Wherein your co-hosts of The Dickens Chronological Reading Club 2022-24 (#DickensClub) wrap up Week 5 (Installment 5) of our twenty-fifth read, The Mystery of Edwin Drood; with a chapter summary and discussion wrap-up.

By the members of the #DickensClub, edited/compiled by Rach

“At about this time, a stranger appeared in Cloisterham…”

Friends, we had a shorter reading portion this past week, and we are now three chapters away from the end of the extant portion of this gem of a novel!

We’ve been introduced to two “new” (?) characters: Tartar, and Dick Datchery. But is Datchery really a new character? What do you think?

We’ve also discussed “philanthropy,” and have reveled in Crisparkle’s denunciation of Honeythunder.

So, let’s get cracking…

- General Mems

- The Mystery of Edwin Drood, Chapters 17-20 (Installment 5): A Summary

- Discussion Wrap-Up (Week 5)

- Questions, Theories, & Polls…

- A Look-Ahead to Week 6 of The Mystery of Edwin Drood (24-30 Sept, 2024)

General Mems

SAVE THE DATE: Our final Zoom chat of The Dickens Chronological Reading Club (#DickensClub) will focus on The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Join us on Saturday, 5 October, 2024! 11am Pacific (US) / 2pm Eastern (US) / 7pm GMT (London)! Email Rach if you’d like the link; she will send out the link via email the week of the Zoom chat.

If you’re counting, today is Day 994 (and week 143) in our #DickensClub! This week, we’ll be reading the sixth and final installment, or Chapters 21-23, of The Mystery of Edwin Drood, our twenty-fifth read as a group. Please feel free to comment below this post for the sixth week’s chapters or use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter.

For Boze & Rach’s “introduction” to Drood, including our reading schedule, please click here. For Chris’s supplement with additional resources for consideration, please click here.

No matter where you’re at in the reading process, a huge “thank you” for reading along with us. Heartfelt thanks to our dear Dickens Fellowship, The Dickens Society, and the Charles Dickens Letters Project for retweets, and to all those liking, sharing, and encouraging our Club, including Gina Dalfonzo, Dr. Christian Lehmann and Dr. Pete Orford. Huge “thank you” also to The Circumlocution Office (on twitter also!) for providing such a marvellous online resource for us. And for any more recent members or for those who might be interested in joining: the revised two-and-a-half year reading schedule can be found here. If you’ve been reading along with us but aren’t yet on the Member List, we would love to add you! Please feel free to message Rach here on the site, or on twitter.

The Mystery of Edwin Drood, Chapters 17-20 (Installment 5): A Summary

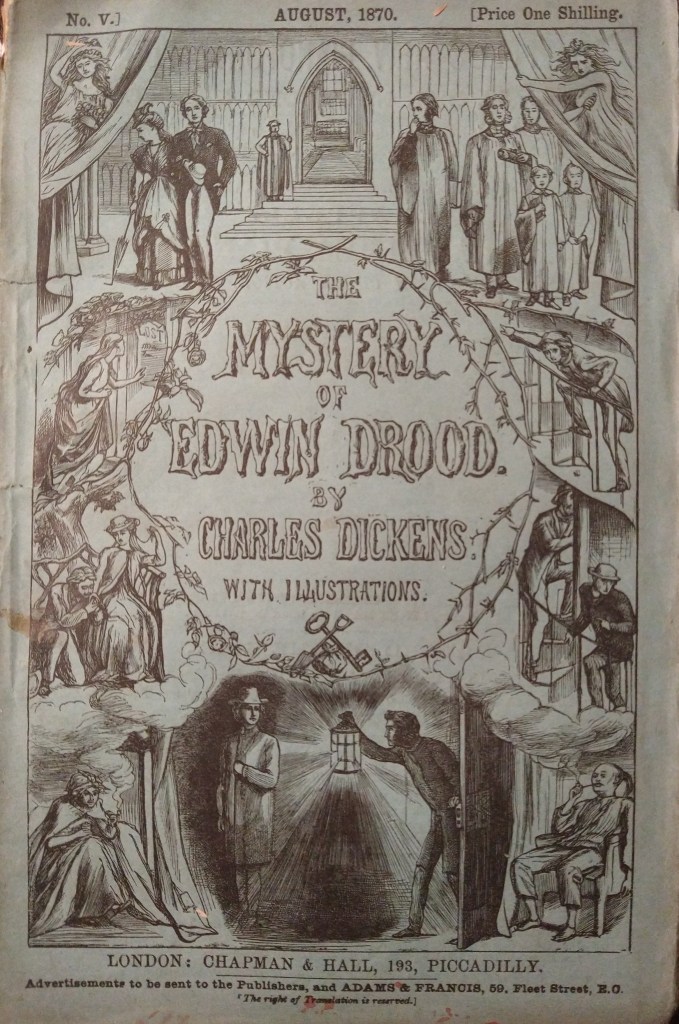

(Illustrated by Luke Fildes. Images below are from the Charles Dickens Illustrated Gallery.)

Six months later.

Crisparkle engages in a heated interchange with Mr Honeythunder, who assumes (without charity, nuance, or wisdom) that Crisparkle is defending a murderer, Neville. Crisparkle’s fearless retort and apologia are brilliant, clever statements of Dickensian philosophy.

Crisparkle visits Neville at his lodgings at Staple Inn. Neville has been assiduously studying, but is afraid of going out in daylight, because of all the gossip and looks. They speak of Helena, and how her mastery of herself and of her pride allows her to walk with respect through the streets of Cloisterham. Crisparkle then calls on Grewgious, who relates to him that John Jasper has been “slinking” nearby, in the shadows—they both see the man outside the window.

“I entertain a sort of fancy for having him under my eye tonight, do you know?”

As Nevile returns to his chambers after dining with Crisparkle, he meets one of his neighbors, the one who has beans, mignonette and wallflower growing at their back courtyard from his balcony. The handsome, sun-tanned man, near thirty, introduces himself as “Tartar,” and was a sailor in the Royal Navy—a First Lieutenant—until he came into an inheritance, the stipulation of which was that he quit his life at sea. This friendly man offers to extend his runners across their neighbouring balconies so that Neville can enjoy them closer at hand. With a quick farewell, Tartar returns to his flat through the back window “with a wave of his hand and the deftness of a cat,” making Neville giddy at his daredevil stunts.

“At about this time a stranger appeared in Cloisterham; a white-haired personage with black eyebrows.”

This stranger, a “single buffer” with “a military air,” stays at the Crozier inn, and puts himself forth as “an idle dog who lived upon his means.” He calls himself Dick Datchery. He wants more permanent lodgings; “something old…something odd and inconvenient and out of the way; something venerable, architectural, and inconvenient….Anything Cathedraly, now.” The waiter suggests that he speak to the Verger, Mr Tope.

On his way to meet with Tope, Datchery happens upon the boy Deputy who points out the lodging of Tope. Datchery is particularly interested when Deputy points out the lodgings of John Jasper, a man whom the boy is clearly frightened of. Datchery speaks to Jasper and Jasper’s friend, the Mayor; Datchery is almost theatrically respectful to that “potentate” Mr Sapsea, thereby making a good impression on him. When Jasper leaves, Datchery asks Sapsea about Jasper, and about the loss of his nephew. Sapsea then introduces Jasper not only to the epitaph on his dead wife’s monument, but to Durdles the stonemason. Datchery seems to be as interested in learning more about Durdles’s trade as Jasper was, and Durdles offers to show him. Datchery also makes clear to Deputy that, for the money he had previously given Deputy, the latter owes him a job, and states that he wants Deputy to show him to Durdles’s lodgings at such a time when it would be needful.

“Said Mr Datchery to himself that night, as he looked at his white hair in the gas-lighted looking-glass over the coffee-room chimneypiece at the Crozier, and shook it out: ‘For a single buffer, of an easy temper, living idly on his means, I have had a rather busy afternoon!’”

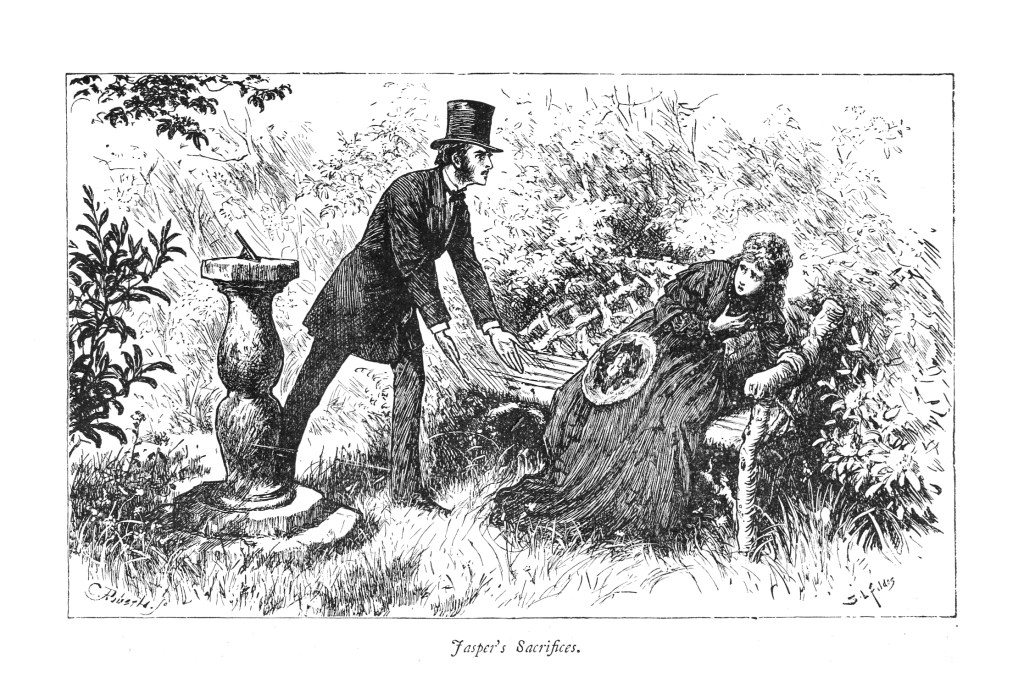

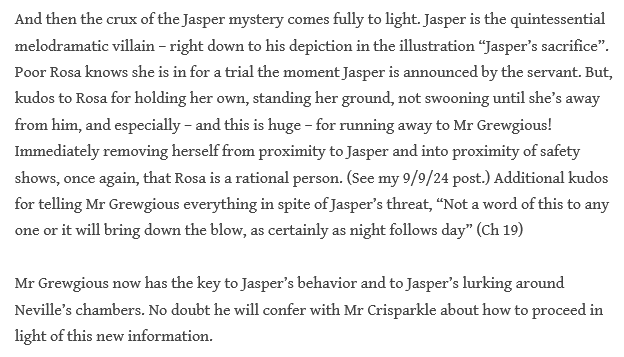

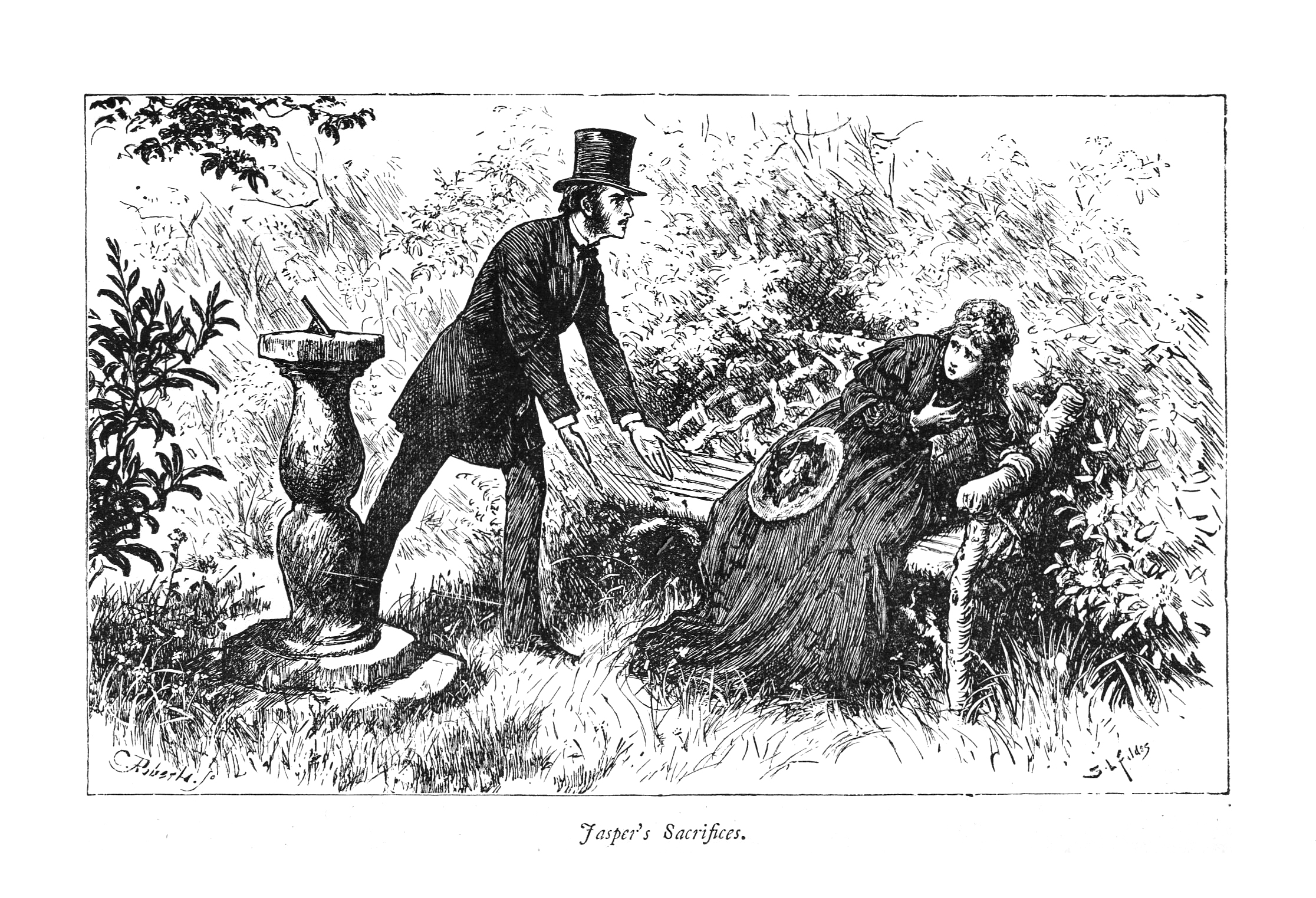

Rosa then has an unwelcome visitor at the Nuns’ House: John Jasper. Hating and fearing him, and knowing that those she would most wish to accompany her in meeting him are not at home, she agrees to meet with him in the garden, which is very visible from the windows, in case she should need to call out. Jasper possesses an almost mesmeric power over her. She says that she has given up her music lessons, not adding that this is because of her aversion to Jasper. He then says that he has something particular to communicate to her; when she at first refuses to hear him, he threatens her, and says that if she doesn’t, she will “do more harm to others than you can ever set right.”

“ ‘Dearest Rosa! Charming Rosa!’

She starts up again.

This time he does not touch her. But his face looks so wicked and menacing, as he stands leaning against the sun-dial—setting, as it were, his black mark upon the very face of day—that her flight is arrested by horror as she looks at him.”

He then confesses his “mad” love for her—a love that he felt through all of her engagement to Edwin Drood, and since. He confesses it all with such a violent look, that Rosa is horrified. She tells him so, and that he is “a bad, bad man,” the truth of which she couldn’t admit to Edwin because of his adoration of Jasper.

“How beautiful you are! You are more beautiful in anger than in repose. I don’t ask you for your love; give me yourself and your hatred; give me yourself and that pretty rage; give me yourself and that enchanting scorn; it will be enough for me.”

He again threatens her if she doesn’t hear him out. Threatens that he can do even more harm to Neville and his cause, and Helena’s good name. “Circumstances may accumulate so strongly even against an innocent man, that, directed, sharpened, and pointed, they may slay him.”

“I love you, love you, love you. If you were to cast me off now—but you will not—you would never be rid of me. No one should come between us. I would pursue you to the death.”

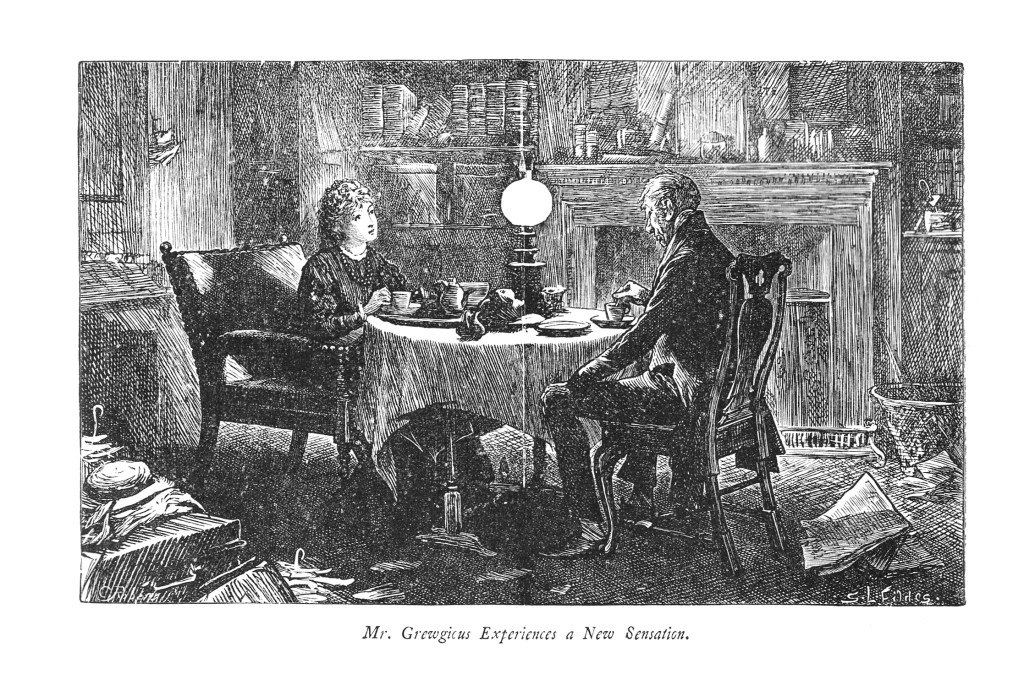

Later, Rosa’s determination is complete: “she must fly from this terrible man.” Alone and without a protector, Rosa flees to her guardian, Grewgious, at Staple Inn, London.

Grewgious, having been called to for refuge, is more than a match for the situation. With knightly gallantry, he accepts his charge as her protector utterly. “Damn him!” he says of Jasper. He finds her temporary lodging at Furnival’s Inn near his own, and is going to send for Miss Twinkleton to be her companion for the next month, after which they can decide their course in the time to follow. Grewgious also mentions that his clerk, Bazzard, is “off duty here, altogether, just at present,” and that he has a substitute employed until Bazzard’s return. They discuss Bazzard’s thwarted theatrical ambitions.

Discussion Wrap-Up (Week 5)

Miscellany & What We Loved

Daniel loved the wrap-up and all of the thoughts from last week. He adds:

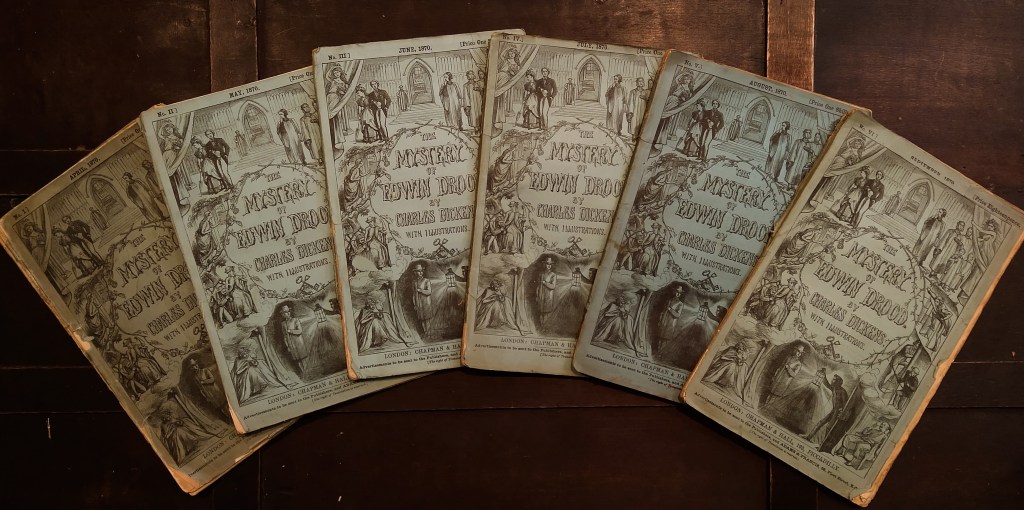

And Boze and I received the most surprising, thoughtful, treasured gift: a complete set of the first edition of The Mystery of Edwin Drood–all six installments!–from our friend & encourager Dr. Christian Lehmann. We were absolutely bowled over! Thank you so very much, Dr. Christian! What a way to celebrate the ending of this marvelous journey with Dickens:

Philanthropy & “Platform Manners” versus True Charity: Honeythunder versus Crisparkle

As Chris writes here, “Dickens has been railing against professional philanthropists and misplaced/misdirected philanthropy since Sketches by Boz,” and she comments here on Crisparkle’s wonderful defense and denunciation, and in his definition of true charity:

The Stationmaster loves the comparison of “Professing Philanthropists” to certain kinds of boxers:

“In his college days of athletic exercises, Mr. Crisparkle had known professors of the Noble Art of fisticuffs, and had attended two or three of their gloved gatherings. He had now an opportunity of observing that as to the phrenological formation of the backs of their heads, the Professing Philanthropists were uncommonly like the Pugilists. In the development of all those organs which constitute, or attend, a propensity to ‘pitch into’ your fellow-creatures, the Philanthropists were remarkably favoured…”

And the “platform manners” assumed by Honeythunder in this heated exchange with Crisparkle, which the latter denounces beautifully:

“You assume a great crime to have been committed by one whom I, acquainted with the attendant circumstances, and having numerous reasons on my side, devoutly believe to be innocent of it. Because I differ from you on that vital point, what is your platform resource? Instantly to turn upon me, charging that I have no sense of the enormity of the crime itself, but am its aider and abettor! So, another time—taking me as representing your opponent in other cases—you set up a platform credulity; a moved and seconded and carried-unanimously profession of faith in some ridiculous delusion or mischievous imposition. I decline to believe it, and you fall back upon your platform resource of proclaiming that I believe nothing; that because I will not bow down to a false God of your making, I deny the true God!”

The Stationmaster writes:

Rosa’s Flight

We were all cheering Rosa on, after the harrowing declaration by Jasper, for having the gumption and wisdom to flee immediately to Grewgious:

“Rosa might be the most rational of Dickens’s heroines,” as the Stationmaster writes:

“A Stranger Appeared in Cloisterham”: Dick Datchery

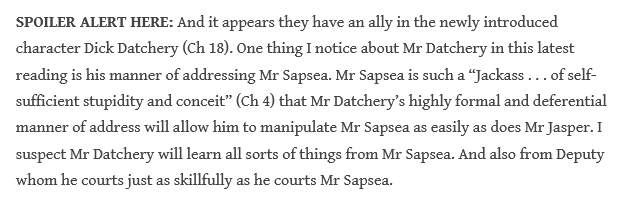

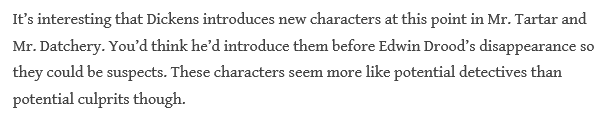

Here, we begin our discussion of one of the strangers we’ve encountered, the mysterious Dick Datchery. Chris writes:

And the Stationmaster comments in general about our new characters:

I too comment on Datchery, but I will save this for our next section, as some might prefer to wait on discussing Datchery’s identity until this coming week.

Questions, Theories, & Polls…

Last week, only two of us voted in the poll (as of Sunday morning) on the question of Helena’s match, and it was split between Drood and Crisparkle. Now, we have another consideration, but I will hold off on posting a poll until the final wrap up.

Who is Dick Datchery?

I write:

Chris responds with more fascinating evidence:

What do you think?

A Look-Ahead to Week 6 of The Mystery of Edwin Drood (24-30 Sept, 2024)

This week, we’ll be reading the sixth and final installment, Chapters 21-23, of The Mystery of Edwin Drood. This section was published in All the Year Round in September of 1870.

Please share your thoughts on this section in the comments below, or use the hashtag #DickensClub if commenting on Twitter/X.

If you’d like to read it online, it can be found at sites like Gutenberg.

I mistakenly thought Chapter 21 was part of last week’s reading. Here’s what I wrote about it in case anyone forgot.

“I’m certain now that Rosa was going to end up with Tartar by the end of the book. More than one man has been attracted to her so far, but the end of Chapter 21 is the first time she has ever been attracted to one of them. Of course, it’s possible Tartar was going to die by the end of the book or (less likely) turn out to be a villain or something like that. It’s so frustrating that we’ll never know!”

The happy excursion on the river in Chapter 22 makes for a nice change of pace from this book’s general darkness. So does the comedy of grumpy Miss Billickin and uptight Miss Twinkleton. At first, I felt that “the B” was all very well but no Miss Crump. However, she really grew on me as the chapter progressed and I love this bit about Miss Twinkleton.

Rosa soon made the discovery that Miss Twinkleton didn’t read fairly. She cut the love-scenes, interpolated passages in praise of female celibacy, and was guilty of other glaring pious frauds. As an instance in point, take the glowing passage: “Ever dearest and best adored,—said Edward, clasping the dear head to his breast, and drawing the silken hair through his caressing fingers, from which he suffered it to fall like golden rain,—ever dearest and best adored, let us fly from the unsympathetic world and the sterile coldness of the stony-hearted, to the rich warm Paradise of Trust and Love.” Miss Twinkleton’s fraudulent version tamely ran thus: “Ever engaged to me with the consent of our parents on both sides, and the approbation of the silver-haired rector of the district,—said Edward, respectfully raising to his lips the taper fingers so skilful in embroidery, tambour, crochet, and other truly feminine arts,—let me call on thy papa ere to-morrow’s dawn has sunk into the west, and propose a suburban establishment, lowly it may be, but within our means, where he will be always welcome as an evening guest, and where every arrangement shall invest economy, and constant interchange of scholastic acquirements with the attributes of the ministering angel to domestic bliss.”

When I read the first chapter, I assumed that opium would be a big part of Jasper’s character, but I’d also forgotten about it by the time we saw him partake of it again in Chapter 23. That scene did not disappoint though.

Hurry for another appearance by the mysterious old woman from Chapter 14! Unfortunately, it leaves us with even more questions about her.

I wanted to comment right away because now I’m going to read Leon Garfield’s conclusion to The Mystery of Edwin Drood. I don’t believe it’ll satisfy me because no matter how great it is, I’ll always be wondering how Dickens’s version would have differed. But I feel like I’ve got to read some kind of conclusion and Garfield is a writer whose prose I believe equals Dickens’s, so it’s my best bet. But I didn’t want his additions to get mixed up in my head with what Dickens wrote while I’m commenting.

I also hope to watch the promising looking 2012 miniseries adaptation. I considered doing a recap of it for Dickens Club like I did for the Bleak House and Little Dorrit miniseries. But I’ve rejected that thought since I’d only have read the book and watched the miniseries once before doing so, meaning I wouldn’t notice as many little changes and little bits of fidelity. It just wouldn’t be as good.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Fellow Inimitables,

I sense that we are all “smitten, decapitated” (cf. “Chariots of Fire” film) by this mystery novel of THE Inimitable!

As Rachel describes, it is a kind of tragedy that we cannot know what Dickens intended. With that comes a kind of juicy invitation to imagine . . . .

#1. Datchery: I continually delight in Dickens’ delightful, quirky characters such as Datchery. Thanks much to Rachel and Chris for excellent “sleuthing” about his possible identity. How delightful to imagine Bazzard in this disguise and mysterious role!

The word, “cathedraly,” is now part of my lexicon!

#2. Dr. Christian’s stunning gift: Dr. Christian, if you are reading, let me echo Rachel and Boze’s joyous gratitude at the receipt of this treasure: “the most surprising, thoughtful, treasured gift: a complete set of the first edition of The Mystery of Edwin Drood–all six installments!”

Wow! I had the privilege of seeing these first edition “relics” up close. Marvelous. How they make us feel a direct connection to Dickens! What a remarkably generous gift!

#3. Princess Puffer: What a captivating figure! Enigmatic, shadowy—a female Jasper, who knows his opium-induced secrets and has some possible hold over him.

#4: Opium den: I sense that Dickens’ depiction of the opium den and its inhabitants shows us a “shadow side” (in the Jungian sense) of London and and of respectable Victorian society.

#5: Redemption arc?: I keep wondering about Jasper, who succumbs to the influence of opium and its widening grip on his mental and physical being. Were he to “detox,” would he have the clarity of mind and conscience to mend his ways and discover real love (as opposed to the obsessive, dominating, threatening stance towards Rosa)?

Dickens, you must be chuckling happily, as we anguish and delight reading Drood!

Daniel

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’d like to give my thoughts on some of the theories about the mysterious Datchery that were discussed in our supplemental reading. I felt I should read all the arguments put forward by the theorists themselves instead of just G. K. Chesterton’s summaries, but I couldn’t find a way to read most of them online for free. I was able to read Andrew Lang’s more detailed analysis though.

The Puzzle of Dickens’s Last Plot, by Andrew Lang (gutenberg.org)

Before I begin, I should mention something. A temptation in this speculation is to dismiss theories on the grounds that we don’t like them but it’s totally possible that if Dickens had completed Edwin Drood, he would written something we wouldn’t like. He wasn’t perfect after all. Still, I don’t think we can just say, “well, Dickens wasn’t perfect; he might have written old thing,” either. I’ll do my best to navigate this minefield.

Theory 1: Datchery is Bazzard in disguise, likely as agent of Grewgious. This is the theory Rachel prefers, and it makes a lot of sense. To my way of thinking, it almost makes too much sense. I agree with G. K. Chesterton that it would have been anticlimactic to reveal that kooky old guy was really…another kooky old guy in disguise. Still, like I said, my not liking the idea doesn’t mean Dickens disliked it.

Theory 2: Datchery is Edwin Drood in disguise. This theory was begun by Richard Proctor and improved upon by Andrew Lang and William Archer. John Jasper tried to kill Edwin while they were both high on opium and believed he succeeded. Edwin revived first though and fled Cloisterham. He had hazy memories of his beloved uncle trying to strangle him but wasn’t sure if they true memories or the result of opium, so he decided to return in disguise to observe his uncle’s behavior. This would make for an exciting story, but I’m not quite sold on it. Why does Datchery express surprise on being told where Jasper lives if he’s really Edwin? Is he just really, really in character? Also, I can’t help but note that this feels like a retread of John Harmon’s story in Our Mutual Friend. (A young man is unsuccessfully murdered then adopts a false identity, letting everyone believe he really is dead, so he can do some spying.) That doesn’t disprove anything of course. Dickens reused a number of tropes in his stories, and it’s not necessarily out of character for a great writer to do so. William Shakespeare after all followed up As You Like It with Twelfth Night. (Both plays are about a young woman who disguises herself as a man which allows her to get to know the man she loves in a way she otherwise wouldn’t. Both plays also feature another, haughtier woman who boasts she will never fall prey to love but ironically falls hopelessly for the man who is really a woman.) Dickens and Shakespeare were also both commercial artists and maybe those kinds of stories were what their respective publics were demanding at the time. On the other hand, we know Dickens specifically reread David Copperfield before writing Great Expectations so he wouldn’t repeat it, and I personally see evidence that he was entering an experimental phase with Our Mutual Friend. I just can’t quite convince myself that he would so blatantly recycle the main plot of his last book at this point in his career. (A subplot? Yes. The main plot? No.) I do really like Proctor’s idea for the climax of the book and how it would make sense of the scream Durdles recounts hearing in the vault on Christmas Eve.

Theory 3: Datchery is Helena Landless in disguise. This theory was pioneered by Cuming Walters. A big part of me gravitates toward this one because it answers a question with which the book leaves me. Dickens lavishes a lot of vivid description on Helena’s personality, making it seem like she’s going to be a major player in the story. But the only role he gave her in what he was able to write of the book was that of confidant to Neville and Rosa. If Helena wasn’t going to play a big part in the rest of the story, I feel like she’s one of its flaws. (It’s true that sidekicks often have more vivid personalities than main characters but those are typically comedic sidekicks, not serious ones like Helena.) On the other hand, if this theory were true, she might still very well be a flaw in the book because I don’t really buy that she could pull off this disguise. Unlike Bazzard, she has not connection to the theatre. It’s true that she would disguise herself as a boy when she and her brother would run away as children. That is one of the main things cited as evidence for this theory. But none of those escapes were successful, were they? And, unlike Edwin Drood, Helena isn’t presumed dead or anything. Wouldn’t someone catch her sneaking out of the school at some point? And wouldn’t someone in town eventually have asked, “how come we never see Datchery and Miss Landless in the same room?” Dickens had never had a female character successfully impersonate a man or vice versa before. That doesn’t disprove the theory since, like I said, it seems like he was trying new things in his last few books. But it makes the theory impossible to prove or disprove as we have no way of knowing how Dickens would have handled such a plot point.

Theory 4: Datchery really is a new character that Dickens was introducing to the story. This theory is mine. (I hope I am not being influenced by Leon Garfield in this. It actually occurred before I read what he chose to do with Datchery, which was similar to what I suggest but not quite the same.) I wonder if Datchery is someone who knew Jasper from somewhere else a long time ago and suspected his true nature. Hearing about Edwin’s murder (somehow-this theory isn’t particularly well thought out), he guessed who might be the culprit and decided to go to Cloisterham to do a little detective work.

All of these theories raise as many questions as they answer but we must remember Dickens would have had half a book to make sense of them.

LikeLike

I wasn’t going to comment about Leon Garfield’s conclusion to Edwin Drood that I read because this is Dickens Club, not Garfield Club. However, reading it was such an interesting experience for me that I can’t resist. Hopefully, some of you will be interested.

The writing itself is wonderful but at first, I couldn’t really enjoy it because I kept wondering things like “would Dickens have used that phrase” or “is that in keeping Dickens’s perspective?” But eventually, I stopped thinking about different authors and just enjoyed the writing and the story for what they were.

There’s something that really bugs me though. In his last scene with Crisparkle, didn’t Dickens have Grewgious tell him about Jasper’s attempt at blackmailing Rosa? Because Garfield acts like that didn’t happen at all. I’m not saying Crisparkle would have directly confronted Jasper about it, but shouldn’t that be in his head during future interactions with him?

Whatever discrepancies there would be with the prose, I was hoped what Dickens wrote and what Garfield wrote would add up to a cohesive story. They…sort of do. But it’s disappointingly obvious to me that the book changes direction when Garfield’s hand takes over. To me, the last couple of chapters Dickens completed for Edwin Drood really feel like it’s leading up to Grewgious, Crisparkle, Tartar, possibly Neville and likely Helena teaming up to take down Jasper somehow. But Garfield’s conclusion sidelines all of them for most of it and focuses mainly on Datchery and Grewgious. To be fair, that makes a certain amount of sense. Datchery is the only character who seems like a detective and Grewgious is the character with the biggest motivation for specifically helping Rosa (except for maybe Helena.) I can’t say for sure that Dickens wasn’t going to do the same thing. Still, it really does feel like he was setting up Tartar to be a much bigger character than ends up being in Garfield’s conclusion. It’s also a bit jarring that Dickens presented Rosa leaving Cloisterham as a big deal, but Garfield sends her back as quickly as possible. (That also means we don’t get much more of Miss Billickin. Bummer.)

Garfield does a great job of recreating Dickensian horror and Dickens’s sense of humor. (Those things shouldn’t come as a surprise to those familiar with his work.) The line about a maidservant being “gifted with second sight by way of compensation for a notorious lack of the first in the matter of seeing dust” sounds exactly like Dickens wrote it.

This may sound crazy given how much I’ve referenced Shakespeare in my recent comments, but I feel like in his conclusion, Garfield alludes to Shakespeare way too many times. Dickens did some Shakespeare references in Edwin Drood but not that many. Individually, any of Garfield’s references is fun but the cumulative effect got a little distracting for this reader. I wanted to yell, “OK, we get it already! You love Shakespeare!”

I mentioned before that I feel like if Helena wasn’t going to play a big part in the story, her characterization would have been a flaw. Garfield does give her a satisfyingly big role in the climax though I don’t love the way he handled it. It makes sense for Helena to show more vulnerability in the second half of the story than she did initially (like Estella in Great Expectations?), especially if she’s going to be a love interest. But it feels to me like Garfield just flipped a switch and made her a totally different character in the end. A more gradual “unthawing” of Helena would have been more satisfying, I think. Garfield makes an interesting suggestion in one chapter that while Helena seems like the tougher woman, Rosa is the really tough one, but I feel like he isn’t interested enough in either character to really sell the idea.

While Garfield doesn’t follow through on Dickens’s intention (or what Forster remembered Dickens saying his intention was) of having the ring be the thing to convict Jasper, he does follow through on this bit. “The originality (of the situation) was to consist in the review of the murderer’s career by himself at the close, when its temptations were to be dwelt upon as if, not he the culprit, but some other man, were the tempted. The last chapters were to be written in the condemned cell, to which his wickedness, all elaborately elicited from him as if told of another, had brought him.” The chapter in which Jasper does this is chilling and one where Dickens’s and Garfield’s sensibilities perfectly align. On the one hand, Jasper can be seen as contemptible in the way he speaks of all his sins as if someone else committed them. On the other hand, he sounds so desperate and terrified that you can’t help but pity him and wonder if he really is the victim of someone or something else somehow. (According to my copy’s introduction by Edward Blishen, Garfield said that if Dickens had completed Edwin Drood, Robert Louis Stevenson wouldn’t have needed to write The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.) I’m convinced this scene is exactly what Dickens had in mind and part of me wants to recommend Garfield’s conclusion solely because of that.

Do I recommend the conclusion though? Well, I think whether or not to read a conclusion to a Dickens book written by another author is a decision that every Dickens fan has to make for themself. I suspect this is the one with the greatest prose though perhaps some others do better by the characters-apart from that last scene with Jasper.

LikeLike

Ch 21 – A Recognition

Mr Grewgious gets an idea. Rosa and Mr Tartar seem to be getting ideas, too!

Ch 22 – A Gritty State of Things comes on

In my humble opinion, this could/should have been at least 3 chapters. I humbly suggest the following divisions:

Topic 1 – Rosa’s meeting with Helena and Mr Tartar’s chambers.

A meeting between Rosa and Helena, complicated by the need to hide it from Jasper should he or his agent be watching, is achieved by using Mr Tartar’s well-placed chambers as a means of communication. Additionally, it fills in Mr Tartar’s character and allows us – and Rosa – to see his chambers and clues us in to Rosa’s blossoming feelings for him. Mr Tartar, though a well trained sailor, has a bit of OCD – much like Dickens himself – and I submit that should he and Rosa marry, Rosa will soon be at her wits end, à la Dora Copperfield, trying to maintain his strict version of ship-shape-ness.

Through this meeting we also see Helena’s blossoming feelings for Mr Crisparkle, as well as her capability of devising shrewd schemes. Her suggestion that Jasper might “warn [Mr Tartar] off from Neville” and thus expose himself and/or his designs against Neville is likely to play a part in exposing the truth. At the very least this suggestion gives us a better understanding of how a young Helena might have planned escape from the horrors of growing up in Ceylon (see Ch 7).

Topic 2 – Finding lodgings for Rosa and Miss Twinkleton; Billickin/Twinkleton hostilities.

We are introduced to another inconvenienced and petulant landlady, Billickin. Her sparring with Miss Twinkleton reminds me of Mrs Crupp and Peggotty (see DC ch 34). The promise of comic relief, in my opinion, hasn’t been realized; hopefully Dickens meant to edit Billickin’s scenes to make her funny instead of tedious. Miss Twinkleton’s snooty-but-loveable-romantic nature resembles a Miss La Creevey (NN), Miss Tox (DS) or Mrs Todgers (MC). Her role as both mother figure and friend should support Rosa through whatever trials await her through the unfinished second half of the story.

Topic 3 – Up the River with Mr Tartar.

This should be a stand-alone chapter expanded to get a better feel for the Tartar/Rosa relationship, like the Bella Wilfer’s “date” with her father or Bella’s wedding day excursion (OMF Bk 2 Ch 8, Bk 4 Ch 4 respectively). Mr Tartar’s man, Mr Lobley, is introduced. Is he another Mark Tapley (MC) or is he a Littimer (DC)? – I vote for Tapley.

Ch 23 – The Dawn Again

Princess Puffer proves to be more than simply an addle brained old junkie. Whatever her motive for wanting to know Jasper’s secrets, she shrewdly manipulates him in her opium den by knowing her trade too well and knowing her customer far better than he suspects. She now succeeds in drawing him out verbally – and locally in that she successfully follows him to Cloisterham. In Cloisterham, however, the narrow scope of her shrewdness becomes apparent. She talks too much to Dick Datchery and Deputy, just as she had talked too much to Edwin on her earlier visit (Ch 14). Nonetheless, this is a good thing because it gives Mr Datchery important information and clues that he will use, or no doubt would have used, to solve the Mystery of Edwin Drood.

This last chapter brings us back to the beginning. In his article “Who Cares Who Killed Edwin Drood? Or, On the Whole, I’d Rather Be in Philadelphia” (link below), Gerhard Joseph discusses, among other things, repetition and “the principles of narrative cyclicality or ‘framing’”. Specifically in Edwin Drood Joseph says, “the last completed chapter provides a direct narrative echo of the opening chapter . . . one may read into the cyclicality of the two opium dreams a kind of retrospective allegory on the repetitive nature of Dickens’s art and life”. (170)

John Forster entitled this last chapter “The Dawn Again”. I submit a different name for it – “Noontide”. I offer this because, assuming Dickens’s intent was to end the novel with Jasper’s jailhouse, death row, confession, the cyclical organization of the novel, as per Joseph above, would likely have revolved around Jasper’s opium induced dreams. The first chapter introduces us to his dream world while he is contemplating murder. Ch 23 continues that dream world but, apparently, after the murder has been committed. The final chapter would arguably be Jasper’s confession, either opium-induced or, as Daniel suggests, after he’s detoxed and is lucid. Thus, Ch 1 Dawn – Ch 23 Noontide – Final Ch Dusk.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Q82pjGk0yVMODVjZ1lmH4BrF2WL8G9pP/view?usp=sharing

LikeLike

The most comprehensive treatise on Edwin Drood to date is The Mystery of Edwin Drood: Charles Dickens’ Unfinished Novel & Our Endless Attempts to End It by Pete Orford.

If you can’t get the book you can hear Dr Pete discuss it with Dominic Gerrard on the fantastic podcast, Charles Dickens: A Brain on Fire – two episodes: September 14, 2023 and May 15, 2024

LikeLike

Now that I’ve seen the 2012 Edwin Drood miniseries, I can’t resist sharing my thoughts with you guys. They’re going to be about the big spoilers though, so I implore you not to read this if you haven’t watched the series yet.

Choices were made and by choices, I mean mistakes. LOL. Just kidding. That makes it sound like I hate this version which I don’t. There are however three big wrinkles that writer Gwyneth Hughes adds to Dickens’s foundation, none of which I can say I love.

Twist 1: Neville and Helena’s biological father was also Edwin Drood’s father. Their mother told them this and part of their motivation for coming to England is to confirm it. I… don’t mind this, I guess, but I don’t really understand why Neville spends so much of the second half trying to prove it. How would the information clear him of suspicion?

Twist 2: John Jasper is really Edwin Drood’s half-brother. Their parents just said he his mother’s brother to clear him of the disgrace of illegitimate birth. He murdered his own father and it’s his body, not Edwin’s, that he stashed away in a tomb. This wild revelation is pretty true to the spirit of Dickens, but I question the need of it. I never felt like Jasper being jealous of Edwin’s engagement to Rosa was insufficient motivation for his hatred. I mean, it’s not sufficient in that it’s morally justified but it’s sufficient in that people sometimes petty, obsessive grudges in Dickens books (cf. Rosa Dartle, Miss Havisham, Bradley Headstone) and in real life. I don’t see a need for Edwin to be favored son to explain Jasper’s behavior. I’d rather the adaptation had included this twist or the one with the Landless twins. Having both of them feels gratuitous though I can’t say Dickens wouldn’t have done something like it. (You could argue that Rose Maylie being Oliver Twist’s maternal aunt was also pointless.) Of the two, I prefer this one.

Twist 3: Edwin Drood is alive. Jasper’s murdering him was just another of his hallucinations, one that happened to coincide with him leaving early for Egypt and not telling anyone. This is…just dumb. If you’re going to have Edwin be alive, I feel like either he should be Datchery or his uncle should be holding him a prisoner somewhere. (Maybe in that tomb?) Having him just happen to skip town on a whim on the same night Jasper imagined he murdered him, honestly made me laugh at its ridiculousness. (Also, what was with Jasper setting up Neville to take the blame if he wasn’t planning on murdering Edwin that night?) Having said all that, the ensuing scene where Jasper thinks his half-brother’s ghost has returned to haunt him when really Edwin is trying to help him, driving him to suicide is a great ending for the character. That scene kind of reconciles me to the idea though I still maintain it should have been handled differently.

The ending falls flat for me. Now that they know they had the same father, Edwin and Neville are suddenly best buds and are going to go into business together? If they could stand each other before, that was all they could do. Tartar is cut from this version and Rosa is contentedly single at the end. (Hughes has gone on record as feeling that seventeen is too young for a girl to get married.) To my own surprise, I find myself wishing she’d ended up with Neville. I never felt like they had any chemistry between them in the book or in this version but as it is, his earlier attraction to her just conveniently disappears once it’s served its purpose in the plot. It feels odd. I know having every hero and heroine get married at the end of a story is frowned upon these days, but you know what else is frowned upon? Crazy plot twists revealing that seemingly unrelated characters are related to each other and this version is very insistent about staying true to that part of Dickens’s formula. If you’re going to defy modern critical tastes with that aspect, I feel like you should go the whole hog and defy them in other ways too. Otherwise, it’s harder to defend the potential silliness of the ending with “they’re trying to be like Dickens.”

I feel kind of bad this comment has been so negative. There’s a lot of enjoy about the miniseries. The casting is very good (though I feel like Freddie Fox needed to be more appealing as Edwin Drood for us to root for his redemption.) So is the direction. (Diarmuid Lawrence was also one of the directors of the 2008 Little Dorrit miniseries you’ll remember I praised.) When it’s not too crazy, the writing is good too. (It gracefully gets around racist implications of Dickens’s text without feeling too revisionist. At one point, Neville laments that he has something of a tiger’s nature in him and Crisparkle gently suggests that’s his stepfather talking. While Dickens seems to have endorsed the idea that Ceylon has made the Landless twins wild and dangerous, he also wrote a lot about how abusive parents messed up their kids. Neville having internalized, as the kids say nowadays, racism from his stepfather feels like something Dickens would have written while being less, you know, racist.) I appreciate that the characters Dickens sets up as the heroes don’t get sidelined as they did in Leon Garfield’s continuation. (Though I feel like the pretext for involving Rosa in the climax is very thin.) I’d really like to recommend this miniseries, but a clunky ending casts such a big shadow over it that I have a hard time saying I like it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I feel like I should clarify a few things.

While I’ve described this miniseries as wild, it’s considerably less so than Stephen Knight’s recent Dickens adaptations. I’ll even say it feels more like Dickens than Marty Ross’s recent adaptations of his work for Audible.com.

(This is going to get into spoilers.) I think I’ve figured out why the outlandish revelation about Jasper’s true relation to Edwin bugs me in a way Dickens’s outlandish revelations about his characters’ relationships don’t. The question of Oliver Twist’s parentage is raised in the first chapter and as the story goes on, we want to know why Mr. Brownlow has a picture of his mother and why Monks has such a grudge against him. While we’re not given any initial reason to doubt the identity of Arthur Clennam’s parents, we do know there’s some kind of dark secret in his family’s history, something connected to the Dorrits. Crazy as that secret turns out to be, we’re kind of primed for it. Smike’s parentage is the most random of all these but there was one chapter where Nicholas asked him about his history. By contrast, the 2012 Edwin Drood miniseries feels like it’s answering a question that never occurred to me. It’s a Dickensian plot twist for the sake of a Dickensian plot twist without understanding how they work. Maybe that’s too harsh. I’m guessing Gwyneth Hughes didn’t want Edwin to die but did want Jasper to have murdered somebody. The twist does serve to drive him to suicide much as the revelation about Smike drove Ralph Nickleby to it. And I like the misdirection where we think our heroes are going to discover Edwin’s corpse but instead, they find his father’s.

LikeLike