Wherein we glance back at the second week of the #DickensClub reading of Oliver Twist; With General Memoranda, a summary of reading and discussion, and a look ahead to week three.

“I have saved you from being ill-used once: and I will again: and I do now…for those who would have fetched you, if I had not, would have been far more rough than me. I have promised for your being quiet and silent: if you are not, you will only do harm to yourself and me too: and perhaps be my death…”

Poor Oliver! After the first bit of true rest and recovery and care that is shown to him, he is instantly swept up again into the life of Fagin, Sikes, and their accomplices. He has found a compromised protector…will that be enough to save him?

General Mems

This past week, we’ve discussed the possibility of altering the reading schedule just enough to accommodate a week or two of a break in between each read. This would serve several purposes: to help some of the readers who are behind to catch up; for the purposes of more in-depth discussion; for the composition of special interest posts; to do a group watch of an adaptation of the book we’ve just completed. As far as the poll goes, the group is unanimous on the break, though at least one who is mostly here for the discussion likes it as is. So, before Boze and I rework the schedule, the only question remains…one week, or two? Thoughts? Please comment below…

If you’re counting, this coming week will be week 17 of the #DickensClub as a whole (and today Day 112), and the third week of Oliver Twist (our third read). Please feel free to comment below this post for the third week’s chapters, or to use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter.

No matter where you’re at in the reading process, a huge “thank you” for reading along with us! We’re forever grateful for shares and retweets from all! Including friends new and old, our marvelous Dickens Fellowship, Dr. Christian Lehmann, Dr. Pete Orford, and all of our Dickensian heroes, for helping to build our reading community. And a huge thank you to The Circumlocution Office for providing such an online resource for us!

We’d love to have new readers join us. If you’re interested: the schedule is in my intro post here, and my introduction to Oliver Twist can be found here. Boze’s most marvelous post on Fagin and antisemitism in Oliver Twist can be found here, and is an ongoing conversation. If you have been reading along with us but are not yet on the Member List, I would love to add you! Please feel free to message me here on the site, or on twitter.

Week Two Oliver Twist Summary (Chapters 12-22)

At the opening of Chapter 12, we finally have a little respite for poor Oliver, as he is taken care of at Mr. Brownlow’s lodgings by the kindly Mrs. Bedwin. There, Oliver is strangely affected by the mysterious portrait of a woman. Mr. Brownlow, too, is startled by the likeness between Oliver and this woman. Shortly after this scene, during which Oliver faints, the portrait is removed.

Fagin berates his apprentices, Charley and the Dodger, for coming back without Oliver. Fearful that Oliver is a liability, Fagin has Nancy look into it. She goes to the police station, pretending to be Oliver’s concerned sister, and find out that the kindly gentleman from the trial had taken Oliver to his own home in Pentonville, and she and a couple of the boys go in search of him.

Mr. Brownlow is visited by his grumpy and jaded friend, Mr. Grimwig, who is of the opinion that Oliver is not to be trusted. When an errand to Mr. Brownlow’s bookseller is needed requiring the delivery of expensive books and a five-pound note, Grimwig all but challenges Brownlow to send Oliver, who is very willing to prove himself and be useful. Brownlow does so. Nancy, however, with the assistance of Bill Sikes, re-kidnaps Oliver, pretends again (for the sake of the onlooking crowd) to be the concerned sister.

Shortly after, Nancy, who is already regretting her part in the whole scheme, comes to the defense of Oliver who is being threatened with a beating and stripping (in order to sell off his good clothes) by Fagin. We come to learn that Nancy, too, had been one of Fagin’s apprentices from when she was about half Oliver’s age; clearly, something about him moves her deeply, and brings out the maternal instincts.

Mr. Brownlow advertises a reward for any person who can bring him information on Oliver’s whereabouts; Mr. Bumble himself visits, and convinces Brownlow that Oliver is not to be trusted. And that gentleman, who has been disappointed in the past instances of misplaced trust, asks that Oliver’s name never be mentioned again by Mrs. Bedwin nor anyone else.

“‘Never let me hear the boy’s name again. I rang to tell you that. Never. Never, on any pretence, mind!…’

“Oliver’s heart sand within him, when he thought of his good kind friends; it was well for him that he could not know what they had heard, or it might have broken outright.”

Meanwhile, Fagin manipulates Oliver’s emotions and sense of reliance by first isolating and imprisoning him, and then bringing him into the company of the other boys, feeling that he will be grateful for any company rather than being alone, and thereby develop a sense of loyalty towards them. And his loyalty is tried when Fagin suggests him as a boy small enough to fit the bill for one who can fit into the window-frame of a house that Sikes intends to rob, along with his accomplices, Crackit and Barney.

” ‘Well, he is just the size I want,’ said Mr. Sikes, ruminating.

‘And will do everything you want, Bill, my dear…he can’t help himself. That is, if you frighten him enough.'”

Nancy encourages Oliver to see it through. In her private talk with Oliver, Nancy shows herself to be conflicted and compromised; Oliver realizes that “he had some power over the girl’s better feelings.”

“You can’t help yourself. I have tried hard for you, but all to no purpose. You are hedged round and round; and if ever you are to get loose from here, this is not the time.”

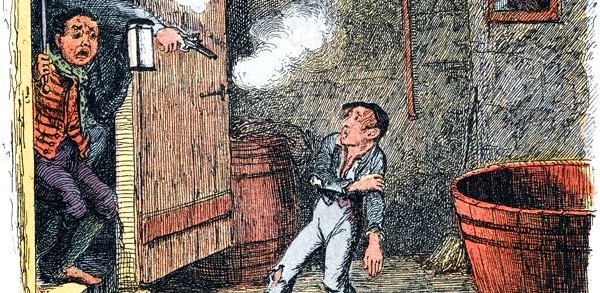

As Oliver realizes the part he is supposed to play and as Sikes lowers him into the house through the window, Oliver resolves that, instead of opening the street-side door for Sikes and his companions, he will instead risk death to run and warn the family; but they are already awake, and, finding Oliver trespassing, shoot him. Sikes lifts the bloodied child back through the window and they all flee the scene.

Discussion Wrap-Up

Engagement in Reading

Daniel and the Stationmaster got the conversation going this week, and the latter emphasized the amazing readability and engagement of Oliver, in spite of the darker tone which contrasts so strikingly from Pickwick:

And Steve remarked on the cliffhanger of Chapter 14’s ending:

Dickens’ Narrative Technique; Darkness and Light; Movement and Rest; Melodrama and Theatricality; Nancy

We’ve discussed, bringing us back to Pickwick, the “Heart of Darkness” within London and Society, as Lenny called it; Dickens’ social conscience, and the “moral conscience” alluded to by Daniel; the darkness and light within our characters ~ both so uniquely conflicted in Nancy.

It was difficult to “break up” this week’s themes, and the coherence of thought of these essays; each theme is so bound up in the others, and many revolve around the key moment in Chapter 20 when Nancy reveals to Oliver her own troubled psyche and conscience as she grapples with how to help him. This all connects to what we’ve discussed in the theater and melodrama in Dickens.

Most of these below are in “gallery mode”; click on each image to see the comment enlarged.

Boze, as a writer, focused on the narrative techniques employed by Dickens; how he draws us to sympathize with our characters and make each so unique. He reflects on Pullman’s point about the cinematic/visual quality of Dickens’ writing:

Boze H. comments

I added thoughts about the Pullman essay; Dickens’ theatricality and “preternatural energy”:

Rach M. comments

The Stationmaster, however, thinks the more visual media, however, can’t quite do justice to Dickens’ marvelous words:

The crucial scene in Chapter 20 begins as follows, with Nancy wanting to “put down the light” that hurts her eyes:

“Oliver raised the candle above his head: and looked towards the door. It was Nancy.

‘Put down the light,’ said the girl, turning away her head. ‘It hurts my eyes.’

Oliver saw that she was very pale, and gently inquired if she were ill. The girl threw herself into a chair, with her back towards him: and wrung her hands; but made no reply.

‘God forgive me!’ she cried after a while, ‘I never thought of this.’

‘Has anything happened?’ asked Oliver. ‘Can I help you? I will if I can. I will, indeed.’

She rocked herself to and fro; caught her throat; and, uttering a gurgling sound, gasped for breath.”

Chris focuses in on Nancy, Oliver’s unexpected protector, “a prostitute” who “had no doubt been a child prostitute” who is “also a battered woman and the victim of predatory, decidedly older, men.” Now, she is becoming “suddenly aware”:

Chris M. comments

Lenny agrees. Here’s the opening statement from his essay which I’ll put below in full:

“Extraordinary analysis, Chris. Nancy’s caught between the light and dark worlds–as we’ve been calling them throughout our discussion of Dickens, starting with the SKETCHES. And you do such a good job of pointing this out. Oliver in his goodness and innocent youth, obviously stands for the lighter end of the spectrum–should he not be completely and irrevocably drawn into the Fagin/Sykes milieu as the other boys have experienced.”

~Lenny H.

I started out discussing the themes of Movement versus Rest: the incessant and inhuman nature of the former here; the peace and beauty of the latter as Dickens so often conveys it. I then discuss the theatricality of Dickens, the strangeness of his imagination (Ackroyd), and my disagreement with Tomalin about Nancy:

Rach M. comments

Lenny challenges Tomalin’s idea from his own experience of such anxiety/panic attacks:

Lenny H. comments

But but beyond the realism, Lenny focuses in on the “progression” in the personalities of Oliver and Nancy, and how, in a way, they have changed places, as he has activated something long dormant in her, and he takes on a more adult role:

Lenny H. comments

Steve focuses in in Chapter 17 and how “Dickens already was becoming adept at pulling heart strings and going straight for the jugular”:

Chris asks the question, on Nancy:

“How far will Nancy go to protect Oliver? Is it even really Oliver she is protecting? Or is she motivated by something – someone – else?”

~Chris M.

Anima and Archetypes

We’re still zooming in on Chapter 20, and Lenny gives us a Jungian analysis of the role reversals, the activation of what is dormant within our characters, and how Nancy, “by summoning (up) and protecting Oliver (as archetype and person), she is beginning to protect and ‘save’ a part of her OWN ‘self,’ the child segment that, before she comes into the novel , she’s ‘split off’ and buried within her unconscious”:

Dickens’ Romanticism

For those who weren’t reading the Ackroyd piece that Chris shared (due to spoilers), I shared a passage that was particularly striking:

“…his whole conception of Oliver Twist seems to have changed. He recreated Rose Maylie in the image of his dead sister-in-law, of course, but even before that happy resurrection much of the topical and polemical intent of the novel is abandoned and Dickens introduces a slower, more melancholy note which comes to pervade most of its subsequent pages. In fact it can be said that Dickens now introduces something of English Romantic poetry—Wordsworthian, in particular—into his fiction, and it has often been claimed that it is precisely this new presence which marks the true distinction of Oliver Twist. Dickens brings into his novel ideas of innate beauty, of childhood innocence, of some previous state of blessedness from which we come and to which we may eventually return. It is in these passages that his prose seems instinctively to move with poetic cadence and diction. It is as if the death of Mary Hogarth had broken him open, and the real music of his being had been released—and how powerful it becomes when it is aligned both with his helpless memories of his own childhood and with the greatest extant tradition in English poetry.”

~Peter Ackroyd

Lenny wrote a beautiful piece on this topic, focusing in on Wordsworth’s idea that “The Child is father of the Man”:

Lenny H. comments

A Look-ahead to Week Three of Oliver Twist (26 April-2 May)

This week, we’ll be reading Chapters 23-34, which constitute the monthly numbers XI-XV, published Feb-June 1838.

You can read the text in full at The Circumlocution Office if you prefer the online format or don’t have a copy. There are also a number of places (including Gutenberg) where it can be downloaded for free.

I love the new layout – easier to read!

Maura K. Phelan Green Light Literary + Media 781.706.3380 maura@greenlightlit.com http://www.greenlightlit.com

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Awesome! So glad, Maura. Still trying to work out how to best incorporate all of these amazing comments on the week’s reads; the current screenshot/gallery mode still seems less-than-ideal, but if I were to copy/paste all of the amazing “essays” here, it’d look dauntingly long! 🙂 And I hate leaving out things, when the comments have been so rich. 🖤

LikeLiked by 1 person

A+ Amiga!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aww, thanks, Lenny!!!!

LikeLike

Greetings!

Yes, the gallery juxtaposition of related posts/comments is very readable and intelligible.

Thanks much, Dickensian Wren, for your diligent and careful way of showcasing the “graduate seminar” on Dickens we are experiencing. Truly, the level of exchange is extraordinarily rich and enriching.

A couple of thoughts to share.

1. Sabbath rest: It makes great sense that we need and benefit from rest from the “grind” of daily responsibilities. Thank goodness, most of us can avail ourselves of rest intermittently and on one designated day of the week. The moments when Oliver can rest are those in which there is order, peace, benevolence, kindness, care. Because of the constant and cruel pressure on him, we experience his rest expansively.

2. Shameless emotional manipulation: I delighted in the observation about Dickens’ “cheap, mercenary, and masterful” ways of manipulating us, his readers and fellow pilgrims. I imagine a dev’lish twinkle in his eye as he creates a heart-wrenching scene or leaves us at the brink of a literary cliff.

3. Growth through relationships: We all learn and grow through relationships, best through relationships that are caring and kind. We also learn from the relationships that harm us, if we have the bandwidth to reflect on them and extract the lessons. Similarly, it seems that (for example) Oliver and Nancy are helping one another become more fully who they are through their caring relationship–awakening, as noted, the “anima” capacity for nurturance and caring. Their effect is symbiotic–mutually life-giving.

Let’s keep learning and growing in this “master class” on Dickens!

Daniel

LikeLiked by 4 people

I didn’t have time to prepare a full comment this week because I was reading a good book, but I loved the digression at the beginning of chapter seventeen about the alteration of tragic and comic scenes in works written for the stage. “It is the custom on the stage, in all good murderous melodramas, to present the tragic and the comic scenes, in as regular alteration, as the layers of red and white in a side of streaky bacon. The hero sinks upon his straw bed, weighed down by fetters and misfortunes; in the next scene, his faithful but unconscious squire regales the audience with a comic song.” Last week I noted the use of this technique in Pickwick, so it’s fascinating to see Dickens here explicitly acknowledging its use. It shows that he was fully conscious of the tricks of his craft, but also seems to affirm what Philip Pullman said in his essay, that the secret of Dickens’ dramatic gifts as a novelist may have sprung from his love of the theatre. He absorbed all the stage melodramas of his era and repurposed them in the furnace of his genius. It also makes me wish that Dickens had written a longer essay or even a book on the craft of writing. Perhaps one of us might venture back in time and induce him to write such a book?

Reading Dickens’ descriptions of the various inns and courts – “At length they turned into a filthy narrow street, nearly full of old-clothes shops” – I was struck by the fact that Dickens, with his encyclopedic knowledge of London, would have been able to fully envision the location of each incident in the novel, even when the streets and alleys aren’t explicitly named. In 2010 it was discovered that as a boy he had lived just down the street from the Cleveland Street Workhouse, which has led to speculation that he had this workhouse in mind when he was writing Oliver. This is important because I think we tend to picture generic locations of ill repute when we’re reading, whereas Dickens was writing about specific places which he could see in his mind’s eye like a vision. Such were his powers of imagination that the fictional London became as real to him as the real London of his nightly rambles – recall the sad incident on the final night of his life when he was so absorbed in writing a scene from Drood that he failed to hear his own son calling his name. He knew these streets so intimately that he was able to conjure them on the page with startling force and vividness. There’s an immediacy to his writing in this book that hasn’t been dimmed by the passage of years.

LikeLiked by 3 people

LOVE the focus on the theatrical/melodramatic here. I’ll volunteer to time-travel; only, not sure whether I’ll be seen again if I manage it…

Darn those *other* books that get in the way of Dickens! 🙂 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yep–nasty other books! Ought be a law….😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Haha, agreed, Lenny! Nasty little monsters 😂

(As I just add to my pile with a stop at the library after work, AND a new Peter Ackroyd read, AND…)

sigh…

LikeLiked by 2 people

OMG! New glasses?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Of all the characters in the book, Dr. Losberne is the one I take as my role model. I love that he’s more realistic about the possibility that Oliver could be no good than Rose and Mrs. Maylie are, but he still helps him. Plus, he’s really funny. “He has not been shaved very recently, but he don’t look at all ferocious notwithstanding.”

The chapter about everyone worrying about Rose may be kind of overindulgent, but I love the part where Oliver feels that nothing tragic could happen on a nice sunny day and then sees the funeral mourners. That feels very real, maybe like something Dickens experienced himself.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I find it strange that Oliver would question that a young person – Rose – could/can die after all his experience at the baby farm, workhouse, Sowerberry’s, Fagins’s den, heck, even his own very young mother! But perhaps because he is now experiencing something completely new and foreign to him – life in an ideal environment – an idyll – he has difficulty imagining that anything that had been part of his old horrid life – such as death – could ever be a part of this Eden.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Perhaps it doesn’t quite make sense for Oliver’s character (I kind of think it does since he’s so seldom known people quite like the Maylies), but that’s more evidence that it reflects a real experience had by Dickens.

I think the reason Dickens included that chapter, apart from bringing Oliver and Monks together, was to remind readers that tragedy can befall anyone, even good people in good circumstances.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We’ve spoken at some length about Nancy’s key role in Chapter 20, as she “relates” to Oliver her desire to help and care for him–an important moment for her as she begins to release the nurturing part of her personality that has long been embedded within her shadow. And, of course, we see how it is Oliver that has activated this key element in her unconscious psyche. On the other hand, a more exotic personification of the potential within her shadow (that is becoming less dormant and more prominent) is the first full-blown portrait we have of Rose in Chapter 29. Here Rose is shown to be radically idealized as much as Nancy has been shown to be radically corrupted–all but ruined in her capacity as thief and prostitute while governed by the evil doings of Fagin and Sikes. Seemingly, then, they operate in the novel as polar opposites to one another, while, interestingly enough they are probably about the same age. Here is our first sight of the tender and beautiful Rose:

“The younger lady was in the lovely bloom and spring-time of womanhood; at that age, when, if ever angels be for God’s good purposes enthroned in mortal forms, they may be, without impiety, supposed to abide in such as hers.

She was not past seventeen. Cast in so slight and exquisite a mould; so mild and gentle; so pure and beautiful; that earth seemed not her element, nor its rough creatures her fit companions. The very intelligence that shone in her deep blue eye, and was stamped upon her noble head, seemed scarcely of her age, or of the world; and yet the changing expression of sweetness and good humour, the thousand lights that played about the face, and left no shadow there;”

This stunning “portrait” is, we know, diametrically opposed to the “picture” we’ve had of Nancy up to this time. Yet, in some ways, they are kindred soles, “sisters” of a kind, who both have similar aims when it comes to their young “progeny” Oliver. They have definitely become teenage “mother” figures to their pure and innocent son.

Yet, the description of Rose above is somewhat misleading, as she, too, bears a shadow as long and as demanding as that borne by Nancy. Rose is, in spite of the final misleading words of the above paragraph (“left no shadow there”) laboring under the notion that she, too, is in some regards, a “fallen” woman, and that fear will carry over into her relationship with her paramour Harry. Both she and Nancy have been “marked” by past events and try their best to stand up under their mutual disgusts that they have for themselves. Rose’s shadow is that of renunciation (of self, of Harry); Nancy’s is that of potential emancipation and salvation. One might say, in a Jungian sense, each of these women operate as one another’s shadow!

But I want to go back, a bit, to a much earlier chapter (12) where there is another ACTUAL portrait which lies above Oliver as he is convalescing in the Bedroom at Mr. Brownlow’s. Again, the painting is of a young woman who, unbeknownst to Oliver at the time, is looking down on him. In his sleepy declaration to Mrs. Bedwin, he relates his thoughts that his mother has been probably looking down upon him during his illness:

“With those words, the old lady very gently placed Oliver’s head upon the pillow; and, smoothing back his hair from his forehead, looked so kindly and loving in his face, that he could not help placing his little withered hand in hers, and drawing it round his neck.

‘Save us!’ said the old lady, with tears in her eyes. ‘What a grateful little dear it is. Pretty creetur! What would his mother feel if she had sat by him as I have, and could see him now!’

‘Perhaps she does see me,’ whispered Oliver, folding his hands together; ‘perhaps she has sat by me. I almost feel as if she had.’

‘That was the fever, my dear,’ said the old lady mildly.

‘I suppose it was,’ replied Oliver, ‘because heaven is a long way off; and they are too happy there, to come down to the bedside of a poor boy. But if she knew I was ill, she must have pitied me, even there; for she was very ill herself before she died.'”

Naturally, the nearest “mother figure’ here is Mr. Brownlow’s housekeeper, but the figurative “mother” to which Oliver refers is a figment of his illness and sleep-induced mind. Yet the foreshadowing is, above all, poignant and striking. Not only has he invoked the very image of his mother, but is also casting forward to the two young women who will be his saviors from the evils of Monk and Fagin.

Slightly later, the novel demonstrates how “real” Oliver’s dream has become:

“‘Are you fond of pictures, dear?’ inquired the old lady, seeing that Oliver had fixed his eyes, most intently, on a portrait which hung against the wall; just opposite his chair.

‘I don’t quite know, ma’am,’ said Oliver, without taking his eyes from the canvas; ‘I have seen so few that I hardly know. What a beautiful, mild face that lady’s is!’

‘Ah!’ said the old lady, ‘painters always make ladies out prettier than they are, or they wouldn’t get any custom, child. The man that invented the machine for taking likenesses might have known that would never succeed; it’s a deal too honest. A deal,’ said the old lady, laughing very heartily at her own acuteness.

‘Is—is that a likeness, ma’am?’ said Oliver.

‘Yes,’ said the old lady, looking up for a moment from the broth; ‘that’s a portrait.’

‘Whose, ma’am?’ asked Oliver.

‘Why, really, my dear, I don’t know,’ answered the old lady in a good-humoured manner. ‘It’s not a likeness of anybody that you or I know, I expect. It seems to strike your fancy, dear.’

‘It is so pretty,’ replied Oliver.

‘Why, sure you’re not afraid of it?’ said the old lady: observing in great surprise, the look of awe with which the child regarded the painting.

‘Oh no, no,’ returned Oliver quickly; ‘but the eyes look so sorrowful; and where I sit, they seem fixed upon me. It makes my heart beat,’ added Oliver in a low voice, ‘as if it was alive, and wanted to speak to me, but couldn’t.’”

Oh my! The novel has presented, in a hugely complex manner, a crucial image that, of course, mirrors that of our first sight of the magnificently beautiful and sweet Rose. Oliver remarks, excitedly, “what a beautiful, mild face that lady is…..” His words, the earlier description of Rose, our discussion of Nancy, she and Rose’s respective shadows, are ALL contained in this portrait that, Mr. Brownlow will notice, is exactly the likeness that Oliver presents to him. Yes, there is a mystery here, the novel will move forward, by stops and starts and stops, to present and solve it, but these images of young women in their various “postures” are excruciatingly indelible and persist as the novel progresses.

LikeLiked by 2 people

“The Burglary” goes bad and Oliver is shot and falls unconscious as he is carried away from the scene by Bill – and we are left hanging for five more chapters! Dickens, the master of cliffhangers!

In the meantime we are taken back to the workhouse where Mr Bumble seeks to enhance his position by marrying Mrs Corney, the Workhouse matron, and by being himself promoted to Master of the Workhouse – thus pooling their resources. Mrs Corney is of the same mind and we can only shudder for the unfortunate poor who will be under their care. But something isn’t quite right in this relationship. I’m taken back to Mr Tony Weller’s warning to beware of “widders”. Mrs Corney may have property in the form of teaspoons, sugar tongs & furniture, but she also has a secret she is unwilling to share until “one of these days, – after we’re married”. And while she and Mr Bumble are cut of the same pattern, she is decidedly cut of a tougher cloth than he. She complains of her own ill-usage and inconvenience when called to do her duty as Matron to visit the dying Old Sally; Mr Bumble, on the other hand, was ever so slightly affected by “Oliver’s piteous and helpless look” way back in Chapter 4 when he walked with Oliver to Mr Sowerberry’s. That moment in Chapter 4 creates a chink in Mr Bumble’s armor which some critics see as “an astonishing false note” which “is so out of key with all we know about him” (Carey 68), while others see it as creating a more sympathetic Mr Bumble (Kincaid 62). Why we should be sympathetic to him remains to be seen.

Back to Oliver, we find he has once again ridden the rollercoaster down, down, down, passed out and awaken in Eden! Left in the ditch by Sikes, he regains consciousness enough to drag himself to the very doorstep of the ill-fated burglary and, more importantly, to everything he ever wished for. And, as with his earlier taste of Eden, he is accepted on his story and looks alone. Regarding his story – On its face it seems farfetched especially in light of the two false alarms he raises. The first being his seeing the house where Sikes took him, which apparently isn’t the house because it is so drastically changed. The second is when he wakes to find Fagin & Monks staring at him through his open window, and then they mysteriously and completely disappear. Nonetheless, Oliver’s goodness and innocence shines through by virtue of his manners and his physiognomy. Toby Crackit’s prediction rings true – “His mug is a fortin’ to him.” We’ve already seen how his face secured him a place of prominence at Mr Sowerberry’s – his melancholy face made him a terrific mute for children’s funerals, earning him the ill-will of Noah Claypole, which led to his running away and meeting up with the Dodger and Fagin’s gang. And we’ve seen that his face is very like the portrait in Mrs Bedwin’s room at Mr Brownlow’s house. So how else will his face be significant? And there’s something more to Oliver – at least to Fagin who tells the drunken Nancy he’d as soon give up Bill and his gang to get Oliver safely back because Oliver is “worth hundreds of pounds” to him. What can this mean?

It is at this point that we are introduced to a new character, Monks, “a dark figure” who emerges from the shadows and glides up to Fagin “unperceived”. Monks wants Oliver – or rather, wants him corrupted. But why?

Perhaps Monks may get his wish, for the Bow-street Officers arrive at Chertsey to investigate the attempted burglary and to question the boy. Mr Losberne, however, manages to cover-up Oliver’s involvement by virtue of the simpleness of Mr Giles and Mr Brittles, and the Bow-street Officers, too. And so Oliver can remain happy in his little Eden. Until, that is, Rose droops and almost dies. A check upon happiness, but one that is soon lifted. Rose survives. Her illness brings another new character, Harry Maylie a love interest, and another mystery – there is a “stain” upon Rose regarding “her doubtful birth” – what can this mean?

So many mysteries – cliffhangers – to keep the reading public coming back for more!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I kept stopping to write down the awe-inspiring declarations of love that Mr. Bumble made to Mrs. Corney ~ it positively rivals Guppy, Headstone, Collins, or Darcy for marriage proposals! “Coals, candles, and house-rent free…Oh Mrs. Corney, what a Angel you are!…my fascinator…Such porochial perfection!”

I love the particularly Gothic turn Oliver takes once the mysterious Monks is introduced, along with his almost supernaturally haunted paranoia, and the image of the woman that the believes he sees. It sounds like something **right out of** Victorian stage melodrama (and I’ve read quite a few Victorian stage melodramas): “The shadow! I saw the shadow of a woman, in a cloak and bonnet, pass along the wainscot like a breath!”

“The candle, wasted by the draught, was standing where it had been placed. It showed them only the empty staircase, and their own white faces. They listened intently; but a profound silence reigned throughout the house….They looked into all the rooms; they were cold, bare, and empty. They descended into the passage, and thence into the cellars below. The green damp hung upon the low walls; and the tracks of the snail and slug glistened in the light of the candle; but all was still as death.”

I’ll catch up on reading comments and writing more tomorrow once I’m home from my long shift, but I just had to mention these things which occurred to me during the rainy, gothic, witching hours of the night! 😊

LikeLiked by 2 people

To add to my earlier comments on the Gothic tone that Oliver took on with the introduction of Monks, I was really compelled to go back to some things I alluded to in the Introduction to Oliver, and which seems to be such a recurring theme for Dickens: the significance of Memory, and Rest.

But first, I’d forgotten just how strongly Rose was clearly Mary Hogarth, even in age and in her goodness. and angelic qualities. Dickens is writing out his grief and his love for Mary here:

“She was not past seventeen. Cast in so slight and exquisite a mould; so mild and gentle; so pure and beautiful; that earth seemed not her element, nor its rough creatures her fit companions. The very intelligence that shone in her deep blue eye, and was stamped upon her noble head, seemed scarcely of her age or of the world; and yet the changing expression of sweetness and good humor, the thousand lights that played about the face, and left no shadow there; above all, the smile, the cheerful, happy smile, were made for Home, and fireside peace and happiness.”

It almost feels like the introduction of Rose’s illness in Chapter 33 is a way of Dickens dealing with that of Mary’s, and trying to write out a better end for it, to replace the real one.

Memory as it calls out to us from Nature (“the rose and honeysuckle clung to the cottage walls; the ivy crept round the trunks of the trees; and the garden-flowers perfumed the air with delicious odors”) and connects us to our childhood; to half-remembered, buried recollections of the kind of state we lived in before the introduction, or intrusion, of society, commerce and industry. Before we were forced into unnatural roles as beings that did nothing but work to survive.

And Memory is connected, in a more benevolent way, to death: I don’t think it is by chance that the Maylies’ country cottage is “hard by” a little churchyard, whose freshness and greenness make Oliver wish his own mother could have been buried in such a place.

And that this sense of the religious significance of Memory comes up so strikingly in OT once Oliver has gone to the country with the Maylies, is significant: Nature connects us to our state of being before we were introduced to the harshness of the world and of its work. Here’s where Dickens becomes less the satirical social critic, and more of the Romantic. There is a kind of Rousseauean ideal here: Memory and happiness and goodness—and learning, too, as Oliver learns to read and write more adeptly here, and to enjoy Stories, and Music—are connected to Nature rather than to the city; connected to our state of being before we were brought into the rough contact with the world and of having to scrape by in it. This more corrupted state is, I think, the City: it is the London that Oliver knows.

Our better memories are connected to an early sense of Rest, and of being loved for our own sake, aside from what we can give or offer—we’re almost introduced to a Memory of, we might say, Eden, or of something that predates our existence on earth:

“The memories which peaceful country scenes call up, are not of this world, nor of its thoughts and hopes. Their gentle influence may teach us how to weave fresh garlands for the graves of those we loved: may purify our thoughts, and bear down before it old enmity and hatred; but beneath all this, there lingers, in the least reflective mind, a vague and half-formed consciousness of having held such feelings long before [childhood? Or a state predating birth?], in some remote and distant time, which calls up solemn thoughts of distant times to come, and bends down pride and worldliness beneath it.”

So, Memory is connected to Nature, and to our natural state, and to Rest. I thought it was interesting too that Dickens brings up Sunday in particular, which of course has been for many a day of rest: “And when Sunday came, how differently the day was spent, from any way in which he had ever spent it yet!” What a different tone, from, say, Arthur Clennam’s take on Sundays in Little Dorrit, in which he was haunted and depressed by the dismal church bells on that day, and by something dark and lonely: the cold, work-oriented, dismal religion of Mrs. Clennam, his mother.

Is anyone else ready to move to an ivy-laden cottage in the countryside? I sure am!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Just a quick thought – The question of Nature versus Nurture is also here – Oliver clearly represents Nature over Nurture because he refuses to be corrupted by the harshness and corruption that has surrounded him since birth.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Absolutely! Good point Chris 👍

LikeLike

Wow, Chris and Rach, you two are on a roll here! So much is going on in your respective commentaries, that my mind is just beset with a whirl of ideas. Let me just add something to the idea of memory that has always struck me with its forceful and “just” meaning. Since I’ve always admired Wordsworth, his poetry and his thoughts about poetry–which are many–then you know where I’m coming from. Here’s one of the most famous quotes from this 1802 “Preface to Lyrical Ballads” that is so apropos to Rach’s discourse on memory in her thoughts about Oliver:

“I have said that Poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquillity: the emotion is contemplated till by a species of reaction the tranquillity gradually disappears, and an emotion, kindred to that which was before the subject of contemplation, is gradually produced, and does itself actually exist in the mind. In this mood successful composition generally begins, and in a mood similar to this it is carried on; but the emotion, of whatever kind and in whatever degree, from various causes is qualified by various pleasures, so that in describing any passions whatsoever, which are voluntarily described, the mind will upon the whole be in a state of enjoyment.”

The entire quote is significant in that it captures the emotion endowed by Dickens in his creation of OLIVER, but the one part of the quote that stands out for me that Rach points to in her remarks is the famous phrase “”Poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings” taking “its origin from emotion recollected in tranquillity.” Rach’s idea, about the “significance of Memory, and Rest” seems to parallel exactly what Wordsworth is saying here and throughout the “Preface” about the importance of memory and the idea of composing from a position of tranquility.

But without going into any depth about the nature of innocence and the environment that fosters it, I must say that again and again in Wordsworth’s “Preface,” there are MANY instances where this Romantic Poet discusses the earlier phases of one’s existence (the child’s) and how important that is in manifesting one’s growth. In his “The Prelude, Or Growth of a Poet’s Mind” the poet puts into action the theories he proposes (from his own experiences) , the various aspects of his childhood growing up and communing with nature. Again, Rach writes thoughts that run parallel to Wordsworth’s monumental poem:

“So, Memory is connected to Nature, and to our natural state, and to Rest.”

And this prescient remark coupled with her quote from OLIVER , “The memories which peaceful country scenes call up….” pretty much put Dickens–in this phase of the novel–solidly in the Wordsworth camp!

By the way, if you have time, all of you, read Wordsworth” “Preface” and at least the earlier segments of his great poem “The Prelude.” The parallels with Dickens and his view of children are significant!

But to get, briefly, to Chris’ comment regarding the astounding gap between Oliver’s being left for dead at the end of Chapter 22, and the narrative again taking up Oliver’s fate at the beginning of Chapter 28; there is, again, much going on that is very relevant to the elements of the novel going forward. As Chris points out Chapter 23 is devoted to the flirtation between Bumble and Mrs. Corney–and illustrates the greedy motives that are driving Bumble’s actions. But this “romancing” is interrupted by the need for Mrs. Corney to visit the beside of the dying colleague–who, in the next chapter, relates more crucial information for the mystery plot that is rapidly becoming the heart of the novel. Chapter 25 is the admission to Fagin that the Robbery has been bungled and Oliver may well be dead, and we see the wild response to this relation by Fagin. Chapters 26 and 27 follow up on the earlier chapters with more mysterious sets of ideas that create in more depth the “mysteries” to which Chris refers and which seem destined by the writer to seduce the reader to the max, as the reader must by this time, feel totally frustrated by the gaps between Chapter 22 and 28. But also, immensely INTRIGUED.

All these happenings move the novel forward in a kind of zig zag manner and, it seems to me, show the immense growth by Dickens in his recognition of how to build a novel that is both complex and filled with various lines of narration, The term subplots comes to mind, something that we begin to see near the end of PICKWICK but which is never fully manifested in that narrative with progresses mainly in a straight line. But here, in OLIVER, we see many plotlines developing, so that the novelist gives us an optimal sense of SIMUJLTANEITY–multiple stories happening at once–as we experience it. And ALL of these units of narration seem complete in and of themselves–but they will be continued at some point, and be brought together into the main “PLOT” during and toward the conclusion of the novel.

Those of you who have read tons more of Dickens than I, probably take this kind of plot development for granted, as it manifests itself in the future novels. But I’m wondering, however, if this more creative narrative facility, as Dickens has developed in OLIVER, will be the touchstone for his further novels?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lenny, what marvelous thoughts!!! I am eager to go back to the Wordsworth before we conclude with Oliver, and there is SO much here that I’ll be reflecting on today and in the coming weeks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, Rach! It’s just mind-blowing stuff, so much going on in this very early novel. OMG. We are just starting out but making a lot of progress with respect to the earliest Dickens. What magnificent treasures still await, eh? Loved your reflection back to the points of interest you set forth in your intro to OLIVER. Those thoughts are invaluable and very much worth considering…. Thanks so much!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lenny & Others – Dickens was SO masterful at handling the so-called multi-plot novel! The various plots in “Oliver Twist” are really nothing compared to what’s in store for us in later – longer – novels! How he ever, first, came up with them all and, second, kept track of them all and, third, tied them all together in the end (as he always does) always fascinates me!

And, I’m looking for a copy of Wordsworth’s Preface – thanks for the information & suggestion. I very much look forward to reading it – beyond the 70 lines provided!

LikeLiked by 2 people

OK Rach: just as a teaser, here are the first 70 lines of THE PRELUDE:

BOOK FIRST.

INTRODUCTION—CHILDHOOD AND SCHOOL-TIME.

O there is blessing in this gentle breeze,

A visitant that while it fans my cheek

Doth seem half-conscious of the joy it brings

From the green fields, and from yon azure sky.

Whate’er its mission, the soft breeze can come

To none more grateful than to me; escaped

From the vast city, where I long had pined

A discontented sojourner: now free,

Free as a bird to settle where I will.

What dwelling shall receive me? in what vale

Shall be my harbour? underneath what grove

Shall I take up my home? and what clear stream

Shall with its murmur lull me into rest?

The earth is all before me. With a heart

Joyous, nor scared at its own liberty,

I look about; and should the chosen guide

Be nothing better than a wandering cloud,

I cannot miss my way. I breathe again!

Trances of thought and mountings of the mind

Come fast upon me: it is shaken off,

That burthen of my own unnatural self,

The heavy weight of many a weary day

Not mine, and such as were not made for me.

Long months of peace (if such bold word accord

With any promises of human life),

Long months of ease and undisturbed delight

Are mine in prospect; whither shall I turn,

By road or pathway, or through trackless field,

Up hill or down, or shall some floating thing

Upon the river point me out my course?

Dear Liberty! Yet what would it avail

But for a gift that consecrates the joy?

For I, methought, while the sweet breath of heaven

Was blowing on my body, felt within

A correspondent breeze, that gently moved

With quickening virtue, but is now become

A tempest, a redundant energy,

Vexing its own creation. Thanks to both,

And their congenial powers, that, while they join

In breaking up a long-continued frost,

Bring with them vernal promises, the hope

Of active days urged on by flying hours,—

Days of sweet leisure, taxed with patient thought

Abstruse, nor wanting punctual service high,

Matins and vespers of harmonious verse!

Thus far, Friend! did I, not used to make

A present joy the matter of a song,

Pour forth that day my soul in measured strains

That would not be forgotten, and are here

Recorded: to the open fields I told

A prophecy: poetic numbers came

Spontaneously to clothe in priestly robe

A renovated spirit singled out,

Such hope was mine, for holy services.

My own voice cheered me, and, far more, the mind’s

Internal echo of the imperfect sound;

To both I listened, drawing from them both

A cheerful confidence in things to come.

Content and not unwilling now to give

A respite to this passion, I paced on

With brisk and eager steps; and came, at length,

To a green shady place, where down I sate

Beneath a tree, slackening my thoughts by choice,

And settling into gentler happiness.

‘Twas autumn, and a clear and placid day,

With warmth, as much as needed, from a sun

Two hours declined towards the west; a day

With silver clouds, and sunshine on the grass,

And in the sheltered and the sheltering grove

A perfect stillness. Many were the thoughts

Encouraged and dismissed, till choice was made

Of a known Vale, whither my feet should turn,

Nor rest till they had reached the very door

Of the one cottage which methought I saw.

No picture of mere memory ever looked

So fair; and while upon the fancied scene

I gazed with growing love, a higher power

Than Fancy gave assurance of some work

Of glory there forthwith to be begun,

LikeLiked by 1 person