Wherein your co-hosts of The Dickens Chronological Reading Club 2022-24 (#DickensClub) wrap up our first two weeks with our twenty-fourth read, Our Mutual Friend; with a chapter summary and discussion wrap-up.

By the members of the #DickensClub, edited/compiled by Rach

Friends, what a river journey this book has been already, as well as a unique vision of Victorian London. From those who make their living by pinching from corpses, to an articulator of bones, to a street ballad singer with a wooden leg hired by a newly-rich couple to read to them of an evening. Dickens is the master of atmosphere and the eccentric or grotesque. But far more “grotesque” than the image of the skeletal Frenchman in Mr Venus’s bone shop, is, perhaps, Dickens’s vision of the Society surrounding the Veneerings and the Lammles.

One question, for those who haven’t read this novel before, might be: Whom do we trust? Who is this Julius Handford, or John Rokesmith, and what interest does he have in the Boffins and the Wilfers? What are we to make of the dissolute, drifting Eugene Wrayburn, or the delightfully honest but money-loving Bella Wilfer? What of Silas Wegg and Mr Venus? And how will all of these stories connect?

But first, a few quick links:

- General Mems

- Our Mutual Friend, “Book the First”: A Summary

- Discussion Wrap-Up (Weeks 1-2)

- A Look-Ahead to Weeks 3 & 4 of Our Mutual Friend (11-24 June, 2024)

General Mems

SAVE THE DATE (and let us know which works for you)! For our Zoom chat on Our Mutual Friend, we’re looking at either Sat, Aug 10 or Sat, Aug 17th, 2024.

If you’re counting, today is Day 889 (and week 128) in our #DickensClub! This week and next, we’ll be reading “Book the Second: Birds of a Feather,” Chapters 1-16, of Our Mutual Friend, our twenty-fourth read as the group. Please feel free to comment below this post for the third and fourth weeks’ chapters or use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter.

For our introduction to this marvelous novel, and our eight-week reading schedule, please click here.

No matter where you’re at in the reading process, a huge “thank you” for reading along with us. Heartfelt thanks to our dear Dickens Fellowship, The Dickens Society, and the Charles Dickens Letters Project for retweets, and to all those liking, sharing, and encouraging our Club, including Gina Dalfonzo, Dr. Christian Lehmann and Dr. Pete Orford. Huge “thank you” also to The Circumlocution Office (on twitter also!) for providing such a marvellous online resource for us. And for any more recent members or for those who might be interested in joining: the revised two-and-a-half year reading schedule can be found here. If you’ve been reading along with us but aren’t yet on the Member List, we would love to add you! Please feel free to message Rach here on the site, or on twitter.

Our Mutual Friend, “Book the First”: A Summary

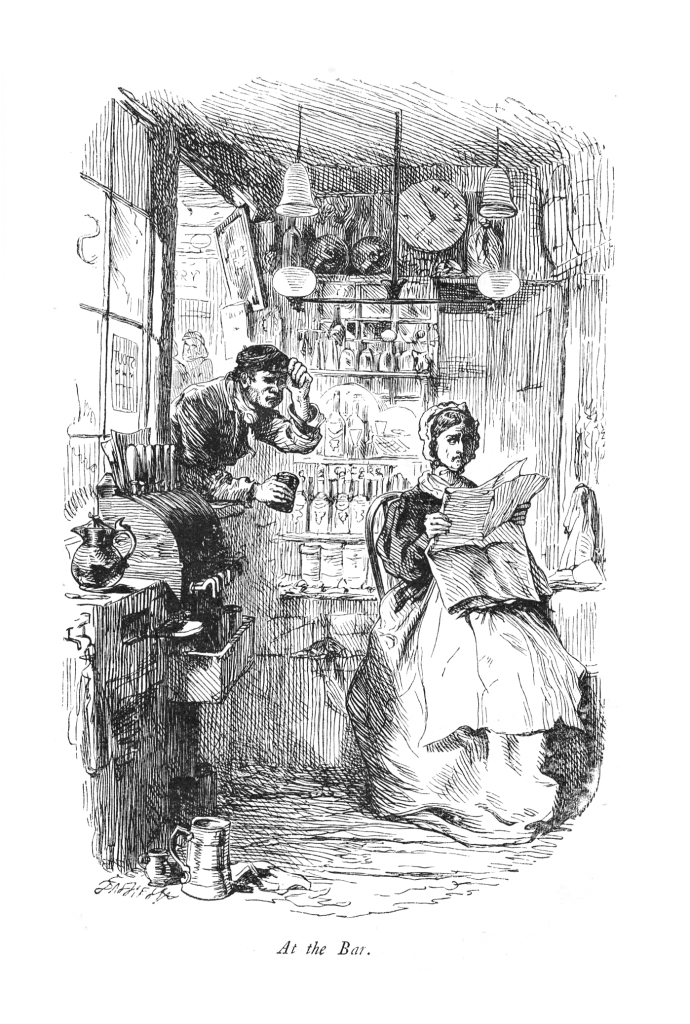

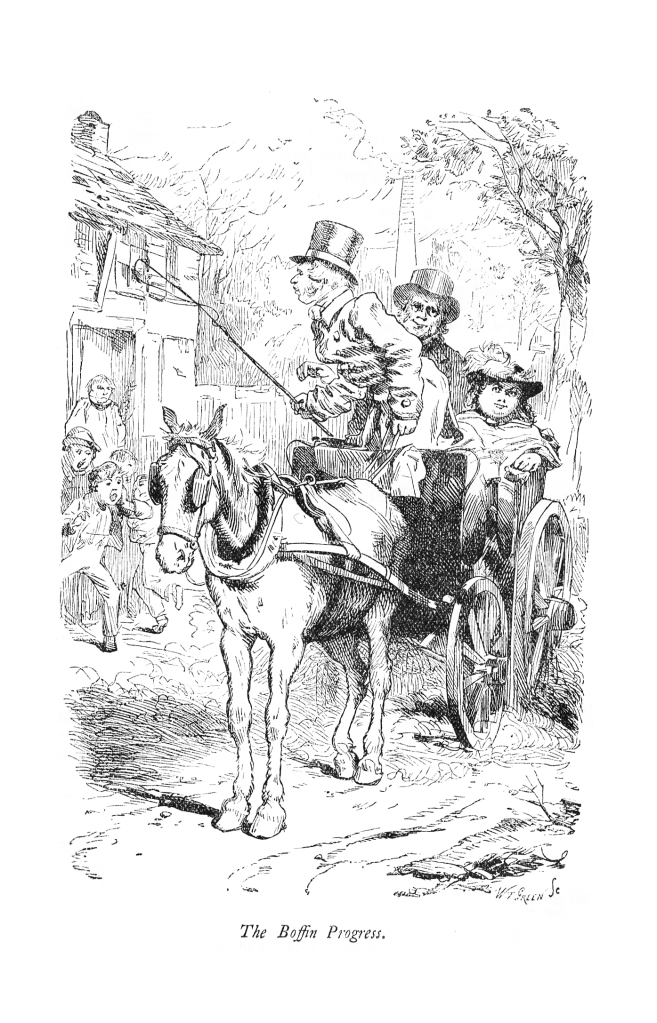

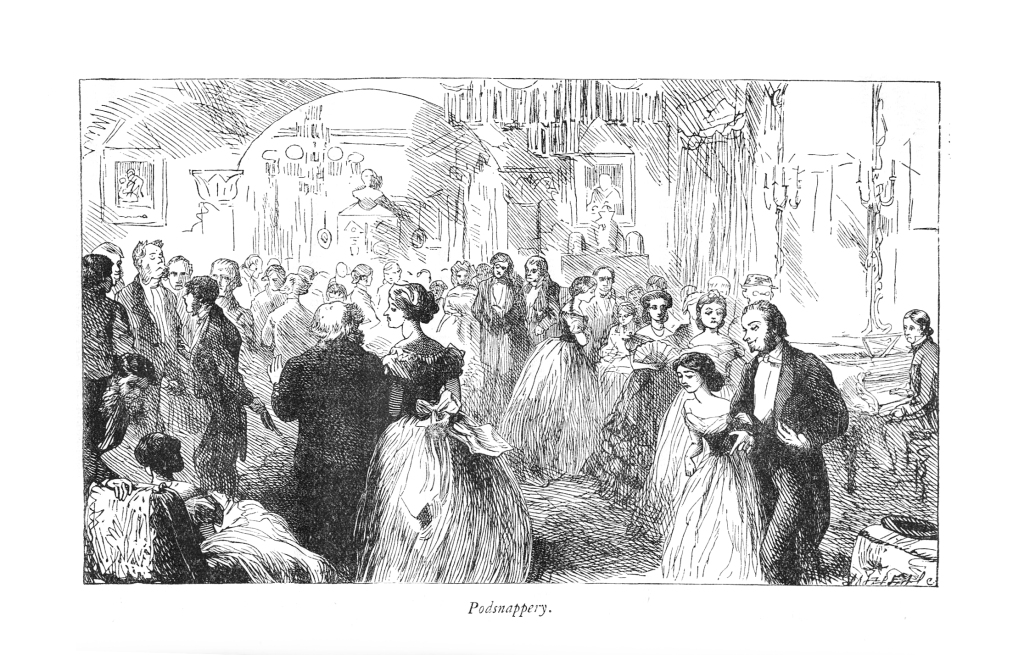

(Illustrated by Marcus Stone. Images below are from the Charles Dickens Illustrated Gallery.)

We begin our journey on the River. Lizzie Hexam and her father—“Gaffer” Hexam”—row along the Thames, Lizzie’s father trying to pick the pocket of a corpse, while rebuking Lizzie for seeming to shudder at his work, and at the river from which they gain their livelihood.

“The very fire that warmed you when you were a babby, was picked out of the river alongside the coal barges. The very basket that you slept in, the tide washed ashore. The very rockers that I put it upon to make a cradle of it, I cut out of a piece of wood that drifted from some ship or another.”

Lizze and her father are interrupted by a man calling himself the partner of “Gaffer,” who denies further association with the man because he was accused of stealing from a “live” man. Lizze and Gaffer Hexam tow in the corpse to shore.

“‘—Arn’t been eating nothing as has disagreed with you, have you, pardner?’

‘Why, yes, I have,’ said Gaffer. ‘I have been swallowing too much of that word, Pardner. I am no pardner of yours.’

‘Since when was you no pardner of mine, Gaffer Hexam Esquire?’

‘Since you was accused of robbing a man. Accused of robbing a live man!’ said Gaffer, with great indignation.

‘And what if I had been accused of robbing a dead man, Gaffer?’

‘You couldn’t do it.’

‘Couldn’t you, Gaffer?’

‘No. Has a dead man any use for money? Is it possible for a dead man to have money? What world does a dead man belong to? ‘Tother world. What world does money belong to? This world.”

We then meet the Veneerings, and their lavish and new surroundings, entertaining guests. One of them, a lawyer named Mortimer Lightwood, accompanied by his dissolute fellow lawyer Eugene Wrayburn, tells the story of the Harmon fortune, made out of “Dust” mounds, and the various things found in these heaps. Old Mr Harmon has recently died, leaving his entire estate and fortune to his son John Harmon, on one condition: he must marry a girl chosen by his father, whom he has never met. If he refuses this, the Harmon fortune will go to the faithful servant, Mr Boffin, who helps to manage the estate and dust mounds.

“‘The man,’ Mortimer goes on, addressing Eugene, ‘whose name is Harmon, was only son of a tremendous old rascal who made his money by Dust…By which means, or by others, he grew rich as a Dust Contractor, and lived in a hollow in a hilly country entirely composed of Dust. On his own small estate the growling old vagabond threw up his own mountain range, like an old volcano, and its geological formation was Dust. Coal-dust, vegetable-dust, bone-dust, crockery dust, rough dust and sifted dust,—all manner of Dust.’”

Just as he is finishing his tale, a message arrives: young John Harmon has drowned. The messenger, Charlie Hexam (son of Gaffer Hexam), takes Lightwood and Wrayburn to see the body which has been identified by the ship’s steward. Another man—Julius Handford—comes to witness, but he is unable to look at the corpse, and his evasive replies make him suspect. At the inquest, it is declared that the conditions of John Harmon’s death are suspicious.

“Upon the evidence adduced before them, the Jury found, That the body of Mr John Harmon had been discovered floating in the Thames, in an advanced state of decay, and much injured; and that the said Mr John Harmon had come by his death under highly suspicious circumstances, though by whose act or in what precise manner there was no evidence before this Jury to show.”

We then visit the intended bride to be, the spirited and occasionally prickly Bella Wilfer, now having to wear “ridiculous” mourning for a man (John Harmon) whom she has never met.

“‘It’s a shame! There never was such a hard case! I shouldn’t care so much if it wasn’t so ridiculous. It was ridiculous enough to have a stranger coming over to marry me, whether he liked it or not. It was ridiculous enough to know what an embarrassing meeting it would be, and how we never could pretend to have an inclination of our own, either of us. It was ridiculous enough to know I shouldn’t like him—how could I like him, left to him in a will, like a dozen of spoons… Those ridiculous points would have been smoothed away by the money, for I love money, and want money—want it dreadfully. I hate to be poor, and we are degradingly poor, offensively poor, miserably poor, beastly poor. But here I am, left with all the ridiculous parts of the situation remaining, and, added to them all, this ridiculous dress!’”

Bella’s family, not well off, take in a new lodger, another mysterious man who is unable to provide them with references, but who is able to pay immediately for his room. He gives his name as John Rokesmith. Bella is suspicious of him instantly.

A one-legged street singer and ballad-seller named Silas Wegg is approached by Harmon’s old servant, Mr Boffin, who hires Wegg to read to him, and Wegg proves himself to be sharp at making bargains for himself. He instantly takes on the position for a higher rate than proposed.

Meanwhile, Rogue Riderhood, the man who had called himself the partner of Gaffer Hexam, is making trouble at the Six Jolly Fellowship Porters, and the innkeeper, Miss Abbey, throws him out. Gaffer has also been denied access, due to Rogue’s envious insinuations that Gaffer murders corpses before robbing them. Lizzie stands up for her father when Miss Abbey begs her to leave Gaffer for the sake of her own future and reputation. But Lizzie is also looking out for her younger brother, Charlie, and has saved up some money to help him go to school, and board nearby, so as to get at least him away from their current life. Charlie leaves. When Lizzie tries to break the news gently to her father, he disowns Charlie with such violence—and with a knife in his hand—that he frightens Lizzie. Her father is surprised and remorseful at her fear.

Silas Wegg, feeling himself up a step higher in the world, would like to buy back the leg bone that he sold to Mr Venus, articulator of bones, though the latter cannot immediately consent. Wegg also notices Venus’s lowness of spirits, due to the latter’s heartsick devotion to a woman—whom we find out is Rogue Riderhood’s daughter—who will not marry him because of her objection to his business.

“‘Mr Wegg, not to name myself as a workman without an equal, I’ve gone on improving myself in my knowledge of Anatomy, till both by sight and by name I’m perfect. Mr Wegg, if you was brought here loose in a bag to be articulated, I’d name your smallest bones blindfold equally with your largest, as fast as I could pick ‘em out, and I’d sort ‘em all, and sort your wertebrae, in a manner that would equally surprise and charm you.’”

More connections begin to form as Boffin meets with Lightwood about his will, and securing his fortune against it going to anyone other than Mrs Boffin. Mr Boffin also wishes to advertise a 10,000-pound reward for the person who can help find the murderer of John Harmon, beloved of himself and Mrs Boffin from Harmon’s childhood, before he went abroad for school. John Rokesmith then introduces himself to Mr Boffin, and offers himself as a secretary, and they agree to discuss it further at another time.

Mrs Boffin has plans: she not only wants to offer a home to the disappointed Bella Wilfer and introduce her in society, but even to adopt a child who might then be named John Harmon, in the dead man’s honor. The Reverend Mr Milvey agrees to assist them with their endeavor. When the Boffins visit Bella, Bella agrees to their proposal, and they run into the Wilfer’s lodger, Mr Rokesmith, their mutual friend.

“‘By-the-bye, ma’am,’ said Mr Boffin, turning back as he was going, ‘you have a lodger?’

‘A gentleman,’ Mrs Wilfer answered, qualifying the low expression, ‘undoubtedly occupies our first floor.’

‘I may call him Our Mutual Friend,’ said Mr Boffin.”

Returning to the world of the Veneerings, we are introduced to two friends of theirs, Alfred Lammle and his new wife, Sophronia, both of whom have married one another under the mistaken impression that the other was wealthy—primarily due to the Veneerings. This hate-match turns into a match of conspirators, as they mutually agree that they must scheme their way to fortune. Another friend of the Veneerings, the Podsnaps, are celebrating their daughter Georgiana’s birthday, and the Lammles are quick to befriend her.

In Lightwood and Eugene’s shared digs, they are visited by Roger “Rogue” Riderhood, who, now that there has been an enormous reward offered for any who can lead to the murderer of John Harmon, accuses Gaffer Hexam of the murder.

“‘Alfred David.’

‘Is that your name?’ asked Lightwood.

‘My name?’ returned the man. ‘No; I want to take a Alfred David.’

(Which Eugene, smoking and contemplating him, interpreted as meaning Affidavit.)”

Accompanying Riderhood to the inspector—who is suspicious of Riderhood, the men all then go to find the Gaffer at his home. Eugene takes particular interest in Lizzie as she anxiously waits for her father to return. Lizzie calls out for her father. Riderhood goes out onto the water in search of him, and only finds Gaffer’s empty boat. When the boat is later dragged to shore, they find the corpse of Gaffer Hexam tied to it.

Meanwhile, the Boffins are adjusting to their change in fortunes. Their beloved old bower will be taken care of by Silas Wegg, and Mr Boffin has hired Rokesmith on as his secretary—he is adept and resourceful, and only wishes not to have any face-to-face contact with Mortimer Lightwood.

Still, however, there is something amiss: Mrs Boffin has seen the ghosts of Mr Harmon, John Harmon, and the sister who had died previously.

Still in search of an orphan to adopt, the Boffins visit old Betty Higden, a laundress and child-minder.

Rokesmith, who is something of a go-between at the Boffins’s and the Wilfers’s residences as Bella awaits the Boffins’s new home to be ready for her reception, finds that Bella is cold and unwelcoming to him. Still, however, she is beautiful. The Boffins begin to receive invitations from the “best” in Society as they take residence in their new home.

Discussion Wrap-Up (Weeks 1 & 2)

Miscellany & What We Loved–or Didn’t; Reactions to the Intro

The Stationmaster, like Daniel and Boze, are coming to Our Mutual Friend for the first time, which is immensely exciting! The Stationmaster is doubtful that it will be a favorite with him–but then again…? Here, he mentions a few troublesome first impressions:

Later in his reading, he writes:

Daniel reacts to the Introduction to Our Mutual Friend that we posted the week before last:

Dana, like Boze and I, is loving the David Troughton audiobook!

And I summarize a few thoughts from our first portion:

Dickens’s Writing Lab: Characterization

Some notes on characterization, from the Stationmaster:

Dickens’s Women: Bella & Lizzie

And the Stationmaster also begins our discussion on our leading ladies–aside from a third who will shortly be introduced:

A Look-Ahead to Weeks 3 & 4 of Our Mutual Friend (11-24 June, 2024)

This week and next, we’ll be reading “Book the Second: Birds of a Feather,” Chapters 1-16, of Our Mutual Friend. This portion was published in monthly parts (installments VI-X) between October 1864 and February 1865.

Please comment below with your thoughts on this portion, or use the hashtag #DickensClub if commenting on Twitter/X.

If you’d like to read it online, you can find it at a number of sites such as Gutenberg.

Excellent, rich round-up, Rach and Boze…many thanks!

I think Lizzie and Bella may be my two favorites of Dickens’ young women protags. They provide a rather delicious contrast to one another, too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Inimitables,

I fully concur with Dana Rail: Bella and Lizzie are two marvelous female characters, who are so very different. Both are wonderfully likeable (Bella for her blunt honesty and unaffected affection for money, which her family lacks) and Lizzie (for her fidelity and practical care of those entrusted to her).

Thanks so much, Rach, for the lucid recapitulation of character, plot, and setting. That really helps!

I am captivated by the immense contrasts of social and cultural life that Dickens depicts, and how he sees through the “veneer” of the world of pomp and pomposity, as well as the “heaps” of cast-away people and things of Victorian England—as true in our world today as then.

Like all great imagineers, Dickens helps us to see our own world and its proper enjoyments and many deceptions more clearly.

Eager to continue the journey of “Our Mutual Friend” and the unfolding of a powerful story, even parable, of illusory and real/true people, places, and things!

Blessings,

Daniel

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’d like to add another character to my list of those from Our Mutual Friend who seem like retreads from previous Dickens book. The “Analytical Chemist” reminds me of the Chief Butler from Little Dorrit.

Anyway, I’m up to Chapter 7 in these two weeks’ reading. Here are some thoughts.

I love the description of the school in Chapter 1 and the descriptions of Bradley Headstone. Dickens does a great job of conveying his personality.

“Bradley Headstone, in his decent black coat and waistcoat, and decent white shirt, and decent formal black tie, and decent pantaloons of pepper and salt, with his decent silver watch in his pocket and its decent hair-guard round his neck, looked a thoroughly decent young man of six-and-twenty. He was never seen in any other dress, and yet there was a certain stiffness in his manner of wearing this, as if there were a want of adaptation between him and it, recalling some mechanics in their holiday clothes. He had acquired mechanically a great store of teacher’s knowledge. He could do mental arithmetic mechanically, sing at sight mechanically, blow various wind instruments mechanically, even play the great church organ mechanically. From his early childhood up, his mind had been a place of mechanical stowage. The arrangement of his wholesale warehouse, so that it might be always ready to meet the demands of retail dealers history here, geography there, astronomy to the right, political economy to the left—natural history, the physical sciences, figures, music, the lower mathematics, and what not, all in their several places—this care had imparted to his countenance a look of care; while the habit of questioning and being questioned had given him a suspicious manner, or a manner that would be better described as one of lying in wait. There was a kind of settled trouble in the face. It was the face belonging to a naturally slow or inattentive intellect that had toiled hard to get what it had won, and that had to hold it now that it was gotten. He always seemed to be uneasy lest anything should be missing from his mental warehouse, and taking stock to assure himself.”

Jenny Wren’s fancies about angels remind me of Smike’s dream of Eden in Nicholas Nickleby.

Jenny is interesting in that compared to Oliver Twist and similarly long-suffering children in Dickens, she doesn’t have a particularly sweet or innocent personality. Except for her visions of the afterlife, she’s more like a more fun version of crabby Susan Nipper from Dombey and Son. (Susan Nipper is fun to read about of course but Jenny seems like she’d be fun to actually hang out with-as long as you didn’t get on the wrong side of her wit anyway.) She even says she dislikes children, normally something a Dickensian villain would say. (From what I understand, the role of saintly child in this book will be filled by Betty Higden’s Johnny.) The scene of Jenny scolding her alcoholic father like he’s her child is simultaneously one of the funniest and most heartbreaking things Dickens ever wrote. It really demonstrates how fast she’s had to learn to grow up. On a less depressing note, this bit is hilarious.

“You have got good measure, Miss What-Is-It?”

“Try Jenny.”

I don’t really get what the Lammles revenge plan is supposed to be so far. It seems like it has more to do with Georgiana Podsnap than the Veneerings against whom they want revenge. It’ll probably make sense by the end though.

Even though he’s a villain, I’ve got to say Fledgeby makes a good point here.

“Look here,” said Fledgeby. “You’re deep and you’re ready. Whether I am deep or not, never mind. I am not ready. But I can do one thing, Lammle, I can hold my tongue. And I intend always doing it.”

“You are a long-headed fellow, Fledgeby.”

“May be, or may not be. If I am a short-tongued fellow, it may amount to the same thing. Now, Lammle, I am never going to answer questions.”

“My dear fellow, it was the simplest question in the world.”

“Never mind. It seemed so, but things are not always what they seem. I saw a man examined as a witness in Westminster Hall. Questions put to him seemed the simplest in the world, but turned out to be anything rather than that, after he had answered ‘em. Very well. Then he should have held his tongue. If he had held his tongue, he would have kept out of scrapes that he got into.”

Since I said before that supporting characters in Our Mutual Friend strike me as inferior versions of ones from other Dickens books, I’d like to take the opportunity to mention something I think improves on a previous book. The way Fledgeby uses Riah as a scapegoat in his business is almost exactly how Casby uses Pancks in Little Dorrit but it’s more credible with Fledgeby and Riah with how Fledgeby takes advantage of racist stereotypes in his customers’ heads. The corresponding subplot in Little Dorrit, by contrast, relies entirely on Casby’s appearance of benevolence being ridiculously convincing. Of course, that also means the version in Our Mutual Friend is more depressing and less fun to read but oh well.

Charley Hexam has struck me as similar to another selfish little brother in Dickens, Tom Gradgrind. But it’s worth noting that when he confronts Eugene Wrayburn, he frames the issue in terms of protecting his sister, however selfish his motives might be. That’s more than Tom ever did for Louisa.

So far, I’ve been writing about his book as if I don’t know the broad outlines of the story. Dickens is such a great writer that it’s actually pretty easy for me to read the book that way. But there’s one scene that I really find interesting knowing what I know about what’s going to happen. If you don’t want any spoilers, skip the following paragraph.

I was surprised to find myself sympathizing with Headstone’s annoyance at Eugene Wrayburn in Chapter 6. Not that it justifies Headstone later going off the deep end or anything, but Eugene really was being insufferably rude. I don’t mean that as a criticism BTW. I think Dickens wants readers’ feelings to be up in the air at that point. We’re a little suspicious of both men and a little sympathetic to both of them too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Maybe instead of using Susan Nipper as a point of comparison, I should have said that Jenny Wren’s personality seems more like that of the Artful Dodger or Charley Bates than that of Oliver Twist. Except, you know, for the fact that she’s a decent person.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello dear friends!

I’ve been on a family holiday and was not able to contribute to our first section of this wonderful novel. I’ve enjoyed reading everyone’s thoughts.

Some of you have written of characters who seem to be re-imaginings of characters from earlier novels. I would like to submit that Mr Twemlow is kin to Cousin Feenix; Lady Tippins to Mrs Skewton; Mr Venus’s shop to The Old Curiosity Shop; Sloppy to Barnaby Rudge; Betty Higden to Mr Nandy or Miss Flite; the Boffins to the Cheeryble Brothers. The Veneerings remind me of what the Dorrits might have been if they had been more savvy, more politically minded, and less snobbish, yet they also remind me of the Kenswigs from “Nicholas Nickleby” in the way they speak and the way they collect people. This novel, in fact, seems almost a mash-up of the other novels – as though, and I think we’ve discussed this point before, Dickens kept writing and rewriting the same characters, situations, and social concerns, looking at them from different angles and perspectives – “Our Mutual Friend” is just the next iteration.

I’ve come across several critical accounts which speak of the comedy of “OMF” – humor, satire, the macabre, the absurd. Though I’ve read it several times, I’ve never really appreciated it from a comedic perspective because I was looking more at the story situation rather than the style in which it was written. This time through however I’m paying attention to the comedy. In particular in the interactions between Mr Boffin and Wegg, in the Wilfer family, in poor Mr Venus’s love situation, in the Veneerings, Lady Tippins and Lammle’s. Much of it is bittersweet – or sweetly bitter – but all of it is pointed and expertly played.

The only wrong note I see in Book 1 is when the narrator intrudes in Ch XVI with his observations to “my Lords and Gentlemen and Honorable Boards”. I realize this is quintessential Dickens, but I think his description of Betty Higden’s situation and her own speeches make the narrative intrusions unnecessary.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hmm, I’m not sure if I see Betty Higden as like Mr. Nandy or Miss Flite. She seems much more mentally on-the-ball than either of them. I agree with your other comparisons though.

LikeLike

My thought was that she is an older, marginalized person, little thought of or overlooked, except by kind people who take the time to see her worth.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I finished the reading for these weeks and I’m happy to say it worked better for me than the last two weeks’ reading. If you don’t want anything spoiled, don’t read this comment until you’ve read as much as I have.

I think Marcus Stone may have been better at drawing attractive young men and women than Phiz, Dickens’s usual illustrator. Case in point: the one of John Rokesmith and Bella Wilfer in Chapter 8.

The scene of Bella and her father enjoying a day out is so heartwarming. While some of Dickens’s heroines, like Lucie Manette and, to a lesser extent, Agnes Wickfield, have healthier relationships with their fathers than others, this is the only example of I can think of in Dickens of a father and a daughter having actually having fun together. I guess there are some in the “Christmas books,” like the Cratchits but that’s an entire family enjoying each other’s company, not a father and daughter specifically. (Some have speculated that Bella was based on one of Dickens’s own daughters, potentially making the scene even more heartwarming.) Even Bella’s confession of her increasing mercenariness and greed is heartwarming in that it shows how comfortable she is with her father.

Dickens goes right from that really heartwarming scene to one of the book’s most tearjerking parts: Johnny’s death. If books made me cry, that would have done so. Part of me is inclined to be cynical and say Dickens just included it because tearjerking scenes of children dying were part of his crowd-pleasing formula rather than because the story needed it. But to give in to that part seems heartless. (Besides which, the plot point does serve the story in that shows Bella behaving sympathetically and Rokesmith noticing.)

I like the idea of Mrs. Boffin deciding she shouldn’t worry so much about the child she adopts being cute and agreeable but isn’t it kind of a cheat to have her choose Sloppy? He may not be cute, but we know he’s a good, likeable character.

I love Dickens’s description of Pleasant Riderhood! It conveys her horrifying cynicism while also making her pitiable.

“As some dogs have it in the blood, or are trained, to worry certain creatures to a certain point, so—not to make the comparison disrespectfully—Pleasant Riderhood had it in the blood, or had been trained, to regard seamen, within certain limits, as her prey. Show her a man in a blue jacket, and, figuratively speaking, she pinned him instantly. Yet, all things considered, she was not of an evil mind or an unkindly disposition. For, observe how many things were to be considered according to her own unfortunate experience. Show Pleasant Riderhood a Wedding in the street, and she only saw two people taking out a regular licence to quarrel and fight. Show her a Christening, and she saw a little heathen personage having a quite superfluous name bestowed upon it, inasmuch as it would be commonly addressed by some abusive epithet: which little personage was not in the least wanted by anybody, and would be shoved and banged out of everybody’s way, until it should grow big enough to shove and bang. Show her a Funeral, and she saw an unremunerative ceremony in the nature of a black masquerade, conferring a temporary gentility on the performers, at an immense expense, and representing the only formal party ever given by the deceased. Show her a live father, and she saw but a duplicate of her own father, who from her infancy had been taken with fits and starts of discharging his duty to her, which duty was always incorporated in the form of a fist or a leathern strap, and being discharged hurt her.”

I was surprised Dickens revealed Rokesmith’s identity so early. I remembered it only being revealed at the end in adaptations. I believe he was right to do so though as I couldn’t really enjoy his romance with Bella while thinking that he was the one who murdered John Harmon. Dickens did a really good job of misdirecting readers to think that’s who he was.

In Chapter 15, Dickens goes directly from a really creepy scene (Bradley Headstone’s “proposal” to Lizzie Hexam) to a really sad one (Lizzie’s argument with Charley) to a really heartwarming one (Mr. Riah comforting her.)

I was surprised and intrigued to find Twemlow portrayed so sympathetically in Chapter 16. Previously, I’d just thought of him as a pathetic comedic figure. I love humorous characters who turn out to be dramatic. That’s to say, I love them when they’re done well, and Dickens was great at them.

“Ah! my Twemlow! Say, little feeble grey personage, what thoughts are in thy breast to-day, of the Fancy—so still to call her who bruised thy heart when it was green and thy head brown—and whether it be better or worse, more painful or less, to believe in the Fancy to this hour, than to know her for a greedy armour-plated crocodile, with no more capacity of imagining the delicate and sensitive and tender spot behind thy waistcoat, than of going straight at it with a knitting-needle. Say likewise, my Twemlow, whether it be the happier lot to be a poor relation of the great, or to stand in the wintry slush giving the hack horses to drink out of the shallow tub at the coach-stand, into which thou has so nearly set thy uncertain foot. Twemlow says nothing and goes on.”

A difference between Our Mutual Friend and every other Dickens book that comes to my mind is the emphasis on sexual tension as opposed to romance. By that I mean characters being attracted to each other but fighting that attraction. Both the main couples, John Rokesmith and Bella Wilfer and Eugene Wrayburn and Lizzie Hexam) have this and there’s one sided tension between Bradley Headstone and Lizzie. I don’t think this totally benefits the story since we’re roughly halfway through and we’ve had far more scenes of the couples being uncomfortable with each other than of them enjoying each other’s company. That means that as much as I want to love their love stories, which certainly have romantic outlines, I can’t root very hard for them to end up together. (Also not helping is that the end of Chapter 15 seems designed to make Wrayburn seem marginally better than Headstone-if at all.) But after three Dickens novels that were about characters suffering from unrequited love, it is refreshing and exciting to see him taking a new approach to romance.

LikeLike

Greetings, Inimitables!

I am really savoring the insights and comparisons that Adaptation Stationmaster and Chris are offering us.

Chris, this perception makes great sense: “Dickens kept writing and rewriting the same characters, situations, and social concerns, looking at them from different angles and perspectives – ‘Our Mutual Friend’ is just the next iteration.”

This ingenious ability to offer up myriad variations on a character “theme” helps us to see human goodness and foibles from so many angles. A kind of Dickensian cubism.

This riffing by Dickens engenders, for me, a sort of Greek tragedy catharsis: giving us readers the opportunity to reflect on the same goodness and foibles in our own lives . . . and, one hopes, to release the ones that don’t serve us or others!

Keep your insights and perceptions flowing! They really enrich my understanding of the novel and of Dickens’ genius.

Blessings, All!

Daniel

LikeLike

Welcome back, Chris!! And thanks to everyone for such wonderful comments…I’m still making my way through them. But I just wanted to add a few thoughts to one of the Stationmaster’s earlier comments. Firstly, I LOVED your focus on Jenny, and you hit on some of the reasons why she’s so marvelous. She is somehow in touch with the supernatural, and yet is snappy and impatient and human–in the most delightfully eccentric way. She is sometimes even harsh, though we understand fully why she is so, and has had to be so. For me, she’s right up there with Bella & Lizzie for three of Dickens’s great heroines.

I had the same impressions of comparing Charley Hexam with Tom Gradgrind, and the Fledgeby/Riah situation to that of Casby/Pancks, & Boze and I were discussing the latter the other day. I agree that F/R is a stronger and more effective “case,” as we see how F uses the prejudices of his time/place to put the blame on a Jewish man. I am proud of Dickens for going there. (In connection with Riah, we even hear some antisemitism from Eugene, which makes him far less likeable–I’m glad they cut those bits from the ’90s adaptation.)

As to the Stationmaster’s issue with Eugene (and I too have several issues with Eugene) in the scene with Headstone & Charley, I don’t blame Eugene as much here. Part of it is a class issue, part sheer etiquette. But I think we can’t quite fathom how insulting it would have been for Eugene to have had a schoolteacher to accompany his pupil and let his pupil–a boy–basically insult and take Eugene to task. Eugene is not only his elder, but is a gentleman, however poor a one. Headstone’s mere presence at the strange scene implies that something else is going on with Headstone–that he has an ulterior motive. I think, putting myself into the situation of Eugene, he is both cruel and just–and just downright reckless, though he can’t know Headstone’s nature yet. I think it is really well played in the ’90s adaptation: Eugene basically ignores Charley altogether, as the scene is really *about* Headstone & Eugene, & Eugene uses his wit and mockery to berate the schoolmaster for his rude behavior. I say all of this not to praise Eugene, but more to say that I *get*, given the circumstance, where it was coming from. It’s rather painful to watch/read, though, as we can guess at this point that Eugene is potentially making a formidable enemy.

LikeLike

Regarding the concept of Old Harmon’s dust mounds, I came across this short piece several years ago and post it for your consideration:

Dust

In this human life, we make a game of ridding ourselves of time’s evidence.

By Maya C. Popa

To have been a thing, any thing, is marvelous, but to have been among the class of creatures capable of naming is a singular wonder. The Old English word dustsceawung means the acknowledgment of dust as once having been other things, living beings or civilizations past. It is what’s called a kenning, a metaphorical collage-like expression—dūst meaning “dust” and sċēawung meaning “contemplation.” Dust requires us to confront our own transience and eventual anonymity, and doing so demands a flexible, inventive use of language.

There is “ashes to ashes, dust to dust,” from the Book of Common Prayer. We prefer the idea that we are made of stardust, that fine powder of the universe, lending scientific credence to our cosmic nature. Dust jackets protect books from that which is described within their pages—the grime and mess of life. Baldwin said the mind is like an object that picks up dust (“The object doesn’t know, any more than the mind does, why what clings to it clings”); Picasso said that the purpose of art was to wash the dust of daily life off of the soul. Eliot promised to show us fear in a handful of dust, and he was on to something.

Dust is by turns violent and gentle. Dust bowls, storms that killed humans and livestock alike, devastated the Midwest in the 1930s, as if to drive the point of the Great Depression cruelly home. But we must also allow for a dusting of sugar or of snow. Dust makes visible what is too insubstantial to be seen on its own. Motes floating in the air reveal breathable currents and give shape to beams of light reaching us from millions of miles away. Its particles provide a tangible measure of time, how long it’s been since an object was handled. And, naturally, out of this, we’ve devised a polite domestic chore, equipped with a soft feathered prop. In this human life, we make a game of ridding ourselves of time’s evidence.

The speculative insight and human anxiety at the heart of dustsceawung should, to my mind, make the word a strong contender for modern adoption. The effort to accept dust as our fate takes a whole life, and all of literature. We wait for the dust to settle, but it never does.

From Guernica, 12/6/21, https://www.guernicamag.com/dust/

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve been thinking about it and Johnny’s death might make me sadder than Jo’s death does in Bleak House, which is weird because Jo is a much more developed character than Johnny. Maybe it’s because Jo seemed like he was always going to die whereas a better life with the Boffins was being set up for Johnny. Or maybe they’re equally powerful tearjerkers and it’s just that I’m reading Our Mutual Friend for the first time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jenny Wren is the culmination of all the child-parents we’ve met to date – especially, she is Little Nell with a backbone, “bad” though it may be! She’s like an outspoken Amy Dorrit who takes her father to task for his failings and tries – unsuccessful – to talk him into behaving better. Perhaps if she were more mobile she would be able to police his drinking better.

The high comedy of Bk 2, Ch 3 “A Piece of Work” and Ch 4 “Cupid Prompted” is delicious. The scenes flow naturally with perfectly drawn characters whose dialogue is crisp and quick. The critique of the silliness of politics and of matchmaking is sharply pointed and hits its mark square. The two situations actually seem quite similar – that the Lammle’s aren’t as successful in bringing in their man, so to speak, is perhaps due to their Britannia (a.k.a. Georgiana Podsnap) is not yet keen to want him.

Fascination Fledgeby puts Jonas Chuzzlewit to shame, and Ralph Nickleby, Quilp, and Scrooge. One worries for poor Georgiana Podsnap – she may not suffer the same fate as Mercy Pecksniff as Fledgeby seems opposed to “pitching-in”, but marriage to Fledgeby won’t be the escape she’s looking for. That Mrs Lammle confides in Mr Twemlow regarding the plan her husband and Fledgeby have for Georgiana is wonderful – in the spirit of true sisterhood her woman’s conscience will not allow Georgiana to be “sold into wretchedness for life” without doing whatever little she can to stop it, though she will not go so far as to compromise herself in her husband’s (low) esteem. She is a coward but she has little choice because she, herself, has no way out of her own wretched life.

How different the scenes between Rokesmith and Bella (Bk 2, Ch 13) and Headstone and Lizzie (Bk 2, Ch 15). Rokesmith is so gentle, self-abnegating, and ever solicitous of Bella’s feelings whereas Headstone is harsh, insulting, self-absorbed, and completely ignorant of Lizzie. Every time I read Ch 15 I become irritated and wonder what on earth makes Headstone think that beginning a marriage proposal with the words, “You are the ruin of me”, will entice a woman to accept him. His wooing goes from bad to worse and I wonder why, as a school master, he didn’t take a hint from Miss Peecher and take the time to write his proposal in essay form on a slate, heavily edit it, and then edit it again before reading it aloud to himself and then rewrite it once more to make it at least a little palatable to Lizzie.

My 21st century sensibilities make me shake my head at Charley Hexam who paternalistically believes his sister will do whatever HE decides is in HIS best interests for her to do. We have seen other male characters who must care for their unmarried sisters after their fathers die – Nicholas Nickleby comes immediately to mind. And we’ve seen other brothers who take advantage of their sister’s love – Tom Gradgrind in particular. Charley is a mash-up of these two, taking his responsibility as seriously as Nicholas, but mishandling as terribly as Tom. Thank goodness Lizzie Hexam is more sure of herself than Louisa Gradgrind or her marriage to Bradley Headstone would have been just as miserable a one as Louisa’s.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So much wonderful insight! And YES, Headstone’s proposal even tops Darcy’s, Collins’s, and Guppy’s–the latter’s actually quite wonderful–as The Worst Marriage Proposals Ever!

LikeLike

Bradley Headstone! – the latest character in a long line of spurned lovers, of characters suffering from unrequited love, of characters who endeavor to control their unrequited love, of characters for whom jealousy grows from their unrequited love, who seek relief through revenge. Characters we have met who fall in to one or more of these categories include: Mrs Bardell (PP), Monks’ mother (OT), Smike, Fanny Squeers, and Mr Lillyvick, (NN), Dick Swiveller and the Single Gentleman (OCS), Simon Tappertit, Miss Miggs and Mr Haredale (BR), Tom Pinch, Charity Pecksniff, and Mr Moodle (MC), Mr Toots, Miss Tox, Major Bagstock, Mr Carker and Alice Marwood (DS), Uriah Heep, Jack Maldon, Ham, and Rosa Dartle (DC), Mr Guppy and Mr Boythorn (BH), Mr Harthouse and Mrs Sparsit (HT), Young John Chivery, Miss Wade and Miss Rugg (LD), Sydney Carton and Mr Stryver (ATTC), Miss Havisham, Pip, and Orlick (GE), and now Miss Peecher and Bradley Headstone, (what happens in The Mystery of Edwin Drood remains to be seen).

With these characters and their situations – the comic, the serious, and every thing in between – Dickens has taken us through a myriad of permutations of the unsuccessful and/or unrequited lover’s journey. Further, what began as a humorous situation involving a supporting character (Mr Pickwick’s mistaken proposal to Mrs Bardell) has evolved into a major plot point for a main character (Bradley Headstone’s passion for Lizzie).

Why this topic of unsuccessful and/or unrequited love should be of such import to Dickens has been discussed by many of his biographers, but I think John Kucich is most succinct:

“In [his fiction], Dickens is clearly working out his own troubled attitudes toward marriage, divorce, and adultery, and exploring the circumstances that may or may not permit the enlarging of one’s sexual experience.” (229, Repression in Victorian Fiction: Charlotte Brontë, George, Eliot, and Charles Dickens)

John Forster reports of Dickens lamenting (in 1857),

“Why is it, that as with poor David, a sense comes always crushing on me now, when I fall into low spirits, as of one happiness I have missed in life, and one friend and companion I have never made?” (Life of Charles Dickens, Vol III, Ch VII)

Referring back to David Copperfield, Ch 48 “Domestic”, wherein David reflects on his marriage to Dora, we understand the nature of the “one happiness . . . missed”:

“The old unhappy feeling pervaded my life. It was deepened, if it were changed at all; but it was as undefined as ever, and addressed me like a strain of sorrowful music faintly heard in the night. I loved my wife dearly, and I was happy; but the happiness I had vaguely anticipated, once, was not the happiness I enjoyed, and there was always something wanting.” (David Copperfield Ch 48)

For David, that “something” turns out to be Agnes Wickfield. For Dickens, finding that something wasn’t so easy.

C.G.L. Du Cann examines this quest, if you will, in his book, The Love-Lives of Charles Dickens (1961, Greenwood Press). Du Cann identifies 14 different women, including Dickens’s wife, with whom he (Dickens) was in love or at least with whom he was infatuated. Evidence that being in love or infatuated was, for Dickens, a rather common state Du Cann reports this anecdote:

“Of his ready susceptibility there was a family story – perhaps aprocyphal – that in his middle-age one of his young children, gazing with deep commiseration at his brooding parent . . . remarked to a visitor: ‘Look! poor Papa is in love again.” (17)

Yet other than his marriage to Catherine and his alleged affair with Ellen Ternan, with none of the women named by Du Cann did Dickens have a physical (sexual) relationship. All of these love affairs or infatuations were conducted as flirtations – some more serious or pointed than others – or existed only in the mind of Dickens – what Du Cann calls “spiritual adultery . . . adultery of the mind and heart”, which “can be as potently destructive as the physical”. (278) Dickens’s quest, conscious or unconscious, to find romantic and/or sexual happiness played a large part in his working himself to exhaustion and, some argue, premature death. And it is this quest which I believe he explores through the long list of characters and situations noted above.

LikeLiked by 2 people

So could we say Bradley Headstone is Charles Dickens on a really bad day?

LikeLike

Or maybe David Copperfield was his good twin (or innocent twin anyway) and Bradley Headstone was his evil twin?

LikeLike