Wherein we are introduced to the fourth of Dickens’ serial novels, The Old Curiosity Shop (the fifth and sixth reads of our Dickens Chronological Reading Club 2022-24), and the accompanying periodical Master Humphrey’s Clock; with a glance at the context of Dickens’ life at the time–with other considerations. Finally, we have an overview of the whole of the reading schedule from July 19 through August 22; with a look ahead to the coming week.

by Boze

“A novel which reads like a cross between The Pilgrim’s Progress and Tales of the Genii, where the little heroine mixes with dwarves and giants, where the child-like are parodied by the childish, where there are dead children and waxworks, where the impulse towards Gothic historicity is continually displaced by the distorted figures of contemporary nightmare…”

— Peter Ackroyd, Dickens

Friends, this is a terribly exciting moment in our Dickens reading for two reasons. First, because today we embark on the delightful but oft-neglected Master Humphrey’s Clock, a weekly periodical that shows Dickens at his strangest and most relaxed. Second, because next week we begin The Old Curiosity Shop, one of my personal favorite Dickens novels, a dreamy picaresque featuring innocent girls, malevolent dwarves, kindly schoolmasters, traveling puppeteers, haunted waxworks, and what G. K. Chesterton called the one really great romance in all of Dickens.

For quick links, by topic:

- General Mems

- Dickens’s Life in 1840-41 and the Origins of The Old Curiosity Shop

- Thematic Considerations

- Additional References

- Reading Schedule

- A Look-ahead to Master Humphrey’s Clock

- Works Cited

General Mems

If you’re counting, today is day 197 (and week 29) in our #DickensClub! It will be Week One of Master Humphrey’s Clock and The Old Curiosity Shop, our fifth and sixth reads of the group. Please feel free to comment below this post for the first week’s chapters, or use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter.

No matter where you’re at in the reading process, a huge “thank you” for reading along with us. Heartfelt thanks to our dear Dickens Fellowship for retweeting these and for keeping us all in sync, and to The Circumlocution Office (on twitter also!) for providing such a marvelous online resource for us.

And for any more recent members or for those who might be interested in joining: the revised two-and-a-half year reading schedule can be found here. If you’ve been reading along with us but aren’t yet on the Member List, we would love to add you! Please feel free to message Rach here on the site, or on twitter.

Dickens’s Life in 1840-41 and the Origins of The Old Curiosity Shop

At twenty-eight years old, Charles Dickens was the most famous man in England. In the past four years he had written The Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist and now Nicholas Nickleby to great acclaim. His friend, the aging writer Thomas Carlyle, describes him during this period: “clear blue intelligent eyes, eyebrows that he arches amazingly, large protrusive rather loose mouth … a quiet shrewd-looking little fellow, who seems to guess pretty well what he is, and what others are.” A portrait of him undertaken in 1839 by Daniel Maclise echoes the sentiment, revealing a young man of remarkable confidence and self-assurance.

Yet he was also tired. As he neared the end of Nicholas Nickleby, Dickens wanted a great many things. He wanted out from under the thumb of Bentley’s Miscellany, having recently quarreled with Richard Bentley. He wanted a break, however brief, from the demands of writing novels. Fame was not guaranteed to last, and he wanted a steady means of income in the event that the public lost interest in his storytelling.

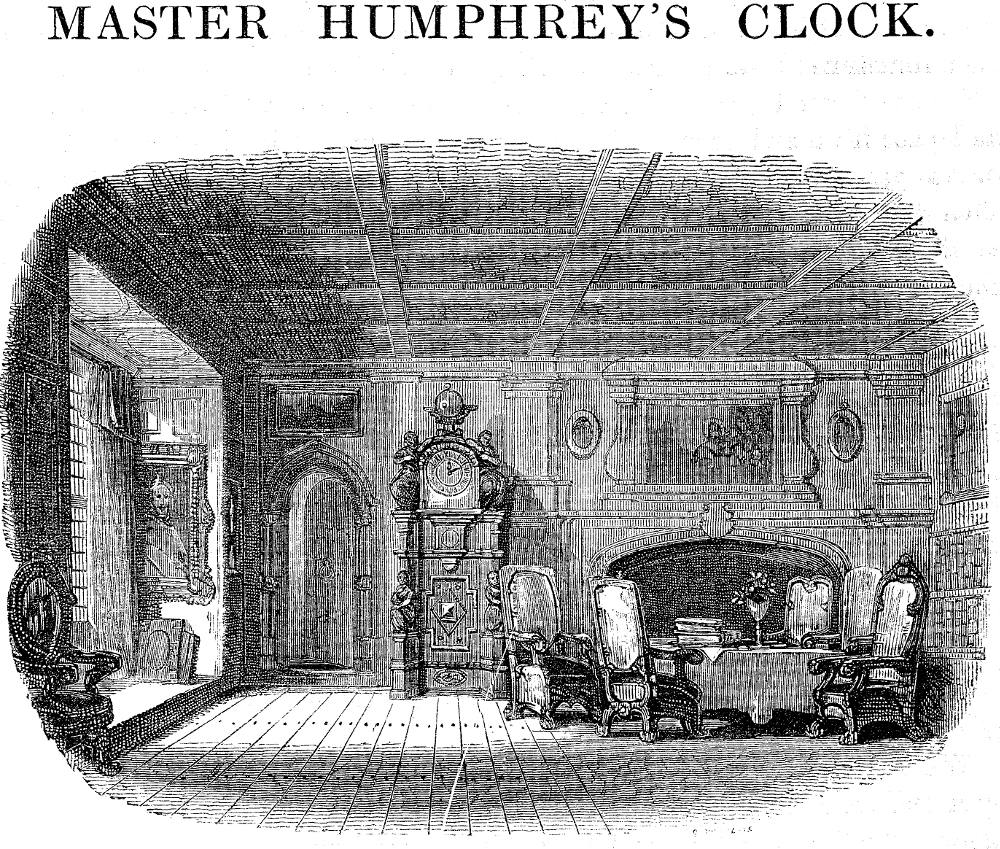

Thus the idea for Master Humphrey’s Clock was born. Dickens would start his own weekly periodical, a periodical of stories, weird sketches, funny musings, wherever his fancy led him at a given moment. He would write most of it himself, including the fan mail from fictitious personages, but would allow space for the contributions of fellow authors.

Once the idea seized hold of Dickens, it proved irresistible. He became so consumed with the planning that he neglected some of the planning for the later chapters of Nicholas Nickleby. If the periodical succeeded, he told a friend, it could bring him up to 10,000 pounds a year—a considerable sum in the 1840s. “The idea of a weekly periodical for which he would receive a regular income without having to extend his energies once more on a long novel clearly appealed to him,” notes Peter Ackroyd, “together with the fact that a periodical under his sole guidance and authority would confirm that link with his audience for which he was always searching and which might have been in danger if he had simply embarked upon another monthly series. He had a good idea of his audience and he knew that, to keep it, surprise and novelty were potent instruments.”

Alas, Master Humphrey’s Clock, while thoroughly charming in every way, did not fare as well as he had hoped. The British reading public proved surprisingly indifferent to a periodical largely written from the perspective of a wistful old man with mobility issues who pulls short stories out of a clock. Even the decision to revive Mr. Pickwick and the Wellers in later issues did not significantly increase sales, which had plateaued at around 50,000 a week. Again Dickens would need to do something novel and dramatic to recover the flagging attentions of his audience—and luckily, he had just the thing.

On a four-day trip to bath with John Forster to visit the poet Walter Savage Landor, Dickens encountered an abusive dwarf named Prior “who let donkeys on hire,” and who may have been the inspiration for Daniel Quilp. It was here, too, that he first conceived the idea of a short story about a lost, innocent girl wandering forlornly through the streets of London and rescued by Master Humphrey. As Michael Slater writes, “Once again, the image, hugely powerful and resonant for him, of a beautiful, vulnerable child wandering in the dark city seized his imagination as it had done in the case of Oliver.” Dickens had not intended this to be any more than a short story told by the old man—hence why the first three chapters of the novel are narrated by Master Humphrey, who then disappears from the book entirely—but the idea grew in his mind until it possessed him. Thus Dickens, who had set out in the new periodical to tell hundreds of stories, became gripped once more with the story of one solitary child. Chesterton felt there was something poetical in this: “The truth is not so much that eternity is full of souls as that one soul can fill eternity.”

A Note on the Illustrations:

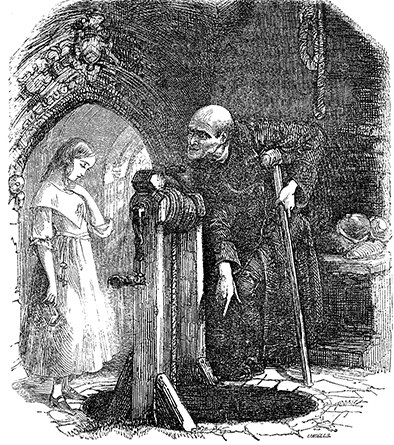

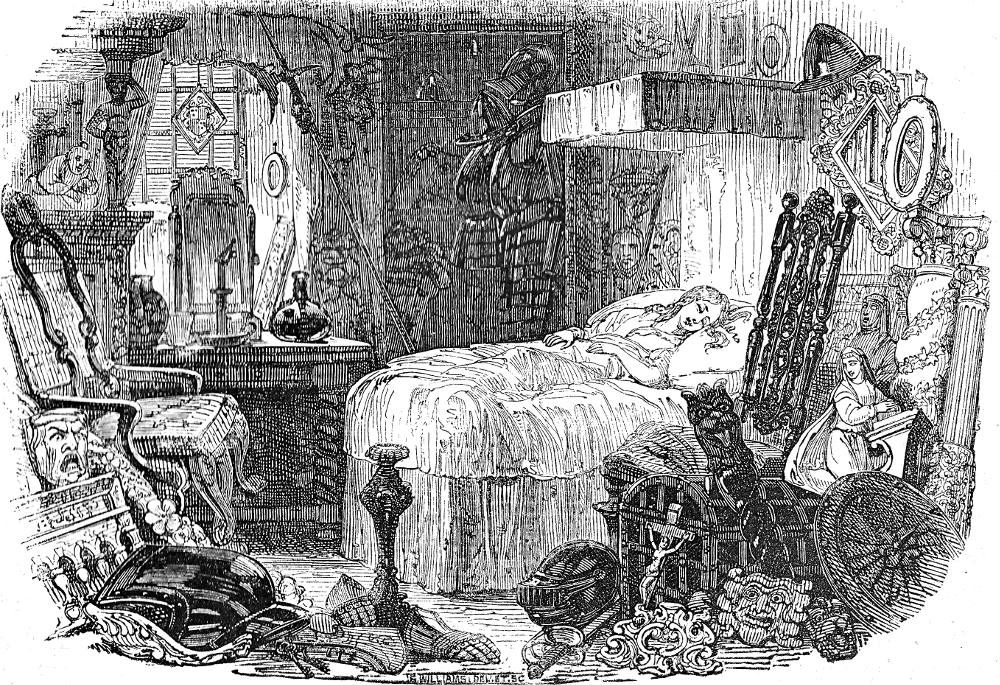

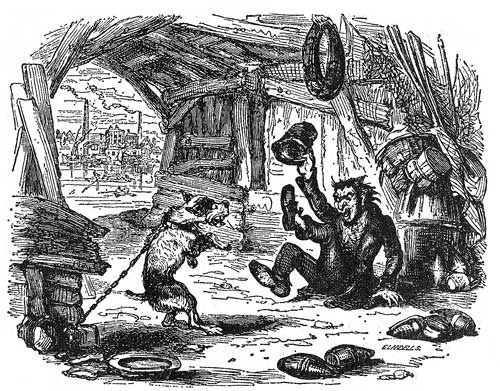

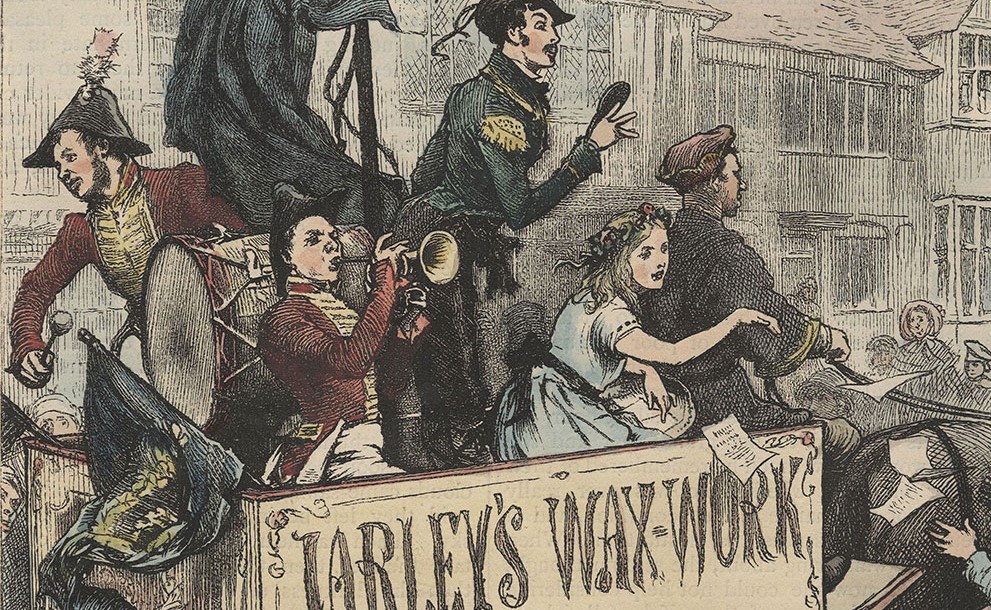

The magical writer-illustrator collaboration between Dickens and “Phiz” (Hablot K. Browne) continues with Master Humphrey’s Clock and The Old Curiosity Shop. However, illustrations on the latter become something of a team effort with the inclusion of fourteen woodcuts by George Cattermole—adding an additional Gothic flair particularly to the sequences near the kindly schoolmaster’s old church—and one contribution apiece from Daniel Maclise and Samuel Williams. Phiz, however, remained the primary illustrator at sixty-one woodcuts, particularly for action or character-caricature visuals; Cattermole’s talents were utilized for the architectural and sentimental, according to Victorian Web.

Dickens, of course, had his say as the presiding spirit.

The steel-engraving method which we’ve become accustomed to from Phiz certainly had a greater capacity to show detail; woodcuts, on the other hand, could be inserted right alongside the text.

“Wood engraving was a mechanical process in which the drawing was transferred to a wood block using transfer paper. The engraver would then cut away the wood in areas where there were no lines, leaving the drawing in high relief. Since the lines to be printed were raised, like the type, the illustration could be inserted into the page along with the text. Wood engraving was usually done by a craftsman other than the original illustrator…”

https://www.charlesdickenspage.com/charles-dickens-illustrations.html#illustration-methods

In Dickens and Phiz, Michael Steig argues that the illustrations in The Old Curiosity Shop, as in Barnaby Rudge, “are more truly integral parts of the text than any of the other illustrations of Dickens’ novels” (Steig 51). This is in large part due to the weekly rather than monthly installments; there are simply more illustrations for an equivalent amount of text—by two or three times (Steig 52).

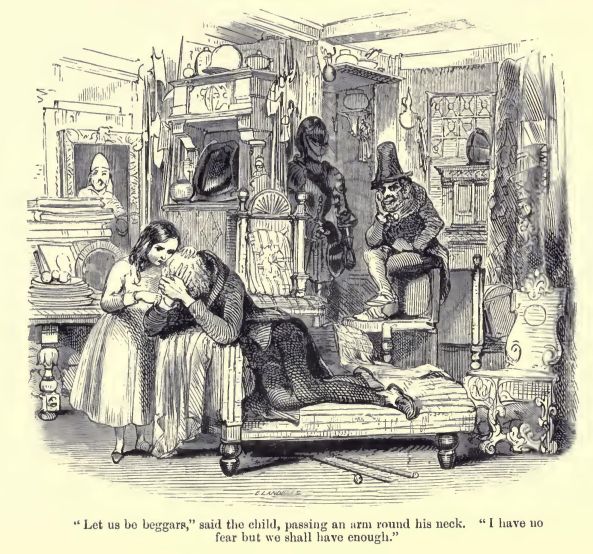

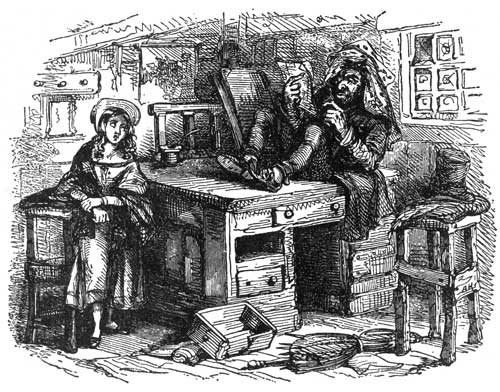

Below, you can see samples of the four different illustrators:

Left to right: Phiz; Cattermole; Maclise; Williams

Thematic Considerations

The World as Fairy-Tale

“More and more, he must, consciously or unconsciously, have come to realise that the grand unifying theme of the story was the creative imagination itself, the telling of stories. The man in chapter 44 who tends the furnace reads stories in his fire … the Bachelor in chapter 54 loves to indulge in ‘teeming fancies’ with regard to the antiquities in his village church, and Dick Swiveller’s improvisation of fantastic legends and magical transformations of reality is central to the tender comedy of his relationship with the little Marchioness.”

— Michael Slater, Charles Dickens

Dickens had a lifelong fascination with fairy-tales, dating back to his reading of the Arabian Nights as a child and the macabre stories that his Cockney nurse, Mary Weller, used to tell him. Those influences came to the fore in the writing of The Old Curiosity Shop, which John Forster wrote had less conscious conception than any of Dickens’s other books. He was writing largely by instinct, and what emerged was something strange, primal, archetypal, drawing on the deep wells of his childhood reading and stories. “The controlling motifs that welled up so spontaneously,” writes Harry Stone, “had the attributes (and often the lineage) of fairy tales, fables, and allegories,” foremost among them the age-old fairy-tale motif of the innocent child wandering through a surreal landscape of giants, monsters and grotesques.

The Nightmare World of Childhood

“Quilp indeed was a perpetual nightmare to the child, who was constantly haunted by a vision of his ugly face and stunted figure. She slept, for their better security, in the room where the wax-work figures were, and she never retired to this place at night but she tortured herself—she could not help it—with imagining a resemblance, in some one or other of their death-like faces, to the dwarf, and this fancy would sometimes so gain upon her that she would almost believe he had removed the figure and stood within the clothes.”

— The Old Curiosity Shop, Chapter 29

Harry Stone has argued that the flip side of Dickens’s fascination with fairy-tales is that at times his stories take on the quality of nightmare. Wonder and terror are his animating impulses, and never was that clearer than in The Old Curiosity Shop with its freaks and furnaces and glass-eyed grotesques. One might almost see the book as a Victorian precursor to the 1955 film The Night of the Hunter, also a story of children being pursued across an increasingly surreal, Gothic landscape by a demonic figure. There are hints, too, of the Wonderland books that Lewis Carroll would later write.

Good and Evil Binaries and the Allegorical Mode

Much criticism of the novel has centered on its alleged lack of realism, on the one-dimensionality of the central characters who represent opposing binaries of good and evil. Paul B. Davis argues that Dickens wrote the book in the allegorical vein of Pilgrim’s Progress, as Dickens himself only belatedly realized near the story’s completion—hence the passage, which he added to the opening chapter, in which Master Humphrey says Nell “seemed to exist in a kind of allegory.” In Davis’s estimation, Dick Swiveller—by rejecting the binaries embodied by the other characters—redeems the novel from itself. He “synthesizes the polarities of Nell and Quilp to the possibilities of compromise … [his] ability to adapt to changing circumstances enables him to survive and grow,” whereas Nell and Quilp, by refusing to evolve, ensure their own destruction. Harry Stone avers, calling the novel a series of schematic set pieces and abstractions existing more in the realm of the fairy-tale than the psychological novel.

Additional References

Katie Lumsden at Books N’ Things offers her thoughts on the good and the bad of The Old Curiosity Shop and its troubling portrayal of dwarves. Anton Lesser, arguably the world’s greatest reader of audio books, has recorded the unabridged book on audio. There are also several television adaptations, among them a 1979 BBC miniseries starring Trevor Peacock and Sebastian Shaw and a 2007 ITV miniseries starring Derek Jacobi and Toby Jones.

Reading Schedule

| Week/Dates | Chapters | Notes |

| Week One: (OPTIONAL) 19-25 July | Master Humphrey’s Clock | The full introductory frame for The Old Curiosity Shop, for those interested. |

| Week Two: 26 July – 1 Aug | 1-18 | Here we begin The Old Curiosity Shop. Since these were published in weekly rather than monthly installments, we’ve divided the book up into (approximate) quarters, rather than by installment sections. |

| Week Three: 2-8 Aug | 19-37 | |

| Week Four: 9-15 Aug | 38-55 | |

| Week Five: 16-22 Aug | 56-73 |

A Look-ahead to Master Humphrey’s Clock

This week we’ll be reading Master Humphrey’s Clock. You can choose to read along or skip ahead to the opening chapters of The Old Curiosity Shop. There are a number of places (including Gutenberg) where they can be downloaded for free.

Works Cited

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens. New York: HarperCollins, 1990.

Chesterton, Gilbert Keith. Appreciations and Criticisms of the Works of Charles Dickens. London: J. M. Dent & Sons, 1911.

Davis, Paul Benjamin. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. Checkmark Books, 1999.

Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens: A Life Defined by Writing. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington and London: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Stone, Harry. Dickens and the Invisible World: Fairy Tales, Fantasy, and Novel-Making. Indiana University Press, 1979.

Stone, Harry. The Night Side of Dickens: Cannibalism, Passion, Necessity. Ohio State University Press, 1994.

Tomalin, Claire. Charles Dickens: A Life. New York: Penguin, 2011.

I know that this isn’t exactly part of Master Humphrey, though it may be included in some editions, but I would like to encourage everyone to read the short story “The Public Life of Mr Tulrumble” (available here: https://vsfp.byu.edu/index.php/title/public-life-of-mr-tulrumble/). It’s Dickens at his funniest and most charming, but with a bit of the enchanting descriptive flair that we see in A Christmas Carol or some of the short stories in Pickwick Papers. The titular Mr Tulrumble finds himself mayor of Mudfog when the old mayor, Sniggs, unexpectedly dies at the youthful age of eighty-five. Suddenly risen from his once lowly station, Mr Tulrumble decides to give the people of Mudfog a procession such as they’ll never forget, the highlight of which is a layabout named Bottle-Nosed Ned wearing an enormous suit of armor. But alas, things go horribly, hilariously wrong, as they often do. Ned and Mr Tulrumble are instantly memorable – Ned with his jovial face and suit too big for him, Mr Tulrumble with his total confidence that the good people of Mudfog will parade the streets to see this extraordinary sight (“A live man in brass armour! Why, they would go wild with wonder!”). And the descriptions of the mud and sun and fog are some of Dickens’s best – the sun rises very blood-shot around the eyes, “as if he had been at a drinking party overnight, and was doing his day’s work with the worst possible grace,” while “A cracked trumpet from the front-garden of Mudfog Hall produced a feeble flourish, as if some asthmatic person had coughed into it accidentally.”

LikeLiked by 2 people

I just now saw this marvelous comment!!! 😀 We are both spreading the good news about Mudfoggian joys ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

Boze, thanks much for your work on giving us perspective on the new reads. I’m definitely intrigued by both: “Master Humphrey’s Clock” and “The Old Curiosity Shop.”

And, thanks too for the tantalizing tidbits from ““The Public Life of Mr Tulrumble”! Descriptive and immensely funny for sure!

Among the many insights, these especially captured my attention.

1. “Dickens at his strangest and most relaxed”: I’m curious now about “most relaxed.” I’m guessing that there is a limpid quality to his writing–flowing, unforced.

2. Dickens’ perceptions: “ . . . who seems to guess pretty well what he is, and what others are.” (Carlyle) Excellent!

3. “his Cockney nurse, Mary Weller”: I didn’t remember where “Weller” might have come from. Cool!

4. “Anton Lesser, arguably the world’s greatest reader of audio books”: Now, I’m wondering if there is consensus on this claim! I, for one, would sign the petition to name him such!

Thanks again, and I look forward to this next stretch of the journey.

Daniel

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s interesting that Master Humphrey’s Clock started with a positive portrayal of a deformed character and ended up (sort of) being a negative portrayal of a little person (Daniel Quilp in The Old Curiosity Shop.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Boze: a great introduction to what sounds like a very complex novel. PILGRIMS PROGRESS hints of more time on the road with our protagonist, the sense of good, evil and temptation–either satisfied or denied–and the meeting of many interesting characters who stand for various vices and virtues. Again, as you postulate, we’re dealing with the subjugation and possible freedom of children who are at the mercy of the surrounding “adults,” as well as the condition of women, young and old, in 1840’s England. This is gonna be quite a journey! And all these possibilities sound pretty darn familiar….

LikeLiked by 2 people

In “Master Humphrey’s Clock” Dickens once again experiments, but this time with no great success. I found Humphrey and his friends to be dull and their stories uninteresting and plodding. Even the reintroduction of Mr Pickwick, Sam and Tony Weller, do very little to liven the text. It’s as if Dickens is TELLING rather than SHOWING. Too much musing by Master Humphrey on the same topics (being alone, being ok with being alone, the Clock, death, memories of the dead, beauty, his relationship with his three friends and his neighbors). Humphrey says, “We are men of secluded habits, with something of a cloud upon our early fortunes . . .” – Would that this had become the foundation of MHC, there seems there is a lot to mine here that Dickens does not take advantage of – more untold stories.

Sylvere Monod sums up the problem of MHC thus: “Whoever has examined . . . the few technical weaknesses and uncertainties as well as the exceptional appeal of [Dickens’s] first works of fiction must see that a project [like ‘Master Humphrey’] could only impair Dickens’ originality by causing him to interrupt his progress in the new genre he was beginning to master, and look for success along lines that many another writer might have followed with greater ease than he” (168). In other words, Dickens was just beginning to get his novelistic legs under him after “Nickleby” when suddenly he shifts gears and reverts to an 18th century periodical model of satire, tales, commentary, etc. revolving around an individual or club (Chittick 139-143; Macus 131).

Perhaps had Dickens taken a little more time between projects he would have been better able to contemplate his position. Again Monod sums up the situation nicely: “‘Nickleby’s’ unquestionable success might have induced the author to believe he had found the right way, and that after the fresco-like meanderings of ‘Pickwick’ and the sensational structure of ‘Oliver Twist’, he need only in the future refrain from going to either of these extremes, as he had already done in his third fiction, by granting prominence, within a carefully constructed though unobtrusive frame, to those elements which had made the irresistible appeal of all three of his previous books, namely, the creation of lively characters presented in a succession of varied and diverting scenes.” (166-167)

Dickens does eventually land upon this mode of operation, and thus our Reading Club exists!

I’ve been traveling with family during our break – nice timing, purely coincidental but no time to watch RSC’s “Nickleby” (for some odd reason I couldn’t talk the family into watching it while at the seashore). I very much enjoyed the commentary though and have begun to watch it on my own. I’m looking forward to getting back into the swing of things with “The Old Curiosity Shop”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oops – Works Cited:

Sylvere Monod, “Dickens the Novelist”

Kathryn Chittick, “Dickens and the 1830’s”

Steven Marcus, “Dickens from Pickwick to Dombey”

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hadn’t read Master Humphrey’s Clock before, though I’d heard the story behind it and the genesis of The Old Curiosity Shop, and I have to say I was a little disappointed by it too.

LikeLike

I am pretty sure I’m in the minority, but I have a huge soft spot for Master Humphrey’s Clock. I suppose this gentleman managed to inspire in me those “feelings of homely affection and regard” that he’d hoped to. I also just find it utterly charming that Dickens, as Boze has it here in his intro, somehow thought this whole endeavor was a good idea: a lonely, solitary, slightly disabled gentleman who is haunted by the past, and keeps stories in his clock case to pull out and share with his readers from his cozy chimney-corner.

Dickens loved the weekly periodical idea. In Simon Callow’s “Dickens and the Great Theatre of the World,” Callow writes that Dickens was “inspired by the great eighteenth-century magazines, Tatler and The Spectator”—both of which formed a part of his childhood reading. Nonetheless, it would seem that Master Humphrey was not the right or popular vehicle for it, and Dickens made the decision to let go of it after his Highland tour.

Whatever Dickens was thinking with this, it is, in some degree, perhaps an exercise in a grief therapy of sorts; perhaps it is that he began this while still somewhat fresh from the sorrow of losing Mary Hogarth (but I wonder if it ever ceased to be a “fresh” source of recollection for him), and that something of that nature lies behind Master Humphrey’s own reclusive situation. And if Dickens felt this ache, this nostalgia for a secret sorrow or past loss, he figured that others, too, might be able to find sympathy and comfort in it? Certainly, memory is everywhere: his “old cheerful companionable Clock” that “is associated with my earliest recollections”—“feeling such society in its cricket-voice”—and “when my thoughts have wandered back to a melancholy past…its regular whisperings recalled them to the calm and peaceful present.”

“But memory was given us for better purposes than this: and mine is not a torment, but a source of pleasure. To muse upon the gaiety and youth I have known, suggests to me glad scenes of harmless mirth that may be passing now. From contemplating them apart, I soon become an actor in these little dramas; and humouring my fancy, lose myself among the beings it invokes.”

As Chris writes: “Humphrey says, ‘We are men of secluded habits, with something of a cloud upon our early fortunes . . .’ – Would that this had become the foundation of MHC, there seems there is a lot to mine here that Dickens does not take advantage of – more untold stories.” I agree with this, and I can’t help but wonder whether Dickens had intended to do this all along; had it really lasted and had the public imagination taken hold about Master Humphrey, I can’t help but think that the new society of Mr Pickwick would have helped draw out some of these untold stories—somewhat in the way that he relates that he himself is the unnamed gentleman in The Old Curiosity Shop—and perhaps he (Master H) would have a more magnificent send off and finale when the weekly periodical wrapped up. As it is, his end is as quiet as his reclusive existence; and it works—only, that I think Dickens might have done a little something different and more unexpected, had there been enough readership interest in the gentleman to see it through. (I can’t help but think that he’d intended that Pickwick & the Wellers should be more regular characters too. They make great cameo appearances, but surely if one has a new member such as Mr Pickwick, Dickens intended to use him fully…?)

A few other little notes of things I noted or loved:

~ The shady corner he lives in—I wonder if it is Soho? He describes it very much the way the Manettes’ home will be described later, in A Tale, with its silence and shade and “a paved court-yard so full of echoes.”

~ I think we’d have heard more of the romantic spirit of Master Humphrey and his fireside friends, had it gone on longer: these men “whose enthusiasm nevertheless [despite past sorrows] has not cooled with age, whose spirit of romance is not yet quenched, who are content to ramble through the world in a pleasant dream, rather than ever waken again to its harsh realities. We are alchemists who would extract the essence of perpetual youth from dust and ashes, tempt coy Truth in many light and airy forms from the bottom of her well, and discover one crumb of comfort or one grain of good in the commonest and least regarded matter that passes through our crucible.” Is this a kind of Romance of the ordinary? (Later, at the entrance of Pickwick, there is an allusion to Don Quixote, and I think this is appropriate.)

~ “His face was like the full moon in a fog…”

~ Great sympathy with Jack Redburn, “having had all his life a wonderful aptitude for learning everything that was of no use to him.” 😊 And his tendency to move the furniture about—sounds like Dickens himself!

~ LOVED the letter from “Belinda” and all her “self snatchation” and her “blandishing enchanter” who would “still weave his spells around me”—this whimsical, strange madness was **very** reminiscent of the peculiar humor and strangeness of Susanna Clarke; I again can’t help but notice (as Boze and Dana have also noted) how very much she was influenced by early Dickens.

~ SAM WELLER. (What more can I say…?) “Well, I’m agreeable to do it…but not if you go cuttin’ away like that, as the bull turned round and mildly observed to the drover ven they wos a goadin’ him into the butcher’s door.”

~ Tony Weller, the other half of “the bodyguard,” brilliant as ever. “Samivel Veller, sir…has conferred upon me the ancient title o’ grandfather vich had long laid dormouse…” ;D

~Dear Mr Pickwick. Ever like the sun. (I actually put little “sun” marks on parts in my copy that were especially Pickwickian, including when he “was taken with a fit of smiling, full five minutes long.”)

~ I loved the whole passage about St Paul’s Cathedral and its clock. “…the fancy came upon me that this was London’s Heart, and that when it should cease to beat, the City would be no more.”

LikeLiked by 1 person