Wherein we revisit our third week’s reading of Barnaby Rudge (Week 38 of the Dickens Chronological Reading Club); with a summary and discussion wrap-up; and a look-ahead to Week Four.

By the #DickensClub members, edited/compiled by Rach

Ghosts, murderers, riots, villainous MPs, imprisonment, burning old Gothic piles, devils and Protestant kettles…we’ve really had it all during our third week’s journey with Barnaby Rudge!

And friends, what a joy to have had our first online chat, for those who could make it. A heartfelt “thank you” for joining! It was wonderful to be able to put faces and voices to names, and our only trouble was that there was not enough time to talk about everything we might have!

Here are some quick links for our chapter and discussion summaries this week:

General Mems

It was such a delight to chat with my co-host Boze and our wonderful member Deacon Matthew, on his podcast–a beautiful podcast on faith, seminary life, and literature–discussing Oliver Twist! My earlier discussion with Deacon Matthew on The Pickwick Papers (especially touching on the theme of “Dickensian contrasts”) went up a week ago. Our discussion of Pickwick begins at about 14:00.

This week, due to having Covid while preparing for my sister’s wedding, I’ll postpone our final wrap-up (which would usually be posted on 3 October) until 10 October. Another week to get in any final comments on Barnaby Rudge!

And what a delight to have had our first Dickens Club online chat this week! Huge, huge “thank you” to everyone who attended. Please see below for more details–I’d absolutely love to hear from you if you’d like to join in future!

If you’re counting, today is day 266 (and week 39) in our #DickensClub! It will be Week Four–the final week–of Barnaby Rudge, our seventh read of the group. Please feel free to comment below this post for the fourth week’s chapters, or use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter.

No matter where you’re at in the reading process, a huge “thank you” for reading along with us. Heartfelt thanks to our dear Dickens Fellowship, The Dickens Society, and the Charles Dickens Letters Project for retweets, and to all those liking, sharing, and encouraging our Club, including Gina Dalfonzo, Dr. Christian Lehmann and Dr. Pete Orford. Huge “thank you” also to The Circumlocution Office (on twitter also!) for providing such a marvelous online resource for us.

And for any more recent members or for those who might be interested in joining: the revised two-and-a-half year reading schedule can be found here. Boze’s introduction to Barnaby Rudge can be found here. If you’ve been reading along with us but aren’t yet on the Member List, we would love to add you! Please feel free to message Rach here on the site, or on twitter.

Barnaby Rudge, Week Three (Chapters 40-59): A Summary

Sir John Chester is now not only a “knight,” but a Member of Parliament. Hugh comes in late one night to Chester’s lodgings, bringing him a paper found at the Maypole, which Chester recommends he destroy for both their sakes.

Gabriel Vardon, as a Royal East London Volunteer, is getting ready to participate in a parade. Dolly arrives, wondering about a mysterious ghost story, and where Emma’s uncle has gone to.

We find out that both Miggs and Mrs. Varden are involved with Gordon’s movement. Upon Varden’s return from the parade, Haredale meets up with him, discussing his attempts to find the Rudges, and how he intends to stay secretly at their old deserted home for the time being, to keep an eye on things. (Here he stays awake by night, watching and listening, while resting during the day.)

Haredale encounters two old schoolfellows while in London, where signs of No-Popery unrest are starting to occur. Haredale voices his disdain of Gordon’s movement; as he leaves, Haredale is hit in the head by one of several stones thrown at him—this one, we find out, was thrown by Hugh. John Grueby comes to his aid and sees him off in a boat. Meanwhile, Gashford encourages Hugh and Dennis in their attacks on Haredale and his property.

The Rudges have found some relief in country life and a simple living. However, it is not long before a blind man—Stagg—talks to Mrs. Rudge. He had (at the request of one whose name causes terror in Mrs. Rudge) been searching for them. Stagg threatens to disclose their location unless she’ll pay him twenty pounds—and that she knows where she can request it (i.e. at the Haredale’s, whose annuity she had given up). She gives him her whole savings, but says she needs time to get the rest. Stagg discusses with Barnaby means whereby the latter can get rich, and that it has to do with leaving home and being surrounded by crowds of people—by this means, he can make life easier on his mother and provide for her. Barnaby is excited by the prospect.

With almost no money left, Mrs. Rudge decides to take Barnaby back to London where they have a better chance of “hiding” amid the crowds. People start paying to see Grip. Barnaby is still thinking on his discussion with Staggs. Their arrival in London, however, coincides with another fateful day: 2 June 1780, the beginning of the Riots. Barnaby sees in the crowd an echo of the prospect for getting rich that Stagg talked about. With the encouragement from several rioters, including Lord Gordon who appears to take a fancy to the idea of Barnaby being among the association, Barnaby ends up being taken under Hugh’s wing, who sees Barnaby as an asset to their movement and willing to do anything, with direction. Barnaby and Mrs. Rudge are separated in the chaos as the crowd marches towards Parliament, with Barnaby and Hugh at their head—Barnaby holding up their banner.

Some violence breaks out as the crowd hears that Parliament is delaying considering their petition.

Gashford meets up with Hugh and Barnaby later at an inn, where he provokes Hugh to greater acts of violence, and the looting of Catholic churches ensues.

Sim breaks with his old master, Gabriel Varden, who does everything he can to keep Sim—drunk, reckless—from going back out to the crowds and getting himself killed or captured. Sim escapes, and outruns Varden.

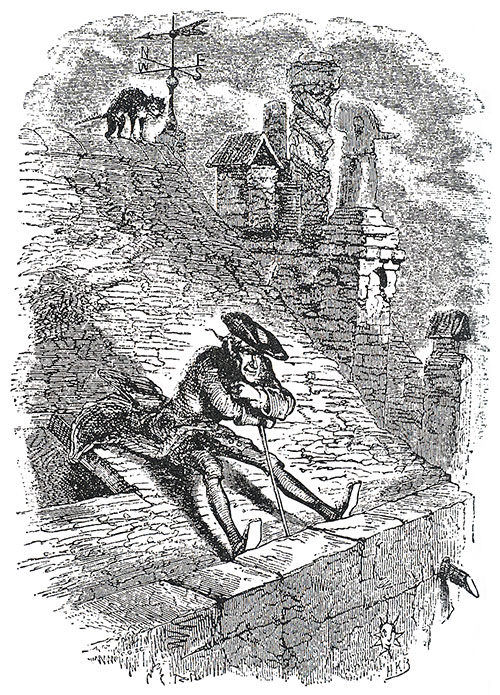

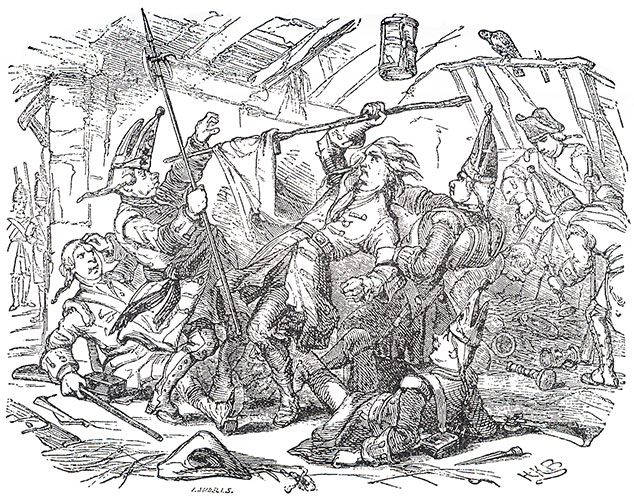

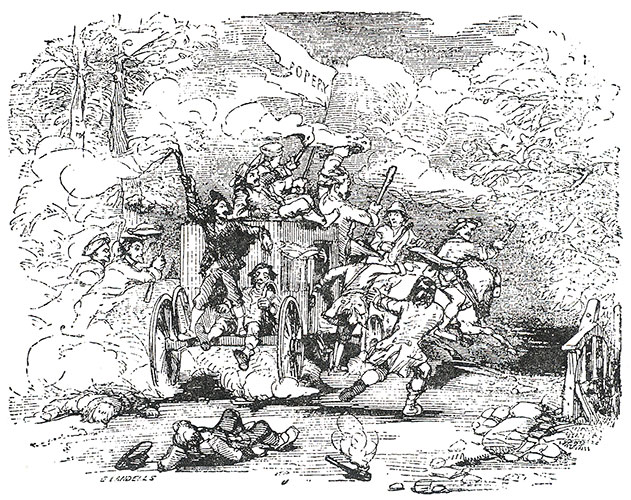

Destruction and looting increase, and finally Hugh leads a crowd of No-Popery men to burn the Warren—after looting the Maypole for alcohol and tying up John Willet.

The Warren is burned, and Dolly and Emma are carried off by the crowd. When Haredale and Solomon Daisy arrive at the Warren—after releasing John Willet and plying him for information—all that is left is the alarm bell. But there is a mysterious figure there—a ghost, Daisy thinks.

Haredale arrests Barnaby Rudge (Senior), charging him with the double murder (of Reuben Haredale and the servant) so long ago.

Meanwhile, the younger Barnaby, still standing guard, is discovered and arrested by soldiers who discover him along with the loot—which Grip had pointed to—and is taken to Newgate.

Hugh takes Dolly and Emma to a cottage—not before a dismal carriage ride where he puts his arms around them, threatening them with kisses each time they scream—where Sim arrives. Dolly repentantly considers her treatment of Joe.

Discussion Wrap-Up

What We Loved–and Didn’t

The Stationmaster commented on a few surprising twists this week, related to Sim, and John Willet:

Barnaby Rudge: The 1960 Adaptation

Chris kindly shared with us her thoughts on the 1960 adaptation of Barnaby Rudge, which sounds like it has many things worth experiencing, the big disappointment being the lack of a gripping Grip:

Dickens’ “Writing Lab”: Characterization

The Stationmaster beautifully continues the discussion on characterization from last week, discussing interesting surprises (Haredale’s standing up to Gordon; Grueby’s unexpected aid of Haredale), and a discussion about whether Barnaby himself might be considered an “antihero”:

Lenny responds:

The Stationmaster continues the characterization discussion, but with a few questions–e.g. why Hugh is so attached to Barnaby, who, the Stationmaster feels, “doesn’t really seem that competent”:

Chris responds about the Hugh-and-Barnaby relationship in this insightful response; there really are a number of parallels between the two, and their history together helps shed light on Hugh’s sense of reliance on him:

Motives…

Religion, politics, or self-serving motives? Chris discusses the “secular and anarchic intrigue that results in arson, sacking, and kidnapping”–and how some of our characters “relish the opportunity to act and exceed the expectation of those whom they serve”:

Gordon, Barnaby, and Grip

Lenny brings up the question about character names, and whether this was a “symbolic” move on Dickens’ part.

Here he also continues the conversation on why there is no “central character” in Barnaby Rudge, and why Dickens names the book as he does.

I respond both to the Stationmaster and to Lenny, my thoughts on the symbolism of Barnaby as the embodiment of these problematic riots, the influence of the mob and noisy rhetoric on well-intentioned people, and also Grip’s role as the “devil” on the shoulder, instigating to violence:

The Stationmaster continues along the same lines of thought, considering Chris’ earlier reflection on how Barnaby and Gordon are given a number of parallel traits:

And more on Grip, the mysterious raven:

The Dickens Club’s First Online Chat

We had such a lovely turnout for our first online chat! I confess that I got so absorbed in hearing everyone’s story about “how Dickens happened to you,” and on Barnaby Rudge after, that I didn’t take detailed notes.

We had in attendance: Boze, myself (Rach), Dana and Daniel, Lenny H., Chris M., Deacon Matthew K., Laura S., Henry O., the Stationmaster, and Steve R.! Already, we had a great deal to talk about on Barnaby Rudge. Among other things, we discussed: the comparisons between Gordon and Barnaby; the fantastic villain Sir John Chester; the novel’s title and why we have no “central” character; the women in Dickens (Miggs, Dolly, Emma, Mrs. Varden, Mrs. Rudge).

I sure hope you can all make our next meeting on Sat, 5 November, 11am PT/2pm ET/6pm GMT! Because we’ll be at the tail end of our optional reading of American Notes (an essay collection from Dickens’ American tour, and a great segue into Martin Chuzzlewit, which we’ll jump right into that following week) we’ll probably be focusing a good deal on the Notes, and any final thoughts on Barnaby Rudge. I will try and read ahead on the Notes during our next break, to have some recommendations for essay highlights for those who want to dip into the American Notes but who don’t have time to read it in full.

If you are more familiar with this work and have an essay–or several–that are especially worth dipping into, please share!

If I haven’t contacted you to send a link to our online meeting, it’s because I’m not sure who all is currently reading or interested, and/or I don’t have everyone’s email address. If you’d like to join, please feel free to message Rach on twitter, or to email her!

A Look-Ahead to Week Four of Barnaby Rudge (27 Sept – 3 October, 2022)

This week we’ll be reading the final quarter of Barnaby Rudge (Chapters 60-“82”, or “Chapter the Last” as the final one is named).

The final wrap-up will be posted during our “break,” on 10 October. (This will be an extended break between novels, unless you’re going to be reading Dickens’ travelogue about America with us…American Notes!

If you’d like to read it online, here’s a link to our trusty Circumlocution Office, with additional resources. It can also be downloaded at Gutenberg.

Hi friends! Sos sorry…I thought I had this scheduled to publish automatically at 4:30am PT, but clearly it didn’t, so I had to go back and manually publish it late.

For those who didn’t see the little twitter notification, I just got hit with Covid the night before last–not a good time, because my sister’s wedding is this weekend! 😢– so I will plan on postponing our final wrap-up until October 10, which will give us an extra week to discuss any final thoughts on Barnaby 🖤.

Sorry if I’ve missed anything here…my brain has been a bit out to lunch! Please let me know, so I can edit it.

I’m really curious: who all is going to be reading Dickens’ American travelogue, AMERICAN NOTES? If you don’t, we’ll have an extra long break between novels, but I’m so curious, as it is one I haven’t read before, except for snippets. Boze and I were talking about how it should pair so nicely with reading his “American” novel, Martin Chuzzlewit! 🖤

LikeLike

So sorry to hear you got hit by the evil crud. 😦 Praying for a quick recovery.

And I’m also so sorry, again, to have missed the online meeting. I will be there next time if I have to tattoo a reminder of the date on my arm!

As for American Notes, I may jump in for that one if I can manage it, as I started reading it some time ago and would really like to get back to it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh THANK YOU GINA!!!! That really brightens the day, and I sooo look forward to chatting with you about American Notes! I’ve been so eager to get to it, too, and am thrilled the timing works out for you on that!

Thanks so much for the prayers 💙 I feel better today than I did yesterday, somewhat, so at least I have (barely) enough of a brain to read and listen to audiobooks 🖤

LikeLiked by 1 person

OMG, Rach–as if you didn’t have enough on your plate already, with your sister’s wedding coming up. Stay safe, relax with a good book (not too difficult for you) and get on the mend. If you’re vaxed you’ll make a speedy recovery. Keep us posted and let us know if there is anything we can do for you. Here’s looking at you, kid!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rach: I’m definitely going to read AMERICAN NOTES. In my Kindle edition of the works of Dickens, there are a few letters that Dickens wrote regarding his voyage to and through America, and these letters, alone, are prompting me to read more about his thoughts about America and Americans (both pro and con–but HEAVILY con). And since CHUZZLEWIT was one of the novels we read in Paul’s seminar, and which I remember very little of, I definitely want to explore that novel more in the context of the NOTES.

I think you and Boze are right; the NOTES will create a very interesting preface to the novel that follows!

P.S. I hope you’re recovering well after your covid “ordeal.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m up to Chapter 68 now.

In our online chat, we talked about why the government (in Barnaby Rudge) isn’t doing more to stop the riots. This week’s reading-or rather this two week’s reading-didn’t take long to answer that question. The Lord Mayor is such a hilariously infuriating character. In contrast to the cowardliness of the authority figures in this part, Dickens shows the heroism of people like the postboy, the vintner, John Grueby, (Has anyone noticed there are a lot of characters named John in this book?) Joe Willet and Edward Chester. (I can’t decide whether Gabriel Varden’s refusal to capitulate to the mob is heroic or quixotic.) As usual, Dickens’s heroes are ordinary everyday people, not superheroes.

The descriptions of the violence of the riots and suffering of Catholics and even some non-Catholics is really powerful. The paint on the house next to the burning Newgate prison “swelling into boils as it were from excess of torture” in Chapter 64 and the details of the doll and the live canaries in Chapter 66 are especially striking. It almost seems wrong to say I enjoyed reading about such terrible things though.

We’ve talked a bit about parallels between the Gordon Riots (as portrayed by Dickens) and the riots in Washington DC in recent American history. That’s what they remind me of too (I’m kind of the one who brought it up) but I have to say they also remind me of riots and looting in certain American cities in the year leading up to January 6 in response to police brutality and racial profiling. I’m not saying hating police brutality or racial profiling is the same as hating Catholics. (I have a cousin who protests against them.) But a mob is a mob and I think that parallel can be justly drawn too.

P.S.

Did anyone else get some Star Wars vibes from Chapter 62? (“I am your father.”) LOL.

P.P.S

I already wrote this on Twitter, but I’d like to send Rachel my sympathies.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aw, thank you so much, Lenny and Stationmaster!!!!! 🖤🖤🖤 Well, I’m not doing bad today, just chills & low energy mostly…but I’ve managed to get a few things done. 🙂 LOVE the Casablanca, Lenny!

I agree, Stationmaster, that this whole sequence in BR is so powerful, and exquisitely written! Loved Varden’s obstinacy, however quixotic, and then Joe and Edward showing up in aid of Haredale!!! I stopped about there, so I’m not sure where this is going, having almost no memory of it.

I also loved your comparisons to Jan 6! I’d read elsewhere that BR is as out of place now as it was in Dickens’ time, but I honestly don’t get that! It is so timely in every way.

LikeLike

I finished the book yesterday!

Although this part of the book features Miggs at her lowest point morally (and Dennis at his), I actually felt a schmeensy bit sorry for her during her rant against Dolly in Chapter 71. I mean it really must be a pain for her to always be kissing up to Mrs. Varden 24/7. Of course, she also still seems to be kissing up to Mrs. Varden during that rant, calling Dolly a “base degenerating daughter” of a “blessed mother as is fit to keep company with holy saints.” But she reveals what she really thinks of Mrs. Varden in her final speech in Chapter 80. I admit I took a perverse pleasure in that one. Kind of wish we had more of her nephew.

It’s interesting that Dickens had Dolly be the one to suspect the women’s “rescuer” even though Emma is the more idealized of the two characters. Then again, Dolly was also the only one to resist John Chester’s manipulation, so it’s not out of character. Maybe Dickens did it to throw his readers off and keep them from suspecting the man’s true identity. It worked for me.

The scene of Gabriel bringing Barnaby home is wonderful. I loved the idea of ending the book (more or less) with a positive mob of sorts and the contrast between Hugh’s fate is memorable. But I’m a bit disappointed Dickens didn’t show us Barnaby’s reunion with his mother. After her sufferings were so vividly portrayed, I would have liked to have seen her relief.

It’s interesting that Dickens ended Geoffrey Haredale’s character on such a dark note when he’d become such a positive figure in the book’s second half. It’s also interesting that he decided to give Grip and his “healing” the last paragraph of the book.

I wrote before that I thought Barnaby Rudge was really underrated but it wasn’t Dickens’s greatest work or anything. Well, now that I’ve read it twice, I’ve decided it’s…well, OK, still not his greatest but definitely one of his greatest. I mean it’s in my top six. That being said, while I remembered the broad plot, I’d forgotten a whole bunch of details from my first read. (Like the revelation about Hugh’s parentage for example.) So maybe it doesn’t have the power to stick in people’s minds like the best of Dickens. I’ll have to see when I read it for the third time.

I’m probably not going to read the American Notes since they’re nonfiction. I’ve read Martin Chuzzlewit and I can’t imagine they’re as entertaining. Maybe if the discussion here is really intriguing. Will I reread Martin Chuzzlewit with the group? I haven’t decided yet. It’s a very interesting book but I didn’t enjoy it nearly as much as I did Martin Chuzzlewit and I feel like it’d be a comedown. But maybe by the time we get to it, I’ll be in the mood. Someday I’ll definitely want to read it again and when I do, I’ll be glad to have the group discussion to guide me.

P. S.

I recently did a brief comedic YouTube video about Dickens. It’s probably too niche for anyone but me to love, but it’s gotten a surprisingly high number of views, albeit not very long ones, and two likes, which obviously isn’t much but is more than I expected it to get. Anyway, I had fun making it and maybe if you guys check it out, you’ll have fun watching it. And if you don’t like the beginning, skip to the David Copperfield or Hard Times moments. Those are the ones that inspired me to make the video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nh8tayBYi7M

LikeLiked by 2 people

Indeed, dear readers, this is a VIOLENT novel. With the coming of Lord Gordon into our little community of characters, we begin to see how the events leading up to the two major conflagrations will sweep the novel’s various characters into the vortex of the riots. And the novel’s violence will meet it’s apex in the three very striking events that are almost too horrendous to witness–the taking apart of Willet’s Maypole, the burning of Haredale’s Warren, and the storming and scorching of Newgate. In each of these upheavals, the novel’s characters that we have come to know so well participate as perpetrators or victims. So, it’s not as though the novel breaks in half–to it’s detriment–as apparently many critics have asserted, but it demonstrates how individuals within a community become involved in a major historical event, are, in effect, subsumed by it. Yes, the novel COULD be defined as a novel solely ABOUT the Gordon Riots, but I think it’s more than that, and that we as a group have displayed the many different ways in which BARNABY exceeds this narrow “definition.”

But keep in mind, that the violence brought about by the riots could be characterized as primarily “physical” violence–the destruction of property and of people–and containing at least a modicum of psychological violence. The Warren is destroyed from top to bottom, from outside to inside, and the same can be said for the Maypole and the Newgate Prison. The psychological dimensions are portrayed mainly in Dickens’ descriptions of the madness of the crowds, their absolutely crazy behavior as they burn and destroy property and, in fact, destroy themselves–throwing themselves into the fire at the Warren, mounting the burning scaffolds at the Prison, and drunkenly ignoring the potential dangers to themselves as the structure of the Maypole begins to disintegrate around them. The physical destruction results, in many instances, in self-destruction. Men are dying as they–in weird psychic frenzies–“attack” these structures. In so doing, they ironically, in many instances, are attacking themselves. In the two conflagrations, there is even a kind of self-immolation! This is scary stuff, and Dickens as a writer, rises to the occasion and describes all this destruction like he’s never done before!

In short, this novel’s apex mesmerizes us with the writer’s harrowing description of “physical” events. But the first 35 chapters of BARNABY are saturated with “psychological” violence. And the effects on the individuals of our little community are extremely devastating. The leading antagonist is Sir John Chester who everywhere puts his “psychic” curse on so many characters–Hugh, Haredale, Edward, Dolly, Emma, Gabriel, Martha, etc., and whose nasty behavior is followed by that of John Willet’s terrible verbal insults and put downs of his son Joe, Martha’s almost sadistic treatment of her husband, Gabriel, and Haredale’s unfeeling response to his daughter’s love of Edward Chester. In contrast to the novel’s later physical violence, the mental violence takes a different toll on the communities’ characters. Each of these victims is scarred in different ways, some more disastrously than others. Thus, I think it’s imperative that we realize that BARNABY need not be characterized solely on the basis of its marvelous presentation of the riots, but also on the in depth portraits of the PSYCHES of its various individuals, before, during and after the riots. In this regard, one might say that the novel is definitely a COHESIVE three part novel, each part being INTEGRAL to the whole. Part 1–the composition of the community; Part 2–the Riots themselves; Part 3–the aftermath of the riots and their effect(s) on the community.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Lenny, I absolutely love the focus on the psychological violence done to our characters in the novel…the precursor to the riots, and the aftermath. I think what is so unfortunate is that the innocent can so easily be the ones to suffer most (Barnaby, his mother…even, in a way, Lord Gordon, as the riots quickly turned into something beyond his control, and don’t seem to have been intended.) One wonders about the trauma the women experienced, and of course Mrs Rudge has had the double-violence of having a murderer husband, and an innocent son caught up in a guilty phenomenon. And the men, too. Joe has lost a limb at least in part because he has been traumatized by a belittling father, and a miscommunication in love. Varden has carried himself well throughout, but his wife has had to have a wake-up call. There is a lot to forgive, even amid the “smaller” and more personal events in the novel. There is reconciliation between Edward Chester and Haredale, but Edward must see now how clearly the faith of his family is viewed by many of the populace, he has a guilty and slain father, a newly-discovered brother, hanged.

I agree with Stationmaster that the “mob” has a different and interesting dimension at the end–but I think that this is again part of Dickens’ critique of the mob mentality…it is fickle/capricious, and is unable to *discern*. So much is “going on” in this novel, and I do love it that, like A Tale of Two Cities, Dickens is able to pull off something at the grand, political/societal scale, but always equally at the human and personal one.

LikeLike

I’m not sure if anyone has mentioned Dickens’s use of the symbolism of water to describe the mob. Most notably in Ch 52 – “A mob is usually a creature of very mysterious existence, particularly in a large city. Where it comes from or whither it goes, few men can tell. Assembling and dispersing with equal suddenness, it is as difficult to follow to its various sources as the sea itself; nor does the parallel stop here, for the ocean is not more fickle and uncertain, more terrible when roused, more unreasonable, or more cruel.” In other words, the mob, like the sea, rises and falls, at times following a tide chart of sorts (the mob tends to rise at dusk and fall by dawn), while at other times being completely unpredictable and springing up like a rogue wave or tsunami, and having very much the same destructive effect.

Other water-related references – the mob is called “this human sea” (35); it “sounded . . . like the roaring of a sea” (48); it “swelled . . . like rivers as they roll towards the sea” (53); from a distance it sounded “not unlike the murmuring in a sea-shell” (54); in the wreckage of Willet’s tavern after it is sacked by the mob “the Maypole peered ruefully in through the broken window, like the bowsprit of a wrecked ship; the ground might have been the bottom of the sea, it was so strewn with precious fragments” (55); surrounded by guards and escorted to Newgate through an ever angrier mob, Barnaby “was tossed about, and beaten to and fro, as though in a tempestuous sea” (58); the mob came “Roaring and chafing like an angry sea” (63); the four condemned men, newly released by the mob, “heaved and gasped for breath, as though in water, when they were first plunged into the crowd” and, after freeing all prisoners, “the human tide had rolled away” (65); it suddenly “rose like a great sea” (67); Hugh, riding bareback on a horse amongst the mob “rolled upon [the horse’s] back . . . like a boat upon the sea” (67); Varden returns home after securing Barnaby’s release “Among a dense mob of persons . . . beating about as though he were struggling with a rough sea” (79).

***

In an interesting parallel to Lord George’s unintended responsibility for the riots is Joe’s unintended responsibility for the attack on Newgate. Before you get upset with me and say, “Not good Joe!”, hear me out.

In Ch 58 we are introduced to Tom Green who “was a gallant, manly, handsome fellow, but he had lost his left arm”. He talks with a serjeant [sic] in Newgate about the prisoners and learns that Grip and Barnaby are among the incarcerated. This news seems to unsettle Tom Green. Then, in Ch 60, a one-armed man, with his face hidden, tells Hugh and the gang that Barnaby is in Newgate, which leads to the storming and burning of the prison. In Ch 64 a one-armed man rescues Gabriel from the mob at Newgate. In Ch 67 Joe, “with an arm the less” helps Haredale and the vintner escape the mob; in Ch 71 Joe helps rescue the girls and restrains Gashford with “his foot . . . in the absence of a spare arm”; and in Ch 72 it is definitively stated, “And Joe had lost an arm – he – that well-made, handsome, gallant fellow!” And so, I think we can conclude that Tom Green and Joe Willet are one in the same and that, inadvertently, Joe is responsible for the attack on Newgate. Granted, I don’t think Joe ever envisioned things would go that far, but then, neither did poor Lord George! I’m wondering what Joe thought Hugh and the mob would do with the information that Barnaby was in Newgate? Did he think they could get Barnaby out without violence? It’s a curious plot twist on Dickens’s part that I don’t quite understand unless he wanted to impress upon us the law of unintended consequences. There are lots of ways Dickens’s could have informed Hugh & the mob about Barnaby’s capture, and lots of ways he could have reintroduced Joe into the story. Thoughts?

***

Rudge’s state of mind while in prison (Ch 62, 65) is very like Bill Sikes’s after killing Nancy – “he was so tortured and tormented, that nothing man has ever done to man in the horrible caprice of power and cruelty, exceeds his self-inflicted punishment” (65).

In Ch 73 regarding the public’s concerned that martial law has been declared – “These terrors being promptly dispelled by a Proclamation declaring that all the rioters in custody would be tried by a special commission in due course of law, a fresh alarm was engendered by its being whispered abroad that French money had been found on some of the rioters, and that the disturbances had been fomented by foreign powers who sought to compass the overthrow and ruin of England. This report, which was strengthened by the diffusion of anonymous hand-bills”. This sound uncannily prescient – ripped from today’s headlines! Special committee to investigate January 6th riot, Russian interference in elections, misinformation spread by “anonymous hand-bills” in place of facebook and twitter.

Fun fact – in Ch 73 Dickens’s tell us “the total loss of property, as estimated by the sufferers, was one hundred and fifty-five thousand pounds” – in today’s US dollars that comes to roughly $30 million!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I didn’t notice the water motif. Thanks for pointing that out. I’d wondered about Dickens’s use of Joe in that part of the story too, but I didn’t ask about it since I was embarrassed to admit I couldn’t understand it. LOL.

I’ve actually thought sometimes that Dickens predicted modern social media culture (not so much with this book as with later ones), but I don’t usually like it when people say that a satirical writer from an age gone by “predicted” something nowadays. I think it’s usually more the case that people have always had the same flaws. We just assume they’re particularly bad in our time since that’s the one in which we’re stuck. Social media really wasn’t around back then though, so maybe we should say it’s an example of the people who would have used social media being the same at heart even without it. Or…something like that. Someone else could articulate it better.

LikeLiked by 2 people

My point was not to say that Dickens actually predicts the future, rather I wanted to point to the idea that through his reporting we find the more things change the more they stay the same.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Exactly. I wasn’t saying you were saying Dickens predicted the culture. I was saying I was tempted to say he predicted it.

If you’re wondering what made me think that, it was actually the next book this group is going to do: Martin Chuzzlewit. Most of its criticisms of America, I think are still reasonable today except that, in my experience, the idea that Americans are obnoxiously patriotic and jingoistic is mostly a stereotype. However, I can understand why people would believe the stereotype when they read angry online comments from Americans who don’t like a bad word said about their country. (In conversation with them, I find the ones who approve of patriotism to still be willing to acknowledge problems with America and to be fairly calm when discoursing about it.) Then it occurred to me that Dickens’s America is a portrait of what the world would be like if everyone talked and acted the way they do on social media! LOL

P.S.

I wrote above that I remember liking Martin Chuzzlewit better than Martin Chuzzlewit. What I meant to write was I remember liking Barnaby Rudge better. Typos are such a pain

LikeLiked by 3 people

Wow, GOOD work Chris! Your sensitive awareness of this water motif really awakened my thoughts about it as I was reading the final chapters of BARNABY last night. Each chapter had at least one key reference to water–either as simile or metaphor. Are we back in the writing lab where Dickens is rapidly hewing his craft to new imaginative heights?

Your excellent analysis also brought me back to the horror of the conflagration of the Warren, the second major destructive moment of the novel–to see to what use Mr. D had made of this water/sea motif, and sure enough there it was–in the midst of all the bright and shiny gore; here’s an opening example where the *visual* of the “crowd’ pouring in “like water” through the various port holes the participants have opened in the Haredale mansion is really effective:

“It was a strong old oaken door, guarded by good bolts and a heavy bar, but it soon went crashing in upon the narrow stairs behind, and made, as it were, a platform to facilitate their tearing up into the rooms above. Almost at the same moment, a dozen other points were forced, and at every one the crowd poured in like water.”

With this simile, the novel captures a visual of the true force and flow of the water moving through various pores struck into the side of the building–yet, as we are reminded by the “like” it’s really a mass of crazed rioters who pour through the various inlets as though the house was really a ship foundering at sea.

And then a bit later, we see not only the destructive mayhem of this crazed group of men, but also the terrible SELF DESTRUCTION that they almost seem to revel in. Although, the carnage takes place in the cellar of the mansion, it again seems as though these terrorists are “working” in the bowels of a ship–into which–men hanging from the upper window sills–are “sucked” as though into a “gulf”–a watery element that resembles the fiery pit of hell:

“Men who had been into the cellars, and had staved the casks, rushed to and fro stark mad, setting fire to all they saw—often to the dresses of their own friends—and kindling the building in so many parts that some had no time for escape, and were seen, with drooping hands and blackened faces, hanging senseless on the window-sills to which they had crawled, until they were sucked and drawn into the burning gulf. The more the fire crackled and raged, the wilder and more cruel the men grew; as though moving in that element they became fiends, and changed their earthly nature for the qualities that give delight in hell.”

Again, later in this horrifying segment of the novel, the “water motif” becomes “frozen”, as though the rioters are participating in this massacre during a snowstorm. The imagery, once again is bizarre and imaginatively drawn out so as to resemble a “winter storm” scene. The visuals are striking and otherworldly:

” the roaring of the angry blaze, so bright and high that it seemed in its rapacity to have swallowed up the very smoke; the living flakes the wind bore rapidly away and hurried on with, like a storm of fiery snow; the noiseless breaking of great beams of wood, which fell like feathers on the heap of ashes, and crumbled in the very act to sparks and powder; ”

We seem to be nearing the end of this particular conflagration and the visual “leftovers” are quite eerie. “Fiery snow” MORPHS into feathers, and again into ash-like snow and finally to powder–as in, perhaps, the visuals after a snowstorm.

And in the waning moments of this spectacle, there are those who seem bent on self-immolation, as they wade into the water-like heat and flames almost voluntarily, suicidal acts that just etch themselves onto the brain of the reader:

“It was not an easy task to draw off such a throng. If Bedlam gates had been flung wide open, there would not have issued forth such maniacs as the frenzy of that night had made. There were men there, who danced and trampled on the beds of flowers as though they trod down human enemies, and wrenched them from the stalks, like savages who twisted human necks. There were men who cast their lighted torches in the air, and suffered them to fall upon their heads and faces, blistering the skin with deep unseemly burns. There were men who rushed up to the fire, and paddled in it with their hands as if in water; and others who were restrained by force from plunging in, to gratify their deadly longing. ”

This is, indeed, crazy stuff happening before our very eyes, as though these crazed individuals were playing at beach games, like small children cavorting among the seaweed and “plunging” pell-mell into the waves of a surf ,paddling to keep their heads above water. But the facts of the matter are far more dire. They are deliberately and literally–“playing with fire”–cavorting around and ultimately “paddling” into and through it–a deadly “game” which will have horrible results.

Up until now–with our reading of BARNABY–I don’t believe we’ve experienced such writing prowess, scenes that are animatedly so alive and stimulating, so visually wrought with details that we can’t help but be carried away, enthralled, and repulsed by such vigorous imagery. This seems like imaginative writing at its best. Thus, I’m wondering if the craft involved in the writing of this “early” novel just sets the bar too high, so that it will be difficult for the other novels to measure up to its imaginative power!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Stationmaster:

Actually, I didn’t see your comments about liking or disliking MARTIN CHUZZLEWIT as *completely* confusing. Either, in my interpretation, you liked the character of Martin or disliked the novel. Or that you liked the novel but not the character of Martin. Oh, well that’s confusing, too. But it still made some kind of sense. In retrospect I could say that I liked OLIVER TWIST–but not so much the presentation of Oliver the character. (Which is kinda MY bias and which would incur the wrath of many other Oliver [the person]devotees!)

In any case I find these kinds of statements really interesting because they hit so perfectly on the concept of “reader response.” For example, to be more in keeping with our present discussion of BARNABY, there seems, historically, to be an abundance of different and widely disparate assessments of this novel. Probably these responses range from it being nearly his WORST novel to something approximating his BEST. I suppose these evaluations serve some kind of purpose, but perhaps are mostly negative in their influences on an abundance of readers. If a critic or literary historian mentions that BARNABY is mostly about the Gordon Riots, then the readership might divide right down the middle. Readers with an historical interest in the periods of “revolution” in British or continental history during the 18th century might decide to read this novel thinking that this is just their “cup of tea.” Whereas the Dickens fan who loves the more Bildungsroman kind of Dickens’ novel might disregard the novel completely because of its historical base. And maybe this kind of critical “cosmos” gets at why so many literary specialists decry the novel–just based on these massive (and influential) critical judgments.

And, as we’ve touched on this discussion before, the *lack* of a well-defined central character who progresses through the novel and carries the weight of the story with him or her–can be quite off-putting. Rachel’s comment about this novel being structured around an ensemble cast seems right on, but her idea might not be acceptable to many readers or critics. As I look ahead to the novels that have their main characters in the TITLE of their narratives, will they necessarily be the STRONG central personality that will carry their narratives. That’s not the case with the title of our present novel. But does this matter? It really might!

Copperfield, Dombey, Chuzzlewit–may appear to hold forth as dominant characters, but will Dickens’ conception of them be enough to carry our enjoyment of the novel. That they are “title” characters might be confusing and misleading. Pip seems to be the most prominent character in GREAT EXPECTATIONS–but he’s not the title character. But could you reasonable title a novel as PIP and attract many readers. There are so many variables here, and they all affect READER RESPONSE. BARNABY RUDGE is a case in point, here!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know I’ve already written about the ending, but I’ve thought of more to say.

It’s interesting that although the ending is generally happy with the bad characters being punished and the good ones rewarded, Dickens stresses that lasting effects of the Gordon Riots with Barnaby being somewhat traumatized for life by them. This is typical of the endings to Dickens’s early novels. They’re mostly happy but he often has the last paragraph be about a sympathetic character who didn’t end well, like Oliver Twist’s mother or Smike in Nicholas Nickleby. Dickens does this (I assume) to avoid the impression that the evils denounced in the stories are something in the past that no longer goes on.

However, even the sober parts of these endings are arguably happy if you pay attention with Dickens insisting that the spirit of Oliver’s mother still lives and the Nicklebys always honoring Smike’s memory. (That’s why I’m not a fan of the last scene of the Nicholas Nickleby stage play. It has the memory of Smike poison the joy.) And while Barnaby may never recover from his trauma, the last paragraph of Barnaby Rudge tells us that Grip eventually recovers from his.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dickens’s ability to keep the action moving while giving minute detail of what is happening is so worthy of study. His reporter’s eye catches everything as his skill at maintaining and/or heightening pace channels it all to great effect. Take for example this passage from Ch 64 as the fire at Newgate is set (emphasis added):

“At first, they crowded around the blaze, and vented their exultation only in their looks: but WHEN it grew hotter and fiercer – WHEN it crackled, leaped, and roared, like a great furnace – WHEN it shone upon the opposite houses, and lighted up not only the pale and wondering faces at the windows, but the inmost corners of each habitation – WHEN, through the deep red heat and glow, the fire was seen sporting and toying with the door, now clinging to its obdurate surface, now gliding off with fierce inconstancy and soaring high into the sky, anon returning to fold it in its burning grasp and lure it to its ruin – WHEN it shone and gleamed so brightly that the church clock of St. Sepulchre’s, so often point to the hour of death, was legible as in broad day, and the vane upon its steeple-top glittered in the unwonted light like something richly jeweled – WHEN blackened stone and sombre brick grew ruddy in the deep reflection, and windows shone like burnished gold, dotting the longest distance in the fiery vista with their specks of brightness – WHEN wall and tower, and roof and chimney-stack, seemed drunk, and in the flickering glare appeared to reel and stagger – WHEN scores of objects, never seen before, burst out upon the view, and things the most familiar put on some new aspect – THEN the mob began to join the whirl, and with loud yells, and shouts, and clamour, such as happily is seldom heard, bestirred themselves to feed the fire, and keep it at its height.”

The scene is of a very brief space of time, yet each “WHEN” points out another thing that is happening in that moment, and the dashes act like one’s eyes scanning the scene from detail to detail. We watch the fire as it builds and progresses, “THEN” we see the effect of all these “WHEN’s” on the mob and understand their response because of this build-up.

Similarly, the ending of Ch 68, encompassing the four paragraphs, “He looked back . . . in the still country roads”, gives us Barnaby’s “last glance” as he pulls the injured Hugh away from the mob burning the vintner’s house. This glance takes in a myriad of horrors that become “fixed indelibly upon his mind” as on that of the reader’s. Again, a brief space of time is filled to the brim with detail and description which, in my opinion, is the beauty of Dickens.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Chris–more wonderful analysis which captures Dickens’ eye for detail and his uncanny ability to record the mood of this crowd. In this case, it’s as though he, the writer, is scanning this scene with a video camera, panning from one segment to another to share with his readers the awfulness of what is going on before us.

This is the 2nd “conflagration” sequence and it follows beautifully but terribly on the first–which I’ve just spoken of (above)–and which takes place at the Warren. The next will be at the wine merchants–adding to an abundance of horror that the writer doesn’t want us to forget!

LikeLiked by 1 person

What wonderful reflections on Barnaby, friends! I just have to say, I loved that Chris pointed out the water motif–because we’ll see this again in Barnaby’s “sister-novel,” A Tale of Two Cities, and Dickens will use “the sea rises” and its watery/deluge imagery for the storming of the Bastille and the movement of the mob there, as well!

On another note, I’m so, so glad that others here too (Lenny, Chris, Dana, Daniel, Gina–possibly Stationmaster?) will be reading American Notes. Boy, does Dickens really nail us on so many points! I’ve also been seeing some of the influence of his wonderful career as a sketch writer here–it is really paying off in his recreation of his trip and his uniquely *Dickensian* observations. Boze and I have been reading it aloud chapter by chapter, and it is just fantastic, & I think will be really interesting to read side-by-side with Martin Chuzzlewit!

LikeLike