Wherein your co-hosts of The Dickens Chronological Reading Club 2022-24 introduce our twenty-fifth and final read together: The Mystery of Edwin Drood, Dickens’s last, unfinished novel.

It is the stuff of a gothic, genre mystery. Opium addiction. Envy. A double life. Obsessive love… or lust. Jealous rivals. Possible murder weapons. A young man gone missing, and possibly murdered. Possible locations for the crime, and for the body. Quicklime. A missing ring.

But we don’t have a body. Is the missing man dead or alive? And who the Dickens is Dick Datchery? Is he a new character, or one of our already-known characters in disguise?

These and many other questions have haunted Droodists and Dickensians for decades.

How would Dickens have finished his final, half-completed novel? It’s our turn to be the detective, a Dick Datchery…

But first, a few quick links:

- Historical Context

- Thematic Considerations & Enigmas

- A Note on the Illustrations

- Reading Schedule

- Additional References & Adaptations

- General Mems for the #DickensClub

- A Look-Ahead to Week One of The Mystery of Edwin Drood

- Works Cited

Historical Context – Dickens’s Life at the Time

“Drood has to be seen in three ways. First, as the unfinished mystery which has received extraordinary attention just because it is a puzzle left by Dickens and offers itself for ingenious speculation by those who enjoy thinking up solutions. Secondly, as half a novel … which has divided opinion sharply even among Dickens’s warmest admirers, from Chesterton’s hailing it as the creation of a dying magician making ‘his last splendid and staggering appearance’ to Gissing’s and Shaw’s dismissal of it as trivial and of no account. And thirdly, as the achievement of a man who is dying and refusing to die, who would not allow illness and failing powers to keep him from exerting his imagination, or to prevent him from writing: and as such it is an astonishing and heroic enterprise.”

— Claire Tomalin

Charles Dickens was getting older. He had passed fifty-five, and in the final years of the 1860s his health continued to wane. Lingering troubles with his foot made it difficult to climb stairs. He suffered from hemorrhaging and occasionally found that he only recognized the right halves of words. After his death, loved ones recalled a moment when he struggled to say the word Pickwick, pronouncing it “Pickswick” and “Pecksnick.” Privately they worried for him, and began to imagine what had once previously seemed unthinkable—that the great pen might one day be stilled. That Charles Dickens might come to an end.

Dickens himself was taking precautions. Shortly after his fifty-eighth birthday he wrote a letter to Macready congratulating him on turning 77—this in an age when men were lucky to reach sixty. It’s clear from his letters, and from certain passages in Drood, that his thoughts were turning towards the next world. During a trip to London in May 1869 with American friends Annie and James Fields he visited the settings of some of his more famous books—“the room where Pip had lived in Great Expectations, the dark staircase on which Magwitch had stumbled and the narrow street where Pip had found lodgings for his unwanted benefactor,” Peter Ackroyd tells us, “Dickens pointing out these dwellings as if his characters had been real.” On the following day, 12 May, he drafted a new will.

The fates of his children weighed on him, more so than ever. He had only recently rescued Charley from insurmountable debt by inviting him onto the staff of Household Words. Sydney had incurred so many debts that Dickens, in an unguarded moment, voiced a wish that he were dead. Charles Collins, elder brother of Wilkie and husband of Kate Dickens, was in poor health and would soon die of stomach cancer. Dickens made it known that he regretted Kate having married Charles, which badly stung Wilkie and led to a cooling off in their friendship (not helped by Dickens calling The Moonstone “wearisome beyond endurance”).

Not all his children were failures. Says Slater, “Frank was doing well in the Bengal Mounted Police, as was Alfred, working as a land agent in Australia, while Henry was beginning to distinguish himself academically” at Trinity Hall, Cambridge—the only one of his seven sons to attend university. But by and large they were not a promising bunch. Just how much Dickens was concerned with their fates—their success or, in most cases, failure—is clear from two memorable incidents at this period. One was the departure of Plorn—ineffectual but beloved—for Australia, a trip that his father had organized on the suspicion that Plorn would not fare well in England. (Plorn’s life in the Outback is the subject of a recent novel, The Dickens Boy, by Thomas Keneally, the author of Schindler’s List.) When the time came for Plorn to board the train at Paddington Station that would take him away forever, Henry later recalled that the normally reserved Dickens was overcome. “My father,” he wrote, “openly gave way to his intense grief quite regardless of his surroundings … I never saw a man so completely overcome.” Several days later Dickens was heard to say, “I find myself constantly thinking of Plorn.”

The second incident involved Henry himself, who so distinguished himself at Cambridge that he was awarded an annual stipend of fifty pounds. (“Henry,” Ackroyd reminds us, “was the only one of his children to have achieved any success in life”). Years later, Henry would write of the moment when he shared the good news with his father:

I knew that this success, slight as it was, would give him intense pleasure, so I went to meet him at Higham Station upon his arrival from London to tell him of it. As he got out of the train I told him the news. He said, ‘Capital! capital!’ – nothing more. Disappointed to find that he received the news apparently so lightly, I took my seat beside him in the pony carriage he was driving. Nothing more happened until we had got half-way to Gad’s Hill, when he broke down completely. Turning towards me with tears in his eyes and giving me a warm grip of the hand, he said, ‘God bless you, my boy; God bless you!’ That pressure of the hand I can feel now as distinctly as I felt it then, and it will remain as strong and real until the day of my death.

In the years after the publication of Our Mutual Friend Dickens continued to work vigorously. During the summers he worked from Monday to Thursday of each week in London, managing All the Year Round, while on the weekends he returned to Gad’s Hill. But already he was planning a new novel and “in the autumn,” Slater tells us, “a six-month farewell series of one hundred readings, for which the Chappells would pay him eight thousand pounds plus all expenses…” The highlight of this public tour, which led him all over England and destroyed what remained of his health, was a dramatic reading of the murder of Nancy in Oliver Twist. Forster and friends attempted to dissuade Dickens from embarking on this lucrative venture because they feared, rightly in retrospect, that Dickens was driving himself into an early grave. As he took the stage each night, says Slater, he was not only killing Nancy—he was killing himself.

Dickens and Ellen Ternan no longer seem to have lived together, but she continued to accompany him to his readings to the last. There are some hints in Edwin Drood which biographers have seized on to suggest that their relationship was now more akin to that of a brother and sister. Whatever the case, in the early months of 1870 Dickens stayed often at Tyburnia, overlooking Hyde Park: he told his reading manager, Dolby, that he enjoyed hearing the noise of the waggons each morning at dawn as they made their way from Paddington to the central markets. In the late spring he returned to Gad’s Hill Place, where he wrote the final chapters of Edwin Drood—the final words he would ever write—and enjoyed a series of visits with his children that are haunting for what they reveal about the nervous strain he was under, and the weight of regrets. (One can’t help but think, in this respect, of Johnny Cash—another beloved entertainer who told stories of desperate souls leading unvarnished lives, who in his final years trailed a cloud of exhaustion and despair, who held his success lightly, who wondered whether fame had been worth it.)

Ackroyd picks up the tale—it is one of the most devastating scenes in the annals of Dickens:

That night he stayed at the office, unusually for him, and on the following morning his son, Charley, found him working there on The Mystery of Edwin Drood. He was about to leave for the day and went in to see his father, who was still ‘writing very earnestly.’ After a moment ‘I said, “If you don’t want anything more, sir, I shall be off now,” but he continued writing with the same intensity as before, and gave no sign of being aware of my presence. Again I spoke—louder, perhaps, this time—and he raised his head and looked at me long and fixedly. But I soon found that, although his eyes were bent upon me and he seemed to be looking at me earnestly, he did not see me, and that he was, in fact, unconscious for the moment of my very existence. He was in dreamland with Edwin Drood, and I left him—for the last time.’ There is something very disturbing about this anecdote, the prematurely aged man still so immersed in his images and words that he could not even see his own son standing in front of him. And what of Charley himself? In retrospect he must have been disturbed, too. This was the last time he would ever see his father, and yet he was ignored by him in favor of the creatures of his imagination.”

A few days later he had his last encounter with any of his children—with his daughter, Kate:

He seemed to improve during dinner and then, afterwards, he smoked his usual cigar and took a stroll in the garden with both his daughters, the air filled with the sweet scent of syringa shrubs. Afterwards he sat in the dining room and contemplated his new conservatory, which had just been completed as an extension to that room. Mamie had gone into the drawing room to play the piano, and Dickens listened to her solitary music as he sat looking at the flowers. Kate had mentioned to her father that she wanted to talk to him about a decision she was about to make—she wanted to go on the stage, in order to earn some money for herself and her ailing husband—and at eleven o’clock, when Georgina and Mamie had retired to bed, and the lights in the conservatory had been turned down, father and daughter talked together. They discussed her plans, of which Dickens disapproved since there were people in the theatrical profession ‘who would make your hair stand on end.’ They considered the matter for a while but then, when Kate rose to leave, Dickens asked her to stay because he had more to say to her. He talked of his hopes for The Mystery of Edwin Drood, ‘if, please God, I live to finish it.’ Then, he added, ‘I say if, because you know, my dear child, I have not been strong lately.’ He went on to talk of the past but not of the future, and it seemed to his daughter that ‘he spoke as though his life were over and there was nothing left.’ Then he went on to regret that he had not been ‘a better father—a better man.’ Kate said, in a later unpublished account, that he also mentioned Ellen Ternan. Father and daughter did not leave each other until three in the morning.”

Regretted that he had not been a better man. There is a world of weariness and desolation in those words.

The way he was speaking must have spooked Kate. On the following morning Dickens went into the chalet to write, and she, knowing how much he hated being disturbed, asked Georgina to send him her love. But then, whilst waiting on the porch for the carriage, she thought better of it. Seized, as she later wrote, with “an uncontrollable desire to see him once again,” she ran through the tunnel to the chalet. On previous occasions Dickens, immersed in his book, had merely offered his cheek to be kissed. But on this morning he glanced up eagerly and then, in an unprecedented gesture, took her into his arms and held her close.

It was the last time they would see one another. Four days later he was suddenly taken ill during dinner with Georgina and asked to be lowered to the floor. He fell into a coma from which he never recovered. Early on the following evening, with his family arriving from across London, he began to sob loudly. Fifteen minutes later he let out a heavy sigh, and a single tear, and passed from this world. Charles Dickens, the greatest novelist in the English language, was no more.

Thematic Considerations & Enigmas

Dickens’s “Writing Lab”: Tone & Atmosphere; Influence of Wilkie Collins; Dickens as Mystery Writer

“The real theme of the novel lies not in its complicated plot but rather, as Dickens’s daughter, Kate, has expressed it, in Dickens’s ‘wonderful observation of character,’ and his strange insight into the tragic secrets of the human heart.’”

— Peter Ackroyd

From Drood’s opium-dream opening, we realize that we’re not in Kansas anymore…nor even the Dickensian London that we know. Still, for all its strange, dark elements–the double-life of the choirmaster, the storm of Christmas Eve echoing the danger to come, the Gothic crypts of Cloisterham Cathedral–there is arguably a lighter narrative touch here than in, say, Bleak House or Our Mutual Friend. From the teasing relationship of Edwin and Rosa, to the eccentric Bazzard to the fresh & wholesome Tartar and Minor Canon Crisparkle, there is a kind of airiness to the narrative that might hearken back to some of Dickens’s earlier works.

As Drood followed on a success such as Collins’s The Moonstone, one wonders what influence, if any, Wilkie’s own detective story, full of the intrigue of other cultures, might have had on the Inimitable. Dickens was always a “mystery novelist,” in that there are always mysteries and secrets at the heart of all of his novels—Bleak House, Little Dorrit, and Great Expectations come especially to mind—but was Drood to be the beginning of what we might call a more “genre mystery” period in Dickens’s writing career? Or was he less interested in the “whodunnit” aspect, than in the psychology of a jealous addict and killer?

Contrasts: Light and Shadow, Life and Death

From Pickwickian sunshine to Droodian shade, this novel, suffused with a Gothic atmosphere, also strongly contrasts the light and shadow within its pages. The very name “Crisparkle” suggests shining, lightness, airiness; Jasper, by contrast, is all duplicity and obscurity and shade. From the light airiness of “the Nuns’ House” and Miss Twinkleton, to the darkness of the crypt and the intentions of one who wants to search its mysteries and, perhaps, use them for his own shadowy purposes.

Dickens as “The Haunted Man”: A Return to Rochester; Unfulfilled Loves; A Double Life

With Drood, we have truly come full circle in another sense: Dickens’s childhood and early memories of Rochester. Dickens never strayed far from his origins, and Rochester, which featured back during our travels with Pickwick, and which was one of the subjects of an essay in The Uncommercial Traveler, now is front and center (under the pseudonym “Cloisterham”) for Dickens’s final, unfinished novel.

During this period, Dickens himself might be said to be leading a double life, providing for and visiting Ellen Ternan and her mother–often under the name of John Tringham. And if there is one thing abundantly clear in a novel full of unsolved mysteries, it is that Dickens is fascinated by the double life of John Jasper, opium-addict and ostensibly the respectable choirmaster of Cloisterham Cathedral. In Jasper’s obsessive, hopeless love/lust, do we see echoes of Dickens’s own frustrated life, and loves?

Obsession, Addiction, & Mental Illness

Addiction now adds imaginative force to the obsession of John Jasper for Rosa Bud. Hasn’t “obsession” and “unrequited love” been a theme for many of our journeys with the Inimitable, especially recently? Note a scene later in our readalong which might echo that of Headstone’s proposal to Lizzie Hexam.

A “Fixed Attention”: Ways of “Seeing” One Another; Cultural Racism and Stereotyping; Mesmerism

Chris brought this up this “seeing” or “looking” as a theme that was striking her more and more as she dipped into Drood again. Daniel brought it up in relation to Our Mutual Friend–where everyone is observing one another: John observes Bella and Bella watches Mr Boffin; Riderhood watches Headstone as the latter watches Eugene and Lizze, etc.

Here, Jasper is often described as having a look of “fixed attention,” especially towards Rosa and Edwin. How many characters “watch” one another in this book? Just as John Harmon watched Bella from the secret double (or triple) life he was leading, so too do several characters watch one another here. When we meet the “stranger” who arrives in Cloisterham later in our read, “he” seems to be watching everyone, especially Jasper.

We also have instances of how one’s look or gaze has power over another, echoing Dickens’s own belief in and practice of mesmerism. Jasper has this effect upon Rosa, which resembles one of control, or being compelled; Neville and Helena have a kind of telepathic connection to one another, and Helena is described as having a very strong influence upon him, as well, which she seems to be able to control with a look.

And there is so much more to ponder about the Landless twins. (Helena is certainly one of the most fantastic Dickensian heroines in our opinion.) They are part of the enigma of the story. Orphans from Ceylon (Sri Lanka) who have suffered ill-treatment from a cruel father, and their relationship to our other characters one of the book’s many unsolved mysteries. Neville proves to be the scapegoat of the story due to his own “violent” temper (not unlike that of our beloved Nicholas Nickleby, especially when there is injustice to combat), and due to his “Un-English” complexion, as pompous, self-satisfied Sapsea never fails to point out. What are we to make of them both? Who would each have ended up with, romantically? Is Neville guilty or innocent? Would Dickens have proved them to be related to one of our central characters? Might either one of them have disguised his/herself as another character in the story?

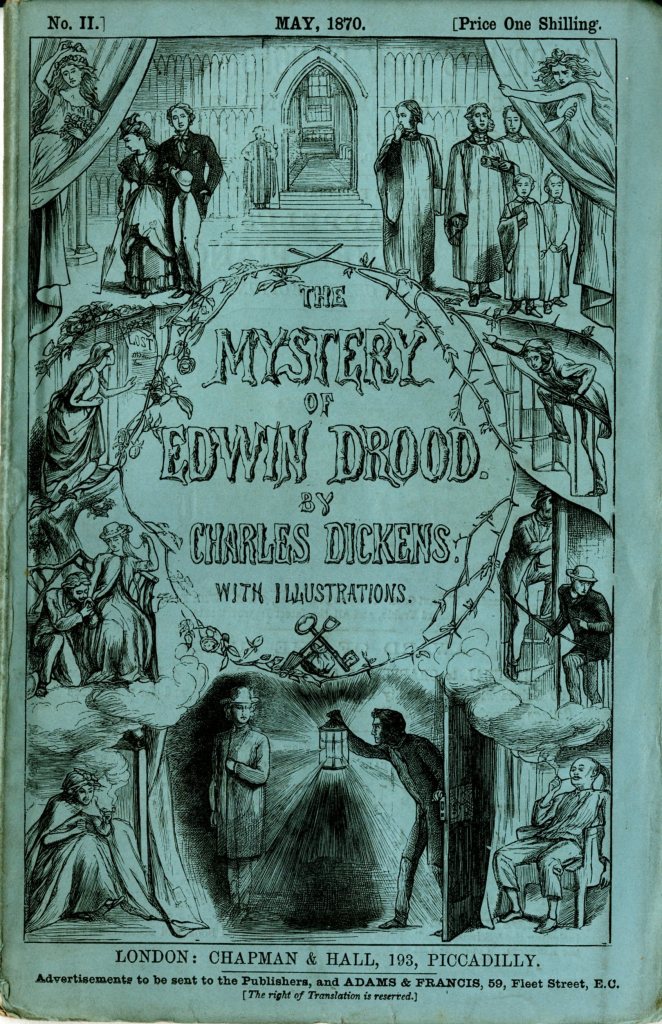

A Note on the Illustrations

Charles Collins, brother of Wilkie and husband of Dickens’s daughter Katey, began illustrations for The Mystery of Edwin Drood with its enigmatic wrapper which is supposed to contain–or does it?–several clues to the mystery. Due to Charles Collins’s poor health, the illustrations were taken over by Luke Fildes, an artist introduced to Dickens by the Pre-Raphaelite artist John Everett Millais. Fildes provided two illustrations for each of the published installments.

Reading Schedule*

*note: We will read The Mystery of Edwin Drood over the course of 6 weeks—one “installment” per week—with a summary and discussion wrap-up every week.

| Week/Dates | Chapters | Notes |

| Week 1: 20-26 August, 2024 | 1-4 | The first installment was published in April of 1870. |

| Week 2: 27 Aug to 2 Sept, 2024 | 5-9 | The second installment was published in May of 1870. |

| Week 3: 3-9 Sept, 2024 | 10-12 | The third installment was published in June of 1870. |

| Week 4: 10-16 Sept, 2024 | 13-16 | The fourth installment was published posthumously, in July of 1870. |

| Week 5: 17-23 Sept, 2024 | 17-20 | The fifth installment was published posthumously, in August of 1870. |

| Week 6: 24-30 Sept, 2024 | 21-23 | The sixth installment was published posthumously, in September of 1870. |

Additional References and Adaptations

Films have been made, novels written, and much critical ink spilled over the question of how the novel might have ended, with various solutions and resolutions proposed. Several authors have tried to complete the novel. Dan Simmons’s Drood takes a different spin, telling the story of Dickens’s final years from the perspective of friend/rival Wilkie Collins, in an almost Amadeus/Mozart-vs-Salieri like story. A book called The D Case brings in all of our beloved fictional detectives, from Sherlock Holmes to Hercule Poirot to Father Brown, in order to solve it. Dr Pete Orford (University of Buckingham) not only has a wonderful book on the subject, but he led readers from all walks of life in a detective hunt to solve it with The Drood Inquiry. G.K. Chesterton was involved in a court case set up by the Dickens Fellowship to “try” the fictional John Jasper for murder. A popular stage musical gets the audience involved in solving the mystery.

On film, we have a 1935 adaptation with Claude Rains as John Jasper. In 1993, Robert Powell took the role. Both are hard to find on streaming now.

If you have BritBox, you can witness a wonderfully atmospheric 2012 BBC adaptation with a frighteningly brooding Matthew Rhys as Jasper, a marvellous (as always) Alun Armstrong as Grewgious, gorgeous and intelligent Amber Rose Revah as Helena, and a scene-stealing David Dawson as Bazzard/Datchery. Whether or not the ending that they construct is likely to have been Dickens’s solution, it is certainly a clever one.

General Mems for the #DickensClub

SAVE THE DATE: Our final Zoom chat in our Dickens Chronological Reading Club will take place on 5 October, 2024! 11am Pacific (US) / 2pm Eastern (US) / 7pm GMT (London). Email Rach if you’re not on our ongoing Zoom link list and would like to join in!

If you’re counting, today is Day 960 (and week 138) in our #DickensClub! This week we’ll be starting The Mystery of Edwin Drood, Dickens’s final, unfinished novel, and our twenty-fifth and final read as a group. Please feel free to comment below this post for the first weeks’ chapters, or use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter.

No matter where you’re at in the reading process, a huge “thank you” for reading along with us. Heartfelt thanks to our dear Dickens Fellowship, The Dickens Society, and the Charles Dickens Letters Project for retweets, and to all those liking, sharing, and encouraging our Club, including Gina Dalfonzo, Dr. Christian Lehmann and Dr. Pete Orford. Huge “thank you” also to The Circumlocution Office (on twitter also!) for providing such a marvellous online resource for us. And for any more recent members or for those who might be interested in joining: the revised two-and-a-half year reading schedule can be found here. If you’ve been reading along with us but aren’t yet on the Member List, we would love to add you! Please feel free to message Rach here on the site, or on twitter.

A Look-Ahead to Week One of The Mystery of Edwin Drood (20-26 August, 2024)

This week, we’ll be reading the first installment of The Mystery of Edwin Drood, Chapters 1-4. This installment was published in April of 1870.

Feel free to comment below for your thoughts this week, or use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter.

If you’d like to read it online, you can find it at a number of sites such as Gutenberg.

Works Cited

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens. New York: HarperCollins, 1990.

Orford, Pete. The Mystery of Edwin Drood: Charles Dickens’ Unfinished Novel & Our Endless Attempts to End It. Barnsley: Pen and Sword History, 2018.

Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

Tomalin, Claire. Charles Dickens: A Life. Penguin: New York, 2012.

First of all, I LOVE this opening: “An ancient English Cathedral town [or “tower”, in some early editions]? How can the ancient English Cathedral town be here! The well-known massive grey square tower of its old Cathedral? How can that be here! There is no spike of rusty iron in the air, between the eye and it, from any point of the real prospect. What is the spike that intervenes, and who has set it up?” I love that “Cloisterham” is Rochester, filled with early memories for Dickens himself. We’ve come full circle.

This dark and yet whimsical opium dream sets the perfect “stage” for a drama that (I think) will surely have a lot to do, one way or another, with Jasper’s opium addition, and his strange way of seeing the world: Edwin…Rosa…himself. The ultimate sort of double-life here in Jasper; part “Wicked Man” with violent fantasies, and part respectable choirmaster. I wonder if some of the Dickensian characters that we’ve recently met have paved the way for John Jasper. Eugene’s weariness; Bradley Headstone’s dissatisfaction and watching?

We’ve seen enough of this sort of “watching” to be wary of Jasper’s attitude towards a supposedly beloved nephew, Edwin Drood: “Once for all, a look of intentness and intensity—a look of hungry, exacting, watchful, and yet devoted affection—is always, now and ever afterwards, on the Jasper face whenever the Jasper face is addressed in this [Edwin’s] direction. And when it is so addressed, it is never, on this occasion or on any other, dividedly addressed; it is always concentrated.” We also learn that Jasper’s life is a hell to him, that he is weary of his job and all connected with it—the very music that sounds so heavenly to others is “devilish” to him.

And what do we make of Edwin Drood himself? He seems pleasant enough at first glance, but also flippant and entitled, taking things for granted. Rosa is delightfully teasing, but in her particularly—and in them both—we sense the underlying dissatisfaction in their prolonged, expected engagement. And what is this hesitancy, almost fear, she has at Edwin’s mention of Jasper?

In the second chapter, we’re introduced to the Dean, the Verger, and of course the Minor Canon, Septimus Crisparkle. I think the latter’s opening inclined me to underrate him, and I love that Dickens does this. He’s lighthearted, mildly teasing (of Tope), with a stamp of a cheerful, “muscular Christianity”, “fair and rosy, and perpetually pitching himself head-foremost into all the deep running water in the surrounding country”—all of which makes us wonder whether he will be only a pleasant sidekick to the action. But there’s a lot more to him than meets the eye.

In Chapter Four, we meet the mayor, Thomas Sapsea, one of Dickens’s blustering and self-important public figures. How will the Sapsea tomb come into play? How will stonemason Durdles feature later, with his work amongst the Cathedral’s crypt, his keys, & his intimate knowledge of all things stony, relating to death?

LikeLiked by 2 people

p.s. Sorry for diving right into it on the first day…but of course, I’ve been living with Drood-related things for the last month or so, so I’m not wanting to get behind on the comments this time! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful intro, Roze! Haunting, that, the comparison of late Dickens to late Johnny Cash–I’m thinking of that stunning “Hurt” cover.

As for Drood, I’m hunting up a good audiobook version on either Audible or Everand.

LikeLiked by 1 person

YAY!!! Recommended so far: David Timson on Scibd/Everand!

LikeLike

Terrific introduction! Really terrific!

Just to expound upon my above-referenced “’seeing’ or ‘looking’ as a theme that was striking [me] more and more as [I] dipped into Drood again” – the issue of who is watching whom and how they are watching comes up often in Drood criticism. I’ve started really paying attention to this & am amazed at how, it seems, everybody is watching, everybody is being watched, it’s being done overtly and surreptitiously, people are watching other people watching people. We get some of their thought processes re the watching – why they are watching or why they think they are being watched, what they think of the person they are watching, what they think about the person watching them, what they think about the person watching someone else. People are also watching themselves – introspection of their behavior or the effects of somebody else’s behavior on them. It all feels so claustrophobic, which gives a new meaning to “Cloisterham”, the sense of being closed in or closed off, restricted or restrained, isolated.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much, Chris!! 💙 Boze’s sections were particularly moving & haunting, & he had me in tears last night, reading it aloud.

LOVE that take on the “claustrophobia”, and even a hint of that in the name “Cloisterham”!

LikeLike

Wonderful introduction! I’m looking forward to diving in to this final read of the DCRC with you all!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fr Matthew!!! YAAAAAY !!!🥳🥳🥳💙 We are so thrilled to have you aboard for this final adventure of the DCRC! 🕵️

LikeLiked by 1 person

As expected, John Jasper is an unusual main character for Dickens, being something of a villain protagonist. (Or so he seems at this point.) As Rachel said, he calls to mind Bradley Headstone with his brooding obsession. He also might suggest a male Rosa Dartle or Miss Havisham. Or maybe he’s an evil Sydney Carton. But, on the other hand, Dickens makes it clear he genuinely loves his nephew though he also resents him what with the whole love triangle thing. (I’m assuming at this point Jasper is besotted with Rosa Bud. Sorry if I’m jumping the gun there.)

I’m interested to learn more about the Dean. The descriptions of him in Chapter 2, mainly the way he’s “not unflattered by (Crisparkle’s) indirect homage,” make him seem a bit vain and a bit full of himself. But in Chapter 4, Dickens describes him as “a modest and worthy gentleman.”

Rosa Bud’s playful personality recalls Bella Wilfer. (Actually, she’s more like Dolly Varden from Barnaby Rudge but I’m making a point about chronology here.) It wasn’t so long ago that Dickens was celebrating quieter, more serious-minded young women. Remember how in David Copperfield, the responsible Agnes Wickfield proved the better wife than the frivolous Dora Spenlow. It seems like in his old age, Dickens valued liveliness more in women. (It’s worth noting that Agnes does tease David Copperfield from time to time but she’s never as witty as Bella or Rosa.)

Something else that recalls Our Mutual Friend is the nature of Edwin Drood and Rosa’s betrothal, how they’ve been pushed into it by their deceased parents. However, they don’t resent each other as much as John Harmon and Bella Wilfer (initially) do. They even enjoy flirting with each other a bit but it’s an awkward situation and eventually Rosa bursts “into real tears.” As she says, “I wish we could be friends! It’s because we can’t be friends that we try one another so.” I actually find this more interesting than the equivalent setup in Our Mutual Friend and I want to see where Dickens takes the relationship. Will Rosa decide she likes living in Egypt? Will Edwin get a different job for her sake? Will they break up and marry different love interests? (I do know what’s going to happen to Edwin eventually but I’m pretending I don’t know while I’m reading.) If only Dickens had finished the story!

So far, I’m enjoying the arrogant Mr. Sapsea more than the arrogant Mr. Podsnap. I love his ridiculous epitaph for his wife. In my copy of the book anyway, his own name “Mr. Thomas Sapsea” is in far bigger type than anything else. Speaking of his wife, when I was a kid, I read a book called The Fairy’s Mistake by Gail Carson Levin (which I highly recommend BTW), there was a fairy character called Ethelinda. I thought it was a made-up name for the fantasy setting. Apparently not. Who knew?

LikeLiked by 2 people

“There are some hints in Edwin Drood which biographers have seized on to suggest that (Dickens and Ternan’s) relationship was now more akin to that of a brother and sister. “

If it’s not too spoilery, could someone tell me what those hints are? Does the book have an unusual emphasis on platonic relationships as opposed to romantic relationships? I feel like most Dickens books are about both. This seems like a weird suggestion on the part of those biographers.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hi Stationmaster! Yes, I don’t want to spoil anything, so I’ll just say, we’ll be getting to that part in a couple of weeks, unless you’re reading ahead…I think this is particularly referring to Chapter 13! 🙂 Very interesting speculations as to Dickens, for sure.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The interaction between Edwin and Jasper in Ch 2 presents so many red flags about Jasper. The first is his room, “dark” and “sombre” and “mostly in shadow”. Though we are told the room “may have had its influence in forming his manner”, I think it more likely that his manner may have influenced the form of the room. Jasper is “a dark man”, not just in the coloring of his “hair and whisker”, but in his psyche. He is brooding and somber, secretive and mysterious.

The display of the unfinished portrait of Rosa is, in itself, not much until we are told that it is “hanging over the chimneypiece”, that is, it holds the position of prominence in Jasper’s room. This is troubling because Rosa is Edwin’s fiancee – she holds no relation to Jasper other than being his pupil. Perhaps the portrait is there because Edwin drew it and it is a good likeness. But it still seems a little odd that Jasper should display it where he does, especially when coupled with his “strange power of . . . including the sketch” in his “[f]ixed . . . look” at Edwin.

Jasper’s overly attentive attitude toward Edwin is odd, too. His “genial outburst of enthusiasm” is accompanied by “a look of intentness and intensity—a look of hungry, exacting, watchful, and yet devoted affection”. This look is “on the Jasper face whenever the Jasper face is addressed” towards Edwin. Note the wording: “THE Jasper face”, not “ON Jasper’s face” or “ON HIS face” – “THE Jasper face” seems to imply a thing apart from a human face, an entity separate from the two young men in this scene. Further, this look “is always, now and ever afterwards” present” and “it is never . . . dividedly addressed; it is always concentrated.” This is not a normal attitude of a normal loving uncle. It is the attitude of obsession, of disproportionate interest. The added “and yet devoted affection” is ambiguous. Is it a loving attachment to or fondness for Edwin, or does it denote an intensity of passion that is, for some reason, out of the ordinary?

One reason seems to rear its head when talk turns to Rosa, to Pussy. Is this not one of the most sexually tense scenes in Dickens? Jasper provides nut-crackers and crack go the walnuts every time Pussy is referred to. Edwin cracks three nuts to Jasper’s five, but Edwin “dips among his fragments of walnuts with an air of pique” once and plays with his nut-cracker twice. So, Jasper wields his cracker successfully whereas Edwin becomes aroused and plays with his implement. This seems a contest of machismo and Jasper appears to come out (ahem) ahead.

And then we learn Jasper’s big secret – he hates his life and his job. But I’m not sure this is the only secret Jasper means to impart. The more worrisome secret is that he is “troubled with some stray sort of ambition, aspiration, restlessness, dissatisfaction” which Edwin should indeed take as a warning. Unfortunately, Edwin exposes his vulnerability when he says “ I have no doubt that that unhealthy state of mind which you have so powerfully described is attended with some real suffering, and is hard to bear. But let me reassure you, Jack, as to the chances of its overcoming me. I don’t think I am in the way of it. In some few months less than another year, you know, I shall carry Pussy off from school as Mrs. Edwin Drood.” Jasper’s “expression of musing benevolence” at these words is again ambiguous – is he sympathetic with Edwin’s running headlong into an arranged marriage or is he pitying Edwin’s trusting cluelessness about his uncle’s underlying nature?

LikeLiked by 3 people

“He was simply and staunchly true to his duty alike in the large case and in the small. So all true souls ever are. So every true soul ever was, ever is, and ever will be. There is nothing little to the really great in spirit.”

― Charles Dickens, “The Mystery of Edwin Drood”

Greetings, Fellow Inimitables!

Here we go—our last Dickens read in this cycle. What a remarkable journey of learning, discovery, and enrichment we have been on!

It is, indeed, our turn to be the detective, the “Dick Datchery,” because this half-completed novel invites us to imagine how it might have turned out. (We have lots of clues in the portion Dickens wrote before his death.)

I was very touched by Dickens’ end-of-life remorse and regrets about not having been a better man, a better father. His inability to see his son due to the mental imaginings of “Drood” . . . truly the stuff of Shakespearean tragedy.

Given Chris’ rich reflections on this issue of seeing/gazing/looking/watching, I delighted in this: “We also have instances of how one’s look or gaze has power over another, echoing Dickens’s own belief in and practice of mesmerism.”

How multifaceted the human gaze! As my Jewish friends might say, it is all about kavanah (soul-level intention).

I was amazed to learn that “G.K. Chesterton was involved in a court case set up by the Dickens Fellowship to ‘try’ the fictional John Jasper for murder.” Amazing! Delightful! Positively Chestertonian!

Thanks for this wonderful introduction, a great foundation for reading Dickens’ last work—including your supplemental material, Chris. And, Adaptation Stationmaster, I always benefit from your musings–including how you compare similar characters from other novels. Thanks!

On the journey with you,

Daniel

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just a quick question/observation: For some reason, I never pondered in previous reads on this sentence in Chapter Two: “I have been taking opium for a pain–an agony–that sometimes overcomes me.” In my recollection, there is no physical pain focused on in regard to Jasper in any subsequent chapters, so this is very curious. Was it a physical, or purely psychological pain?

LikeLiked by 3 people

ALSO…for those listening on audiobook, Boze and I cannot recommend highly enough the version by David Timson. Timson also reads a lot of “introductions” to Dickens’s works, so I was curious enough to try, though I’d been used to another version read by David Thorn. (Though I love David Thorn’s voice and overall narration, his characterizations were bothering me…Jasper sounded too like a happy-go-lucky, down-to-earth Joe Gargery than a brooding, intelligent melancholiac. Other characterizations too sounded just a little *too* light, and Sapsea not pompous enough.) You can tell David Timson is an actor, because his characterization is absolutely masterful! Jasper is done in a voice close to his own, but with a cunning and melancholia that are just perfect for him. Sapsea is pretty hilarious, and absolutely spot on, IMO. Edwin is just great. Anyway, we haven’t gotten past this week’s reading portion yet in this particular version, but so far I am in ecstasies with it, especially with his Jasper. Highly recommended.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dickens seems to have faced his own “inner demons,” especially as he was nearing the end of his life.

My sense is that Jasper represents something of himself–a shadow self. Hence, the pain is likely more psychological than physical.

Thanks, Rach. That’s my two bits!!!

LikeLike