Part One

“Reading through a writer’s entire oeuvre one is often struck by repetitive patterns. These patterns . . . assume their full significance only as they emerge in work after work. Encountered in a single work, such patterns are likely to seem topical or idiosyncratic. Encountered in book after book, however, they suggest a deeper significance: they suggest that they embody the author’s most profound hopes and fears. This is another way of saying that such repeated motifs are coterminous with the author’s chief concerns and whit his way of viewing the world; it also follows that such patterns can be used reflexively to provide fresh insight into his writings. With a pattern firmly in mind we can go back, reread a work, and assess it afresh. Sometimes we can do more: we can explain aberrations in constructions or responses or relationships that baffled us before.” (Stone 1)

Beginning with the mistaken marriage proposal of Mr Pickwick by Mrs Bardell which “supplies a plot-interest which continues to the end of the novel” (Butt &Tillotson 70-72), and continuing through and including the obsessive stalking in “The Mystery of Edwin Drood” (identities withheld to avoid spoiler), the foundation for major plot lines of all Dickens’s novels can be traced to amorous relationships, the majority of which are failures.

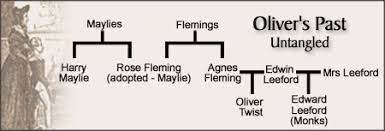

In “Oliver Twist”, each of the seven amorous relationships is influential, in varying degrees, to the development and/or resolution of the plot. Only one – Rose & Harry – can be considered truly successful; of the other six – Charlotte & Noah, Mr Bumble & Mrs Corney, Mr Brownlow & Miss Leeford, Nancy & Bill, Agnes Fleming & Edwin Leeford, and Edwin Leeford & Monks’ mother – Charlotte & Noah’s could be considered successful because they seem to get along though it’s far from a healthy relationship, while the rest all fail. I’ve traced these relationships and their influences on the plot as the beginning of an exploration of Dickens’s use of this motif through his novels, which I hope to continue as we read on. This discussion is, of course, purely subjective and open to further discussion.

Rose & Harry’s relationship is a bit of fluff, the requisite love story added to juice up the novel. Rose was added to give Dickens an outlet for his grief over the loss of his sister-in-law, Mary Hogarth, whose sudden death, almost exactly one year prior Rose’s creation, had a profound effect upon Dickens and his writing. (This is a story for another post.) Harry was added to give Rose a love interest (Monod 136). These characters and this relationship could easily be excised from the novel with just a bit of reworking to replace their contributions.

Be that as it may, Rose and Harry each has a role to play aside from being lovers. Harry’s role is to be Mr Brownlow’s “good friend” who “makes inquiries on the spot” about Monks, and most likely also about Fagin and the Gang, and then to lead the mob on his horse in pursuit of Bill (Ch 49 & 50). Rose is “meant to embody purity, innocence, beauty, and joy” (Monod 134). She is a mirror to Nancy for Nancy and the reader to see what she could/should have been. Rose also provides some rounding for her sister, Agnes (Oliver’s mother) – because we know Rose, we can extrapolate that Agnes wasn’t a bad girl, rather she was just a simple girl who trusted too much (Ch 49). Rose’s most important function is to meet with Nancy and then put the wheels of the novel’s resolution in motion. As I mentioned an earlier post, for all her sentimental sweetness, Rose is pretty level headed and in a relatively calm manner she thinks through the Nancy-Oliver situation and determines the best course of action. She actively enlists the help of the rediscovered Mr Brownlow and they draw up a plan of action which saves Oliver, discovers the villains and brings them to justice. Through the exposure of Monks’ plot, Rose’s true identity, like that of Oliver, is established. There is no longer a “blight” on her name, she IS as pure as she appears, and thus she is socially acceptable and worthy to be Harry’s wife. Kudos to Harry for wanting to marry Rose regardless of her “acceptability”, for caring more for her as a person than for what Society thinks!

The Charlotte & Noah relationship is a mirror to the Nancy & Bill relationship. Charlotte’s love and devotion to Noah reinforces the notion that a lower class woman can love a man who appears to be completely unworthy of being loved. Charlotte is unable to see that Noah treats her badly or that the things he has her do put her in a compromised position. Rather than worrying about being caught in possession of the money she stole for Noah from Mr Sowerberry, Charlotte is gratified because Noah “trusted in me, and let me carry it like a dear” (Ch 42). Charlotte is happiest when she can make Noah happy, whether it’s by feeding him oysters – “I like to see you eat ’em, Noah dear, better than eating ’em myself.” (Ch 27) – or otherwise doing his bidding – says Noah, “‘Why, you yourself are worth fifty women; I never see such a precious sly and deceitful creetur as yer can be when I let yer.’ ‘Lor, how nice it is to hear yer say so!’ exclaimed Charlotte, imprinting a kiss upon his ugly face.’” (Ch 42)

In response to contemporary readers and critics who “thought the character of Nancy improbable”, Dickens responded in his insistent 1841 Preface: “It is useless to discuss whether the conduct and character of the girl seems natural or unnatural, probable or improbable, right or wrong. IT IS TRUE” (emphasis in original). This statement about Nancy applies by extension to Charlotte and to all such “low” women. Indeed, I’m sure there were/are many women of the upper classes who gave/give their hearts to totally unworthy men – but that’s another essay.

More pointedly to the plot, Noah’s treatment of Charlotte shows us what a consummate weasel he is and the lengths (depths) he will go to to protect himself. He is as adept at arranging matters such that if caught Charlotte will be, literally & figuratively, left holding the bag, as he is at expending as little energy as possible for the most gain (see Ch 42). He is all too willing to be a spy, if it pays well and isn’t too risky as he does for Fagin which leads to Nancy’s murder and the exposure of the Gang (Ch 43 & 44). True to form, Noah “receiv[es] a free pardon from the crown in consequence of being admitted approver against” Fagin, and he and Charlotte “settle into business as . . . informer[s]” (Ch 53).

In contrast to the “lascivious” relations of Noah and Charlotte, “we are filled not with disgust but with trepidation for the wretched Bumble, foreseeing, as he cannot, what is in store for him when he wins Mrs. Corney’s hand” (Carey, 68). Mr Bumble evolves from “in Oliver’s view an exceptionally vicious man” into a “henpecked husband” (Kincaid 64, 63). Mrs Corney is “much more vicious than Bumble” and has “a frightening competence which is born of deep cynicism; [she is] far more rigid than Bumble; [and is] frozen into the role of a monster” (66).

This relationship exposes the corruption of the Establishment via its ignorance, greed, rigidity and misuse of power. In so doing it is instrumental to the plot first in Mr Bumble’s suppression of Oliver himself and in Mrs Corney’s suppression of his identity, and then in their exposure of Monks’ plot against Oliver, and finally in the revelation and certification of Oliver’s identity. The very same merits which raised them to power are those which “reduced [them] to great indigence and misery, [to] finally [become] paupers in that very same workhouse in which they had once lorded it over others” (Ch 53). Happily I’m sure for both, they are separated by virtue of the Workhouse’s “wise and humane regulations . . . which . . . kindly undertook to divorce poor married people . . . and . . . took [a man’s] family away from him, and made him a bachelor” (Ch 2).

Mr Brownlow was to have married Miss Leeford, but, tragically, she died:

“It is because I was [Edwin Leeford’s] oldest friend,” Brownlow tells Monks. “It is because the hopes and wishes of young and happy years were. Bound up with him, and that fair creature of his blood and kindred who rejoined her God in youth, and left me here a solitary, lonely man; it is because he knelt with me beside his only sister’s death-bed when he was yet a boy, on the morning that would – but Heaven willed otherwise – have made her my young wife; it is because my seared heart clung to him from that time forth through all his trials and errors, til he died . . .” (Ch 49).

Mr Brownlow’s broken heart cleaved to his would-be brother-in-law, and now it cleaves to that man’s second son, Oliver. Mr Brownlow knows from Edwin the misery of the marriage which produced that “sole and most unnatural issue” – Monks. Further, he knows also of Edwin’s new love, though not by name, and that Edwin has plans to resolve his marriage and romantic entanglements. Thus, when Mr Brownlow suspects Oliver’s connection to his friend, via the portrait that was left with him by Edwin, he begins to search for Monks. He is unsuccessful until, by chance and/or coincidence, he is rediscovered by Oliver and enlisted by Rose. Armed with Nancy’s information, Mr Brownlow locates Monks and elicits his confession. (Ch 49)

Without Mr Brownlow, Rose would not have had such a staunch ally with whom to consult regarding Nancy’s information, Oliver’s identity would have remained a mystery to all but Monks and the Bumbles, and the threat of Monks & Fagin would always have loomed over Oliver’s well-being. Instead, Mr Brownlow is the means by which Oliver finally becomes a legitimate gentleman. And all because Mr Brownlow loved Miss Leeford.

As Nancy, Bill, and the recaptured Oliver pass Newgate Prison, Nancy’s latent womanly feelings are sparked by Oliver’s helplessness, by thoughts of the “fine young chaps” sitting on death row and the prospect of Bill sitting there one day. Her sympathy for the chaps sparks a reflexive response from Bill – “Mr. Sikes appeared to repress a rising tendency to jealousy” – and when Nancy expresses her feelings for Bill – “I wouldn’t hurry by, if it was you that was coming out to be hung, the next time eight o’clock struck, Bill. I’d walk round and round the place till I dropped, if the snow was on the ground, and I hadn’t a shawl to cover me.” – her remark is deflected with facetiousness and sarcasm – “‘And what good would that do?’ inquired the unsentimental Mr. Sikes. ‘Unless you could pitch over a file and twenty yards of good stout rope, you might as well be walking fifty mile off, or not walking at all, for all the good it would do me.’” Nevertheless, there is feeling on both sides of this relationship – Nancy’s is love, Bill’s is possessive and controlling jealousy.

From this point, Nancy struggles with the opposing forces of her compassion for Oliver against her love for Bill and loyalty to the Gang. Her compassion sends her to Rose with the sole intent of saving Oliver. During her second meeting with Rose, now accompanied by Mr Brownlow, Nancy agrees to deliver Monks. Bill, Fagin, and the Gang, however, are not to be touched; she has this promise from both Rose and Mr Brownlow.

Though encouraged and begged, by Rose at least, to save herself, Nancy’s love for Bill and loyalty to the Gang compel her to return “home”. It is love entangled with fear for even as “a vision of Sikes haunted her perpetually” she insists to Rose, “I wish to go back . . . I must go back . . . I can’t leave . . . I am drawn back to him through every suffering and ill usage, and should be, I believe, if I knew that I was to die by his hand at last”, and, “When such as me . . . set our rotten hearts on any man, and let him fill the place that parents, home, and friends filled once, or that has been a blank through all our wretched lives, who can hope to cure us? . . . pity us for having only one feeling of the woman left, and for having that turned by a heavy judgment from a comfort and a pride into a new means of violence and suffering.” (Ch 40) She returns “home” and is murdered.

Any feeling Bill has for Nancy can not supersede his anger at her treason against the Gang, and, more specifically, against his authority. Giving him laudanum is the real issue. That she would presume to thwart his authority, presume to control him – she, like Bullseye the dog, must be beaten into submission. Unfortunately, Bill’s temper and strength go too far and recoiling at the horror of his handiwork “he struck and struck again” (Ch 47 & 48). It is her return to Bill whom she loves beyond all reason (not unlike Pip for Estella in “Great Expectations”), which leads to her murder, which, in turn, exposes the Gang to capture and to justice.

The liaison between Agnes Fleming and Edwin Leeford produces the titular character whose (mis)fortunes we follow through his illegitimate birth in the Workhouse, his upbringing by hand, his stint at Sowerberry’s, his running away and being taken up by the London underworld, being rescued, recaptured and rescued again, until the final restoration to his rightful heritage and heir-a-tage.

This liaison is also the connective tissue between Mr Brownlow and the Maylie’s for, had Mr Brownlow married Miss Leeford, he would have Oliver’s uncle by marriage. Mr Brownlow feelings for Oliver alone would have motivated him to act to establish Oliver’s identity, but the added incentive of establishing the family connection between Oliver and Rose, and thus clearing “the blight” from Rose’s name, on behalf of his dear friend Edwin assured his active and eager participation.

But this illicit relationship would not have happened, and thus the novel would not have a subject, had it not been for . . .

The arranged marriage between the then 20 year old Edwin Leeford and an unnamed woman 10 years his senior is “wretched” and “ill-assorted” almost from the start. How their son, Edward, a.k.a. Monks’, was ever conceived is a wonder. Nevertheless, “the misery, the slow torture, the protracted anguish” of the marriage forced the couple to separate and become estrange. After Edwin’s death, young Edward/Monks is schooled by his vindictive mother to hunt down, if possible, his half-sibling and persecute him. This Monks’ nearly achieves with the help of the very underworld characters who have taken Oliver in, but this task is also the means by which Monks is exposed and castigated and the underworld characters brought to justice. (Ch 49 & 51)

Had this marriage not been wretched and the couple not separated, Edwin would not have fallen “among new friends” and met Agnes. Had he not met Agnes, Oliver wouldn’t have been born. And, well, you know the rest.

These relationships can seem contrived and coincidental, yet their importance and significance to the plot of “Oliver Twist” and also to Dickens’s canon and biography make them worthy of consideration. Their worth lies in giving us another tool with which “to assess the specific quality of Dickens’ imagination . . . to identify what persists . . . as a view of the world . . . and to trace the development of this vision . . . from one novel to another throughout the chronological span of his career” (Miller viii). One such quality, I contend, is the motif of amorous relationships, specifically failed relationships and/or unfulfilled love; it is a motif Dickens could not get away from either in his fiction or in his personal life.

As I mentioned above, the foundation for major plot lines in all of Dickens’s novels rests upon at least one failed amorous relationship. Dickens utilizes myriad permutations of character to illustrate and explore this motif – major and minor characters, the serious and comic, young and old, upper and lower class; they have ill-advised marriages, illicit love, unspoken love, unrequited love, lost love, obsessive love, and a few successful relationships. Some relationships are beautiful, some are just icky. In terms of Dickens’s biography, many of these troubled relationships are representative of his own experiences with with his wife, with his lover Ellen Ternan, and with other women, and on those of his parents, siblings, friends and acquaintances. In tracing the fictional relationships through the lens of the biographical relationships, it becomes evident that “Dickens is clearly working out his own troubled attitudes toward marriage, divorce, and adultery, and exploring the circumstances that may or may not permit the enlarging of one’s sexual experience” (Kucich 229), and, “In his novels sexuality remains unconscious but everywhere apparent; when directly expressed, it tends to be thwarted or blocked off” (Ackroyd 90). As his treatment of this motif progresses through his novels, Dickens’s writing and discussion becomes more compelling and so acts therapeutically for him if only as a means of venting his frustration.

Speaking of “Pickwick Papers” but applicable to the Dickens canon as a whole, Marcus explains: “What we are able to account for . . . is the manner in which Dickens took his personal experience and its problems and rendered them into an imaginative representation of life which is autonomous and yet at the same time inseparable from its source in his own life. . . . Dickens . . . rarely attempts a simple, direct transcription of his experience. . . for him the transformation of deeply personal emotions into images and ideas regularly took place beneath consciousness, at the initial states of conception. . . . [and] his novels take shape largely under the pressure of a progressive returning into consciousness of urgent and crucial events from his past. The principle of development in his work is the constant effort to deal more fully with these experiences by projecting them in novels, whose very shape and style communicate his changing sense of himself.” (Marcus 43-44)

Thus, I believe Dickens used his novels as an outlet through which to articulate and examine his conflicting and conflicted emotions, perceptions, beliefs, and strategies about love (agape) and desire (eros), two states whose coexistence is not guaranteed (love (agape) is a state of being, selfless, unconditional; desire/eros is a state of mind, need-based, egotistical) (wikipedia). For him, a resolution remained elusive – his “undisciplined heart” would always be the cause of his feeling an “old unhappy loss or want of something” (“David Copperfield” Ch 35, 44, 58). He died before he could work out the complication.

WORKS CITED:

Peter Ackroyd, “Dickens”

John Butt & Kathleen Tillotson, “Dickens at Work”

John Carey, “The Violent Effigy: A Study of Dickens’ Imagination”

Charles Dickens, “Oliver Twist” and “David Copperfield”

James R. Kincaid, “Dickens and the Rhetoric of Laughter”

John Kucich, “Repression in Victorian Fiction: Charlotte Brontë, George, Eliot, and Charles Dickens”

Steven Marcus, “Dickens From Pickwick to Dombey”

J. Hillis Miller, “Charles Dickens: The World of His Novels”

Sylvere Monod, “Dickens the Novelist”

Harry Stone, “The Love Patterns in Dickens’ Novels”, from “Dickens the Craftsman: Strategies or Presentation”, ed. Robert B. Partlow, Jr.

Chris, this is marvelous!!!! You’ve given us so much to consider and discuss! I’ll reread it (and more carefully/slowly) after work today, but wow! Agreed that Dickens seemed to be working out his own difficulties about relationships–and as you quote, the “old unhappy loss or want of something”–in each and every work.

There are so many things I’d love to discuss, including your description of the Corney/Bumble relationship as it “exposes the corruption of the Establishment via its ignorance, greed, rigidity and misuse of power.” And on the doubling of Noah/Charlotte vis á vis Sikes/Nancy.

Marvelous 🖤

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m likewise much impressed with this central insight about love relationships in Dickens, and that this theme is a recurring, almost obsessive one.

I’m eager to read your piece thoughtfully, carefully. For now, I just want to thank you for tackling this big motif in Dickens’ work.

It reminds me of the truism in the mental health field that therapists are REALLY working out their own “stuff”!!!

There seems to be a cathartic component here–Dickens discharging unresolved feelings and savoring good ones.

Anyway, more soon!

Daniel

P.S. Love this observation: Kudos to Harry for wanting to marry Rose regardless of her “acceptability”, for caring more for her as a person than for what Society thinks. AMEN.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Chris’ opening quote from Harry Stone really sums up one of the wonderful benefits of reading Dickens in chronological order as we are: “Encountered in a single work, such patterns are likely to seem topical or idiosyncratic. Encountered in book after book, however, they suggest a deeper significance: they suggest that they embody the author’s most profound hopes and fears.”

To see patterns, development, what comes round again and what drops off…

I too am fascinated by how the fear of failed romantic relationships is such a pattern with Dickens, even this early on, and as Chris mentions here, it’s quite literally from beginning to end, from Pickwick to Drood!

I think we can add to this the contrast of the repeated patterns of good/beautiful/disinterested friendship or sibling relationships. Mortimer and Eugene, the Pickwickians/Pickwick and Sam, Nicholas and Kate, the Brothers Cheeryble, the Punch siblings, Floy and Paul Dombey, etc. Even, as Chris mentions, it is the fidelity of Brownlow to his old friend that at least partially acts as impetus to all of the painstaking efforts he makes towards finding out Oliver’s true history. There are exceptions to the benevolent friend or sibling relationships, of course: the half-siblings Monks/Oliver; Stryver and Carton’s “friendship”—if it can even be called that—is certainly not a profound or healthy one, but more a vehicle for some witty humor and to give us another foil to Carton in his blustering companion; Louisa and Tom in Hard Times are another such relationship become unhealthy because the sacrifice and love are all on one side, or increasingly so. Even there, however, we have the sense in which the sibling relationship is such an intrinsically benevolent thing, gone awry due to Tom’s selfishness and his cold upbringing. In general, there is a pattern of benevolence here that contrasts with the patterns in romantic relationships, and makes both patterns more striking.

We see in the later novels some of the things immediately haunting Dickens coming up in his writing—that old dissatisfaction with his marriage, so sad and unfortunate. But this early on, especially just before or just after his marriage? Is there a sense that he intuited that he and Catherine were mismatched? I don’t know. I personally don’t know a lot about the relationship between his parents, John & Elizabeth. I feel like we “know” John (aka Mr. Micawber) a little more; and Elizabeth influenced Mrs. Nickleby and also Mrs. Micawber (whose semi-comical she-doth-protest-too-much-methinks assurances that she will never desert her husband make one wonder if there wasn’t some tension in reality, too), and I know that Dickens was always afterwards haunted that she had wanted young Charles, after his father’s release from the Marshalsea, to return to the blacking factory.

Dickens certainly uses these circumstances to work out his own difficulties, at least in imagination: Blackpool’s sad marital situation in Hard Times, Carton’s hopelessness vis-à-vis Lucie in A Tale of Two Cities; Clennam’s sense of having gotten too old for all youthful prospects, including a happy marriage; Jarndyce…etc. To work these things out through story, to exaggerate and reimagine, and even to form a kind of ideal out of giving certain things up (I won’t mention character names for fear of spoilers) is in some sense a kind of sublimation of our own hopes and fears, and **possibly** allows us to hope that he tried to act out these ideals in his later struggles with ET.

But, I’ll try not to fall down that rabbit hole…

Considering it from nothing more than a writer’s point of view, relationship drama certainly makes good drama/melodrama and pathos—and also good comedy. (Corney and Bumble are such an example of where it’s used to both comic and pathetic effect! And also thematically, as Chris says here: “This relationship exposes the corruption of the Establishment via its ignorance, greed, rigidity and misuse of power.” YES.) And yes to Chris’ comment here: “Dickens utilizes myriad permutations of character to illustrate and explore this motif – major and minor characters, the serious and comic, young and old, upper and lower class; they have ill-advised marriages, illicit love, unspoken love, unrequited love, lost love, obsessive love, and a few successful relationships. Some relationships are beautiful, some are just icky.” So, there’s probably a degree to which relationship drama is simply a **key ingredient** among others that Dickens has gathered from his experience as a writer—including from the stage—and certainly it’s a key ingredient in many a good story. They make good plot devices, as Chris says here regarding Oliver Twist: “each of the seven amorous relationships is influential, in varying degrees, to the development and/or resolution of the plot.”

LikeLiked by 2 people

Chris (et al.),

What a rich, layered, and thought-provoking exploration of this issue of the “undisciplined heart,” seeking and never fully finding a satisfying and lasting resolution to the matter of “true love.”

Rachel’s excellent insights into the ways of a writer, and the foils of various friendships in Dickens’ works, sheds light on another “face” of authentic human love: authentic friendship.

I’m reminded of C.S. Lewis’ “Four Loves.”

Three other thoughts emerge in my mind.

1. Benevolent providence: Chris, you wrote, “Had this marriage not been wretched and the couple not separated, Edwin would not have fallen ‘among new friends’ and met Agnes. Had he not met Agnes, Oliver wouldn’t have been born. And, well, you know the rest.”

This aspect of the Dickensian cosmology intrigues me greatly. It seems that Dickens was imbued with a sense of the Divine Hand in things–from the sweet way in which things work out for Sam to remain in service to Pickwick to the inadvertent hanging of Nancy’s “fair beau,” to this example of a wretched marriage yielding the beautiful fruit of good Oliver.

For me, this quality in Dickens brings me back to him again and again. Dickens’ genius is comprised of so many elements; this component–a view of things being ordered on a higher level–gives me a deep soul-satisfaction in reading him.

2. Principle of development: “The principle of development in his work is the constant effort to deal more fully with these experiences by projecting them in novels, whose very shape and style communicate his changing sense of himself.” (Marcus 43-44)

In a sense, all of Dickens’ work could be seen as an extended “Bildungsroman”–a coming of age, a maturing, a deepening of self-awareness and self-understanding.

I recently encountered the subtitle of a book about adult development, “From role to soul.” It seems that this trajectory is true of every human life that journeys towards true “individuation” (Carl Jung) and integration (Dan Siegel).

Interesting to think of how this human principle shows up in Dickens’ works.

3. “Undisciplined heart”: Chris, your concluding perspective seems to me to be truly apt and illuminating.

“For him, a resolution remained elusive – his ‘undisciplined heart’ would always be the cause of his feeling an old unhappy loss or want of something’ (“David Copperfield” Ch 35, 44, 58). He died before he could work out the complication.”

I think of current research on early and pervasive trauma and its lifelong effects, unless evidence-based treatment intervenes.

Dickens surely experienced pervasive trauma early on, and this likely led to a seeking, a questing, and an inability to find resolution.

Chris, your wonderful essay offers such food for thought!

Thank you for the time, effort, and erudition you bring to this dimension of the Inimitable.

Blessings,

Daniel

LikeLiked by 3 people

Extraordinary work, here, from all three of you. So much to consider, so much to apply to our “readings” of relationships, but not just regarding the “relationships,” in themselves, but the ways in which they become entangled with and “drive” the various aspects of their narratives (novels). I’m already applying so much of this material to my early reading of NICKLEBY, which in the opening 12 chapters is filled with “relationships”–some sort of positive but most mainly negative!

LikeLiked by 2 people