich uncle who dies…but the world would be a sadder place without “Mr Cucumber”. 🙂 Here, the characters seem constrained to fit into a more allegorical piece; perhaps, a parable. (The same argument/complaint might be raised against my favorite novel, A Tale of Two Cities…but why does that one *work* so beautifully for me, and this one not so much? In ATTC too, we could say that Stryver is our Bounderby; Jerry Cruncher is the kind of “comic” character who isn’t as funny as many “comic” characters in Dickens; there is a darker tone overall; it is arguably a parable or fairy story that just happens to be set during the French Revolution. But…Sydney! More on that next year, eh?)

Gradgrind is an interesting character and Sissy is wonderful. (Agreed that her scene with Harthouse is the best!) But aside from them, I don’t feel terribly invested in anyone, and I still find Stephen problematic. I try and try to like him better, to feel for him more. God knows, he’s put through the mangle! But why doesn’t he *work* for me? Perhaps it is something in the way he is written–a bit “victimy”. Perhaps the same is somewhat true of Louisa. Both characters can so well put words to why they’re in such a bad situation, that it feels a bit “woe is me” after a while…I know that’s not fair, but I’m trying to understand why they don’t move me as other oppressed or haunted or victimized characters in Dickens do.

I’d love to hear everyone’s thoughts on this, in order to continue deepening the appreciation of HT. Already, between the wonderful comments, Chris’s personal narrative about encountering Hard Times just at that **right time** (one of my favorite posts!), and Rob’s wonderful reading, I have been enjoying it much more than I anticipated. But I confess I’m still stuck on Stephen, for one, and wondering why exactly that is.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Rach – I’m going to run with your comment “Here the characters seem constrained to fit into a more allegorical piece; perhaps, a parable”. I’m wondering if constraint isn’t the plan seeing as how EVERYTHING seems constrained.

The physical work is constrained, from the word count, to the chapter titles (the longest is 5 words), to the theme, to number of characters, to the quick frequency of installments – weekly rather than monthly.

The creative work is constrained from the M’Choakumchild’s school (choke = being check), to what is taught and how it is taught, to the town with its uniformity, to the monotony of the machines in the factories, to the repetitive work being done by the Hands who all seem the same. Even at the Circus, though it seems free and loose, constraint seeps in – in its being relegated to the outskirts of town, in that “the male part of the company . . . all assumed the professional attitude when they found themselves near Sleary”, and in E.W.B. Childers’s checking of Mr Kidderminster’s sarcasm – “Kidderminster, stow that!” (Bk 1 Ch 6)

I’m wondering if the constraint of the characters – in their conception, their roles and in how they perform their roles – isn’t part of the overall plan to express the notion that Facts constrain whereas Fancy allows expansion via the freedom to wonder.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I like that, Chris. One might fancy (so to speak) Dickens writing it just for his detractors–like, “You want less Fancy & more Fact/’Realism’? Here you go! This is where it all leads us.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m so glad my reading could help, Rach. I’ve spent a lot of time in the north of England so I suppose it was a little easier for me to ‘translate’ Stephen into spoken form! Sleary was a real challenge too

LikeLike

I too am a fan of the “Very Ridiculous” chapter in which Sissy takes Mr Harthouse to task and dismisses him. (Bk 3 Ch 2)

Sissy, like the Circus from which she comes, is the symbol of emotional intelligence. She knows by instinct what all the Facts miss – she understands the “one thing needful”. She repays Mr Gradgrind for taking her in not by becoming a scholar of Fact as he had hoped, but through her silent and gentle influence over his household. I don’t find it strange that Sissy should be able to retain her goodness during her years under the Gradgrind regime.

As we saw with Oliver, Smike, Dick Swiveller, Barnaby, Tom Pinch, Miss Tox, Tommy Traddles, and Esther Summers, Dickens’s innately “good” characters will always remain “good” no matter what is thrown at them, where they find themselves, or by what they are surrounded.

The lessons Sissy learned in her formative years from her father and the Circus, infused with the love with which they were taught, are her “key-note” (to use Dickens’s term). The M’Choakumchild/Gradgrind facts and Mrs Gradgrind’s neediness cannot override this key-note because of the strength of Sissy’s belief, hope, and faith in her father:

“It is lamentable to think of; but this restraint was the result of no arithmetical process, was self-imposed in defiance of all calculation, and went dead against any table of probabilities that any Actuary would have drawn up from the premises. The girl believed that her father had not deserted her; she lived in the hope that he would come back, and in the faith that he would be made the happier by her remaining where she was.” (Bk 1 Ch 9)

Sissy’s restraint (constraint) sustains her, allows her to live. Were she to compromise this restraint even a little, just as if she were to give up the bottle of nine oils, she would surely break her heart and become another M’Choakunchild automaton. Her presence in the Gradgrind household, as we have seen, illuminates the way for its rehabilitation. Because Sissy is allowed to “live[ ] with the rest of the family on equal terms” (Bk 2 Ch 9), her ways and manners, which are no doubt less stiff, less formal, less factual than theirs, would soon become familiar to them and influence their own manners. Mrs Gradgrind takes to musing about what “ology” has been missed, Jane’s face is “beaming”, and the “forlorn” Mr Gradgrind says to his equally forlorn daughter, “Louisa, I have a misgiving that some change may have been slowly working about me in this house, by mere love and gratitude; that what the Head had left undone and could not do, the Heart may have been doing silently.” (Bk 3 Ch 1) Sissy knows, innately, the real “one thing needful” – love.

Sissy’s interview with Mr Harthouse is the first overt example of this knowledge. Sissy goes to him not because she has been told to but because she knows he must be sent away and that she is the only person who can ensure his removal. Had Mr Gradgrind as Louisa’s father, or Mr Bounderby as Louisa’s husband, or even Tom as Louisa’s brother tried to reason with Mr Harthouse they would have met with disdain, derision and dismissal. Sissy as Louisa’s champion and “ambassadress” has no personal agenda other than her love for Louisa and thus can put herself entirely aside in pursuit of her objective. Thus, her “child-like ingenuousness . . . her modest fearlessness, her truthfulness which put all artifice aside, her entire forgetfulness of herself in her earnest quiet holding to the object with which she had come; all this, together with her reliance on [Harthouse’s] easily given promise—which in itself shamed him—presented something in which he was so inexperienced, and against which he knew any of his usual weapons would fall so powerless; that not a word could he rally to his relief”. (Bk 3 ch 2)

Beyond effecting Harthouse’s removal Sissy has also managed to effect some emotional growth in him – he feels ashamed of himself. “A secret sense of having failed and been ridiculous—a dread of what other fellows who went in for similar sorts of things, would say at his expense if they knew it—so oppressed him, that what was about the very best passage in his life was the one of all others he would not have owned to on any account, and the only one that made him ashamed of himself.” (Bk 3, Ch 3) Even if this “best passage of his life” is known only to himself and Sissy, the fact that he feels ashamed at having “been ridiculous” is, hopefully, character building enough to make him more careful of himself and others in the future. Who else by Sissy could have made this so?

The second overt example of Sissy’s knowledge is her arrangements for Tom’s escape – but that’s another post.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I’d like to comment on the 1977 miniseries and 1994 movie adaptations of Hard Times. Each has its pros and cons. The 1977 series definitely has better visuals. Sets, costumes and makeup all look much more real than the ones from the 1994 movie. (Though there are some design elements from the 1994 Hard Times that I like, mainly the deliberate overuse of bright red inside Bounderby’s house.) You really get a sense of how miserable it is for the poor of Coketown just by looking at them. There’s also some good visual storytelling, like a scene of Tom watching and presumably betting on a cockfight. You get a much better sense of Coketown as a community here than in the 1994 movie, which had hardly any extras. And I love the final image which wordlessly foreshadows Louisa’s fate as described in Dickens’s epilogue. (“…all children loving her; she, grown learned in childish lore; thinking no innocent and pretty fancy ever to be despised…”)

However, I much prefer the cast of the 1994 movie. Not that the acting in the 1977 miniseries is bad: it’s generally fine. I just found the cast in 1994 more enjoyable. In particular, I found Dilys Laye’s Mrs. Sparsit to be much more fun than Rosalie Crutchley’s. I admit that I’ve sometimes wondered if Emma Lewis’s Sissy from 1994 was a little too smiley considering all the sadness going on around her but I’ve decided that’s better than Michelle Dibnah’s miserable looking Sissy from 1977. I’d like to give a special shoutout to Harriet Walker’s Rachael from 1994. I don’t know much is due to the actress and how much to the makeup, but she really looks like a woman who’s had a hard life, not like some Hollywood starlet. I’m used to seeing her play snobby, negative characters in period pieces like this, so this is a nice change.

Also, despite having more time to tell the story, 1977 Hard Times actually cuts more from the book’s story than the 1994 one. The revelations about Bounderby’s mother are dropped and so is Bitzer’s role in the climax. I know I implicitly criticized the last part with Bitzer in the book for being overly vindictive and “rant-y,” but it still made for a more exciting climax than the one in the miniseries. And they weirdly spend a lot of time with Bitzer earlier in the adaptation even though he no longer plays much of a role in the plot. The 1977 series may be longer and slower paced than the 1994 movie, but it really doesn’t make the best use of its runtime. To be honest, while I admire aspects of it, I find the whole thing to be a bit of a slog, lacking that Dickensian energy and humor. (Though there’s at least one good humorous line original to this version. Kidderminster introduces Gradgrind and Bounderby to Sleary as “a new clown and a new dog.”) I also think the dialogue in the 1994 movie might be relatively closer to that in the book, though the 1977’s script has its moments.

The writer and director for the 1994 Hard Times, BTW, was playwright Peter Barnes who also wrote the high quality 1999 Christmas Carol movie. He also wrote one of my favorite adaptations of Lewis Carroll’s Alice books and the dazzling 2000 Arabian Nights miniseries.

This reading group has inspired me to do something I’ve been planning on doing for a while: write a screenplay based on Hard Times. I just did it for fun. I’m not intending to try to get it greenlit or anything. It’s interesting though to speculate about whom they would cast if it was greenlit. Louisa would be such a juicy part for an actress to play. I read somewhere that when Emma Thompson was adapting the classic book, Sense and Sensibility, into a movie script, someone advised her to adapt the whole thing and when she got to anything that wasn’t working, change it or cut it. That’s what I tried to do with Hard Times. Even though it’s not my favorite Dickens book, the fact that it was the shortest meant I felt I would have to cut the least to make it a movie. There still ended up being some painful sacrifices though, mainly the friendship between Sissy and Rachael which I felt I didn’t have time to develop. (It’s ironic that I’ve criticized the book for not focusing more on the pleasanter character since there’s arguably even less of them in my script, at least of Stephen and Rachael.) If anyone would like to read what my screenplay, I can email a PDF to Rach, and she can email it to you. Just ask.

The thing about both the 1977 miniseries and the 1994 movie is that for all their virtues, neither of them is going to appeal to a viewer who isn’t already a fan of the book. I’d like for there to be an adaptation that draws in newcomers and non-Dickens aficionados like the 2005 Bleak House did. I don’t know if my version could do that if it were actually made into a movie. (I think I actually stuck closer to the book’s dialogue than either Peter Barnes or Arthur Hopcraft, who wrote the 1977 version, did.) But someone should try to do it. The story is certainly interesting enough to appeal to mainstream audiences if presented in the right way. The suspenseful middle part with Harthouse trying to seduce Louisa would make for a great psychological thriller.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I watched the 1994 version and really didn’t like it. I thought it was poorly cast, especially Mrs Sparsit. It also seemed rushed, like they really didn’t want to take the time to perform it properly but just wanted to get it filmed. I found myself skipping ahead. I’ll try to find the 1977 version.

And I agree, there needs to be a new, updated version – why not submit your screenplay? You never know . . . !

LikeLiked by 1 person

Chris,

the 1977 version is all on YouTube 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

The question came up in one of my in-between readings about Tom’s escape – is it right for Tom to escape?

In a strictly legal sense, of course, it is not. Tom is guilty of the crime, he admits it, and every one involved in his escape – Sissy, Mr Gradgrind, Louisa, pretty much the entire Circus – is guilty of aiding and abetting a felon. Legally, Tom should be apprehended, arrested, and prosecuted, as should those who help him. Granted, Tom is shipped out of the country – transported, if you will – which would be a likely outcome had he been convicted in a court of law. So in a way he really doesn’t escape punishment, he just doesn’t get prosecuted. (And one wonders why Bounderby and his new right hand man, Bitzer, don’t go after Gradgrind, Sleary, et al., for their part in the escape, but apparently the calculus of doing so does not square with their self-interest.) So, no, it is not right, legally, that Tom escapes.

In tandem with the legal aspect of the question is the moral (ethical) aspect – Is it morally right for Tom to get away? Clearly we’re meant to sympathize with Mr Gradgrind in light the complete collapse of his philosophy of Fact. But this does not morally justify Tom’s escape. We’re also meant to understand Sleary’s repaying a debt – Gradgrind stood by Sissy, now Sleary will stand by Grandgrind. But this doesn’t morally justify Tom’s escape either.

And I question whether facilitating Tom’s escape is an equal exchange for Gradgrind’s adoption, if you will, of Sissy. Sissy would have been just fine if left at the Circus, perhaps better emotionally than she was with the Gradgrinds; it is the Gradgrinds’ who benefit from taking Sissy in. Tom is neither better nor worse off for his escape. He has his liberty, but the price is steep. He remains a felon, cannot return home, is sent away with no friends or prospects, and dies alone, “in penitence and love for” Louisa. (Bk 2 Ch 9) But this phrase is ambiguous because it does not say specifically that he is sorry for having committed the robbery and setting Stephen as patsy. The phrase could mean he simply regrets having “repulsed” Louisa at their parting. I get less of a sense that Tom feels remorse for his criminal deeds than I do that selfish Tom is selfish still and his regret is all self-interest. Would it have been better for him to have been prosecuted and given a sentence of some years after which he could return to his family? Would incarceration have rehabilitated him or further hardened him? Either way, his family bears the burden of his crime – is it better to have a fugitive relative or a convicted relative?

Morally the right thing is pretty straight forward – Tom should admit his crime, face the legal consequences, and atone for his misdeeds, which oddly sounds a lot like Utilitarianism.

So why is Tom allowed to escape? Why does Dickens plot his story such that legal right and moral right are subverted in favor of an unlikeable Whelp? Was it RIGHT for Dickens – the friend of the people, the man who wished to teach, among other things, morality and Christian behavior through his writing – to let Tom escape?

I think it was, and I think Dickens does so not to condone such behavior but to show yet again the grey area between right and wrong, between Fact and Fancy, between Order and a muddle. No, it’s not right that Tom escapes, especially because Stephen the innocent pays the ultimate price for Tom’s criminal, immoral act, but he does because he has “friends” who have the wherewithal to facilitate his escape. This is another instance – like the divorce situation – of different rules for the rich than for the poor, for the privileged than for the disempowered. The societal imbalance promoted by ill-considered policies like Utilitarianism creates divisions and animosities that ultimately destroy the very cohesion they seek to create. They do so because they are infused with, motivated by self-interest rather than love. Paraphrasing Mr Sleary, if love guides our actions we’ll usually do the right thing because love “hath a way of ith own of calculating or not calculating, whith thomehow or another ith at leatht ath hard to give a name to, ath the wayth of the dogth ith!” (Bk 3, Ch 8)

LikeLiked by 1 person

The question has occurred to me too of why Bitzer doesn’t take legal action against the heroes. Is there not enough evidence with just his word against all of theirs? That’s the best I can come up with.

LikeLike

Another reason occurred to me why Hard Times strikes me as more unpleasant than other, similarly dark Dickens books. In it, Dickens is much clearer about what’s he against than what he’s for. He’s deeply cynical about big business owners like Bounderby but he’s also really skeptical about Unions (though not necessarily about Union members.) The novel’s most articulate social critic is Stephen Blackpool and even he says he doesn’t know how to fix the problems of Coketown. He just knows what won’t help them. I don’t really want to criticize Dickens or Stephen for this since I, myself, don’t see any obvious solutions for many social problems in life and there’s no reason that can’t be expressed through art. But it means that the hope offered by Hard Times, no Dickens book being completely hopeless, is rather vague and hard to grasp.

Dickens is a little more specific in what he’s advocating in the education plotline than in the poverty plotline (though I’d argue the first is supposed to be an allegory of sorts for the second.) But even there, the goodness of Sissy and Sleary isn’t explored with the same depth as the dysfunction of the Gradgrind family and can come across as just a vague niceness. The most concrete and specific act of charity in the book is Louisa giving money to Stephen (actually, it might be her mere act of listening to him with respect) and that leads to one of the most concrete and specific acts of evil in the book, Tom taking advantage of Stephen and framing him,

I feel bad that so many of my comments this last week are describing the book negatively. I really do think it’s great in its way.

P. S.

I’ve never actually seen the movie, Titanic, but I know from cultural osmosis that it features a scene where the male romantic lead dies while the female romantic lead grasps his hand. Could that have been inspired by Stephen and Rachael? Probably not but I like to think so. LOL

LikeLiked by 1 person

Some absolutely great comments for this final section. This club is fab! 🙂

I was hoping to get some of my own thoughts down, but alas, I have had a rather busy week and am running out of time to organise my many thoughts about this wonderful novel.

So I am going to cheat and share a few perspectives from a variety of sources, largely without comment

But I do not hold that Hard Times is any more political than Dickens’ other works. Utilitarianism and Industrialisation etc are just features of what is as usual for Dickens a story of Human interest. And I love Ackroyd’s assessment that Hard Times is a fairy tale for the industrial age. It is an extended treatment of the kind written about in the Christmas Books. In place of any supernatural agent effecting a change for good in the characters, Hard Times gives us Sissy Jupe 🙂

and now, those quotes and passages:

John Ruskin

The essential value and truth of Dickens‘s writings have been unwisely lost sight of by many thoughtful persons, merely because he presents his truth with some colour of caricature. Unwisely, because Dickens’ caricature, though often gross, is never mistaken. Allowing for his manner of telling them, the things he tells us are always true. I wish that he could think it right to limit his brilliant exaggeration to works written only for public amusement; and when he takes up a subject of high national importance, such as that which he handled in Hard Times, that he would use severer and more accurate analysis. The usefulness of that work (to my mind, in several respects the greatest he has written) is with many persons seriously diminished because Mr. Bounderby is a dramatic monster, instead of a characteristic example of a worldly master; and Stephen Blackpool a dramatic perfection, instead of a characteristic example of an honest workman. But let us not lose the use of Dickens‘s wit and insight, because he chooses to speak in a circle of stage fire. He is entirely right in his main drift and purpose in every book he has written; and all of them, but especially Hard Times, should be studied with close and earnest care by persons interested in social questions.

They will find much that is partial, and, because partial, apparently unjust; but if they examine all the evidence on the other side, which Dickens seems to overlook, it will appear, after all their trouble, that his view was the finally right one, grossly and sharply told.

G.K. Chesterton

Dickens was there to remind people that England had rubbed out two words of the revolutionary motto, had left only Liberty and destroyed Equality and Fraternity. In this book, Hard Times, he specially champions equality. In all his books he champions fraternity.

It may be bitter, but it was a protest against bitterness. It may be dark, but it is the darkness of the subject and not of the author. He is by his own account dealing with hard times, but not with a hard eternity, not with a hard philosophy of the universe. Nevertheless, this is the one place in his work where he does not make us remember human happiness by example as well as by precept. This is, as I have said, not the saddest, but certainly the harshest of his stories. It is perhaps the only place where Dickens, in defending happiness, for a moment forgets to be happy.

Claire Tomalin – Charles Dickens: A Life

The chief message of the book concerns the bad effects of an education that confines itself to purely factual and practical matters learnt by rote, ignoring the importance of imagination, sensibility, humour, games, poetry, entertainment and fun.

Peter Ackroyd

But Dickens was not interested in writing a political or social tract; he was writing a fairy story of the industrial age.

The New Yorker – Feb 2022 – Louis Menand

Dickens was a social critic. Almost all his fiction satirizes the institutions and social types produced by that dramatic transformation of the means of production. But he was not a revolutionary. His heroes are not even reformers. They are ordinary people who have made a simple commitment to decency. George Orwell, who had probably aspired to recruit Dickens to the socialist cause, reluctantly concluded that Dickens was not interested in political reform, only in moral improvement: “Useless to change institutions without a change of heart—that, essentially, is what he is always saying.”

source article (worth a read) https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/03/07/the-crisis-that-nearly-cost-charles-dickens-his-career-robert-douglas-fairhursts-the-turning-point

Charles Dickens – ‘On Strike’ – Household Words February 1854

ON STRIKE.

Travelling down to Preston a week from this date, I chanced to sit opposite to a very acute, very determined, very emphatic personage, with a stout railway rug so drawn over his chest that he looked as if he were sitting up in bed with his great coat, hat, and gloves on, severely contemplating your humble servant from behind a large blue and grey checked counterpane. In calling him emphatic, I do not mean that he was warm; he was coldly and bitingly emphatic as a frosty wind is.

“You are going through to Preston, sir?” says he, as soon as we were clear of the Primrose Hill tunnel.

The receipt of this question was like the receipt of a jerk of the nose; he was so short and sharp.

“Yes.”

“This Preston strike is a nice piece of business!” said the gentleman. “A pretty piece of business!”

“It is very much to be deplored,” said I, “on all accounts.”

“They want to be ground. That’s what they want to bring ’em to their senses,” said the gentleman; whom I had already began to call in my own mind Mr. Snapper, and whom I may as well call by that name here as by any other. *

I deferentially enquired, who wanted to be ground?

“The hands,” said Mr. Snapper. ” The hands on strike, and the hands who help ’em.”

I remarked that if that was all they wanted, they must be a very unreasonable people, for surely they had had a little grinding, one way and another, already. Mr. Snapper eyed me with sternness, and after opening and shutting his leathern-gloved hands several times outside his counterpane, asked me abruptly, ” Was I a delegate?”

I set Mr. Snapper right on that point, and told him I was no delegate.

“I am glad to hear it,” said Mr. Snapper.

“But a friend to the Strike, I believe?”

“Not at all,” said I.

“A friend to the Lock-out?” pursued Mr. Snapper.

“Not in the least,” said I.

Mr. Snapper’s rising opinion of me fell again, and he gave me to understand that a man must either be a friend to the Masters or a friend to the Hands.

“He may be a friend to both,” said I.

Mr. Snapper didn’t see that; there was no medium in the Political Economy of the subject. I retorted on Mr. Snapper, that Political Economy was a great and useful science in its own way and its own place; but that I did not transplant my definition of it from the Common Prayer Book, and make it a great king above all gods. Mr. Snapper tucked himself up as if to keep me off, folded his arms on the top of his counterpane, leaned back and looked out of the window.

“Pray what would you have, sir,” enquired Mr. Snapper, suddenly withdrawing his eyes from the prospect to me, “in the relations between Capital and Labour, but Political Economy?”

I always avoid the stereotyped terms in these discussions as much as I can, for I have observed, in my little way, that they often supply the place of sense and moderation. I therefore took my gentleman up with the words employers and employed, in preference to Capital and Labour.”

“I believe,” said I, “that into the relations between employers and employed, as into all the relations of this life, there must enter something of feeling and sentiment; something of mutual explanation, forbearance, and consideration; something which is not to be found in Mr. M’CulIoch’s dictionary, and is not exactly stateable in figures; otherwise those relations are wrong and rotten at the core and will never bear sound fruit.”

Mr. Snapper laughed at me. As I thought I had just as good reason to laugh at Mr. Snapper, I did so, and we were both contented.

Full article can be found here

https://www.djo.org.uk/household-words/volume-viii/page-553.html

LikeLike

I theoretically agree that Hard Times isn’t any grimmer or more political (in a bad way) than any other Dickens book. (Well, maybe more than The Pickwick Papers.) But all I can speak for is my experience reading it and whenever I do, I feel like it doesn’t transcend its political purpose quite as well as the author’s other books, though I can really only speculate as to why.

Interesting idea that Sissy is less like the heroine of the book than the mentor figure (like the ghosts, goblins and fairies of Dickens’s novellas.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I would say that The Chimes delves into much darker terrain than Hard Times, yet in the former they are presented as a dream or vision and perhaps in some way lose a bit of the sting. There is quite an affinity between these two works. Trotty’s convictions that the poor are undeserving of happiness are modified by his vision. In the same way that the quiet influence of the emotionally intelligent and competent Sissy is a large part of leading Gradgrind to his better understanding of the balance between the head and the heart.

Gradgrind is redeemed throughout Hard Times, like Scrooge, Trotty, Tackleton, (Dr. Jeddler) and Redlaw – there are agents working their influence for good: the three spirits, the spirits of the bells, Dot and the Cricket, (Battle of Life is harder to see, but the sacrifice Marion makes for her sister is not far off Sissy’s care for Louisa in tackling Harthouse) and Milly Swidger (very much like Sissy I would say)

But if you think about what Sissy does throughout Hard Times when considering the ending of The Chimes (itself expressing the same final appeal as Hard Times) my theory kind of works 🙂

‘…and in your sphere—none is too wide, and none too limited for such an end—endeavour to correct, improve, and soften them. So may the New Year be a happy one to you, happy to many more whose happiness depends on you! So may each year be happier than the last, and not the meanest of our brethren or sisterhood debarred their rightful share, in what our Great Creator formed them to enjoy.’

or, in other words:

‘Dear reader! It rests with you and me, whether, in our two fields of action, similar things shall be or not. Let them be! We shall sit with lighter bosoms on the hearth, to see the ashes of our fires turn gray and cold.’

LikeLiked by 2 people

The charting of the relationship between Sissy and Louisa throughout the novel is a highlight for me… especially the looks between them. They are both fascinating characters and their story gives rise to one of the best sentences, for me, in the entire Dickens canon:

LikeLiked by 2 people

I found this very interesting article, “‘Hard Times’ and the Structure of Industrialism: The Novel as Factory”, by Patricia E. Johnson which posits that the novel is “much more coherent as a representation of industrialism than has been realized” (128) by virtue of its “uses [of] the physical structure of the factory itself as both the metaphor for the destructive forces at work on its characters’ lives and as the metaphor for its own aesthetic unity as a novel.” (129)

Johnson argues that “the setting and shape of the novel cohere strikingly” in that it “imitates the closed economy of the factory system” (129). Mirroring a physical factory, the novel has a “firm outer framework” (129) composed of “The first seven and last three chapters of the novel” (131). This framework “surrounds and contains an inner core of smoke and fire – represented by the stories of Stephen Blackpool . . . and Louisa Gradgrind”. (129)

This arrangement points to the idea – the fact? – that it is not on the outside of a factory where change happens – as it is not in the Gradgrind system or in Utilitarianism – but on the inside of the factory where innovations in production, procedures, or formulas become apparent and are incorporated into the “goods” that are being manufactured. If a business does not innovate or change with the times it will not survive. “Thus Dickens’s primary purpose goes beyond Fancy. He does not provide us with an escape from the system but instead holds us to a strict accounting of what it costs to maintain it.” (136)

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1PVY4qUany2QlQ3sJMqGknWy_jugdoOde/view?usp=sharing

LikeLike

I clicked on your link but it’s denying me access.

LikeLike

Sorry – try the link now, it should work. I had wrong setting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Got it! Thanks.

LikeLike