Wherein your co-hosts of The Dickens Chronological Reading Club 2022-24 (#DickensClub) introduce our twenty-fourth read–and Dickens’s final completed novel–Our Mutual Friend.

(Banner Image: By James Mahoney.)

Friends, in nearing the end of our chronological reading journey together, do we, like Mr Lorry in A Tale of Two Cities, “travel in the circle, nearer and nearer to the beginning”? Light and shadow, wealth and poverty, life and death…all are here, imaged above all in the River itself. The eternal River haunts us again here, as it haunted little Paul Dombey’s thoughts as he imagined it wending its way to the Sea.

There is so much to discuss, and we hope that you will join us! First, a few quick links:

- Historical Context

- Thematic Considerations

- A Note on the Illustrations

- Reading Schedule

- Additional References & Adaptations

- General Mems for the #DickensClub

- A Look-Ahead to Weeks One and Two of Great Expectations

- Works Cited

Historical Context – Dickens’s Life in 1864 and 1865

“Our Mutual Friend offers us his last look at London, the London of the 1860s, ‘a black shrill city, combining the qualities of a smoky house and a scolding wife; such a gritty city, such a hopeless city, with no rent in the leaden canopy of its sky.’ A city too in which people starve to death in the streets every week; and in which the middle classes are shown as corrupt, complacent, lazy, greedy and dishonest, more interested in the pursuit of shares than the pursuit of love … You take away with you the river, tidal, dark and powerful, the cheerless townscapes of London, the skies, the clocks striking through the night, the littered streets and gritty London churchyards, a whole physical world.” — Claire Tomalin

Charles Dickens was entering the autumn of his life. He would live for only six years more, his death hastened by over-work and the stress of his (very lucrative) public readings. Already his family and friends were beginning to drop off. In the introduction to Great Expectations we discussed how his London literary circle had fractured; now, in the span of a few years, he lost Augustus Egg, his mother-in-law, his own mother, William Thackeray, and his son Walter. The loss of his immediate family seems to have troubled him less than the loss of his fellow writers: the death of Catherine’s mother, of whom he was not fond, seems to have come as a relief, while there’s no indication that he reacted to the loss of Elizabeth Dickens with the same grief that had attended the death of his father, John, in 1851. Walter, who died of an aneurysm in India, had been estranged from Dickens for several months as a result of poor decisions and growing debt—debt that became Dickens’s own when the boy died. In a letter dated shortly after the news reached him, Dickens wrote, in an echo of Jacob Marley, “I carry through life as long and as heavy a chain of dependents as ever was borne by one working man.” In fact, it was the loss of John Leech on 29 October 1864—Leech, who had memorably illustrated the scene of Marley meeting Scrooge in his chambers—that affected him the most. Slater tells us that he was “shocked and distressed,” remembering Leech’s special fondness for his son Sydney, the “Little Admiral.” Dickens confided to Forster that the news of Leech’s death upset him so much that for two days he could do nothing.

Ackroyd, with his usual atmospheric flair and interest in Dickens’s unexpressed interior life, tries to reconstruct how this period, these losses, might have affected him:

“The summer of 1863 was as unsettled as the spring. He went back once more to France in August, but had returned to Gad’s Hill Place by the end of the month, with two projects now firmly on his mind; one was the Christmas issue of All the Year Round, the writing of which had become part of his settled routine, and the other was the novel which he had been contemplating for at least the previous two years. Now, at last, he thought he was ready to begin; he wrote to Chapman and Hall in order to fix the appropriate terms for what would be his first long novel for seven years; he wanted six thousand pounds for half the copyright, and he got it. He was so eager to begin that nothing really could stop him, not even the deaths of those around him. He had once said that to live through middle-age was to walk through a kind of cemetery, and so it was to prove in this last half of the year … He was already ‘closely occupied’ upon his narrative when there were more deaths. Thackeray died suddenly on the Christmas Eve of that year. One might invoke here Dickens’s words to William Edrupt on the ending of one of his stories, ‘… they all die sooner or later.’ Augustus Egg dead. His mother dead. Now Thackeray. They all die in the end. Dickens attended Thackeray’s funeral and as he stood at the graveyard he ‘… had a look of bereavement in his face which was indescribable. When all others had turned aside from the grave he still stood there, as if rooted to the spot, watching with almost haggard eyes every spadeful of dust that was thrown upon it. Walking away with some friends, he began to talk, but presently in some sentence his voice quivered a little, and shaking hands all round rapidly he went off alone.’ Was he thinking also of his own death as he watched the dirt being thrown upon the novelist’s coffin?”

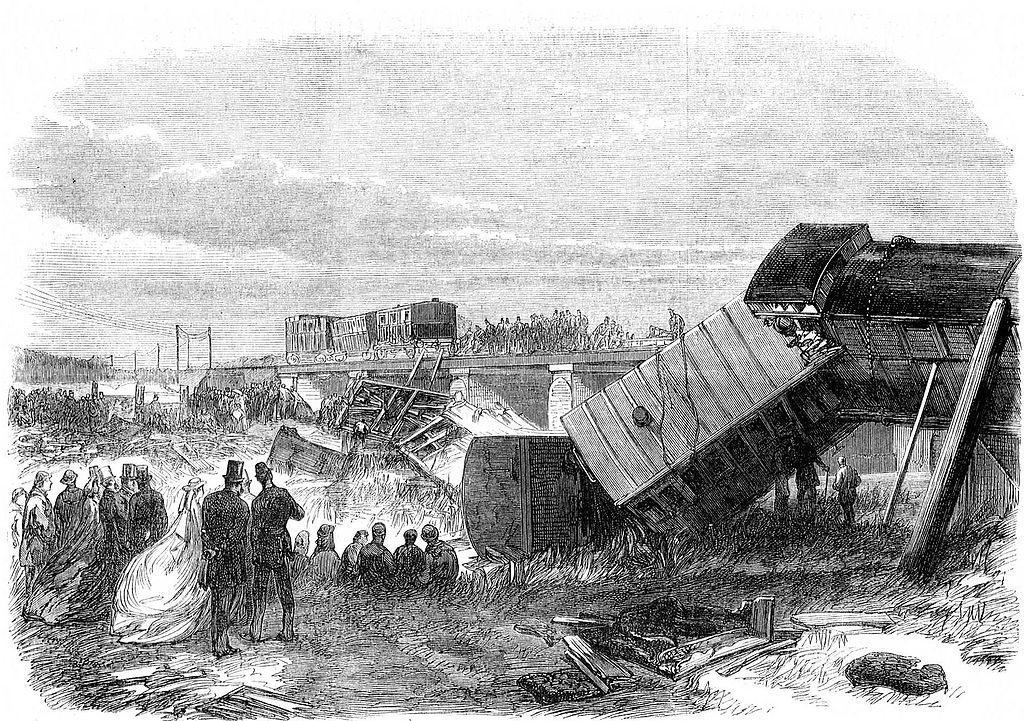

If he wasn’t already thinking of his own death, subsequent events would shortly bring it to the fore. On 09 June, 1865, Dickens was traveling by train from Folkestone in the company of Ellen Ternan and her mother when, through a series of errors on the part of the foreman and others involved in maintaining the railway, the train derailed over the Beult Viaduct, with part of it hanging suspended in midair. Ten people died and forty were injured. At the moment of the crash, Ellen said to her companions, “Let us join hands, and die friends,” which more than one biographer has taken to suggest that she and Dickens had been quarreling. (Several members of Dickens’s family would later claim that he had fathered a child with Ellen, and Claire Tomalin has marshaled evidence that it may have been born during the period just before Dickens began writing Our Mutual Friend, when he was traveling frequently from England to France.)

In any event, Dickens behaved heroically in the aftermath, persuading two of the guards to yield up their keys (“Look at me,” he said; “do stop an instant and look at me, and tell me whether you don’t know me”), which he used to open one of the carriages and lead the trapped passengers to safety. He then tended to the wounded and dying, providing them water, and, incredibly, when he realized that he had left the manuscript for the forthcoming number of Our Mutual Friend in his coat pocket, climbed back into the suspended train and retrieved it. Dickens seldom behaved more nobly, though the memory of the event continued to trouble him; from then on he found traveling difficult, and, perhaps not coincidentally, he would die five years to the day after the crash.

A window into Dickens’s creative process is given by an incident during this period in which he mentioned to Marcus Stone, his new illustrator, that he wanted to introduce some “peculiar avocation” into the story that would be “striking and unusual.” Dickens had a well-honed habit of inventing surreal and evocative setpieces that would imprint themselves on the reader’s brain—see, for example, the coffin-maker’s shop in Oliver Twist and the waxworks in The Old Curiosity Shop. Stone, as it transpired, knew just the place.

Slater takes up the story:

“Stone had been in need of someone to supply and ‘set up’ (that is, kill, stuff and fix into a certain pose) for him either a little dog or some pigeons (Stone’s memory varied as to which poor creatures were involved) and had just visited a picturesque taxidermist’s shop in St Andrew’s Street, Seven Dials. He described it to Dickens who must have been delighted with this piece of serendipity since the raw materials of taxidermy (bones, feathers, body parts, and so forth) fitted in so perfectly with his great dust-heap theme—as well as providing a role for Wegg’s lost leg. Next day, Dickens accompanied Stone to the shop and ‘with his usually keen power of observation, was enabled during a very brief space to take mental notes of every detail that presented itself,’ which he was then able to reproduce as Mr Venus’s shop in the last chapter of Our Mutual Friend II. Mr Venus himself seems to have been inspired by the taxidermist’s assistant, ‘a despondent melancholy youth.’”

Perhaps the most surprising thing here is that a taxidermist’s shop hadn’t already found its way into a Dickens novel. One is struck, too, by the keenness of Dickens’s observational powers, the way he could instantly scan a room and make a mental note of everything in it. He had demonstrated this gift in Sketches by Boz in the description of the marine store with its “armour and cabinets, rags and bones, fenders and street-door knockers, fire-irons, wearing-apparel and bedding,” pickle bottles, corner cupboards, wine-glasses, a flute, a curling iron, and the gift had never deserted him, even now in middle age when he feared, without reason, that his powers were waning. During the two years between the writing of Great Expectations and this book he suspected—those around him must have suspected—that he had passed his creative peak. So the writing of Our Mutual Friend, once it began in earnest, proved immensely satisfying, because it showed Dickens in full possession of his faculties, writing in top form—strange, savage, lurid, hilarious, impassioned and angry by turns, not an ounce of him diminished. He remained the Inimitable.

On a happier note, it was during this period that Dickens received probably the best gift he was ever given. Charles Fechter, an up-and-coming actor who had recently made a sensation playing Hamlet and Victor Hugo’s Ruy Blas before taking over management of the Lyceum Theatre, called on Dickens at Gad’s Hill in January 1865. There he gave Dickens a box containing the ninety-four pieces needed to assemble—of all things—a Swiss chalet. Slater tells us, “The delighted Dickens had it erected on the piece of land called the shrubbery that he owned on the opposite side of the road from Gad’s Hill itself (he later had a tunnel dug beneath the road so that he could reach the chalet more conveniently),” and the chalet became his favorite writing spot during the warmer months. It was here that Dickens was working on the middle portion of Edwin Drood five years later when he suffered the stroke that would claim his life.

Thematic Considerations

“Money—money, money…”

“Go in for money, my love. Money’s the article.”

Earning it, stealing it, inheriting it, losing it, blackmailing for it. Money is indeed the article in Dickens’s last completed novel, and some of the themes revolve around this topic: the dangers of having it and loving it too much; the dangers of putting it before love; the tragedy of not having it, but the true worth of those who lack it. Its power to give “tradesmen” a place in Society; the worth—or lack of it—of that very Society. We read of a fortune to be made in literal “dust mounds,” and we might ask: is money, after all, worth any more than “dust,” in the end?

Our Mutual Friend as a “Women’s Novel”?

Arguably, Our Mutual Friend has three—or five, if we count a couple of secondary characters such as the spirited, workhouse-hating Betty Higden or the warm Mrs Boffin—of Dickens’s finest female creations: Lizzie Hexam, whose father was a boatman who made his living along the filthy river; Bella Wilfer, headstrong and money-loving and utterly honest; and Miss Jenny Wren, the disabled “dolls’ dressmaker” who must provide for a drunken father and who befriends Lizzie in her hour of need. We would be hard-pressed to find three stronger and more distinct female heroines in the Dickens canon. Lizzie represents all that is good and “womanly” in Dickens—the faithful daughter and sister, the homemaker—but has the strength of will to go against the wishes of those she cares for, when they go against her sense of right and self-worth. Michael Slater calls Lizzie “a latter-day Gothic heroine glowing like a jewel in a dark setting” (Slater 521).

Dickens, Disability, and Subverted Expectations

As we have discussed earlier in our chronological journey—and as Dr Christian Lehmann has discussed in regard to Mr Dick in David Copperfield—Dickens had a gift for representing people of such various interests, abilities, and positions. He appears to have been particularly adept at representing those with either physical or intellectual/developmental disabilities, from Mr Dick and Smike, to Barnaby Rudge, and making them as fully a part of the action and emotional resonance with the reader as anyone else in his novels, if not more so. Here, Dickens gives us not only a heroine with a physical disability, Miss Jenny Wren, whose “back is bad and her legs are queer,” but the delightful “Sloppy,” who appears to have what we might now call an intellectual or developmental disability.

But we want to put Jenny in the spotlight for a moment: Jenny is not only a witty, snappy-tongued, eccentric character with the strength to make an unusual and difficult living for herself and her alcoholic and unreliable parent, but she becomes something of a conduit for comfort and connection to a higher plane. One of our leading characters wishes to speak to her on what he believes may be his deathbed, as Jenny seems connected mysteriously to the angels—not because she is artificially angelic herself, as many Dickensian heroines are accused of being, but perhaps because she retains that unique guilelessness of childhood—though she has always needed to be the “adult” in the situation from a young age. For a marvelous tribute to this unique character, check out Sara Schotland’s article in Disability Studies Quarterly, “Who’s That in Charge? It’s Jenny Wren, ‘The Person of the House.’”

Dickens even subverts our expectations for Dickensian tropes. In his final novel, he has cast off and tried to make reparation for his own antisemitic portrayal of Jews in Oliver Twist, with a paternal and saintly figure in Jenny’s friend, Mr Riah, who assists her and Lizzie in their trials. When Eugene mocks Riah, it is one of Eugene’s least attractive moments. As with Pancks vis-a-vis Casby in Little Dorrit, we find that the underling in the case (Riah) is really the innocent one vis-a-vis his disgusting “Christian” master, Fledgeby, the man behind the curtain. Here again, there is the overturning of Society’s prejudices, expectations, and biases. Dickens has effectively “cast down the mighty from their thrones and has raised up the lowly” (Lk 1:52).

For more on antisemitism in Dickens, and the change that took place between Oliver Twist and Our Mutual Friend, see Boze’s wonderful essay from early on in our chronological journey.

Our Mutual Friend as a “Problem Novel”?

Putting out a brief note for consideration here, while trying not to give spoilers:

We have one of the most delightful heroines, Bella Wilfer, charming us by her blunt honesty and self-appraisal of her love of money. Sure, we know there must be an arc coming for her; but how does it come, and are we comfortable with it when it does? The mysterious character of John Harmon, with his several aliases, plays a role in it all—and what do we make of this role? Are we venturing into The Taming of the Shrew territory here? Is there too much testing, and too little honesty and trust?

The River: Life and Death

“The real protagonist…is the river…the genius of the author ebbs and flows with the disappearance and reappearance of the Thames.”

~Algernon Charles Swinburne

Three characters die in the river. Three others in the novel are nearly drowned and are recalled to life. One family and one “rogue” make their living by it—in part by stealing from corpses.

“How can you be so thankless to your best friend [the river], Lizzie? The very fire that warmed you when you were a babby was picked out of the river alongside the coal barges. The very basket that you slept in the tide washed ashore. The very rockers that I put it upon to make a cradle of it I cut out of a piece of wood that drifted from some ship to another.” Dickens is the master at bringing everything—characters, places, themes/motifs—full circle, and this novel represents the height of his mastery in this. The river is the beginning and the end, the Alpha and Omega of London and of life, just as the river leading to the sea was an image of life leading towards death in Dombey and Son.

A Note on the Illustrations

As if to underscore the changes in Dickens’s life during this season of transition, he parted ways with Hablot K. Browne, AKA “Phiz,” who had been illustrating his books for some thirty years. No satisfactory explanation was ever given—Phiz himself seems to have taken the rejection personally—though there had been a marked falling off in the quality of his work that must have been apparent to anyone reading A Tale of Two Cities. Dickens began casting around for a replacement and settled on Marcus Stone, no one’s idea of a genius, but a member of the younger generation of illustrators who imbued the story with a sense of newness and vigor befitting an author eager to assert his continuing relevance. “If there are times when Stone’s drawings anticipate the illustrations in the Strand magazine at the end of the century,” notes Ackroyd, “there are also occasions in Our Mutual Friend when the conversation of Eugene Wrayburn might have come from a drama by Oscar Wilde.” One can’t help but wonder what Dickens might have written had he lived into the 1870s, ‘80s or ‘90s; it’s hard to imagine aught but death extinguishing the spark of genius in him.

Reading Schedule*

*note: We will read Our Mutual Friend over the course of 8 weeks (followed by a longer 4-week break, due to Boze & Rach’s wedding!), with a summary and discussion wrap-up every other week. It was published in monthly installments and is divided into four “books,” so we will use those books as our 2-week divisions

| Week/Dates | Chapters | Notes |

| Weeks 1 & 2: 28 May to 10 June, 2024 | Book the First: The Cup and the Lip, Chapters 1-17 | Our portion during the first two weeks was published in monthly installments (I-V) between May and September, 1864. |

| Weeks 3 & 4: 11-24 June, 2024 | Book the Second: Birds of a Feather, Chapters 1-16 | Our portion during Weeks 3 & 4 was published in monthly parts (installments VI-X) between October 1864 and February 1865. |

| Weeks 5 & 6: 25 June to 8 July, 2024 | Book the Third: A Long Lane, Chapters 1-17 | Our portion during Weeks 5 & 6 was published in monthly parts (installments XI-XV) between March and July, 1865. |

| Weeks 7 & 8: 9-22 July, 2024 | Book the Fourth: A Turning, Chapters 1-17 | Our portion during Weeks 7 & 8 was published in monthly installments (XVI-XX, the final being a double number) between August and November, 1865. |

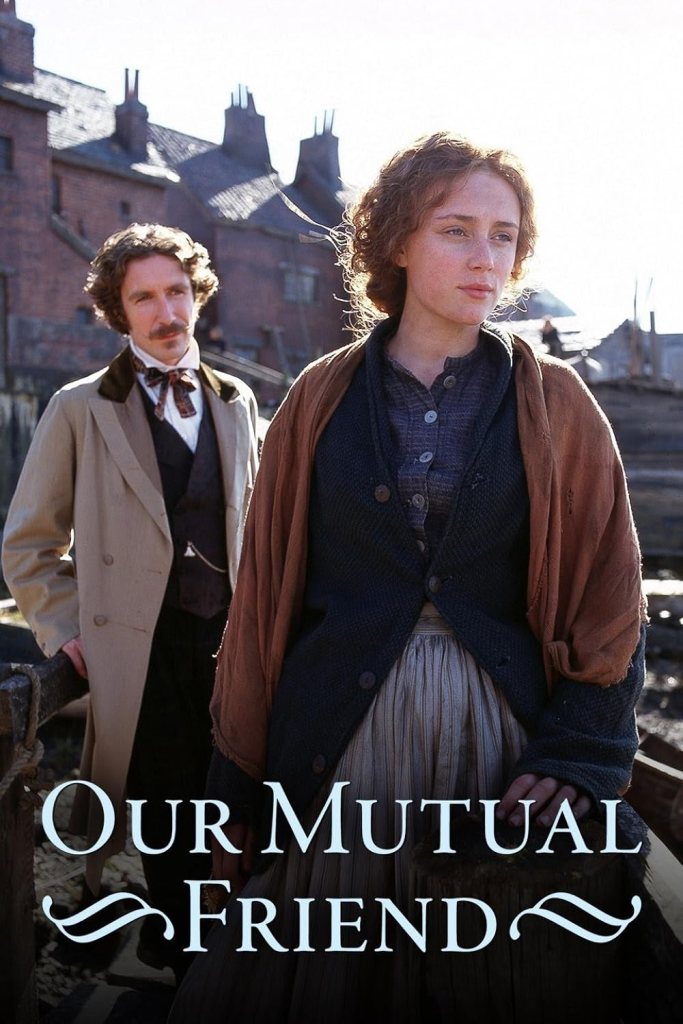

Additional References and Adaptations

Our Mutual Friend has been adapted for BBC television three times, in 1958, in 1976, and, most memorably, in 1998. The latter, featuring Keeley Hawes, David Morrisey, David Bradley and Paul McGann, is one of the great literary adaptations, leisurely and atmospheric. It’s worth noting that the novel features in LOST—Desmond Hume (one of our favorite characters) is given a copy by his girlfriend, Penny, which he reads while stranded in a hatch on a mysterious island. It becomes his favorite novel. He later names a boat Our Mutual Friend.

Paul McCartney, a lifelong Dickens fan—he cites Nicholas Nickleby as his favorite novel—wrote a song about Jenny Wren, entitled simply “Jenny Wren,” on his acclaimed 2005 album Chaos and Creation in the Backyard.

For the audiophiles among us, there are several options to choose from. Currently, your co-hosts are loving the narration by stage and screen actor David Troughton, who, as it happens, played Sloppy in the 1976 screen adaptation! (We have yet to see it.)

General Mems for the #DickensClub

SAVE THE DATE (and let us know which works for you):

First of all, a huge “thank you” to all who joined in for our Zoom chat on Great Expectations! And a huge “thank you” to those who have been reading the optional essay collection, The Uncommercial Traveller! For our Zoom chat on Our Mutual Friend, we’re looking at either Sat, Aug 10 or Sat, Aug 17th, 2024.

If you’re counting, today is Day 876 (and week 126) in our #DickensClub! This week and next, we’ll be beginning Our Mutual Friend, our twenty-fourth read as the group. Please feel free to comment below this post for the first and second weeks’ chapters or use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter.

No matter where you’re at in the reading process, a huge “thank you” for reading along with us. Heartfelt thanks to our dear Dickens Fellowship, The Dickens Society, and the Charles Dickens Letters Project for retweets, and to all those liking, sharing, and encouraging our Club, including Gina Dalfonzo, Dr. Christian Lehmann and Dr. Pete Orford. Huge “thank you” also to The Circumlocution Office (on twitter also!) for providing such a marvellous online resource for us. And for any more recent members or for those who might be interested in joining: the revised two-and-a-half year reading schedule can be found here. If you’ve been reading along with us but aren’t yet on the Member List, we would love to add you! Please feel free to message Rach here on the site, or on twitter.

A Look-Ahead to Weeks One and Two of Our Mutual Friend (28 May to 10 June, 2024)

This week and next, we’ll be reading Book the First: The Cup and the Lip, Chapters 1-17 of Our Mutual Friend. Our portion during the first two weeks was published in monthly installments (I-V) between May and September, 1864.

Feel free to comment below for your thoughts this week and next, or use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter.

If you’d like to read it online, you can find it at a number of sites such as Gutenberg.

Works Cited

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens. New York: HarperCollins, 1990.

Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

Tomalin, Claire. Charles Dickens: A Life. Penguin: New York, 2012.

This is another Dickens book that I’ve never read before, but I do know the broad story since I saw the 1998 miniseries and read a short retelling for children in The Usborne Complete Dickens. I did try to read the actual book first, but I couldn’t get into it. I am looking forward to reading the whole thing now though I don’t think it’s going to be my favorite. I mean, I could from those adaptations that it has a great story, but I personally wouldn’t say it’s as great a story as A Tale of Two Cities or Great Expectations. But who knows? Maybe I’ll completely adore it by the end.

From the adaptations I sampled, it struck me that this story has an unusually high number of characters for Dickens that we’re not sure whether they’re good guys or bad guys until the end. I think that might be why I’m not expecting it to be my favorite since it means less time to get attached to any that turn out to be good. But since that’s one of the things that makes the story suspenseful and exciting, I can’t really say I wish Dickens hadn’t done it that way. And, hey, maybe that impression I got was totally inaccurate to the experience of reading Our Mutual Friend. We’ll see.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Greetings, Fellow Inimitables!

Like Stationmaster, I am setting about reading this work for the first time, having my appetite whetted by this introduction and the 1998 miniseries.

Blessings of a wonderful journey with “Our Mutual Friend”!

Daniel

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry about the weird bullets and numbers. It didn’t “translate” well from a Word document to here!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I thought it worked wonderfully! Such great points and quotes!

And I’m thrilled that this is the first time with OMF for several of our members: Daniel, the Stationmaster, and Boze! This is the one Dickens novel that Boze had not previously read. How exciting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I finished the reading for these two weeks! Since this is my first time reading the book, I probably won’t have as many thoughts as I’ll accumulate on subsequent readings. Sorry about that.

Chapter 1 is very effective in its creepiness. I love the way Lizzie Hexam pulling up her hood symbolizes her shame over what her father is doing. Chapter 2 kind of made me wish I was reading an edition of the book with footnotes though. It seems unusually full of cultural references with which I’m not familiar. (All Dickens’s books contain references modern readers won’t understand of course, but that chapter seems like it has more of them than the other chapters.) Maybe that’s why I couldn’t get into the book before.

A long time ago, I wrote that Dolly Varden of Barnaby Rudge was atypical for a Dickensian lady. She wasn’t as pure and saintly as, say, Rose Maylie, Agnes Wickfield, Amy Dorrit or Lucie Manette but she wasn’t a creepy antiheroine like Edith Dombey, Louisa Gradgrind or Estella either. She reminds me more of such Dickensian antiheroes as David Copperfield, Richard Carstone and Pip: flawed but in a relatable, human way. I wondered if Bella Wilfer, whose book I hadn’t read yet, could be described in similar terms. So far, she could go either way. It’s hard to think of her as being like Dolly Varden who was chipper and playful and whose initial fault was being a bit of a callous flirt. Bella is harsh and angry, almost like a stereotypical emo teen. There’s something of Estella’s bluntness in the way she shamelessly proclaims her love of money. But she’s much more like a regular person than Estella and, while she doesn’t handle it very maturely, it does feel she got the short of the stick in her situation. (Then again, you could argue that Edith, Louisa and Estella were also dealt bad hands by life.) She shows that she’s not a completely terrible person in that, unlike her haughty mother, she accepts the Boffins’ kindness gratefully. Or could that just be more mercenariness?

Lizzie Hexam is much more of a typical Dickens heroine, most notably in her painful relationship with her father. That’s not to say she’s a bad character! In fact, the conversation between her and Charley in Chapter 3 is one of the most well written in the book so far, I think. And Dickens does some interesting things with her. I’d expect her reaction to being told about the accusations against her father would be horror but instead she laughs, which I think does a better job of establishing that she doesn’t believe them. I’d also expect her to maintain her faith in his innocence but interestingly she has doubts later in the chapter. Technically, I think Lizzie is a great character but because I’ve been following along with this group’s reading for so long, I can’t help but be less interested in her and her relationship with her father since Dickens has covered so many similar heroines with similar relationships.

I enjoy Mortimer Lightwood and Eugene Wrayburn’s sarcasm. They kind of remind me of Harthouse from Hard Times. (You could say Eugene turns out to be what Harthouse pretends to be.)

Could Dickens have meant us to sympathize with Rogue Riderhood a little bit or is he just supposed to be creepy? In his last novel, Dickens sympathetically presented a character against whom others were prejudiced because he’d been a convict. It’s interesting to read the scenes of Riderhood being ostracized with that in mind.

It’s too bad there are no illustrations for Chapter 7. So much of the humor is visual with everybody else being freaked out by Mr. Venus’s profession and he himself being totally accustomed to it.

Podsnap is an amusing Dickensian bore and I’m loving Abbey Potterson and her schoolmarmish relationship with her customers. (I picture her as being played by Jane Kaczmarek.) But so far, Our Mutual Friend’s supporting characters aren’t endearing themselves to me as much as those in the books Dickens had written not so long before this one. (I also feel like the prose isn’t as engaging for whatever reason.) They seem to me like less interesting versions of characters from other Dickens books. (Mr. Inspector of Inspector Bucket, the Boffins of the Meagleses, etc. The satire of high society recalls Dombey and Son and Little Dorrit. And the indictment of workhouses as Betty Higden gives could have been from practically any Dickens book.)

What really frustrates me is that I’ve read seventeen chapters and most of them were just about setting up the numerous subplots. After the exciting opening situation, it felt to me like the plot stalled and only picked up in Chapter 12. After the nimbleness of A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations, this was somewhat disappointing. I’m loving the main characters, but we’ve seen so little of them so far. Bella Wilfer, the one I find most interesting, has only appeared in three chapters, I think! Oh well. I was getting really into the story right before I finished the assigned reading so I’m hoping this was just a rocky start.

P.S.

Does anyone else find themselves accidentally thinking of Rogue Riderhood by the name of Red Riding Hood? LOL.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Rach & Boze for (as usual!) a lively and thorough intro to this amazing book!

I’m enjoying listening to the David Troughton Audiobook, too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, everyone, for such marvelous insights! I think we are all feeling the oncoming of summer, and the busy-ness that sometimes comes around this time–I just finished out with the kids in Skills class at the high school, had graduation, family visiting, sewing deadlines since early May, etc–but I have been keeping up in the reading, and I will just make a few notes, for now:

I absolutely LOVE the atmosphere in this novel. The River/Limehouse depiction, especially.

I love that the Rokesmith character is a bit darker and more mysterious in the book than I have seen him portrayed onscreen.

Eugene is on the “Sydney Carton” spectrum, but at the far end–if Sydney were more cynical, more careless of *others* rather than only careless of himself. He’s like a Sydney gone to seed.

LOVE the women, Bella and Lizzie. I agree with Stationmaster that sometimes Lizzie’s responses are untypical for our Dickensian heroines, and Bella is delightfully flawed and charmingly honest.

More anon! Looking forward to our next section…

LikeLike