Wherein The Dickens Chronological Reading Club Wraps up our first 2 weeks (Weeks 95-96 of the #DickensClub) of Little Dorrit; including a summary and discussion wrap-up; with a look-ahead to Weeks 3 and 4.

(Banner Image: by James Mahoney. Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham for Victorian Web.)

by the members of the #DickensClub, edited/compiled by Rach

“In our course through life we shall meet the people who are coming to meet us, from many strange places and by many strange roads…and what it is set to us to do to them, and what it is set to them to do to us, will all be done.”

Friends, what a lively discussion we have had over these first two weeks with Little Dorrit! We’ve discussed its structure, its marvelous characters, its haunting atmosphere, and the “haunted” Dickens himself.

The conversation has been so rich that there was no way to include it in full, so I have tried to highlight a few points within the themes discussed. I hope you have a chance to read it in full under the introduction.

A few quick links:

- General Mems

- Little Dorrit, Book I, Chs 1-18 (Weeks 1 & 2): A Summary

- Discussion Wrap-Up (Weeks 1 & 2)

- A Look-Ahead to Weeks 3 & 4 of Little Dorrit (7-20 November, 2023)

General Mems

If you’re counting, today is Day 672 (and week 97) in our #DickensClub! This week and next, we’ll be continuing with weeks 3 and 4 (Book I, Chapters 19-36) of Little Dorrit, our twentieth read as a group. Please feel free to comment below this post for the third and fourth weeks’ chapters, or use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter.

No matter where you’re at in the reading process, a huge “thank you” for reading along with us. Heartfelt thanks to our dear Dickens Fellowship, The Dickens Society, and the Charles Dickens Letters Project for retweets, and to all those liking, sharing, and encouraging our Club, including Gina Dalfonzo, Dr. Christian Lehmann and Dr. Pete Orford. Huge “thank you” also to The Circumlocution Office (on twitter also!) for providing such a marvellous online resource for us.And for any more recent members or for those who might be interested in joining: the revised two-and-a-half year reading schedule can be found here. If you’ve been reading along with us but aren’t yet on the Member List, we would love to add you! Please feel free to message Rach here on the site, or on twitter.

And for any more recent members or for those who might be interested in joining: the revised two-and-a-half year reading schedule can be found here. Boze’s introduction to Little Dorrit can be found here, and Chris’s supplemental reading materials for this novel can be found here. If you’ve been reading along with us but aren’t yet on the Member List, we would love to add you! Please feel free to message Rach here on the site, or on twitter.

Little Dorrit, Book I, Chs 1-18 (Weeks 1 & 2): A Summary

(Images below are from the Charles Dickens Illustrated Gallery.)

“Thirty years ago, Marseilles lay burning in the sun, one day….”

On one broilingly hot day in August in Marseilles, we meet two prisoners: the one, Monsieur Rigaud, accused of murdering his wife; the other, a common smuggler, John Baptist Cavalletto, fearful of his cellmate. Rigaud is given the best food, insists he is a gentleman, and tells the story of his wife’s death, making it seem an accident.

We then meet up with a group of travelers just about to get out of quarantine as they return to England. Among the group is Arthur Clennam, returning after a 20-year absence in China where he helped to manage the family mercantile business. (We learn that, now about 40, Clennam, a child of a strict upbringing, sacrificed his youth for the family business.) Clennam’s father has just died abroad. During the travels, Arthur meets the Meagles family—Mr and Mrs Meagles, their slightly spoiled daughter, “Pet,” and Pet’s adopted companion, nicknamed “Tattycoram,” a young woman resentful of all of the fussing over Pet, who becomes afraid of another of the travelers: the mysterious Miss Wade, who rebuffs all of her travelling companions’ attempts to show friendliness to her; she speaks enigmatically of the future.

“In our course through life we shall meet the people who are coming to meet us, from many strange places and by many strange roads…and what it is set to us to do to them, and what it is set to them to do to us, will all be done.”

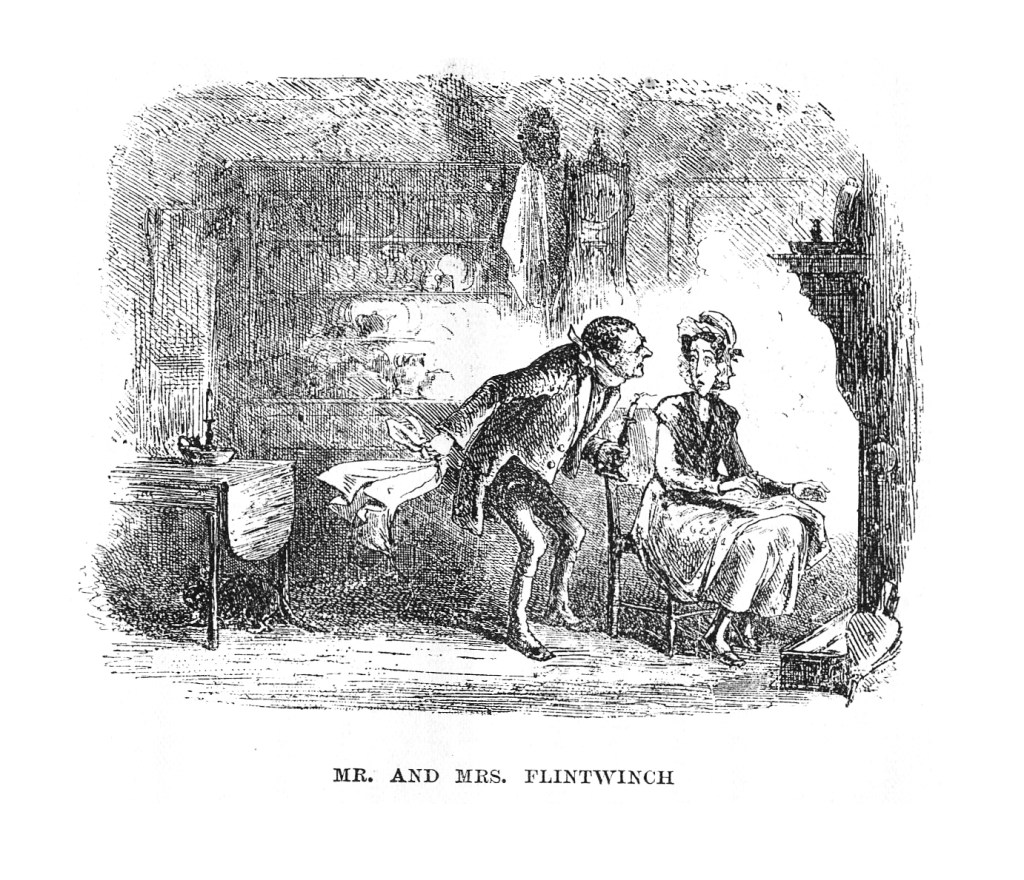

At his childhood home, Arthur Clennam faces a cold reception both from an invalid mother who has shut herself up in her house for years, and from her servant—almost, a business partner—Jeremiah Flintwinch. The only glint of warmth comes from his old maid and nurse, Affery, now married to Jeremiah almost against her will—she has no will against the wishes of the “clever ones,” Mrs Clennam and Flintwinch. Clennam speaks to his mother of the watch left her by his father, and wonders whether it has some special, dark meaning for her. Later, as Affery prepares a bedroom for Arthur in the house, Arthur asks about a girl that he saw serving his mother, and Affery calls her “Little Dorrit,” who is a “whim” of Mrs. Clennam. Affery also lets him know that his old sweetheart, is now a widow.

That night, Affery has what Flintwinch calls “a dream”: she wakes to find not only her husband up, but talking to his double: an identical Flintwinch, who leaves the house carrying an iron box. Her husband finds her up, and threatens her with a beating if she should start “dreaming” again.

Arthur, the next morning, has the dreaded discussion with his icy mother. After giving up so much of his life to the business, he wishes now to relinquish his part in it. But first, he wishes to put right whatever wrong was weighing on his father’s conscience at the end.

“…is it possible, mother, that he had unhappily wronged any one, and made no reparation?”

Mrs Clennam resents the insinuation, implying that she knows nothing about it, and calls Flintwinch in to witness her undutiful son. She makes Flintwinch a partner in the business, and says that Arthur must never allude to the subject of his father’s guilty pleading again. Arthur decides to stay elsewhere.

Arthur is curious, however, about the young woman he sees again at his mother’s house, Little Dorrit. Knowing that it is unlike his mother to take a fancy or show kindness, he wonders whether Little Dorrit might have something to do with the guilty secret that seems to hover about the house of Clennam.

“Sometimes Little Dorrit was employed at her needle, sometimes not, sometimes appeared as a humble visitor: which must have been her character on the occasion of his arrival. His original curiosity augmented every day, as he watched for her, saw or did not see her, and speculated about her. Influenced by his predominant idea, he even fell into a habit of discussing with himself the possibility of her being in some way associated with it. At last he resolved to watch Little Dorrit and know more of her story.”

A story is then told, of a gentleman who made a poor investment and lost all his money, who entered the debtors’ prison—the Marshalsea—and whose child, a girl, was born there. This man, so long imprisoned, was to become known as “the Father of the Marshalsea.” His child, the “Child of the Marshalsea,” is now a young woman, Amy Dorrit. On the death of her mother, Amy, even as a girl, had begun to take responsibility for the family: she requests from one of the inmates, a milliner, to teach her needlework so as to earn some money outside the prison for her father. (While trying to keep up the pretense that she doesn’t “work,” as he is a “gentleman.”) Amy arranges for her older sister, Fanny, to begin taking lessons from a dancing-master, and to live outside the prison with their uncle. Amy also arranges for her brother to get work, but he proves inept at keeping a job. Finally, he ends up in debt himself, and becomes a prisoner.

“What her pitiful look saw, at that early time, in her father, in her sister, in her brother, in the jail; how much, or how little of the wretched truth it pleased God to make visible to her; lies hidden with many mysteries. It is enough that she was inspired to be something which was not what the rest were, and to be that something, different and laborious, for the sake of the rest. Inspired? Yes. Shall we speak of the inspiration of a poet or a priest, and not of the heart impelled by love and self-devotion to the lowliest work in the lowliest way of life!”

Arthur has seen Amy enter the Marshalsea and inquires about her of a man who is also entering, who turns out to be Amy’s uncle—not a prisoner—and Arthur asks to be introduced to Amy and her father, wishing to be of help. The uncle, Frederick Dorrit, only asks that Arthur not let his brother know that Amy works for Mrs Clennam, to keep up the pretense of leisured gentility. Up in William Dorrit’s room in the prison, Arthur observes all the ways in which Amy serves the family, including having brought her own food from work back to her father for his dinner. She has mended her sister’s clothes; Fanny comes to collect them.

Arthur gives Mr Dorrit a gift of money after the latter hints about how welcome such “testimonials” are. Arthur then catches Amy and tries to explain to her why he came; he only intended to help. Shy and embarrassed, she insists that he must leave before the final bell rings or he’ll be locked in for the night. They part. However, Arthur is too late. He meets with “Tip”–Little Dorrit’s brother Edward–who is now a prisoner as well, and he arranges for Arthur to pay for a room in the “Snuggery” for the night.

Arthur seeks out Amy and speaks to her, and they venture towards the Iron Bridge, which, because of its penny toll, is quieter than other areas. He reiterates that he didn’t mean to embarrass her by his visit of the day before, but only wished to help, and asks if she knows of the names of his father’s creditors. She only knows of a “Tite Barnacle.” But Amy also adds that she is not sure that her father would do well outside of the prison, where he is at least respected and understood; she also begs Arthur to try and understand him, and not to judge him as he would judge other men outside the prison. He understands. Amy also gives Arthur the name of a friend who can tell him more about her brother’s creditor, as she would love to see Tip at liberty. Then, Amy’s friend Maggy, a young woman who still believes she is ten years old—she had had a bad fever at the age of ten where she went to the hospital and loved it—runs up to Amy and Arthur, calling the former “little mother.” Amy is proud of Maggy’s ability to get some work to support herself, and even to read a little.

Arthur tries to get information on the Dorrit case out of that great public institution, the Circumlocution Office. Arthur circles his way in and out of several departments—who always refer him to other departments, and to fill out more forms—and ends up talking with Barnacle Jr, who refers him to his father’s home. Mr Tite Barnacle, however, sends him back to the Circumlocution Office, where he is advised to fill out even more forms. Arthur meets his old traveling friend, Mr Meagles, who is in an angry state for the sake of his inventor-friend, Mr Daniel Doyce, who has had no more luck in promoting his inventions of public beneficence to the Circumlocution Office, than Clennam has had in getting information. Doyce says that many inventors and entrepreneurs have had to go abroad for any success in their endeavors. The three men all have an errand to run in Bleeding Heart Yard, and venture there together.

We then turn our sights back to France, where Rigaud—now going under the name Lagnier—encounters his old cellmate, John Baptiste Cavalletto, at an inn. Cavalletto has been doing odd jobs since he was let out of prison a couple of days after Rigaud. Rigaud wishes to travel with him. Cavalletto, terrified, flees from the inn that night while Rigaud is asleep.

In Bleeding Heart Yard, Arthur visits the Plornish family, as Mr Plornish is the contact that Amy had given him in regard to her brother. They had also helped Amy to advertise her services—which is how Mrs Clennam discovered and hired her—and Amy uses their address as her mailing & residence. Once Mr Plornish—an old fellow debtor in the Marshalsea—realizes that Arthur’s intentions in helping the family are good, he advises Arthur of how to clear Tip’s debt so that he can be released.

Arthur visits his old acquaintance, Mr Casby—whose daughter, Flora, now a widow, was Arthur’s first love, but from whom Arthur was separated because of the disapproval of the family—in hopes of inquiring about the Dorrit case. But Arthur, in going there, can’t help but reminisce about his old, lost love, Flora. Seeing her again in person, however, Arthur is disappointed.

“Flora, always tall, had grown to be very broad too, and short of breath; but that was not much. Flora, whom he had left a lily, had become a peony; but that was not much. Flora, who had seemed enchanting in all she said and thought, was diffuse and silly. That was much. Flora, who had been spoiled and artless long ago, was determined to be spoiled and artless now. That was a fatal blow.”

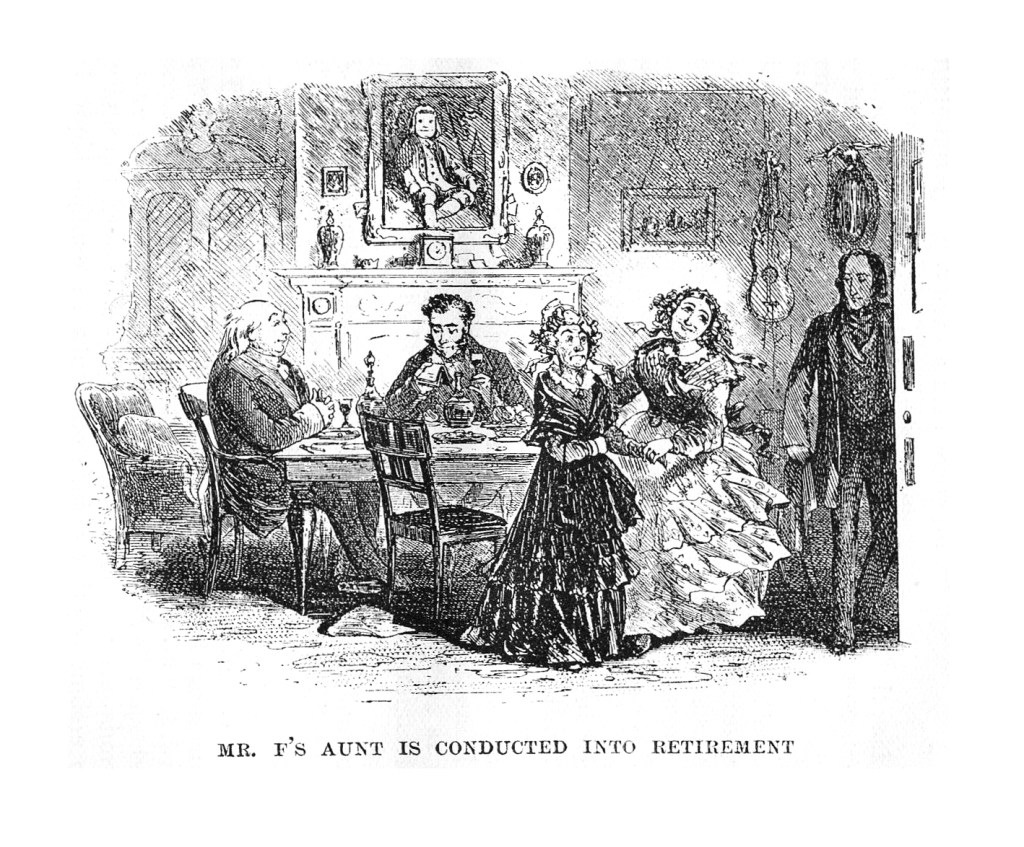

But Flora insists on being coaxing, flirtatious, and girlish with him, as though they are both renewing the old flame. Clennam dines with Casby, his daughter, Pancks—Casby’s hired man, who collects the rent from the tenants of Bleeding Heart Yard—and “Mr F’s Aunt,” the “legacy” left to Flora by her deceased husband, Mr Finching. Mr F’s Aunt seems to take a mysterious dislike to Arthur.

“There was a fourth and most original figure in the Patriarchal tent, who also appeared before dinner. This was an amazing little old woman, with a face like a staring wooden doll too cheap for expression, and a stiff yellow wig perched unevenly on the top of her head, as if the child who owned the doll had driven a tack through it anywhere, so that it only got fastened on…A further remarkable thing in this little old woman was, that she had no name but Mr F.’s Aunt…

“The conversation still turned on the receipt of rents. Mr F.’s Aunt, after regarding the company for ten minutes with a malevolent gaze, delivered the following fearful remark:

‘When we lived at Henley, Barnes’s gander was stole by tinkers.’ Mr Pancks courageously nodded his head and said, ‘All right, ma’am.’ But the effect of this mysterious communication upon Clennam was absolutely to frighten him.”

When Arthur leaves, he goes to the aid of a man who was hit by a postal coach. The man is a foreigner, but Arthur is able to understand and interpret. It proves to be John Baptiste Cavalletto. Arthur accompanies him to the hospital.

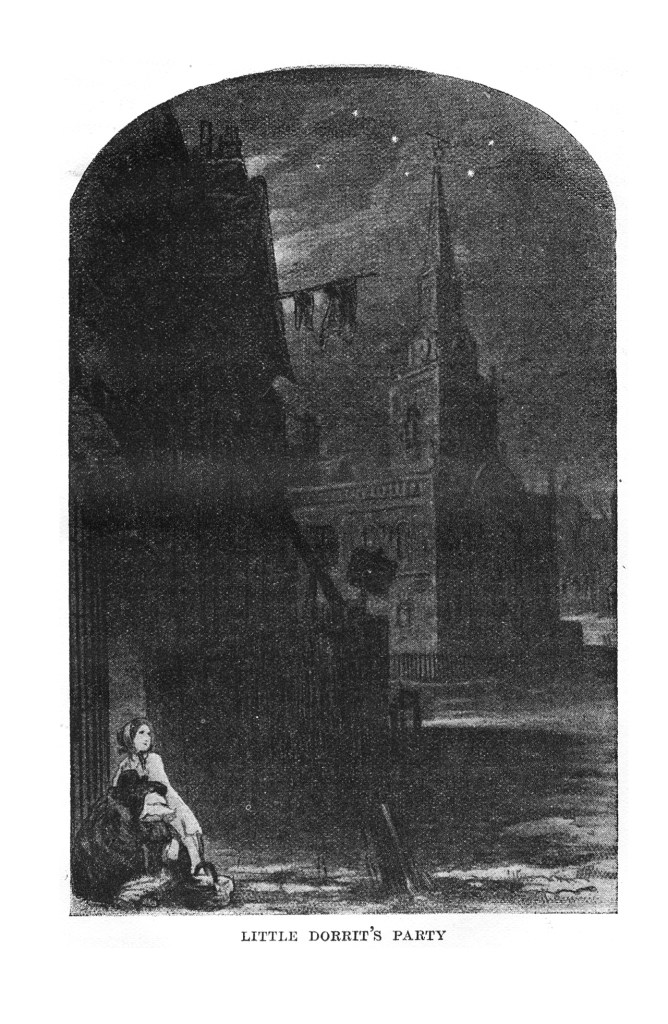

Around midnight, Arthur receives two surprise visitors at his lodgings: Little Dorrit, and Maggy. He fears that Little Dorrit is not dressed properly for the cold, and worries that she has been out so late. But she had just come from seeing her sister at the theater, and is used to walking about at night. Little Dorrit, who is not supposed to know who is the benefactor who cleared her brother of his debt, nonetheless communicates her thanks to Clennam, knowing that it was him. She also asks Arthur not to give her father money, and not to “understand” him when he seems to ask for it. Amy also asks Arthur not to accompany them back, but he follows at a distance until they are near the gate. As it is locked, however, they wander the streets and find rest at the church where Little Dorrit’s name is on the Register, and she rests her head on the old book until the Marshalsea opens again.

Back at the house of Clennam, Flintwinch and Mrs Clennam are arguing before Arthur arrives. Flintwinch, who had recently followed Little Dorrit back to the Marshalsea—says that he knows where she lives. Mrs Clennam doesn’t want to hear, and says that Little Dorrit can keep her secret.

Arthur meets up with Daniel Doyce on his way to visit the Meagles family, and they both venture together. Doyce is looking for a business partner; one who is better versed in the financial aspects of the venture. The Meagles family welcomes the men warmly. There are hints from Tattycoram that she has seen Miss Wade since their travels, and that that lady has been kind to her. Arthur asks Mr Meagles whether he might recommend him—Arthur—as a prospective business partner to Doyce. Arthur, meanwhile, tries to fight off the urge to fall in love with Pet, so much younger than him.

Arthur figures it was a good thing that he wouldn’t allow himself to fall in love with Pet, as her heart seems already given to a young, careless fellow and artist, Henry Gowan, whose presence makes Mr and Mrs Meagles uneasy. (Arthur later learns that this is a large part of their frequent travels—to try and help Pet get distance from him.) They are all joined by Clarence Barnacle—one of the savvier Barnacles, with the same careless ease as Gowan—for dinner. This particular Barnacle at least seems honest enough to admit that the workings of the Circumlocution Office are all humbug, though he himself is part of the system.

It has been a habit of Amy’s lately to walk on the Iron Bridge, and she is discovered there by her old playfellow and admirer, John Chivery, the young son of the turnkey. He is dressed up for the occasion. She is distressed to see him, knowing that he intends to declare his love; she asks him not to speak of the subject, and beseeches him with compassion not to come and find her anymore when she is walking at the Bridge, and says that she hopes he will find a good wife who is worthy of him.

Poor John, always imagining for himself various epitaphs, now imagines a far more dismal one, at some future date in St George’s churchyard:

“Here lie the mortal remains Of JOHN CHIVERY, Never anything worth mentioning, Who died about the end of the year one thousand eight hundred and twenty-six, Of a broken heart, Requesting with his last breath that the word AMY might be inscribed over his ashes, which was accordingly directed to be done, By his afflicted Parents.”

Discussion Wrap-Up (Weeks 1 & 2)

Miscellany & What We Loved; Reponses to the Intro; Opening Questions

What didn’t we love? Such marvelous characters, and some of Dickens’s greatest comic creations. Rob and I gushed about Flora:

We were thrilled to see Father Matthew back some extremely busy months! And he is loving the book so far:

He also highlights a few other favorite things:

Dana, after expressing her love for Boze’s introduction and the opening comments–as well as Anton Lesser’s audiobook!–welcomed Fr. Matthew back and is “enraptured” by Little Dorrit. “I believe it is rapidly becoming my favorite Dickens.”

Daniel then highlights some wonderful things about Boze’s introduction, and asks some great questions, a number of which will be addressed in the discussion:

I answer the one about the Francis Hopkinson Smith:

Little Dorrit’s Southwark: St George’s, the Marshalsea, the Iron Bridge

On Twitter/X, I reposted a thread about my visit to Little Dorrit’s Southwark in 2016. Click below and scroll down to see the pictures in full:

Dickens’s “Writing Lab”: “Messiness”–or Rather, the Method in the Madness; Prisons and Foreshadowings; Characterization; the “Social Bitterness” in the Novel

We discussed the opening at length, with our two jailbird characters in Marseilles; I talked of both the delightfully “messy”–strange would have been the better word–opening, and alluded to the convoluted end revelations, though they don’t dampen my love for this novel; it seems somehow part of the complicated world of Little Dorrit.

Lenny responds:

Chris finds that everything “hits the right mode and tone…giving us the foundational information we need”:

Lenny agrees:

And Dr Christian, on Twitter, adds a wonderful tweet in response to the conversation, referring to the messy-looking, but quite revised & thought-out, first page of Little Dorrit, “revealing the care and craft of the opening”:

What the opening establishes, as the Stationmaster argues here, is the “theme of imprisonment”:

Father Matthew agrees:

Father Matthew wonders whether Dickens had had an entirely different story in mind at first, but then considers that the opening is more deliberate and thematic:

“Still, my working theory is that the initial prison scene, like an overture, establishes the recurring central theme of the story. Almost all of the characters we have seen so far are imprisoned in one way or another — with the possible notable exception of Arthur Clennam. At the end of chapter nine, we get the repetition of the caged bird image from chapter one, like a musical motif reminding us of the overture. This is a story about prisons and prisoners, and our Little Dorrit ‘“’the small bird, reared in captivity,’”’ who has never yet spent a night outside her cage.”

~ Fr Matthew Knight

And there is so much more foreshadowing, as the Stationmaster considers:

Lenny responds:

And what of the marvelous characterization in this novel? Before we spotlight a few, Chris considers several of them and the “contrasts in selfishness and selflessness”:

And speaking of Mr Plornish, Lucy considers whether he comes to the heart of the social “bitterness” expressed by the novel:

“On this re-readthrough I’ve realised something new. I’ve had trouble puzzling out just where the social bitterness in Little Dorrit is going, and I think Plornish’s soliloquy in the cab with Arthur in chapter 12 (after they have redeemed Tip’s debt) is key. And it ties in with how the novel was to be called ‘Nobody’s Fault’, which I never understood really.

Plornish is talking about being blamed for being poor – being blamed for being ‘improvident’. I’ve **’d what I think are the key passages. I know Plornish is a gentle, ineffectual character, but these words I think carry what Dickens is saying.

‘…On the way, Arthur elicited from his new friend a confused summary of the interior life of Bleeding Heart Yard. They was all hard up there, Mr Plornish said, uncommon hard up, to be sure. Well, he couldn’t say how it was; he didn’t know as anybody could say how it was; all he know’d was, that so it was. When a man felt, on his own back and in his own belly, that poor he was, that man (Mr Plornish gave it as his decided belief) know’d well that he was poor somehow or another, and you couldn’t talk it out of him, no more than you could talk Beef into him. Then you see, some people as was better off said, and a good many such people lived pretty close up to the mark themselves if not beyond it so he’d heerd, that they was ‘improvident’ (that was the favourite word) down the Yard. For instance, if they see a man with his wife and children going to Hampton Court in a Wan, perhaps once in a year, they says, ‘Hallo! I thought you was poor, my improvident friend!’ Why, Lord, how hard it was upon a man! What was a man to do? He couldn’t go mollancholy mad, and even if he did, you wouldn’t be the better for it. In Mr Plornish’s judgment you would be the worse for it. Yet you seemed to want to make a man mollancholy mad. You was always at it—if not with your right hand, with your left. What was they a doing in the Yard? Why, take a look at ‘em and see. There was the girls and their mothers a working at their sewing, or their shoe-binding, or their trimming, or their waistcoat making, day and night and night and day, and not more than able to keep body and soul together after all—often not so much. There was people of pretty well all sorts of trades you could name, all wanting to work, and yet not able to get it. There was old people, after working all their lives, going and being shut up in the workhouse, much worse fed and lodged and treated altogether, than—Mr Plornish said manufacturers, but appeared to mean malefactors. Why, a man didn’t know where to turn himself for a crumb of comfort. As to who was to blame for it, Mr Plornish didn’t know who was to blame for it. He could tell you who suffered, but he couldn’t tell you whose fault it was. It wasn’t his place to find out, and who’d mind what he said, if he did find out? He only know’d that it wasn’t put right by them what undertook that line of business, and that it didn’t come right of itself. And, in brief, his illogical opinion was, that if you couldn’t do nothing for him, you had better take nothing from him for doing of it; so far as he could make out, that was about what it come to. Thus, in a prolix, gently-growling, foolish way, did Plornish turn the tangled skein of his estate about and about, like a blind man who was trying to find some beginning or end to it; until they reached the prison gate. There, he left his Principal alone; to wonder, as he rode away, how many thousand Plornishes there might be within a day or two’s journey of the Circumlocution Office, playing sundry curious variations on the same tune, which were not known by ear in that glorious institution. …’ (from the end of Ch. 12, ‘Bleeding Heart Yard’)

And then when Little Dorrit comes to visit Arthur in his rooms two chapters later, this extraordinary passage in CD’s voice breaks through from describing Little Dorrit’s reverie as she passes through Covent Garden:

‘ …where the miserable children in rags among whom she had just now passed, **like young rats, slunk and hid, fed on offal, huddled together for warmth, and were hunted about (look to the rats young and old, all ye Barnacles, for before God they are eating away our foundations, and will bring the roofs on our heads!)** …’ (ch 14, paragraph 2).

That’s pretty clear, isn’t it. The young rats who the Barnacles should deal with as vermin.

So for me, the focus of Dickens’s wrath here is not just on snobbery and vacuity and hypocrisy, but on society *blaming* the poor for being poor.”

~Lucy S. comment

The Stationmaster is intrigued by Mr Meagles:

And shall we raise a glass to our delightful John Chivery?

Character Spotlight: Arthur Clennam

Is Clennam a kind of detective, “a ‘searcher’ for a number of ‘things’…family secrets”? Lenny considers his characterization:

Chris quotes some of the poignant, reflective passages about the solitary Arthur–which I will only quote a passage of here:

Reflecting on the above, Chris continues:

Character Spotlight: Amy Dorrit; or, “Nell Redux”

And as to our female lead, everyone appears to be touched and intrigued by Amy, a.k.a. “Little Dorrit,” including the Stationmaster, who finds her full of compassion but “less delusional about her unworthy father and siblings”:

Lenny considers Amy as perhaps a more mature Little Nell from The Old Curiosity Shop–a kind of “Nell Redux”:

Here is a beautiful passage from Chris’s reflection on Amy Dorrit:

Character Spotlight: Miss Wade

Dana considers the eerie quality of the passages revolving around the enigmatic Miss Wade in the opening:

Lenny responds, wondering whether Miss Wade here is “a kind of extension of the narrator”:

Chris is not a fan of Miss Wade, perhaps, she says, because Dickens writes her so well. She seems to be in the vein of some of Dickens’s other women, and the Stationmaster asks about this:

Chris clarifies:

Dickens as “The Haunted Man”: Historical Context and Dickens’s Involvement in Wilkie Collins’s Play, The Frozen Deep

With almost every one of our novels, especially as we have moved into the autobiographical David Copperfield and now this wonderful middle period (the last of what the Stationmaster considers a kind of “trilogy”: Bleak House, Hard Times, Little Dorrit), we’ve considered the ways in which Dickens’s own life and history is coming up, including the marriage to Catherine which is falling apart.

Deborah Siddoway gave us some wonderful additional context for Dickens’s theatrical involvement and state of mind at the time, in response to one of Daniel’s questions at the outset about the Wilkie Collins play, The Frozen Deep (which was to greatly influence our next work, A Tale of Two Cities).

Deborah writes:

“During 1856, as he continued writing the instalments for Little Dorrit, Dickens also commenced work on the putting on of a play written by Wilkie Collins. That play was called The Frozen Deep. It would prove to be the catalyst that would compel Dickens to act upon his searing sense of unhappiness and domestic ennui, and separate from his wife.

As Collins neared completion of the script in October 1856, Dickens grew, as Lycett observes, ‘visibly excited’, growing a beard in anticipation of the role of Richard Wardour, the Arctic explorer of the terrible icy regions, and set about transforming the school room of his home, Tavistock House, into a suitable theatre. In January 1857, a select audience, comprising the ‘highest celebrities in law, art, and fashion’, including the Chief Justice of England, the president of the Royal Academy, and professional reviewers, watched an amateur performance of this play, with Dickens ‘rending the very heart out of [his] body’ playing the role of Richard Wardour, a man who is defined by his appetites, including his love for the character of Clara Burnham. It is a clever play on names, the ardour of Wardour being disguised within his own name, and Clara’s surname, a close homophone for ‘burn him’ evoking a sense of her power over him, her potential to consume him. In the play, Wardour was a man who had been disappointed in love, believing himself to be engaged to Clara, who was engaged to another man, Frank. As Tomalin notes, from the very outset of the putting on of the play, Dickens was intent on throwing himself into the part of a man who overcomes his own wickedness and ends by making the supreme sacrifice. In taking on this role, Dickens was able to find some relief from his marital unhappiness. Months after the final performance, he would still refer to the relief that his part in the play had given him.

Hager states that the story of The Frozen Deep is one of ‘renunciation and heroic self-sacrifice. It is also a story of unrequited love, broken engagements, and a kind of ferocious self-discipline’. It was a story that spoke to the very heart of the struggles that Dickens himself was enduring at that time. Tomalin observes that the plot of The Frozen Deep was ‘preposterous and the writing hardly better’, but it was the performance, not the script, that excited Dickens, and he was able to transcend the limits of that script. Brannan argues, in his analysis of the 1857 script that this was because Dickens’s conception of the play was independent of Collins’s words, growing from his sense of dissatisfaction with his personal life and his increasingly painful marriage.

In the play, Dickens, through giving voice to the character of Wardour, who values the icy plains of the Arctic because they have no women in them, is able to indulge in a diatribe of blaming women for his unhappiness, the ‘disappointment which had broken [him] for life, though such lines as ‘The only hopeless wretchedness in this world, is the wretchedness that women cause,’ turning to the audience, commanding them to look at him:

Look at me! Look at how I have lived and thriven, with the heart-ache gnawing at me at home… I have fought through hardships that have laid the best-seasoned men of all our party on their backs.

As the play continues, Wardour despairs over his own thoughts, in an echo of Dickens’s own inner turmoil:

If I could only cut my thoughts out of me, as I am going to cut the billets out of this wood!… I don’t like my own thoughts – I am cold, cold, all over.

Here speaks, as Ackroyd observes, the boy, the adolescent and also the man, each stage of Dickens’s life marked by the supposed enmity or failure of women, including his mother, his sister, Maria Beadnell, and his wife. They are lines that seem to have come from some ‘deeper source within him’. Through the conduit of the stage, Dickens was able to vocalise his own misery. Dickens acted the role with such intensity that he was often near collapse after the performances, and he relished in the reaction of his ‘excellent’ audience, commenting to his friends that he had never seen audiences so affected, and delighting in the ‘wonderful power of crying’ he was able to call from them. There can be no doubt that Dickens carried the play, his ‘finely executed’ performance being lauded by the critics, as evidenced by the fact that later productions of the play failed. When the play was revived in 1866, without Dickens in the role of Wardour, it flopped, although at the time Collins believed that the failure of the play might have had something to do with the timing, being forced onto the stage in October, rather than closer to December when it may have benefitted from the Christmas market. It was also reviewed and rewritten by Collins in 1874, but again, failed to gain any of the popular or critical success it had enjoyed in 1856 or 1857 when Dickens had played the part of Wardour. Tomalin suggests that it was the presence of Dickens that made up for the defects of the play. Dickens, and his innate misery, were the driving forces behind the initial success of the play.”

~Deborah S.

Daniel responds:

Daniel also gives us an insightful definition of the word “haunted” from the poet David Whyte, of which I’ll highlight a section here:

Doubling: Two “Gentlemen”

Dickens is the master at “doubling”–and I bring up a particularly unlikely kind of doubling that I see happening here:

Chris responds, as to the true nature of a gentleman:

Lenny brings up a favorite film, and wonders whether the allusion suggests that Rigaud is a psychopath. (I would add: YES.)

Lucy responds that this whole theme–putting status over human connection–is part of the “heart” of Little Dorrit:

A Look-Ahead to Weeks 3 & 4 of Little Dorrit (7-20 November, 2023)

This week and next, we’ll be reading the rest of Book I (Chapters 19-36) of Little Dorrit. These chapters were published monthly (installments VI-X) between May and September, 1856.

Feel free to comment below with your thoughts, or use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on Twitter/X.

If you’d like to read it online, you can find it at a number of sites such The Circumlocution Office; you can download it from sites such as Gutenberg.

Whew, Rach: what an amazing recapitulation of the first two weeks of our reading experiences and commentary! Your in depth summary of the first 18 chapters of LD is, once again, hugely helpful–as it puts so much into perspective that at least I tend to lose sight of with my focus on just chunks of the novel. And your marvelous recapitulation of our group’s “work” is equally as useful because it highlights so many ideas that are important to us for our understanding of the novel’s themes and the various and strange characters that Dickens throws at us. Wow, what a great job. Thanks SO much!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Dear Lenny! I meant to respond right away…your comments mean so, so much. Thank YOU! It is such a huge pleasure!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

BTW, in Rach’s summary of our group’s commentaries, I was once again blown away by the in depth analysis that Chris does of Amy and her abilities to function as the young organizer and provider for the well being of her family, as well as Lucy’s remarks on Plornish’s long and important remarks on what it’s like being poor in the Bleeding Heart Yard. Such good stuff, here!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Wonderful summary as always, Rach and great discussion points. Have been terribly busy at work but Have been keeping up with the reading and the tweeting of tweetable quotes.

As a first time reader, I tread carefully among the comments as I want to avoid spoilers!

Next two weeks busy too, so will do the best I can. Just be assured I’m keeping up as best I can.

Such a gorgeous, beautiful novel. Some chapters so good I have gone back and read them again before moving on 😀

Also – The Juliet Stevenson audiobook is wonderful. From the off she hits the right tone, and her voices for Rigaud and Cavalletto replete with accents, really do sound as if they were performed by a man! Astonishing.

I was very struck by Miss Wade. It seemed to me she might play a similar symbolic role to Miss Flite, with her somewhat random utterances having a deep significance theme wise. Wouldn’t be surprised if she too has birds with creepy names.

Dickens obviously had early plans for Miss Wade. From the Forster biography:

“I don’t see the practicability of making the History of a Self-Tormentor, with which I took great pains, a written narrative. But I do see the possibility of making it a chapter by itself, which might enable me to dispense with the necessity of the turned commas. Do you think that would be better? I have no doubt that a great part of Fielding’s reason for the introduced story, and Smollett’s also, was, that it is sometimes really impossible to present, in a full book, the idea it contains (which yet it may be on all accounts desirable to present), without supposing the reader to be possessed of almost as much romantic allowance as would put him on a level with the writer. In Miss Wade I had an idea, which I thought a new one, of making the introduced story so fit into surroundings impossible of separation from the main story, as to make the blood of the book circulate through both. But I can only suppose, from what you say, that I have not exactly succeeded in this.”

LikeLiked by 2 people

Rob: I like (with a big smile) your “birds with creepy names”! And as I wrote about her earlier, she seems to be a kind of extension of her narrator’s philosophical interpolations. But although Miss Wade seems to be a social misfit, she stands for an original female thinker/speaker who gets right to the heart of the matter with her observations about the encounters and clashes people have with other people. Maybe she stands for something like the voice of “fate” and the inevitability of transactions that all of us will experience in our lives. The fact that Rach leads off her summary/critical encapsulations with this key remark of Miss Wade–“In our course through life we shall meet the people who are coming to meet us, from many strange places and by many strange roads…and what it is set to us to do to them, and what it is set to them to do to us, will all be done”–seems to me to be super important! And in her early “dressing down” of Pet/Minnie shows her mental acuity, as she perceptively observes this young woman’s superficiality.

So here’s what I now think: in this novel’s THEMATIC context, she seems to operate as a kind of soothsayer, on the one hand, but also as a kind of Greek chorus, on the other. Here, then, may be the “symbolic” value which you might attach to her, Rob. Yet, on the novel’s REALISTIC plane, this strange figure begins to be more of a actual “personality” in the narrative when she makes her heavily strident attack on the Meagles and “rescues” Tattycoram from what she believes is a totally demeaning and negative situation as a servant to Minnie. At this point, she takes on maybe a combined symbolic and “real” personage role–as a feminist saving another young woman from what she (Miss Wade) believes is a kind of enslavement.

So in sum, as I write this, I’m thinking that I kind of LIKE her– regardless of her enigmatic and polarizing role in the novel.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sometimes I think of Miss Wade as being like Shylock from The Merchant of Venice, a character whom the author intended to be totally evil but with whom modern audiences tend to sympathize and even agree with them on some issues instead of the protagonists. Sometimes I also think Dickens did intend us to sympathize with her on some things. There’s a possibility that Shakespeare also wanted us to sympathize with Shylock on some level, but I find it more likely that Dickens wanted us to do so with Miss Wade since he does express some concerns similar to hers in other books. Like I said, she’s an interestingly weird character.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I forgot to mention that I also think it’s more likely we were mentioned sympathize with Miss Wade on some level than with Shylock because Miss Wade, for all her bitterness, doesn’t plan on carving up anyone’s flesh. Well, not that we know of anyway. LOL

LikeLiked by 2 people

Stationmaster…love the Shakespeare comparisons! I’m pondering that now. I think, in a way, we are justified with sympathizing with Shylock because if he is asking for his pound of flesh, it is the society around him that has taught him to do so. I’m so curious now as to how everyone will react about Miss Wade…has society, or those who have brought her up, justified her cynicism? Or has she created her own hell? Hmmm…so much to ponder, & now there are some passages I want to reread in this light.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Stationmaster: the productions of THE MERCHANT I’ve see tend to present Shylock in radically different ways. One will show him as a sympathetic character, and the audience tends to be totally outraged by the main characters’ treatment of him throughout and at the end of the play, while another production will present him as hateful and we (in the audience) then think he received the punishment he deserved!

In referring to your comment below, I’d like to say that in a way, Miss Wade’s comments are pretty darn piercing, and could cut people up pretty badly. Pet certainly feels the needle and later Meagles will get pretty carved up by her comments about the family’s treatment of Tatty.

LikeLike

Lenny & Rob, fantastic comments! Rob, I loved the passage from Forster–that helps so much. Lenny, I *love* the kind of “Greek Chorus* idea; she does seem somehow detached enough (though we’ll see whether or not she is truly detached as it goes…) to give a big-picture analysis. But is she a kind of unreliable narrator, too–of her own story, of Tatty’s? We shall see…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh boy! Now you’ve got me worried! But I must say, regardless of her reliability, I do love what I see is her anger! In fact, I wish more characters would get really angry in this novel. So much tiptoeing around, so much backing down. Time for some kind of revolution rather than mere subversion without making a social impact. This society of giving up must have totally rankled Dickens. Such passivity in the face of adversity and social stratification! Ugh!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love the description of Mr. Dorrit at the beginning of Chapter 19.

“The time had been when the Father himself had wept, in the shades of that yard, as his own poor wife had wept. But it was many years ago; and now he was like a passenger aboard ship in a long voyage, who has recovered from sea-sickness, and is impatient of that weakness in the fresher passengers taken aboard at the last port. He was inclined to remonstrate, and to express his opinion that people who couldn’t get on without crying, had no business there.”

It’s interesting how he projects his weaknesses onto his brother as a coping mechanism.

It’s also interesting to compare and contrast Little Dorrit with Madeline Bray, a Dickens heroine in a similar situation from an earlier book. As much as Little D loves her father and wants to help him, she never seems to consider giving into his pressure and encouraging John Chivery’s advances. This is especially notable in that John Chivery isn’t a bad guy like Arthur Gride and her father isn’t asking her to marry him, just not explicitly reject him. Of course, the flipside of that is Arthur Gride was offering to free Madeline Bray’s father whereas the Chivery family could, at most, make William Dorrit’s slightly cushier and he’s not nearly as skillful a manipulator as Walter Bray was. But it does emphasize to me how much more complex Little’s Dorrit character is. (I’m not bashing Madeline Bray BTW. I think she’s great for her own purposes.)

I don’t know much about historical theaters like the ones where Fanny and her uncle work, but I love Dickens’s description and how he implies the people who work there are trapped like the Marshalsea prisoners.

“Little Dorrit was almost as ignorant of the ways of theatres as of the ways of gold mines, and when she was directed to a furtive sort of door, with a curious up-all-night air about it, that appeared to be ashamed of itself and to be hiding in an alley, she hesitated to approach it; being further deterred by the sight of some half-dozen close-shaved gentlemen with their hats very strangely on, who were lounging about the door, looking not at all unlike Collegians.?

I love the character of Mrs. Merdle and how obviously hypocritical she is with her talk of how she wishes she and her guests could revert to a primitive “natural state” while she’s living in this big fancy house and wearing this expensive clothing and jewelry. (Remember how Squeers and Snawley eulogized nature in Nicholas Nickleby?) It seems like her parrot always shrieks when she says something obviously untrue, much like the way Mr. Dorrit “hems” before saying something of which he’s ashamed.

In Little Dorrit, Dickens is using the classic fairy tale motif of two bad older siblings and the good youngest sibling who’s an underdog. But Tip and Fanny Dorrit are a bit more complex than we expect from evil siblings in fairy tales. Dickens writes that Tip “he respected and admired his sister Amy” but “The feeling had never induced him to spare her a moment’s uneasiness, or to put himself to any restraint or inconvenience on her account; but with that Marshalsea taint upon his love, he loved her. The same rank Marshalsea flavour was to be recognised in his distinctly perceiving that she sacrificed her life to her father, and in his having no idea that she had done anything for himself.” And it’s hard to imagine Cinderella’s stepsisters or Beauty’s sisters hugging her and crying as Fanny does to Little Dorrit. It’s interesting that Fanny sees accepting Mrs. Merdle’s bribery as a way of getting revenge on her. You’d think she’d be too proud to do so. I guess, like her father, she needs the money but can’t admit it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another doubling observation, and another British engineer who had to take his inventive skills to Europe, like Doyce.

First, Young Barnacle being unable to take his eyes from Arthur’s face at dinner at the Meagles’s in Twickenham doubles with Mrs F.’s aunt at Flora’s – except Young Barnacle is dumbfounded and outraged, while as we know, Mrs F. is just terrifying.

And then Doyce’s career path across Europe – from the Clyde to Lyons to Germany to St Petersburg. Also in the 1850s, as Little Dorrit was being written, there was another British engineer from Bolton, Robert Whitehead, who worked his way across Europe via Toulon, then Milan, to Trieste on what was then the Austrian Adriatic coast, where he invented the torpedo!! In 1856 he was running a metal foundry producing steam boilers for the Austrian navy, and in the 1860s, he got together with another engineer and they invented and trialled the torpedo for the Austrian Imperial Naval commission. Which proved a very popular and profitable invention.

There’s an amazing cartoon from Punch of 1877 of Whitehead presenting the half-human, half-fish figure of Torpedo to Britannia, captioned, Fiat experimentum- ! If I can figure out how to attach it, I will.

What’s more, Whitehead’s granddaughter Agatha married an Austrian war hero from the Austro-Hungarian navy called Georg von Trapp, who had made his name as a submrine commander sinking Allied ships in the First World War using those torpedoes. And guess what – that Captain von Trapp is *the* Captain von Trapp of, yes, *The Sound of Music.* Agatha produced seven children and died, and Maria Augusta von Trapp was hired to tutor the children, married him, and we know the rest.

We came across all this in the Maritime museum in Split, Croatia, on holiday last summer.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Rach, Can you advise me how to attach this image? Or I can email it to you and you can attach. It’s amazing.

Had Dickens heard of Whitehead? Seems doubtful, but clearly it was an established career path.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lucy, I love this story & doubling!!!

As to the image…what I’ve been doing is somehow finding a way to create a link to it. So, if you’ve shared it on twitter, you can link to your tweet, or, say, if you save the image to your google photos, you can create a link to that image, and share the link here. I’ve done both ways 🙂 (I DO wish you could simply attach an image…it seems odd that one can’t do that in the comments! Bah humbug! 😉 )

LikeLike

Okay, trying to paste a link to this via Twitter:

https://x.com/LucySetonW/status/1726190334189936701?s=20

LikeLike

Finally managed it. The cartoon I mentioned of Daniel Doyce’s real-life contemporary is at this link:

https://x.com/LucySetonW/status/1726190334189936701?s=20

(Sorry for the many previous tries.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’ve got to love this description!

“Mrs Merdle’s first husband had been a colonel, under whose auspices the bosom had entered into competition with the snows of North America, and had come off at little disadvantage in point of whiteness, and at none in point of coldness.”

Chapter 21 is where the book really leans into the satire of Society and starts developing the theme that wealth doesn’t solve every problem but even creates some of its own. Dickens also acknowledges though that being financially insecure like the Plornishes and the other residents of Bleeding Heart Yard is no picnic.

It’s possible the book later clarifies this, and I can’t remember right now but does Mrs. Chivery really believe that Little Dorrit is only holding back from her son because her family would disapprove or is she lying to Arthur Clennam, believing that if he advocates the match, Little Dorrit will agree?

Daniel Doyce isn’t the most memorable character in the book or anything, but he interests me in the context of Dickens’s oeuvre. In his last book, Dickens vilified the mangers of big businesses. Here he makes Doyce and Clennam heroes. Hard Times also arguably gave negative connotations to science and technology whereas Little Dorrit positively portrays an inventor and protests negative stereotypes about them. I’m not suggesting Dickens’s worldview underwent a sudden and drastic change between the two books BTW. I think the two of them show that for all his partisanship, he could see multiple sides of certain issues.

In our discussion of David Copperfield, I also defended Dickens against criticisms of making marriage and motherhood the only acceptable goals for his female characters. My defense wasn’t that Dickens doesn’t do this but that he also does it for his male characters, the protagonists anyway. It’s not like any of them have big dreams of becoming an astronaut or whatever and the big emotional resolution is them becoming astronauts. It’s always them getting married and (eventually) becoming fathers. Their getting jobs is seen a means to an end and the male characters most invested in their jobs, like Scrooge or Bounderby, are the really negative ones. Arthur Clennam’s story in Little Dorrit is arguably something of an exception. Dickens devotes a good bit of space to his starting a business with Doyce and while it’s not the main goal of the story, it feels like we’re supposed to admire him for it. In a way, you could say he’s not that different from Bounderby, wanting to break away from his mother and become a self-made man. But unlike Bounderby, he’s…you know, a decent human being.

Flora’s initial goal in helping Little Dorrit seems to have been impressing Arthur Clennam but heartwarmingly she quickly becomes genuinely attached to her. No doubt she’s a much friendlier employer than Mrs. Clennam.

In Chapter 24, Little Dorrit expresses her state of mind with an extended metaphor (the story she tells Maggy of the tiny woman, the princess and the bright shadow.) I believe she’s the only Dickensian protagonist to do so apart from the three narrators, David Copperfield, Esther Summerson and Pip and Esther felt like she was forced to narrate against her inclination and personality. This unexpected poetic streak cements Little Dorrit as one of my favorite leads in any of Dickens’s books.

What should we make of the Ruggs? They seem genuinely helpful, but Dickens’s tone is somewhat cynical as he describes them. He implies that most unmarried men are afraid of Miss Rugg, thinking she might sue them for breach of promise as she did the infamous baker. But that could be taken as reflecting badly on them for negatively stereotyping her. However, the fact that she feels like laughing at John Chivery’s emotional distress seems to imply her own was faked and she really is just a fortune hunter. Then again, Dickens also seems to want us to laugh at John Chivery every now and then.

Similar to what I wrote before about Mr. Meagles, Dickens sympathizes with Bleeding Heart Yard’s residents and portrays them as victims of people like Casby, the Barnacles and the Stiltstalkings, as Lucy touched upon, but he doesn’t turn a blind eye to their bigotry toward foreigners. In fact, he clearly condemns it. Even after they come to accept and like Cavalletto, it’s stressed that they still treat him very condescendingly. Fortunately, he doesn’t seem to mind at all.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Good Heavens, Stationmaster, you cover so much ground here and raise so many issues–that my head is just spinning! It seems like each of your paragraphs with their important ideas, deserve even more paragraphs which, of course, would spawn even MORE ideas. Almost a book’s worth of good stuff here.

As I think for a while about all that you’ve presented, I begin to realize that embedded in all of your commentary is a virtual catalog of female characters. And each of these women is so wildly different from the other and, when taken as a whole, represent different strata in the social makeup of this novel.

Mrs. Merdle, Mrs, Chivery, Flora Finching, Miss Ruggs, Mrs. Clennam, Maggy, Amy Dorrit–all define key ideas and have various and unique functions in this novel. Just about all of them are involved in some kind of personal relationship with the men in their lives–relationships themselves which give rise to these womens’ “places” as either victims OF or assertive IN their relationships with various male characters. That is, they may become more or less passive recipients of male action toward them, may become aggressive in their behaviors toward men, or may be merely pawns in the Patriarchal order of things in this novel. Or an interesting combination of all three possibilities. Mrs. Merdle, for example, has seemingly accepted her role as her husband’s “bosom”–where upon he can hang various kinds of bling denoting his higher social status (she does become a kind of buxom trophy wife), but at the same time she can take the initiative to stop the possible marriage between her stepson and Fanny Dorrit. Her status as a wealthy man’s wife gives her a kind of clout which she is more than willing to use to get what she believes is her rightful way in the transaction she has with Fanny. She can buy the younger woman off!

The most complicated of all these women, is, of course, Amy, who plays SO many roles as the novel progresses, and whose character makes for an almost dizzying complexity. At some points in these early stages of the novel she comes off as a kind of passive “victim” (of her father, of Pancks, of Arthur) as various men assert themselves against her; but at the same time, she can assert herself when, for example, at the bridge, she resolutely rejects the proposal of the love-lorn Mr. Chivery. Yet there are so many other sides to her character–her pride, her work ethic, her love for her father, her caring attitude toward her brother and sister, her innocence, paranoia, and complex relationship with Arthur. Earlier in my reading, I saw her more as an extension of Little Nell, but now I’m beginning to see that her personality is far more complex than Nell and that her roles in LD make her a far more prominent and “useful” character.

Ultimately, then, Stationmaster, what to make of all these women in the larger scheme of things in LITTLE DORRIT. Does this become a kind of “womens” novel–as we see happening in NICKLEBY, DOMBEY and COPPERFIELD–where ultimately they rise to challenge the Patriarchs, or do they play, ultimately more passive roles, perhaps the victims of a male oriented society? As we’re just getting started, of course, It remains to be seen….

LikeLiked by 2 people

FWIW, I’ve read this book three times by now, I think, so any insights in my comments are the results of that experience though there are some things in them that just occurred to me on this read. I’d almost advise you not to read what I write until you’ve read the whole of Little Dorrit for yourself. I don’t want to unduly influence anyone’s interpretation.

But thank you for your kind words! I’m really enjoy reading what you comment (and what everybody else is saying) too.

LikeLiked by 2 people

“Yet there are so many other sides to her character–her pride, her work ethic, her love for her father, her caring attitude toward her brother and sister, her innocence, paranoia, and complex relationship with Arthur. Earlier in my reading, I saw her more as an extension of Little Nell, but now I’m beginning to see that her personality is far more complex than Nell and that her roles in LD make her a far more prominent and “useful” character.”

Lenny, you said it. Amy is fabulous. Perhaps partly because she is so often described from the outside, as the author & other characters see her, & in her actions. There is so much Dickens *doesn’t* say – none of the usual sentimental or supposedly ‘feminine’ tropes. And when her thoughts are represented, they’re worth hearing. Those letters in part two!

She’s wonderful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s an interesting theory as to why Little Dorrit maybe works better than similar Dickens characters. Dickens probably couldn’t see things from the perspective of a “people pleaser” but he had witnessed others display patience and self-sacrifice and he admired them from the outside. Reading the book, we’re kind of in Arthur Clennam’s place, admiring Little Dorrit.

LikeLike

As Boze mentioned in his “Introduction”, “Little Dorrit” was originally to be titled “Nobody’s Fault”. Lucy also discussed this referencing Mr Plornish’s comments in Bk 1 Ch 12. According to John Forster, “The book took its origin from the notion [Dickens] had of a leading man for a story who should bring about all the mischief in it, lay it all on Providence, and say at every fresh calamity, ‘Well, it’s a mercy, however, nobody was to blame, you know!’” (Forster, Vol 2, Bk 8, Ch 1) The notion of such a leading man never came to fruition as Dickens progressed in his writing, and by the time of publication “Little Dorrit” took the honors as title. This name change bespeaks the shift of the novel’s focus from a narrow “‘one idea and design’ of social criticism” to a broader view of “the optimism about humanity which sets the rest [the Nobody] in perspective”. (Butt & Tillotson 230) Thus the novel, while highly critical of Society and Government, is more focused on the hope that lies in the individual’s choice to do what is right, to behave charitably, and to consider oneself through consideration of others.

“Nobody” is an interesting character whose nature is to be silent, intangible, pervasive. It certainly permeates the novel in the narrow, social criticism sense via the Barnacles, the Circumlocution office, and many of the characters’ avoidance of reality. It is unfeeling and cruel as described by Mr Plornish. Yet “Nobody” also finds its way into the broader view of optimism where it retains its silence and intangibility but takes on a decidedly antithetical nature by becoming individualized and full of feeling and benignity.

This “Nobody” appears in Arthur’s courtship, if you will, of Pet. (See Bk 1 Chs 16, 17, 26, and 28 – “Nobody’s Weakness”, Nobody’s Rival”, “Nobody’s State of Mind” and “Nobody’s Disappearance”, respectively.) In attributing his feelings for Pet and Gowan to “Nobody”, Arthur gives himself distance from himself to contemplate his feelings and their implications without imposing them on anyone. His courtship is completely internal and directed by Arthur’s genuine (to use Gowan’s word) desire to do what is right, to behave charitably, and to consider himself through consideration of others. When it is clear that Pet and Gowan will marry, Arthur bows out chivalrously with no harm done to anyone but himself. Had “Arthur” rather than “Nobody” fallen in love with Pet and seen Gowan as a rival the love would have been spoken and there would have been scenes, confrontation, and hurt. “Nobody’s Fault” here becomes a virtue.

Amy also employs this “Nobody” to help her through her own love-related struggle though she names it “the poor little tiny woman” of the fairy tale she tells Maggie in Ch 24. Amy has more difficulty dealing with her emotions than does Arthur, perhaps because she is so unused to considering her own needs and wants. John Chivery’s proposal, though I think not unexpected, comes in the midst of her struggle to deal with her feelings for Arthur. John though shy to speak seems to think – as do her father and Mr & Mrs Chivery – it a foregone conclusion that Amy will simply accept his proposal. John is stunned and mystified – and the three parents are angered – when Amy refuses the offer. To her credit, Amy gently but emphatically lets John down (Ch 18), but she actually has to reprimand, again gently but emphatically, her father for his selfish reaction to her decision – “Only think of me, father, for one little moment!” (Ch 19)

Amy’s difficulty is compounded by Flora’s effusive description of her own love affair with Arthur and her not so subtle girlish wish that it may one day be revived. Arthur himself dispels the idea of his being in love with Flora but almost in the same breath he increases her distress by confessing his now-over love for Pet and his conviction that he is now too old for romantic love: “O! If he had known, if he had known! If he could have seen the dagger in his hand, and the cruel wounds it struck in the faithful bleeding breast of his Little Dorrit!” (Ch 32) I keep finding myself saying, “blind, blind, blind!” (“David Copperfield, Ch 35) So Amy, like the tine woman, intends to keep the “great, great treasure” of her love for Arthur in her own “secret place”, expecting “it would sink quietly into her own grave, and would never be found” out by anyone. (Ch 32) After all, it’s nobody’s fault.

Two unrelated comments:

A favorite line, regarding the stage door at the theatre where Fanny dances: “a furtive sort of door, with a curious up-all-night air about it, that appeared to be ashamed of itself and to be hiding in an alley”. (Ch 20)

Mrs Merdle’s parrot and Mr F’s Aunt are quite like Barnaby Rudge’s raven, Grip, in that they interject commentary at (in)appropriate moments. The parrot seems to have been trained by some unknown force to shriek and contort itself in objection to Mrs Merdle’s pontifications and invocations of Society as the be-all and end-all of human existence. These objections seem more pointed and direct than the “malevolent gaze[s]” (Ch 13) and seemingly irrelevant comments of Mr F’s Aunt. Yet I’ve often wondered if, with careful and intensive study, Mr F’s Aunt’s comments might not prove to be spot on – ???.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I’d argue that Maggy is kind of like that (interjecting seemingly crazy things that are really meaningful.) The way she speaks of the hospital as some kind of paradise is funny, but it also underlines how hard life is for the poor: living in a hospital is like a dream come true for them. And by urging Little Dorrit to tell Arthur Clennam the story of the princess and the secret, she comes close to revealing to him the truth that her “little mother” is concealing from him.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gosh, Chris…SO many marvelous ideas to consider here. I love that you consider the parrot and Mr F’s Aunt (a favorite!) in light of Grip!

And your assessment of the original title, Nobody’s Fault, is brilliant. I was thinking of that line–jumping ahead here–from A Tale of Two Cities:

“Altogether, the Old Bailey, at that date, was a choice illustration of the precept, that ‘Whatever is is right;’ an aphorism that would be as final as it is lazy, did it not include the troublesome consequence, that nothing that ever was, was wrong.”

In different forms (the “justice” system, the Circumlocution Office, Chancery, etc), Dickens always criticizes the notion that no one takes responsibility. (Again, that issue of responsibility vs irresponsibility–e.g. Skimpole!–that we discussed in Bleak House.) A kind of societal version of that spiritual “heresy”–if you will–of quietism. A passivity, rather than an active goodness and justice. It’s no one’s fault, that’s just how the world works! (Though there is a kind of flip side to this, as though Dickens is saying that the true version of this is a kind of hair’s breadth away. Because in ATTC there is also the sense of the inevitability of *consequences* of actions–or inaction–and that “all things have come together as they have fallen out”; or, “it could not be otherwise”.)

What is curious to me is why this also relates to Arthur personally. I love what Dickens does–at the same time, I wonder what he is implying by this, and how Arthur kind of takes on the persona of “Nobody.” Perhaps it is a kind of inevitable result of a repressive upbringing. In a way–without giving spoilers–might we also say that Mrs Clennam has dodged certain responsibilities of *truth* and *reparation* all her life? She says that her whole life is one of reparation…but in reality, she is dodging the responsibility of fessing up. And Arthur’s long (wasted?) service of the family business abroad is the result, and the corresponding lack of self-worth, the depression. At the same time, he goes out of his way to take on and rectify the wrongs and failed responsibilities of others.

On another note…I love the love for Amy Dorrit here in the comments this past week & more! I agree that she is one of Dickens’s most complex, heroic, and beautiful characters, and as Lenny says, far more complex than Nell. (A matured young lady; a matured author?) I absolutely love her fairy tale that she tells Maggy — and as Chris commented earlier (in our first weeks), there is that wonderful line of hers, “I could never have been of any use, if I had not pretended a little.” That, in her imagination, she is free of the prison around her; her capacity to think more unconventionally, more imaginatively, more compassionately, sets her apart.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“I absolutely love her fairy tale that she tells Maggy — and as Chris commented earlier (in our first weeks), there is that wonderful line of hers, ‘I could never have been of any use, if I had not pretended a little.’ That, in her imagination, she is free of the prison around her; her capacity to think more unconventionally, more imaginatively, more compassionately, sets her apart.”

Like Sissy Jupe?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Chris, thank you for this on ‘Nobody.’ I’ve been puzzling and puzzling this over. It really helps.

LikeLike

I’d like to hearken back to Chapter 13 to ask a question I forgot to ask before. Could it be that Mr. Casby knows that reintroducing Flora to Clennam will shatter the man’s romantic memories and does so partly out of sadism? I wouldn’t put it past the man.

In Hard Times, Dickens portrays strolling players very positively and in Nicholas Nickleby, he mocks actors with affection, so it’s interesting to read him taking a negative, satirical view of artistic types in Chapter 26 with his description of the resentful bohemians.

You’ve got to love these descriptions of Lord Lancaster Stiltstalking!

“This noble Refrigerator had iced several European courts in his time, and had done it with such complete success that the very name of Englishman yet struck cold to the stomachs of foreigners who had the distinguished honour of remembering him at a distance of a quarter of a century.

He was now in retirement, and hence (in a ponderous white cravat, like a stiff snow-drift) was so obliging as to shade the dinner. There was a whisper of the pervading Bohemian character in the nomadic nature of the service and its curious races of plates and dishes; but the noble Refrigerator, infinitely better than plate or porcelain, made it superb. He shaded the dinner, cooled the wines, chilled the gravy, and blighted the vegetables.”

This description of the lady who “who must have had something real about her or she could not have existed, but it was certainly not her hair or her teeth or her figure or her complexion” reminds me of Mrs. Skewton from Dombey and Son.

It’s interesting that Arthur Clennam speaks of “beginning the world anew” just like Richard Carstone.

In a reply to another comment, I mentioned that modern readers are probably more likely to agree with Miss Wade and Tattycoram on some issues more than with Arthur Clennam and Mr. Meagles. I was mainly thinking of Tattycoram’s assertion that Mr. and Mrs. Meagles have no right to name her as if she were a cat or a dog and Miss Wade’s accusation that her “droll name” singles her out and separates her from the rest of the family. But while Dickens undeniably sides with Meagles on the whole, I can’t help but wonder if it’s not just our modern biases talking, and he wants us to seriously consider the accusations on some level. After all, in other books, Dickens condemned self-righteous do-gooders, like Mrs. Pardiggle of Bleak House and Sir Joseph Bowley in The Chimes, who claimed to be helping the poor while patronizing and dehumanizing them. Of Course, the Meagles family are much more genuinely helpful to Tattycoram than those characters are to those they “help.” But aren’t their attitudes a bit similar? And could Dickens really have not noticed that or meant us to notice it?

While I think Dickens does a great job of making us feel sad for Arthur Clennam in his unrequited love for Pet Meagles, we don’t feel as sad as we might since we’re not particularly invested in her at first and we can guess that Clennam is meant for Little Dorrit. But in Chapter 28, Pet grows more interesting as she reveals her conflicting loyalties to her family and to her suitor. Interestingly, she kind of echoes Tattycoram’s complaints that she doesn’t really deserve her place of privilege in her parents’ hearts. (“Yes, I know; but all homes are not left with such a blank in them as there will be in mine when I am gone. Not that there is any scarcity of far better and more endearing and more accomplished girls than I am; not that I am much, but that they have made so much of me!”) Could it be that, like Tattycoram, she’s sick of her life and wants to rebel? Marrying against her parents’ wishes could be a way for her to assert her independence. Her expressed goal of reconciling her future husband and her father reminds me of David Copperfield’s intentions of molding his first wife’s mind or Richard Carstone’s belief that he’ll be able to resolve the Jarndyce suit if he just focuses all energy on it. Good luck with that!

In Chapter 29, we see a rare softer side to Mrs. Clennam as she interacts with Little Dorrit. Or is it a guilty side?

During Rigaud’s interview with Mrs. Clennam, we see the cowed and terrified Affery rebel just a little bit against her employer, when she says that whatever is unnerving her, “ain’t me. It’s him!”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Stationmaster, I AM one of those modern readers who sympathizes with Miss Wade and Tattycoram. They represent for me–in at least this point in the narrative–outliers who seem to be sort of “placeless” in this novel. Tatty is taken in by the Meagles to do laborious tasks for Pet and the family, but who really represents a kind of nobody in the parlance of the novel. And she becomes resentful of her lowly position. As you point out, the name the family “gives” her defines her degradation and her minimal worth in their lives. On top of this more personal level, I believe she represents, also, a symbol in the novel, a symbol of the ways in which the more fortunate people and families in the England of the 1820’s treated their help. The name which they chose for her speaks 1000’s! And it speaks also for the poor in THIS novel who right in front of us are living out lives of wretched poverty. Bleeding Heart Yard is definitely one of those impoverished locales.

Keep in mind that…

…during his early journey to America, Dickens was appalled by the way people of color were treated by both the northern and southern aristocrats in the States, seeing how they were demeaned by their “owners” relationships to them and the abject poverty that defined their physical lives. I’m wondering if his portrait of Tatty, here, is a kind of carryover of his anger at and frustration with the slavery and its dehumanization (which Stationmaster speaks of) which he saw during his trip….

And is not Miss Wade a kind of spokesperson for this authorial anger and frustration?

As I have noted earlier, Miss Wade is not afraid to speak her mind, with intelligence and clarity. In her own harsh manner, she helps define for us the ways in which Tatty is being “used” by the family. But she’s a kind of voice in the wilderness in this novel, and I’m not so sure she has the moral and physical heft to make the headway with her thoughts and actions that social change requires. I want her to succeed, I want her to find happiness in her life and to do her best for Tatty–yet, I don’t know how the novel (and the society it illustrates, therein) will allow this positive, quite feminist desire to happen in a fruitful manner.

Ultimately…

The question then, is, will the novel restore to Tattycoram her real name–Harriet Beadle! That, in itself, would be a symbolic gesture!!!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Well, FWIW, I’m not sure how “laborious” Tattycoram’s tasks would be. I’m not an expert but I think an “attendant” would just have to help her mistress dress and undress, pack her suitcase, maybe do some dusting, etc. You can definitely see how Tattycoram would grow to resent Pet though. Dickens never really offers a counterargument to her complaint that there’s no reason Pet should be loved and cherished and not herself. She’s sort of trapped between two worlds, not really one of the servants, not really one of the family either.

It’s also worth that noting “Harriet Beadle” was also a name bestowed on Tattycoram by the powers that be so I’m not sure if her reclaiming it counts as much of a triumph.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Such a fantastic conversation between Lenny & Stationmaster here! I see both points…and as Stationmaster says, even the name “Harriet Beadle” was a public bestowal, much like Oliver Twist’s name, bestowed by Mr Bumble when his own list of poor workhouse children’s names reached that letter…

Yes, Tatty/Harriet seems to be more in the position, in terms of her relation to Pet, as a paid companion…not laborious tasks necessarily, but we might say that the Meagles haven’t really done full justice to her. They meant well…but can we imagine having a biological child (Pet) and an adopted child (Harriet), and treating them differently? They should be loved the same and treated like their own.

And perhaps this also reflects the position of women in Victorian society in general too; couldn’t we say that “Pet” too is a kind of “pet name”? (I confess I do love nicknames, but for the sake of argument here…)

So, I do think there is a lot of justified anger here with these women; ultimately, I think their anger at the position of women in society in general is absolutely justified, even if the specific targets of their anger is somewhat misapplied. I won’t say more, but there is one character that Miss Wade is **very understandably and justly** angry with, but it has had the effect of her perhaps misconstruing (or, at least, putting the worst possible light on) everyone else’s motivations too. Is her anger justified? I really think so. To whom should it be directed? Hmmm…that’s the tougher one. That elusive “Nobody” keeps springing up…so many deflecting responsibility, that even justified anger becomes diffuse, occasionally misdirected.

LikeLiked by 2 people

There’s an interesting moment in Chapter 22 where Arthur Clennam is bothered by the idea of Little Dorrit loving John Chivery since it doesn’t fit in with his exalted image of her and then chides himself that there’s nothing really wrong with that.

Chapter 31 shows Mr. Dorrit at his most elastic. In a short space of time, he goes from being a big baby because his younger daughter was treating Old Nandy as an equal to being at his most aloof and “patriarchal” (I know Dickens applies that term to Casby, not Dorrit, but it fits here) as he presides over the meal. Maybe he’s desperately trying to compensate for his humiliation. The scene with Tip is both hilarious and mortifying as we imagine what it must have been like for Little Dorrit to be in the room. The best touch is probably Mr. Dorrit seeming like he’s going to reprimand his son for acting as if Clennam owes them money whenever they ask, only for him to actually reprimand him for not giving Clennam the benefit of the doubt and seeing if he does give them money in the future. The fact that Tip gives Little Dorrit an apology albeit a brief, unconvincing one contributes to the touch of decency in his character.

It feels like everyone is getting friend zoned in the first half of Little Dorrit, Flora by Clennam, Clennam by Pet, John Chivery by Little Dorrit and Little Dorrit by Clennam (though in her case, it’s more like daughter zoned.) You could even say that Edmund Sparkler has been friend zoned by Fanny.

Chapter 33 is one of my favorites. I love the satirical conversation between Mrs. Gowan and Mrs. Merdle and Mr. Merdle’s surprising emotional outburst in the more dramatic scene that follows.