WHEREIN WE REVISIT OUR third and fourth WEEK’S READING OF Bleak House (WEEKs 78-79 OF THE DICKENS CHRONOLOGICAL READING CLUB 2022-24); WITH A CHAPTER SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION WRAP-UP; CONTAINING A LOOK-AHEAD TO WEEKs five and six.

(Banner image: by Fred Barnard. Scanned image by Philip V. Allingham.)

By the members of the Dickens Club, edited/compiled by Rach

Friends, what amazing chapters we’ve tackled together over the past two weeks! Esther’s parentage has been revealed, and the rag-and-bottle-shop secret keeper, Krook, has become nothing more than a mass of flesh and flame in one of the most deliciously disturbing and grotesque passages in literature.

We’ve covered so much ground in our discussion. First, however, a few quick links:

- General Mems

- Bleak House, Chs 17-32 (Weeks 3 & 4): A Summary

- Discussion Wrap-Up (Weeks 3 & 4)

- A Look-Ahead to Weeks 5 & 6 of Bleak House (11-24 July, 2023)

General Mems

SAVE THE DATE: Join us for our online discussion of Bleak House! Saturday, 12 August, 11am Pacific (US)/2pm Eastern (US)/7pm GMT (London)! Please feel free to message Rach here on the site, or on twitter, to get on the list for the Zoom link that she’ll send out in early-August.

If you’re counting, today is Day 553 (and week 80) in our #DickensClub! This week and next we’ll be on Weeks 5 and 6 of Bleak House, our eighteenth read of the group. Please feel free to comment below this post for the fifth and sixth week’s chapters, or use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter.

No matter where you’re at in the reading process, a huge “thank you” for reading along with us. Heartfelt thanks to our dear Dickens Fellowship, The Dickens Society, and the Charles Dickens Letters Project for retweets, and to all those liking, sharing, and encouraging our Club, including Gina Dalfonzo, Dr. Christian Lehmann and Dr. Pete Orford. Huge “thank you” also to The Circumlocution Office (on twitter also!) for providing such a marvelous online resource for us.

And for any more recent members or for those who might be interested in joining: the revised two-and-a-half year reading schedule can be found here. For Boze’s marvelous introduction to Bleak House and for our reading schedule, please click here. For Chris’s supplementary intro reading material, please click here. If you’ve been reading along with us but aren’t yet on the Member List, we would love to add you! Please feel free to message Rach here on the site, or on twitter.

Bleak House, Chs 17-32 (Weeks 3 & 4): A Summary

(Note: The below illustrations are by “Phiz,” Hablot Knight Browne, from the original edition, and have been downloaded from the marvelous Charles Dickens Illustrated Gallery. Thank you!)

Mr and Mrs Badger acknowledge to Esther, responding to her concern, that Richard’s vocation might not lie in the medical field; Esther speaks to Richard and he agrees with their assessment. He’d prefer to try law. Ada is deeply supportive, but is doubtful about the law because of the cloud of Chancery. Jarndyce too is supportive, but expresses his concern for Ada in regards to Richard’s changes of mind.

Both Esther and Jarndyce are awake late, disturbed by forebodings and private thoughts. Jarndyce has been disturbed by something that she would not “readily understand.” Jarndyce tells her of how he came to be her guardian, having been solicited in a letter from a woman—Esther’s guardian/godmother—who begged him to take over Esther’s care if anything should happen to her. This aunt, with a “distorted religion that clouded her mind,” verbally abused the child Esther, saying that Esther’s mother was her disgrace, and vice-versa. As she wanted to remain anonymous, Mr Kenge became the go-between.

Then, just as Alan Woodcourt is about to depart as a ship’s physician, being bound on a long journey, Esther is introduced to his mother, who, though not wealthy, is of noble Welsh birth, and values birth above all. Caddy later brings Esther a bouquet of flowers from Mr. Woodcourt.

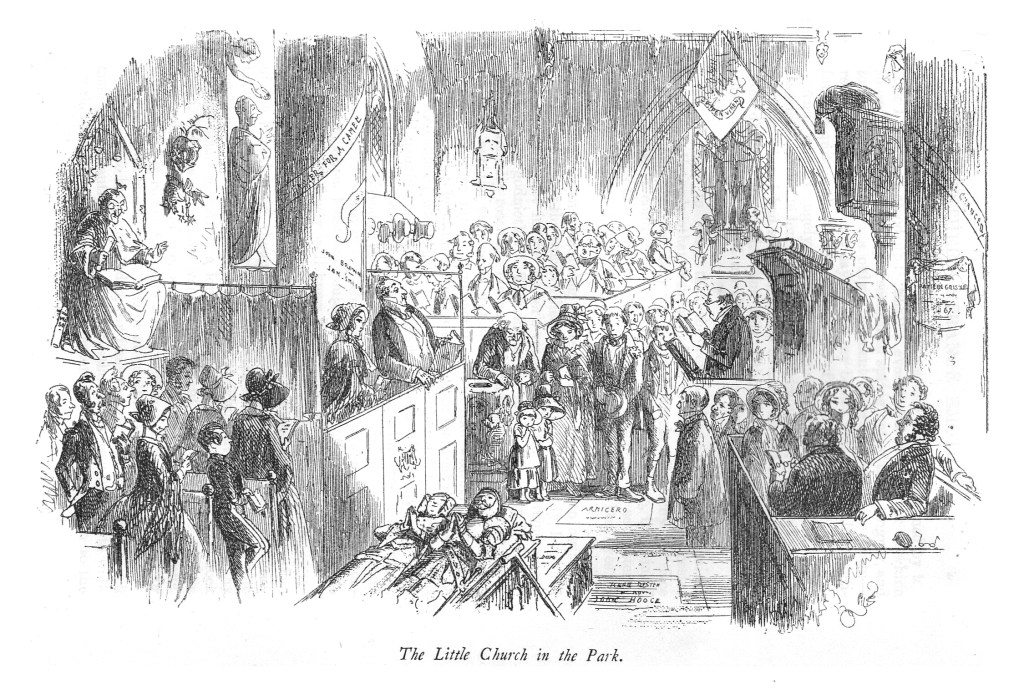

Jarndyce, Ada, Esther, and Mr Skimpole visit their friend Mr Boythorn, who verbally thrashes Sir Leicester Dedlock. At church, Esther gets a glimpse of Lady Dedlock, and is unaccountably moved; she sees Lady Dedlock closer, and is formally introduced to her, when they—and Jarndyce and Ada—were caught in the rain and took shelter in a covered lodge in the woods near the Dedlock grounds. An odd scene ensues, where a messenger had been sent for a carriage by Lady Dedlock, with instructions to bring her maid, but both Rosa and Hortense (the French maid) come; Lady Dedlock informs Hortense that she did mean Rosa, and not her—at which, after the carriage drives off, Hortense expresses her indignation and then “slipped off her shoes, left them on the ground, and walked deliberately in the same direction [as the carriage], through the wettest of the wet grass.”

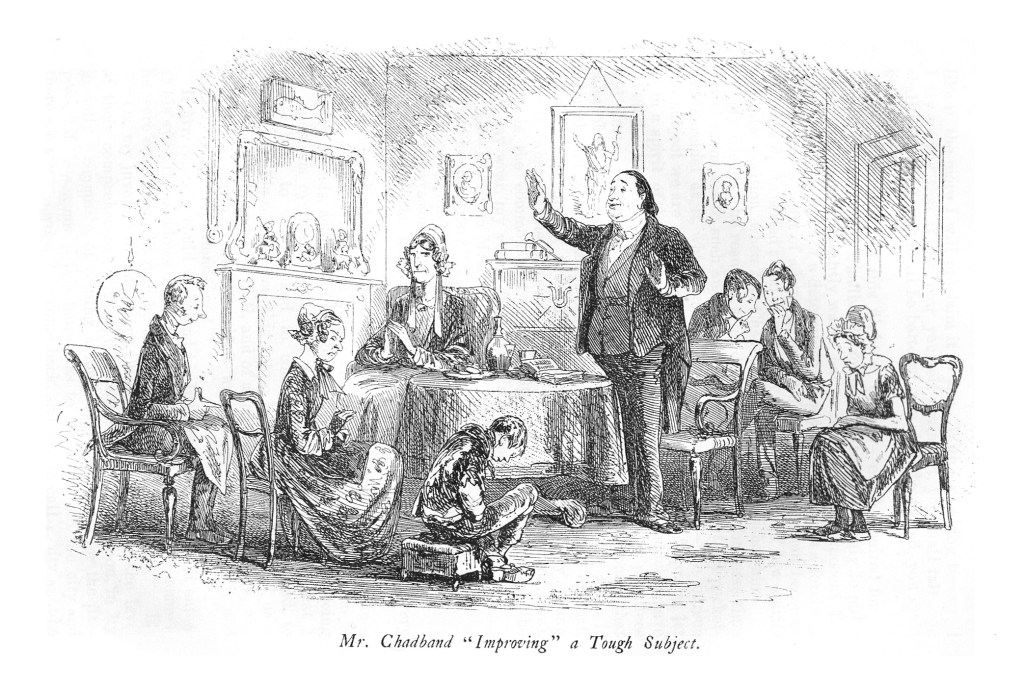

We learn, through the means of a dinner at the Snagsbys’ home to which Mr and Mrs Chadband—and Mr Chadband’s eloquence–arrive, that Jo has been seen hanging around Mr Snagsby’s work and was nearly arrested for loitering, but that Mr Snagsby had vouched for him. But still, Jo was told to “move on”—with a bit of food that Mr Snagsby had gotten for him. Mr Guppy enters the scene, and learns that the Chadbands had briefly been the guardians of Esther Summerson, and had treated her like a servant. Guppy learns of a connection between Esther and a “Miss Barbary”—Esther’s godmother.

Meanwhile, having a lull in work during the summer vacation while showing Richard the ropes at Kenge & Carboy, Guppy also employs Mr Jobling to keep an eye on Mr Krook for the benefit of himself and Smallweed. They’re sure that Krook knows something about Jarndyce and Jarndyce, being such a collector of documents and information. Afterwards, plying Krook with more drink, Jobling is accepted (going by the name of Weevle) as a tenant.

Mr George, feeling threatened by certain conditions put upon him by his debts to Smallweed, pays a visit to the Smallweed home, where he also encounters the teenage but too-old-hearted Judy. George refuses to tell him the names of those who would be responsible for the debts if George couldn’t pay them. When George returns to his failing business, a shooting gallery, he has some conversation with his poor assistant, Phil.

Meanwhile, Snagsby gives Tulkinghorn and Inspector Bucket information about how Jo claims to have come by the two sovereigns, and they hear the account of the mysterious lady who had inquired about Nemo’s residence and burial place. Bucket and Snagsby seek out Jo at Tom-all-Alone’s, where they encounter Jenny, the bricklayer’s wife who had been treated kindly by Esther, who is helping to care for a child, having lost her own. Jo, though fearful, allows himself to be taken to Mr Tulkinghorn’s office for questioning – there, in a disguise like that of the mysterious woman, Hortense comes in, causing Jo to yell in fear. But when her hand is revealed to him and she comes closer, Jo realizes that it is not the same woman. Jo is allowed to leave, having been given five shillings.

While still on an extended stay at Boythorn’s, Esther receives a strange request from the strange attendant, Hortense, who has been out of favor with Lady Dedlock: Hortense wishes to be Esther’s maid. Esther cannot accept the offer. After returning to Bleak House, Esther then visits Richard in London; she is concerned about him, and it proves to be well-founded, as he is unable to bring himself to stick to his employment and is considering joining the army. The indecisive, unending Chancery case weighs on his mind constantly, making him unable to adhere to anything.

Esther’s presence is required at two momentous interviews with Caddy Jellyby—regarding Caddy’s engagement to Prince Turveydrop. Both Mr Turveydrop and Mrs Jellyby come round to accept the situation: Mr Turveydrop is comforted by the knowledge that he’ll have two people to look out for him, and Mrs Jellyby, so distracted by her long-distance philanthropic work, she can barely spare the time to consider Caddy’s situation overmuch anyway.

Meanwhile, Richard’s financial and employment situation is growing worse, inducing Mr Jarndyce to intervene with conditions regarding his change—again—of vocation; one of them is that he will break off his engagement with Ada until he is financially settled. He is training with Mr George in order to assist him in his new chosen career. John Jarndyce also advises Richard not to pin his hopes on Chancery—indeed, one is better off dead than to do so. Richard’s unacknowledged distrust of Jarndyce begins to emerge, as he sees Jarndyce as holding out on him in regards to the Chancery case—and a rival.

While Rick and Esther attend a court hearing about Jarndyce & Jarndyce, they encounter Mrs Chadband—formerly a servant at Esther’s godmother’s—and then Mr George. Miss Flite needs escorting to George’s shooting gallery, where Mr Gridley is in hiding from the law. John Jarndyce arrives shortly after, as does Inspector Bucket, who has been pursuing Gridley. Bucket arrives, disguised as a doctor to attend upon Gridley. Once the truth is revealed, Bucket agrees to give Gridley, who is dying, a moment with his old friend Miss Flite—the only thing that Chancery has left him in his long struggle. Gridley dies, defeated by Chancery.

Meanwhile, Mrs Snagsby has become suspicious of her husband and her husband’s kindliness towards Jo, and spies on the former. Jo ends up falling asleep at a sermon of Chadband’s when dragged into the Snagsbys’ home. Later, Snagsby and their servant Guster help Jo to a little food and money before he goes on his way.

Meanwhile, George has reluctantly agreed to his creditor Smallweed’s request that he bring some papers of his old friend, Captain Hawdon, to an associate of his, who turns out to be Mr Tulkinghorn. Once there, George declines to help assisting them in seeing Hawdon’s papers—to verify the dead man’s identity—until he has been able to consult a friend.

George consults his friend, Mr Bagnet, over dinner at Bagnet’s home. Mrs Bagnet is, in reality, the head of the household, and advises George that he have nothing to do with Smallweed and Tulkinghorn. George reiterates this decision to Tulkinghorn, who hints the rebuke that George had harbored the “dangerous” Gridley.

In the midst of visits from impecunious relations to the Dedlocks—including Volumnia—Sir Leicester and Lady Dedlock are visited by one of Mrs Rouncewell’s sons, the “ironmaster” who has done well for himself. Mr Rouncewell has requested the interview because his son is in love with Lady Dedlock’s maid, Rosa, and Rouncewell doesn’t see Chesney Wold as a place suitable for a wife of his son’s to stay indefinitely, as his son has been well brought up and educated. This incurs the indignation of Sir Leicester, and Rouncewell says he will try to help his son conquer his inclinations. Lady Dedlock later approaches Rosa tenderly about the subject; Rosa cares for the son but also doesn’t want to leave Lady Dedlock as yet; Lady Dedlock’s motherly feelings come out with Rosa; she wants to assist Rosa’s happiness, but also doesn’t want to give her up yet.

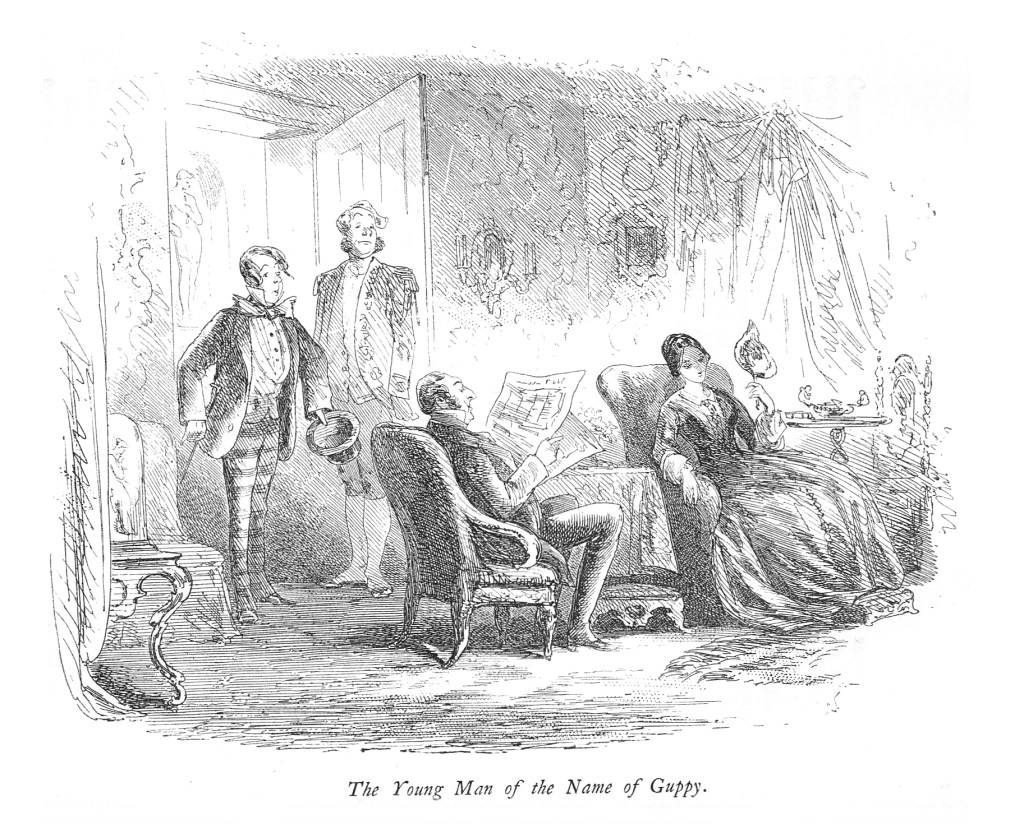

Meanwhile, Guppy has continued his investigations into Esther’s parentage, hoping, perhaps, to establish a link between Esther and the case of Jarndyce & Jarndyce, and seeing the resemblance between Esther and Lady Dedlock. Guppy visits Lady Dedlock, who, without betraying any emotion, becomes immediately interested in what Guppy has to say: the likeness between Lady Dedlock and Esther; that Esther was under the care of a Miss Barbary; that Esther’s correct surname is Hawdon. Guppy hopes that Lady Dedlock might be interested in the private papers of Captain Hawdon, currently in the possession of Krook—and she gives Guppy permission to try and acquire these papers.

Unspoken to Guppy, the truth of the situation his home to Lady Dedlock: Esther is her own daughter.

Meanwhile, Esther must suffer the slings and arrows of Mrs Woodcourt’s comments and aspirations for her son’s future wife, while Mrs Woodcourt is on an extended stay at Bleak House. Shortly after, Caddy pays a visit about her upcoming marriage and the hopes that Ada and Esther will be bridesmaids. The young women invite Caddy to stay at Bleak House to help Caddy prepare her dress and other necessaries before the wedding, then help to prepare her mother’s home in preparation of the big day.

Esther and Charley visit Jenny, the bricklayer’s wife, who had been nursing a sick boy—who turns out to be Jo. At first, Jo is frightened at seeing Esther, thinking in his semi-delirium that Esther is the mysterious, veiled woman who gave him the sovereigns and has unwittingly caused him so much hassle. Finally being convinced, however, that she is not, he accompanies Esther and Charley to Bleak House—since Jenny’s husband will not abide him to remain there—for shelter. Skimpole advises against it, as his very brief history in the medical profession taught him enough to know that there is a contagion about Jo.

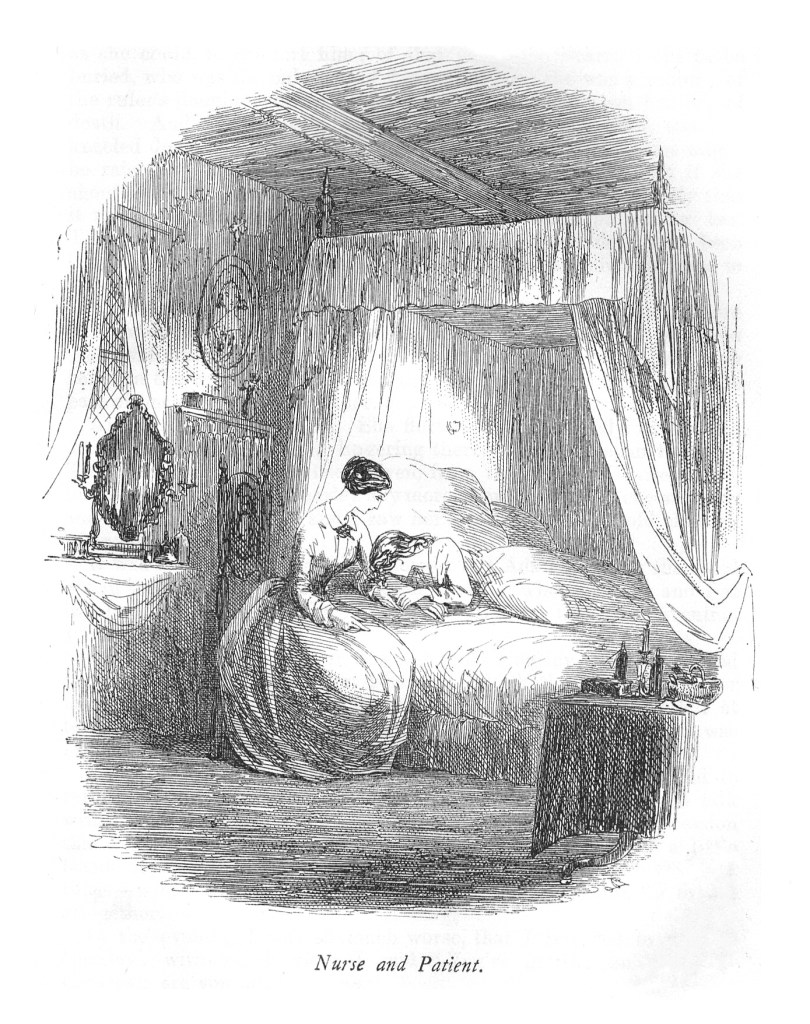

Jo goes mysteriously missing the following morning. Charley becomes ill from the same illness that Jo had–the smallpox–and while nursing Charley, Esther herself becomes gravely ill. Charley, once recovered, nurses Esther so that the contagion will not spread to anyone who has not already been exposed.

“It’s far from a pleasant thing to be plotting about a dead man in the room where he died, especially when you happen to live in it.”

Mr Weevle, aka Jobling, who has been occupying Nemo’s old room for the purposes of spying, is uncomfortable with staying in the room of a dead man. But while Guppy is in Weevle’s room, they both notice a stale, greasy something on the air, and something causing stains on Guppy’s sleeve. Intending to meet with Krook about the papers of Hawdon’s that Krook has been illegally keeping, they go down to discover that Krook is not there—or rather, that all that is left of him is a mass of foul-smelling flesh and flame. He has been a victim of that rare phenomenon, spontaneous human combustion.

“Here is a small burnt patch of flooring; here is the tinder from a little bundle of burnt paper, but not so light as usual, seeming to be steeped in something; and here is—is it the cinder of a small charred and broken log of wood sprinkled with white ashes, or is it coal? Oh, horror, he IS here! And this from which we run away, striking out the light and overturning one another into the street, is all that represents him.

Help, help, help! Come into this house for heaven’s sake! Plenty will come in, but none can help. The Lord Chancellor of that court, true to his title in his last act, has died the death of all lord chancellors in all courts and of all authorities in all places under all names soever, where false pretences are made, and where injustice is done. Call the death by any name your Highness will, attribute it to whom you will, or say it might have been prevented how you will, it is the same death eternally—inborn, inbred, engendered in the corrupted humours of the vicious body itself, and that only—spontaneous combustion, and none other of all the deaths that can be died.”

Discussion Wrap-Up (Weeks 3 & 4)

Whimsy & What We Loved: Guppy’s Proposal; Appreciation for Comments on Weeks 1 & 2; Mrs Bagnet; Chadband; Comedy in Bleak House

And while everyone is tweeting silly memes about the fact that the Barbie movie & Oppenheimer premiere on the same weekend, why not add a Dickensian one?

But you know what we really loved? GUPPY’S PROPOSAL TO ESTHER! Jacquelyn writes:

Daniel agrees:

Daniel also expressed appreciation for Rob’s comments on the “battlefield” of Jarndyce and Jarndyce, of the group’s idea that we are all “detectives” on the case that is Bleak House, of Chris’s marvelous comments and the essay on the proposal of Esther-as-both-narrators, and Jacquelyn’s comments on telescopic philanthropy, adding to the latter:

“Thanks much to you, Jacquelyn, for your thoughts about this troubling phenomenon [of telescopic philanthropy]. One thought that occurred to me is that women such as Mrs. Jellyby and Mrs. Pardiggle were women who aspired to greater influence on society than they could exert as mothers. This possible chafing at their lack of access to positions of power and influence might have been channeled into their skewed attempts to benefit those at a distance while so evidently disregarding their nearest and dearest.”

~Daniel M. comment

The Stationmaster expresses his appreciation for Mrs Bagnet:

And I am personally ready to start speaking in Chadbandisms, to the annoyance of all:

And the Stationmaster shows appreciation for the brilliant comedy in Bleak House:

The Omnicient Mystery-Narrator In Bleak House: Esther? John Jarndyce? Just…Dickens Himself?

SPOILER ALERT: If you know the plot of Bleak House, please check out Chris’ masterful analysis of the theory that Esther is also the mysterious omniscient narrator of the novel’s other half.

I will quote from her summation here, without spoilers:

“While the idea that Esther may also be the writer of the TPON is tantalizing, after reading these arguments I’m remain unconvinced that she and the TPON are one entity. While I understand Hornback’s and Schor’s arguments about how tying the two narratives together might give greater agency to Esther’s Voice, I have some difficulty believing Esther capable of writing some portions of the TPON’s narrative. For example, I’m unconvinced Esther has the necessary grasp of the workings of Chancery or the legal profession to write the sections of the novel that sharply and pointedly critique them, or that she could conceive the thoughts or callousness of Mr Tulkinghorn, or treat her father’s death with the stoic distance of Chs. 10 and 11. And I wonder why the bulk of Esther’s anger should be directed toward her mother, and not toward her aunt who is really the architect of her sad story. Further, Schor’s argument is so weighted in modern Feminist perspectives that I have trouble imagining Dickens’s sensibilities being such that he would make them the basis of an entire novel.”

~Chris M. comment

The Stationmaster responds:

“I don’t buy Hornback’s analysis that the third person narrator voice is how Esther vents her anger. At the beginning of the book, I might have bought into that. But the third person narrator also ends up describing characters whom Esther likes and respects, mainly George and the Bagnets. It also describes characters who are bad, like the Smallweeds, but with whom Esther has a less personal reason to be angry. For that matter, the narrator who is unambiguously Esther describes characters and things that make her angry, mainly Skimpole, Mr. Turveydrop and Mrs. Jellyby. I think the simplest explanation, that the third person narrator is used for describing things Esther doesn’t witness, is the best.”

~Adaptation Stationmaster comment

He is intrigued by my thought from last week that, if the omniscient mystery-narrator is indeed someone we know, it is likeliest to be John Jarndyce:

Dickens’s “Writing Lab”: Characterization & the Astute “Psychological Portraits”; Doubling (Judy/Esther); Dickens Writing “On the Edge of Fantasy”

The Stationmaster shares very insightful comments about Gridley, a possible negative comment about Nemo based on how we interpret a comment of Lady Dedlock’s to Rosa, the products of “charitable schools,” and the fascinating idea of Judy as foil to Esther:

Lenny responds:

Lucy responds, giving a marvelous summation of the many examples of doubling going on in this novel:

Chris comments on the marvelous characterization, and questions the judgement of Mr Jarndyce:

Lenny writes of the wonderful “confrontations…fraught with tension” that occur between Guppy and Lady Dedlock:

Henry, on twitter, writes of the narration in Bleak House, “the skulking atmosphere; the brisk, contorted prose; the perpetual sense of someone lurking.” He writes, Henry says, almost “on the edge of fantasy.” Please click the link to his twitter comment below to read the full thread:

Character Spotlight: the Problem of Richard; Esther as Observer

The Stationmaster writes of a passage of Esther’s narration about Richard’s “dazzling” qualities which have not served him well:

Jacquelyn writes of Richard’s “fatal flaw” and the power of Esther’s observation:

Lenny agrees:

Though I might have placed Rob’s insightful analysis of the pairing of Caddy and Richard in the Writing Lab/Doubling section, I place it here, as it illuminates much about the “problem” of Richard:

Does it come down to “responsibility vs. “irresponsibility”? Lenny loves this pairing of two very different characters and their trajectories:

Rob adds:

Chris writes on Richard, and the other bit of doubling: Richard/Gridley.

Esther and the Smallpox

Lucy writes of the emphasis on Esther‘s getting the smallpox, and what it would have meant, socially, for a young Victorian woman:

Was it possible that Woodcourt had been inoculated against it? Rob writes:

Lenny takes this whole section of proof of Esther’s heroism, her continual thought about and concern for the other, rather than for herself:

Responsibility and Debt (Continued from Weeks 1 & 2)

Though we’ve touched on irresponsibility vs. responsibility in the portion on Richard, Daniel sums up the theme so well here:

Dickens on Chancery: Impenetrable Fog; Spontaneous Combustion

The fog of Chancery is pervasive from the beginning. Daniel writes:

But is Chancery not only impenetrably convoluted, but ready to ignite from within?

Dickens went there: spontaneous combustion. And who doesn’t love that grotesque scene with Guppy and Weevle discovering Krook’s near-unrecognizable remains in Chapter 32?

The Stationmaster writes:

Lucy shares in the love:

Boze looks at it in a larger context:

Besides being a little too full of enthroosymoosy for that scene, I am intrigued by the narrative change, a voice Dickens has employed before, in the Sketches:

The “Reader” in Bleak House; the Reader as “Detective”; Inspector Bucket; Complexities and Interconnectedness; Or, the Fog Pervades Our Reading, Too

Chris expresses her appreciation for Inspector Bucket–he knows just how to cajole and flatter; he knows how to get the information he needs.

But as we’ve discussed from the beginning, Dickens has set up the reader as detective–we might often feel ourselves as much in the fog as anyone in the novel. Lenny appreciates the insights of the group for just this reason:

Rob compares the reader’s confusion to that of Snagsby, and we hope that Inspector Bucket pulls it all together for us!

A Look-Ahead to Weeks 5 & 6 of Bleak House (11-24 July, 2023)

This week and next we’ll be reading Chapters 33-49, which constitute the monthly installments XI-XV, published between January and May 1853. Feel free to comment below with your thoughts, or use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter.

I read ahead over the weekend a bit. That’s why I’m doing this super long comment right away.

I love the line about Cook’s Court being like “a court that has had a little money left it unexpectedly” on the night of Krook’s death.

The 2005 miniseries adaptation of Bleak House combines the characters of William Guppy and Tony Jobling into one. (The 1982 one might too. I only watched that one once a long time ago.) Personally, I used to think that was a good decision. Tony Jobling is a well written character, but I find the whole device of Guppy interrogating Krook through him rather overcomplicated. However, the bit where Guppy casually tries to convince the traumatized and exasperated Jobling that he should stay at Krook’s after the man’s gruesome death is hilarious enough to make me second guess my opinion.

Dickens sure was defensive about the believability of spontaneous combustion, wasn’t he? He even went as far as to satirize naysayers in the text itself.

Most of the comments here have been pretty pro-Esther, so I feel a little nervous criticizing her narration, but Chapter 35 has a great example of what distracts me about it.

“Perhaps the less I say of these sick experiences, the less tedious and the more intelligible I shall be. I do not recall them to make others unhappy or because I am now the least unhappy in remembering them. It may be that if we knew more of such strange afflictions, we might be the better able to alleviate their intensity.”

If I didn’t want to read about a character suffering, I wouldn’t pick up a book titled Bleak House. You don’t have to apologize, Esther! Go ahead and wallow in your misery for us.

Which is too bad since most of Chapters 35 and 36 are awesome IMO. They’re the part of the book where it really becomes clear why Dickens chose to have us experience the story through Esther’s eyes. So much of it is about her personal feelings. I love the depiction of how she feels like “a child, an elder girl and the little woman I had been so happy as” at the same time during her illness, her rapturous relief at getting her sight back, her lingering regret and anxiety over her ruined face and her attempts to talk herself out them.

I also love the scene where Miss Flite reveals her backstory and that she’s not the crazy Chancery fangirl she seems to be, how she’s aware that it’s no good attending court all the time but “there’s a dreadful attraction in the place.” I wrote before how so many characters in David Copperfield turned out to be more complex than they seemed at first. It’s not as big a theme in Bleak House but it’s still there, mainly with the reveals in Chapters 35 and 36 of what lies behind Miss Flite and Lady Dedlock’s facades.

Esther the narrator gets one of the sickest burns in Dickens in response to Miss Flite’s contention that “all the greatest ornaments of England in knowledge, imagination, active humanity, and improvement of every sort are added to its nobility!”

“I am afraid she believed what she said, for there were moments when she was very mad indeed.”

That’s hilarious but it’s rather odd coming from Esther. Should we take it as an indication that she has a well suppressed snarky side? Does it add depth to her personality? Or is it a technical flaw, Dickens’s voice overriding the character’s? I love the line, so I’m going to go with the “added depth” interpretation though I fear “technical flaw” is closer to the mark.

I thought about commenting on this before, but I decided to wait until now. I don’t think it pays off to have Esther be so embarrassed to write about her feelings for Allan Woodcourt. It was funny but the lack of any real description of him or of any dialogue between them made it impossible to care until this point. Even when they reunite, it feels like we don’t really get to know him for a while, which is too bad because the broad outlines of their love story are one of the most romantic things in Dickens. I don’t blame Esther for not wanting to write about something so personal, but in that case, why is she writing this book at all?

The scene between Lady Dedlock and Esther in Chapter 36 definitely ranks among the most powerful in Dickens. It’s arguably unusual for him in that, in its painful way, it’s an uplifting exchange between a mother and a daughter. While Dickens typically implied that his heroes and heroines became good fathers and mothers after the events of their stories, the majority of the parents he depicted were abusive, exploitative, embarrassing or all of the above. Even when he had positive parent characters, such as Mr. and Mrs. Cratchit in A Christmas Carol or Mr. and Mrs. Bagnet in this book, their relationships with their children weren’t explored much. Lady Dedlock isn’t exactly a good parent, she hasn’t really had a chance to do much parenting, but she’s not abusive, exploitative or embarrassing. (Well, she is “embarrassing” to Esther in that she had her out of wedlock, but she clearly feels terrible about that. She’s not obliviously embarrassing like, say, Mrs. Nickleby or Mrs. Jellyby.)

There’s something potentially disturbing about the scene which Linda M, Lewis points out though. While Esther says she’ll never desert her mother, she doesn’t encourage her to seek God’s forgiveness. The closest she comes is suggesting she lie her cards on the table with Tulkinghorn or Mr. Jarndyce. Contrast this with Rose Maylie’s interactions with Nancy in Oliver Twist. (“It is never too late for penitence and atonement.”) Could it be that because of her upbringing Esther doesn’t believe there is forgiveness in Heaven for her mother? That’s depressing.

One of Dickens’s goals in his books was to convince society to give women who had sex out of marriage the benefit of the doubt. (He was involved with Urania Cottage which was for rehabilitating such women.) He portrayed women such as Nancy, Emily and Martha in David Copperfield and that character from The Chimes whose name I can’t remember, as being guilt stricken and miserable and generally the victim of their male lovers. With Lady Dedlock, he took a more challenging approach. At first, she doesn’t seem like she’s suffering any consequences for her actions. There’s little or no reason to call her Capt. Hawdon’s victim and her personality type seems to be that of an arrogant gold digger. Rather than coming across as penitent (at first), she’s conned Sir. Leicester and society, marrying him on the clear understanding that she’s a virgin when she’s not. She’s even rather snobbish to Jo, which Dickens didn’t have to have her for the plot to work. The pain she feels, and her sympathetic character qualities are revealed to the reader gradually. But when they’re finally all transparent, the contrast with our previous view of her makes them really pack an emotional punch. The risks Dickens took with Lady Dedlock pay off.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I’m a more ardent fan of David Copperfield than I am of Bleak House but something I feel the latter portrays more powerfully than the former is the experience of watching someone you love go down a dark path and not being able to stop them. With Steerforth, it was pretty obvious from the start that he was no good and we pitied David his disillusionment but couldn’t relate to it ourselves. With Richard, I think we feel more what Esther, Ada and Jarndyce are feeling toward him.

I love this description of Guppy’s portrait. It “was more like than life: it insisted upon him with such obstinacy and was so determined not to let him off.”

The scene between Vholes and Richard in Chapter 39 is interesting in that it’s the only scene where the third person narrator depicts Richard in detail. (Correct me if I’m wrong about that.) Since he’s not in Esther or Ada’s presence, we see him be much more open about his resentment of John Jarndyce. We also see more how Vholes, a great evil character manipulates him. We should really make a list of which characters our only shown through Esther’s eyes, which are only shown through those of the other narrator and which are shown from both perspectives.

Dickens wants us to be angry at how Vholes uses his three daughters and father to make people feel sorry him and for the most part I am angry, but I have to say his description of the family’s living quarters (“an earthy cottage situated in a damp garden at Kennington”) does sound pretty miserable. I’d want to make more money if I were him too.

For all that Guppy is a jerk, I kind of admire him for not cracking even more under Tulkinghorn’s gaze in Chapter 39.

I love this part of Chapter 40. “This stupendous national calamity, however, was averted by Lord Coodle’s making the timely discovery that if in the heat of debate he had said that he scorned and despised the whole ignoble career of Sir Thomas Doodle, he had merely meant to say that party differences should never induce him to withhold from it the tribute of his warmest admiration; while it as opportunely turned out, on the other hand, that Sir Thomas Doodle had in his own bosom expressly booked Lord Coodle to go down to posterity as the mirror of virtue and honour.” Definitely captures how insincere public apologies sound.

Can someone tell me what the gun firing close by in Chapter 40 is supposed to be? I know its purpose in the scene is to set up Lady Dedlock’s allusion to Hamlet and Polonius but…what was it supposed to actually be? Was it just someone hunting outside? If so, why was Volumnia so startled by it?

It’s interesting (to me) that Tulkinghorn speaks of Sir Leicester “unconsciously carrying the matter with so high a hand.” That negatively charged phrase makes it sound like, for all his talk of loyal he is to Sir Leicester’s interests, he really resents him and wants some kind of revenge.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Stationmaster: good grief, you have so many ideas bouncing around in this post, that I’ve been thinking about all of them and wanting to comment on each. But for now, I’m selecting this one particular quote as I find it’s particularly interesting not just for our views of characters in BLEAK HOUSE but for characters in most of the other novels we’ve been reading. Here’s your fascinating quote:

“…the experience of watching someone you love go down a dark path and not being able to stop them.”

Certainly it applies hugely to Richard in our present novel. His slow movement toward being wholly swallowed by the doings at Chancery is just so sad and frustrating to watch, that our intimate involvement in watching his slow disintegration is akin to the sorrow and frustration felt by those closest to him–Ada, Esther, and his guardian, Mr. Jarndyce. Because most of his “dark” journey is so closely related by Esther, we can’t help but feel as though we are WITH these three characters, watching this poor young man practically disappear before our eyes. Maybe the Krook metaphor applies to him, also?

But my gosh, there are other characters in this novel who have or who will likewise succumb to this kind of obsessive-charged dissolution. Miss Flite comes to mind, certainly Mrs.Jellyby and also Mrs.Pardiggle. In their individual narratives–most of which have taken place before the beginning of BLEAK HOUSE, they will have slid or are presently sliding down the slippery slope toward a single-minded deterioration. The most violent end of this “process” comes of course with the “spontaneous combustion” of Krook–where the idea is that he is completely destroyed by his senseless accumulation of rags, bones, and paperwork, much of which is drawn from Jarndyce vs Jarndyce. His demise, I believe is the mark of what all these self-destructive tendencies and obsessions lead to. The fact that he can’t read, and that his accumulation of all this stuff is so totally non-productive, makes of him a central symbol in this novel!

And you mention Steerforth in COPPERFIELD as being among those who “steer” themselves into these same troubled waters (yes I think the storm that engulfs him IS the central symbol of DC), as he, alone, is responsible for his own self-destructive behavior which, as with all the other errant and obsessives, wreck havoc with all who get in their way–either physically or psychologically. But I also think that our dear David tends to move down this same slippery slope, as we see him constantly making wrong moves, especially in his love life and the other relations he forms and decisions he makes. He persistently moves into the dark, out of the dark, into the dark and, finally, out of the dark–and sometimes we readers are, for sure, in the same despair over the choices he makes–as we are with Richard. There is that same want of awareness in David that we see in these self destructive characters in BH–those who in spite of all advice and appearances to the contrary, avoid rationality and allow themselves to take the self-destructive plunge. Fortunately David, with the help of Agnes, “finds himself,” and probably comes out of his novel with an intact personality.

But I also think of the slow but inevitable movement that Mr.Pickwick makes toward prison in HIS novel, and his very stubbornness that steers him in that direction, and then there’s Alfred Jingle and his companion and we find them in the same situation. WE “love” Pickwick and hate to see that he has allowed himself to go “down THIS dark path,” and hope that reason will take over and that he will remove himself from this dire circumstance. And of course he does with the help of his lawyer and the heroics of Sam Weller. But he, like David, finds himself on the precipice, in the midst of a darkness–that could easily swallow him up and make him a sort of “Krook”–“spontaneously combusting” while languishing behind the walls of his prison….

Naturally, then, there are MANY characters in the novels we have read who also go down this slippery slope toward darkness, some WE (as readers) love, some who are much beloved by others in their novels, But this, at least, is a start toward recognizing how all-encompassing this idea works which you, Stationmaster, have so meaningfully and beautifully put together!

LikeLiked by 3 people

It’s likely that Dickens meant for Krook’s spontaneous combustion to be a metaphor for what happens to Chancery’s victims. But my mental image of Richard, Miss Flite and Gridley is of them withering and crumpling up rather than exploding.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There’s something I noticed on this read that confuses me. Ada reminds Richard that Jarndyce and Jarndyce “had its share in making us both orphans we were very young.” I don’t remember how it did that. Did the Clares and the Carstones commit suicide like Tom Jarndyce? That seems oddly specific even for Jarndyce and Jarndyce. Or is it more like they devoted all their time, money and energy to reaching a settlement that they should have devoted to earning money and so starved to death? In that case, how did little Richard and Ada survive themselves?

In Chapter 40, the third person narrator actually refers to himself. (“…so did they see this gallery hushed and quiet, as I see it now; so think, as I think, of the gap that they would make in this domain when they were gone; so find it, as I find it, difficult to believe that it could be without them; so pass from my world, as I pass from theirs…”) It was fairly normal for Dickens to refer to himself in his prose in some other books, most memorably in A Christmas Carol, but he didn’t do it as the third person narrator of Bleak House, leaving all that to Esther. Her narration arguably starts to “slip” too. In Chapter 45, she describes Vholes with undisguised loathing, not attempting to be gracious or merciful at all. (“…the one so open and the other so close, the one so broad and upright and the other so narrow and stooping, the one giving out what he had to say in such a rich ringing voice and the other keeping it in in such a cold-blooded, gasping, fish-like manner…”)

I love the glimpse Dickens gives us of Skimpole’s family in Chapter 43 and I love how he tries to explain how Skimpole got the way he was. Of course, it’s Jarndyce giving the explanation and he has an overly generous view of Skimpole so his psychological explanation may need to be taken with a grain of salt.

Speaking of how characters got to be the way they are, could this description of Tulkinghorn imply that he started out much more innocent and had to evolve over time into the creepy character we know and hate?

“Like a dingy London bird among the birds at roost in these pleasant fields, where the sheep are all made into parchment, the goats into wigs, and the pasture into chaff, the lawyer, smoke-dried and faded, dwelling among mankind but not consorting with them, aged without experience of genial youth, and so long used to make his cramped nest in holes and corners of human nature that he has forgotten its broader and better range, comes sauntering home. In the oven made by the hot pavements and hot buildings, he has baked himself dryer than usual; and he has in his thirsty mind his mellowed port-wine half a century old.”

It’s interesting (to me) that Sir Leicester is more pleased to hear that Skimpole is an amateur artist than he would be to hear he were a professional one. Was being a professional artist a way lower class people could gain power? We know Sir Leicester would hate that. Or his pleasure just because Skimpole being an amateur means he won’t criticize the paintings at Chesney Wold?

Dickens does a great job conveying that Esther really doesn’t want to marry Jarndyce while having her scrupulously avoid saying so in her prose. He also does a great job implying that Jarndyce himself is as grossed out by the idea as he is enamored of it.

Esther losing her temper at Richard when he assumes Jarndyce is manipulating Ada and using her as a bribe is memorable in that it’s the only time in the book that she admits to exploding with anger.

This never occurred to me before but it’s kind of odd that Jenny and Woodcourt are simultaneously mad at Jo for running away from Esther and mad at him giving her the smallpox. If he’d run away earlier, maybe she wouldn’t have gotten them, and neither would Charley. But I understand that they’re probably not thinking with perfect clarity when it comes to the subject of Esther and her misfortune.

Actually, something else just occurred to me as I was writing this comment. How come Charley’s face wasn’t disfigured by smallpox? I understand from a narrative standpoint, Esther is the main character and Charley isn’t and there’s enough drama in the book without both the heroine and her sidekick getting their faces disfigured by smallpox. But, realistically speaking, shouldn’t Charley’s face also be ravaged?

Let’s talk about this quote. (Well, actually, I just want to talk about this quote. Nobody else needs to do so.)

“Jo is brought in. He is not one of Mrs. Pardiggle’s Tockahoopo Indians; he is not one of Mrs. Jellyby’s lambs, being wholly unconnected with Borrioboola-Gha; he is not softened by distance and unfamiliarity; he is not a genuine foreign-grown savage; he is the ordinary home-made article. Dirty, ugly, disagreeable to all the senses, in body a common creature of the common streets, only in soul a heathen. Homely filth begrimes him, homely parasites devour him, homely sores are in him, homely rags are on him; native ignorance, the growth of English soil and climate, sinks his immortal nature lower than the beasts that perish. Stand forth, Jo, in uncompromising colours! From the sole of thy foot to the crown of thy head, there is nothing interesting about thee.”

There’s a good argument to be made that Dickens was being hypocritical here. In Chapter 30, he criticized the Jellybys’ wedding guests for each obsessing over their personal “Missions” in life while dismissing each other’s. Here he dismisses Mrs. Jellyby and Mrs. Pardiggle’s missions while implying that everyone should focus on his personal mission, the poor and uneducated of England. That’s a legitimate criticism of Dickens/Bleak House but I think Dickens’s critique has some validity too. There probably is a temptation to focus on saving the poor of other countries, especially really distant ones, since there seems to be more glamour and glory in that. Seen up close, people like Jo aren’t glamorous at all but they definitely need help and there’s something to be said for England focusing on Ignorance and Want in its own people before trying to rescue the rest of the world. I know that’s pretty much what I already wrote in my article about “the Anti-Dickensian Dickens Book” but I really do find it interesting.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Stationmaster, I don’t think the narrator is speaking of himself in the passage you mentioned as it is prefixed with ‘a Dedlock in possession might have ruminated…’ and the ‘I’ refers to that same ‘Dedlock in possession’ and details their thoughts (without helpful quotation marks)

The passage you quoted about Tulkinghorn contains the line, ‘dwelling among mankind but not consorting with them,’ which has strong echoes for me of this stanza from Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimmage:

I have not loved the world, nor the world me;

I have not flattered its rank breath, nor bowed

To its idolatries a patient knee,—

Nor coined my cheek to smiles, nor cried aloud

In worship of an echo; in the crowd

They could not deem me one of such; I stood

Among them, but not of them; in a shroud

Of thoughts which were not their thoughts, and still could,

Had I not filed my mind, which thus itself subdued.

much of the rest of the stanza could apply to Tulkinghorn too! perhaps this from Chapter 2:

He never converses when not professionally consulted. He is found sometimes, speechless but quite at home, at corners of dinner-tables in great country houses and near doors of drawing-rooms, concerning which the fashionable intelligence is eloquent, where everybody knows him and where half the Peerage stops to say “How do you do, Mr. Tulkinghorn?” He receives these salutations with gravity and buries them along with the rest of his knowledge.

In fact, I think Tulkinghorn is subject to many allusions throughout the novel which enhance the sense of his mystery or malevolence.

In that same section of Chapter 2, the description of his black dress One peculiarity of his black clothes and of his black stockings, be they silk or worsted, is that they never shine. Mute, close, irresponsive to any glancing light, his dress is like himself. – like Satan in Milton’s Paradise Lost (Book IV), ‘His lustre visibly impar’d’

Your passage above refers to him as ‘a dingy London bird’ elsewhere (C 10) he is almost likened to the crow that Mr Snagsby sees flying to Lincoln’s Inn Fields:

The day is closing in and the gas is lighted, but is not yet fully effective, for it is not quite dark. Mr. Snagsby standing at his shop-door looking up at the clouds sees a crow who is out late skim westward over the slice of sky belonging to Cook’s Court. The crow flies straight across Chancery Lane and Lincoln’s Inn Garden into Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

Here, in a large house, formerly a house of state, lives Mr. Tulkinghorn.

Before the quoted passage, Chapter 10 has contained numerous allusions (largely deepening a supernatural/paranormal and mysterious vibe) to both Hamlet (4) and Henry IV Part 2 (2)

There is a foreboding hanging over this chapter (which ends in the discovery of a death) and the above passage about the crow (for me at least) seems to colour our perception of Tulkinghorn with something dark and malign – recalling Macbeth’s speech:

Come, seeling night,

Scarf up the tender eye of pitiful day;

And with thy bloody and invisible hand

Cancel and tear to pieces that great bond

Which keeps me pale! Light thickens; and the crow

Makes wing to the rooky wood:

Good things of day begin to droop and drowse;

While night’s black agents to their preys do rouse.

-Macbeth III (ii)

With Tulkinghorn (The crow) being one of ‘night’s black agents’

The invocation of night (Similar to Lady Macbeth’s earlier ‘Come, thick night,…’ etc) is recalled at the end of the Nemo death episode by Chapter 11’s

Come night, come darkness, for you cannot come too soon or stay too long by such a place as this! Come, straggling lights into the windows of the ugly houses; and you who do iniquity therein, do it at least with this dread scene shut out! Come, flame of gas, burning so sullenly above the iron gate, on which the poisoned air deposits its witch-ointment slimy to the touch! It is well that you should call to every passerby, “Look here!”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Stationmaster: Dickens’ social criticism definitely seems more focused on society’s problems as they exist IN England and more specifically London. The far-flung “colonies” he seems much less interested in, as we see in his constant critical examination of Mrs. Jellyby and her charitable obsessions. Because he treats her so comically and so harshly, I begin to wonder about his thoughts regarding British colonization projects world wide. It would seem that he is more anti-colonization than pro-colonization, with his intense focus on and critique of the ills of society at home. In his eyes, he might see the British interests abroad as a willful misuse of time, money and people. But ultimately I don’t know, although I think that recent evaluation of his work over the past 40 years would reveal a number of writers who deal specifically with his attitudes toward colonization.

The various British colonial “projects” really involve exploitation and subjugation–all leading to British hegemony and financial gain. Hence, he MIGHT see that the British goals of using other countries for financial gain would simply parallel and perpetuate the evils that exist in his mother country. If this notion is true, then the “Jellybys” (and their ilk) of BLEAK HOUSE (and therefore London) would seem to be emblems and symbols of misguided colonial policies and the ways in which the would-be philanthropists of England can get obsessively caught up in this system….

LikeLiked by 2 people

Once we know all about Esther’s aunt/godmother, she becomes in retrospect one of the most complex characters in the book. On the one hand, she was actually noble in giving up a presumably happy marriage to shield her sister, her sister whom she didn’t even like, from the consequences of her actions and raise Esther as her own. Her new neighbors probably assumed Esther was her own illegitimate child, so she can be seen as kind of a Christ figure, taking on the punishment for someone else’s sin. On the other hand, she was inexcusably cruel to her sister, letting her believe that her child had died, and to Esther.

I kind of wonder how nobody figured that Esther was really Lady Dedlock’s child. I’m pretty sure women back then had to go “in confinement” for their pregnancies and since hers was embarrassing, we can assume her family would definitely want her far away for it. Wouldn’t it raise people’s suspicions if Honoria Barbary disappeared from society for ten months or so and then her sister suddenly has custody of a baby? Of course, the aunt did move far away from everyone she knew, and the Barbary family wouldn’t have been well known before Honoria married Sir Leicester Dedlock, so presumably the new neighbors wouldn’t have known about the confinement. I still wonder though how she hid Baby Esther from her mother and everyone else in the interim.

I’m sorry I keep poking holes in the plot this week. That just seems to be where my mind goes right now.

Remember what I wrote before about Dickens seemingly agreeing more with Mr. Rouncewell’s views on class than on Sir Leicester’s but not putting him on a pedestal? We see the best example of that in Chapter 48 in which he’s rather insensitive to Rosa’s distress, wanting her to “have a spirit” and defy the Dedlocks, though the book stresses that he doesn’t speak angrily to her and that he’d be friendlier if Lady Dedlock were not putting on a show of unfriendliness.

Shakespeare fans may note two allusions to Macbeth in Chapter 48. Sir Leicester’s debilitated cousin compares Lady Dedlock to that “inconvenient woman—who WILL getoutofbedandbawthstahlishment—Shakespeare.” And at the end of the chapter, Tulkinghorn’s bloodstain on the floor is described as “so easy to be covered, so hard to be got out.” This, of course, recalls the imaginary bloodstains Lady Macbeth couldn’t wash away. It reinforces the theme of guilty secrets and leaves us wondering if Lady Dedlock is the one who murdered Tulkinghorn.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m a big Shakespeare fan, and I love a good allusion too! And these that you mention are great examples and part of the many allusions to Macbeth which pervade Bleak House – where Fair may be foul and foul may be fair! And where at the very beginning of the journey in chapter 1 we literally ‘Hover through the fog and filthy air!’

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Everywhere and always, when human beings either cannot or dare not take their anger out on the thing that has caused it, they unconsciously search for substitutes, and more often than not they find them.”

― René Girard, The One by Whom Scandal Comes

Dear Fellow Inimitables,

Well, the King Inimitable has us all mired in mystery, and even muddled by the motivations of various characters!

As Rob compassionately observes, we are “entitled to feel a little overwhelmed by the mystery of it all.”

I feel the depth, breadth, and height of Dickens’ astonishing world-building, helping us all to reflect more deeply on the worlds (both inner and outer) that we inhabit.

You all have done an extraordinary job of exploring the “mystery of it all,” and I would like to offer one more thought/perspective: a tendency I might term “displacement”—so cogently portrayed by Dickens.

As I reflect on the pervasive theme of personal and collective responsibility for our individual and social lives that Dickens depicts, I see how deftly Dickens shows us the human capacity to displace our responsibility—to focus, even single-mindedly, on influences and realities beyond our control. It might be described as a kind of psychological “scapegoating”—assigning our aspirations, frustrations, and various energies to something outside of us that we cannot control. The “Chancery” of our lives.

It seems that the Jarndyce versus Jarndyce case and the convolutions of the Chancery are the central displacement in BH: If only the case would be resolved . . . .

How many characters in BH have hitched their star to this never-ending, consuming legal process—this consummate displacement?

We, any of us, can so easily become obsessively involved with something outside ourselves over which we have so little control—like the Chancery and its proceedings—expending precious time and energy that are never to be recovered.

John Jarndyce prophetically sounds the alarm and seeks to caution susceptible souls about the dangers of the case and preoccupation with it. Of displacement of our real lives.

Still, the “displacement” of our lives, assuming a substitute reality (“Chancery”), lurks for everyone.

The displacement can be wealth, fame, power, prestige. Whatever glitters.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. analyzed this “displacement” phenomenon so exquisitely in American life and politics.

“In international conflicts, the truth is hard to come by because most nations are deceived about themselves. Rationalizations and the incessant search for scapegoats are the psychological cataracts that blind us to our sins. But the day has passed for superficial patriotism. He who lives with untruth lives in spiritual slavery.”

Spiritual and psychological slavery, precipitated by displacement of one’s legitimate and proper concerns and taking up obsessively the concerns of a system or other outside force such as Chancery, seems to be a huge and pervasive theme in BH. And, in our own lives.

Thank you, King Inimitable, for this powerful cautionary tale!

Daniel

LikeLiked by 3 people

Echoing sentiments above, there is just so much going on in this novel that I find myself overwhelmed with (virtual) pages of notes and documents like Mrs Jellyby’s table, Mr Vhole’s blue bags, and Jarndyce and Jarndyce in general. So just a couple of notes here for now.

I remember reading somewhere, I think in reference to Jane Austen, that the best way to plan a novel is to create a set number of characters in a set number of locations and to have them interact with each other in a set number of ways. I think Dickens does in “Bleak House” to perfection. A lot of “Bleak House” relies on coincidence but this is expedient – it is expedient that Mrs Rachael should be Mrs Chadbrand, that Miss Barbary should be Lady Dedlock’s sister and Mr Boythorn’s ex-lover, that Jo should know Nemo, Jenny and Liz who should know Esther who should know Woodcourt who should come upon Jo and Jenny, who should have interacted with Lady Dedlock who should be Esther’s mother and Nemo’s lover, etc., etc., etc. I never cease to be amazed at how Dickens pulls it off. The coincidences seem so natural – perhaps a few are a little forced – but given the circle which these characters inhabit it seems natural that they would interact in the way they do.

We’ve talked a lot about responsibility and motivation in this novel and how there always seems to be a “yes, but” lingering around the discussion. So I want to talk about Miss Barbary, whose place in this story is full of coincidence, and about whom I can’t quite make up my mind.

When Esther described Miss Barbary in Ch 3 as a “good, good woman” I think what we are to understand from the repetition of the word “good” is not that she is an exceptional example of a nice or worthy woman but rather that she is an exceptional example of what a nice or worthy woman SHOULD be. That is, she is an accurate representation (i.e., facsimile or image) of a good woman but is not, in fact, one. But is there any wiggle room here? On one hand Miss Barbary is simply Esther’s unnecessarily evil godmother while on the other she almost absolves herself by (perhaps unconsciously) contriving to reunite Esther and her mother (hear me out).

The little we are told of her actions at the time of Esther’s birth are contradictory in terms of whether they reflect well or ill on her. Faced with the potential scandal of her unmarried sister’s pregnancy, she apparently takes care of that sister during her confinement and childbirth. And then in what could only be an effort to preserve that sister’s reputation she declares the baby dead, renounces her sister, and breaks all ties with her (Ch 29 & 36). The baby, however, is not dead and so, rather than disposing of it at a foundling hospital or workhouse, she breaks ties with her own lover, Mr Boythron (Ch 43), assumes a new identity (Ch 17) and secludes herself with a couple of servants and raises the child on her own (Ch 3 & 17). In the course of raising the child she writes anonymously to Mr Jarndyce and arranges for him to become the child’s guardian after her own death. So far pretty “good”. Yes, but . . .

This whole scenario is tainted by the meanness with which she rears the child. Her adherence to religious teachings, her self-denial, and her guardianship of Esther appear on the surface to be “good” but in reality her over the top Calvinistic religion, self-pity, general meanness, and unfeeling attitude toward poor little Esther are on a par with or worse than the Workhouse system toward Oliver, Mr Dombey’s dismissal of Florence, and the Murdstone’s war against David. Steeping Esther’s childhood in unexplained shame and guilt was an unnecessary persecution of an innocent for the shortcomings of herself and her sister. Yes, but . . .

The one really good thing Miss Barbary did was to write to Mr Jarndyce and to arrange for him to take over guardianship for Esther after her death. With every option of disposal or maintenance of the minor child available to her from a foundling hospital to a convent, that Miss Barbary should choose someone she already knows goes contrary to her assumed seclusion. We can assume she knows Mr Jarndyce via her relationship with Mr Boythorn, or perhaps she knows Mr Boythorn via Mr Jarndyce (Ch 18). Either way, she would have first hand knowledge of Mr Jarndyce as a kind and caring man. By placing Esther under his guardianship she must have known or at least though it likely that Esther might visit Mr Jarndyce and possibly might also visit Mr Boythorn in which case she might see and possible meet Lady Dedlock as a near neighbor of Mr Boythorn. So, in a way, it is by Miss Barbary’s contrivance that Esther and her mother are first separated and then reunited. Yes, lots of coincidences, but . . .

So Miss Barbary’s responsible act, motivated by both unselfish and selfish concerns, is administered irresponsibly (with the one exception of enlisting Mr Jarndyce) but produces a highly responsible adult (Esther), and leads to the discovery of her sister’s irresponsible act which, in its turn, set the whole thing in motion. Dare I say it, it’s all rather foggy!

LikeLiked by 4 people

Chris–your opening sentence of the 2nd paragraph is so beautifully and memorably stated. Here it is in all its glory:

“I remember reading somewhere, I think in reference to Jane Austen, that the best way to plan a novel is to create a set number of characters in a set number of locations and to have them interact with each other in a set number of ways. I think Dickens does [it?] in “Bleak House” to perfection.”

We spoke a lot last week about the crazy complexity of this novel, and hinted at the way things seem to be linked, in some way, one to another. But here you present that linkage in more defined and useful terms. In short, one person, one activity, one journey seems, somehow, to have a “mysterious” and more covertly revealed (“coincidental”) connection to other persons, activities, and journeys.

I’m wondering, then, if there are more or less other and many “connective tissues” which join all these characters and situations to one another. For example, does Guppy exist as more than an important character in this novel, to the extent that we could label him as perhaps a catalyst or “connector”–and thus see him as something (or someone) who represents, as you say, part of the intended “interacting” structure of the novel. As clerk for Kenge and Carboy he just keeps appearing in so many casual and then more crucial moments–some very lightweight (early moment with Esther Ada and Richard taking them to see Mrs. Jellyby), some more important (coming to Bleakhouse to meet with Boythorn and proposing to Esther), then, more importantly, meeting several times with Lady Dedlock in a more suggestive and aggressive capacity, and later, leading the novel and the reader to the famous and bizarre and climactic Krook spontaneous combustion sequence of events.

Thus: In and of himself, he is an interesting and dramatic character, but he also operates as something like a structural DEVICE. He comes on as a bit of a dandy, sees himself as more important than he is, but also shows himself aggressively to be a predator–seeking an advantageous marriage, money, status, leverage over the aristocracy and one who wants some of the by-product rewards of the Jarndyice case. But beyond all these personal attributes he is novelistically a narrative conduit.

And I’m wondering, then, if he is just one representative of others in the novel who fulfill this dual function?

And the next person who comes to mind in this respect is Esther. Of course, she is probably the most fully articulated personality in the novel, and she stands out as most likely the novel’s main character, but we might also see her as a DEVICE in much the same way as I’ve describe Guppy. Like him, she is constantly visiting other characters, other venues in the novel, working to connect her narrative to the various other parts of the narrative that are given us by the omniscient narrator. And finally, Her role as connector really climaxes in her relationship with inspector Bucket as they, together, later in the novel, go on the long journey to “detect” the whereabouts of Lady Dedlock.

Connections, connections, connections–throughout this momentous novel, many as you have stated are–or seem to be coincidental, but many are also developed by the movements and desires of some of the novel’s lesser or main characters. In closing, I’d say there is so much more to be considered regarding both of these “connecting instances.”

LikeLiked by 2 people

Lenny – I couldn’t agree with you more regarding Guppy. Indeed, as I think we’ve said about Dickens in particular before, no character is simply “there” – they are there for a reason, a purpose, they absolutely have a role to play. Your comments reminded me of my 1999 Applied Study Term thesis entitled, “The Role of Major-Minor Characters in Mary Barton, North and South, Hard Times, and Felix Holt: Agents of Reconciliation”. Here is the pertinent paragraph from my thesis for your consideration:

‘In his book “The Supporting Cast: A Study of Flat and Minor Characters”, David Galef tells us that minor characters “carry out much of the mechanics of the fiction” (1). Further, they “fit where no [major] character would” (2) and add “background” (11) and “depth” (22). Minor characters are “MADE minor by the author” for a specific purpose, either functional or illustrative (24) (emphasis in original). Galef identifies seven structural types (narrators/expositors, interrupters, symbols/allegories, enablers/agents of action, foils/contrasts, doubles/doppelgangers, and emphasizers) and five mimetic types (eccentrics, friends/enemies/acquaintances, family, people/chorus/background, and subhuman) of minor characters (16-21). The structural types perform “an active job in the unfolding of the narrative” by being either verbally or physically active in some way or by being representative of some thing or some characteristic of or opposed to another character (16). The mimetic types come “under the heading of verisimilitude,” that is, they represent what is real and familiar (16). “The analysis of minor figures will” says Galef, “inevitably reveal the painstaking construction of the work: how the author intends to get from alpha to omega, or what contrasts he has in mind, or what thematic principles he is stressing” (22).’

Galef’s book was and continues to be extremely helpful in my on-going study of minor or secondary characters. When we begin to look for what “role” a minor character is “made” to perform their place in a novel, indeed the novel itself, becomes richer. Dickens’s skill at “making” his secondary characters “perform” is just so brilliant!!

LikeLiked by 3 people

Wow, Chris, what a wonderful resource you have there! I can see how beautifully it would apply to Dickens’ novels generally and to BLEAK HOUSE in particular. In this context, then, your second paragraph is just a humdinger. It is and will be so useful to us as we consider the roles, etc., of the so-called minor characters in BH! Egads, such a relevant set of remarks. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Chris, this is absolutely fascinating!

I am hoping that the time will not run out before I can assemble an analysis of one of our minor characters in Bleak House who I think exemplifies a lot of this. The character is Guster. As well as being instrumental in the workings of the plot as it approaches its conclusion, her presence and presentation expands and deepens some of the background and themes. As well as providing a few comic moments along the way, she is doubled/connected to a few of the more major characters in key ways 😀

LikeLiked by 2 people

And then there’s Mr Tulkinghorn. His job as solicitor to great Families is “to be the silent depository” of “family confidences”, “the steward of the legal mysteries, the butler of the legal cellar, of the Dedlocks” in particular. (Ch 2) As “a great reservoir of confidences,” (Ch 10) his one job is to gather the secrets, confidences, the proverbial skeletons in the closet and, most importantly, to safeguard them from becoming known and/or doing damage to the Family and the Family name. So I’m wondering, then, why he threatens Lady Dedlock with telling her secret to Sir Leicester.

Granted, Sir Leicester is the head of the Dedlock Family and as such he has a right to know. But as Tulkinghorn himself says in Ch 41, knowledge of Lady Dedlock’s secret would shake Sir Leicester to his very core. Sir Leicester’s reaction, be it physical, mental, and/or emotional, would undoubtedly lead to gossip and quite likely a breach or break in the Dedlock marriage which “would spread the whole truth, and a hundred times the whole truth, far and wide. It would be impossible to save the family credit for a day.” So, the decision of whether it is better to tell Sir Leicester everything or tell him nothing is not an easy one to make and Tulkinghorn has much to consider. The secret must be “hushed up if it can” and thus Tulkinghorn and Lady Dedlock come to an understanding. She is to maintain her charade and to wait for Tulkinghorn to come to a decision as to how he/they should proceed and he will give Lady Dedlock fair warning before taking any action. However, her dismissal of her maid, Rosa, Tulkinghorn views as a direct violation of their agreement (Ch 48). He therefore declares the agreement null and void warning Lady Dedlock that she will receive no forewarning if and when he decides to disclose the secret to Sir Leicester, which he seems to suggest may be very soon.

But WHY tell Sir Leicester? For the reasons stated above by Tulkinghorn, telling Sir Leicester would result in great if not total damage to the Dedlock name and thus violate Tulkinghorn’s stated function of preserving it.

My guess is that Tulkinghorn is toying with Lady Dedlock – like a cat playing with a mouse before devouring it. He doesn’t like women – “There are women enough in the world . . . too many; they are at the bottom of all that goes wrong in it” (Ch 16) – or marriage – “most of the people I know would do far better to leave marriage alone. It is at the bottom of three fourths of their troubles” (Ch 41). But the more he watches Lady Dedlock “with the interest of attentive curiosity” (Ch 41), the more she becomes “a study” for him (Ch 48). Her “strength of character” fascinates and astonishes him causing him to repeatedly ruminate on “What power this woman has to keep these raging passions down!” (Ch 41 & 48). Perhaps I’m reading too much between the lines here but it seems rather like soft porn when Tulkinghorn confronts Lady Dedlock in her room. He sits: “taking a chair at a little distance from her and slowly rubbing his rusty legs up and down, up and down, up and down,” then “He stops in his rubbing and looks at her, with his hands on his knees” with “an indefinable freedom in his manner” and again “crossing his legs and nursing the uppermost knee”. (Ch 48) But I digress . . .

Being privy to her secret gives him power over her which he just can not help exploiting. I think Mr Gridley’s assessment of Tulkinghorn was right, “He is a slow-torturing kind of man.” (Ch 47) I think he has no intention of telling Sir Leicester but that he enjoys watching the effect of his threat on this woman of strength for reasons enumerated by our third person narrator:

“It may be that he pursues her doggedly and steadily, with no touch of compunction, remorse, or pity. It may be that her beauty and all the state and brilliancy surrounding her only gives him the greater zest for what he is set upon and makes him the more inflexible in it. Whether he be cold and cruel, whether immovable in what he has made his duty, whether absorbed in love of power, whether determined to have nothing hidden from him in ground where he has burrowed among secrets all his life, whether he in his heart despises the splendour of which he is a distant beam, whether he is always treasuring up slights and offences in the affability of his gorgeous clients—whether he be any of this, or all of this, it may be that my Lady had better have five thousand pairs of fashionable eyes upon her, in distrustful vigilance, than the two eyes of this rusty lawyer with his wisp of neckcloth and his dull black breeches tied with ribbons at the knees.” (Ch 29)

I think he threatens Lady Dedlock because he can, but I think he overplays his hand with this threat – reminding me here of Carker and Edith Dombey. Like Carker, Tulkinghorn does not realize the extent of this Lady’s willpower – Lady Dedlock will NOT wait for others to determine her fate. She had done so once in listening to her sister and will not do so again.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Yeah, Gridley’s assessment is right on. “Slow torturing” just about sums Tulkinghorn’s character and activities to the “T.” But I think it also stands for the ways in which the Jarndyce suit in Chancery affects so many characters in the novel, especially our dear Richard. He is literally being tortured to death–as is Lady Dedlock. Good Lord, even as I write this I think about how symbolic her name is–she’s locked into death by her predicament in the novel. Holy cow!

LikeLiked by 3 people

Lenny, your comment got me thinking about her name, too –

DEADLOCK as in a state of inaction or neutralization resulting from the opposition of equally powerful uncompromising persons or factions (dictionary.com) – as we see in the battles between Lady Dedlock vs Tulkinghorn, Honoria vs Miss Barbary, Lady Dedlock vs the secret.

AND maybe

A Dead bolt which is a type of lock morticed into a door that can only be opened by using a key or handle normally comprised of steel, bronze or brass, and they extend deeper into the door frame than latches or spring bolts. Thus Lady Dedlock’s secret can only be accessed – confirmed – by the key of her letters to Capt. Hawdon

LikeLiked by 2 people

Chris, please forgive me as I am very much in allusion mode, but I’d like to offer a Tulkinghorn perspective in relation to the passage you quoted from Chapter 29, or rather the end of the paragraph which precedes it and the few lines at the beginning of the paragraph you quoted.

contemplating some of Sir Leicester’s fine artefacts, we have the end of the catalogue:

“One stone terrace (cracked), one gondola in distance, one Venetian senator’s dress complete, richly embroidered white satin costume with profile portrait of Miss Jogg the model, one Scimitar superbly mounted in gold with jewelled handle, elaborate Moorish dress (very rare), and Othello.”

Mr. Tulkinghorn comes and goes pretty often, there being estate business to do, leases to be renewed, and so on. He sees my Lady pretty often, too; and he and she are as composed, and as indifferent, and take as little heed of one another, as ever. Yet it may be that my Lady fears this Mr. Tulkinghorn and that he knows it.

it then runs into the passage you quoted.

Placing Mr Tulkinghorn immediately after a mention of Othello effectively creates an unstated stage direction: (Enter Iago)

the other items in the list also relating somewhat to Othello

gondola – Venice (Othello is The Moor of Venice)

Venetian Senator(‘s dress) – Brabantio?

white satin – almost evocative in this context of Desdemona’s innocence from blame/spotlessness of character

Scimitar – Moorish weapon

Moorish Dress

the paragraph which you quoted could as well be an analysis of Iago’s motivations as those of Tulkinghorn.

This parallel to a great literary villain seems to hint that we will not fathom Tulkinghorns motives.

Indeed, even our omniscient narrator cannot penetrate Tulkinghorn’s mystery. Indeed the narrator cannot fully penetrate Lady Dedlock’s graceful veneer of stately boredom either.

Were this the only mention/reference/allusion/echo to (or of) Othello this might not be so strongly implied. But there are many more tucked away within the chapters and passages of Bleak House.

Carker is a good double/parallel too. In seeming to serve he really serves himself.

Both Carker and Tulkinghorn have the dramatic presence and personas of Shakespearean magnitude villains, so I shall give the final words of this comment to Iago…

Were I the Moor, I would not be Iago:

In following him, I follow but myself;

Heaven is my judge, not I for love and duty,

But seeming so, for my peculiar end:

For when my outward action doth demonstrate

The native act and figure of my heart

In compliment extern, ’tis not long after

But I will wear my heart upon my sleeve

For daws to peck at: I am not what I am.

— Othello – Act I Scene I

😀

P.S Thanks for humouring me through my ‘allusion phase!’

LikeLiked by 1 person

Since we’re talking about Lady Dedlock and Tulkinghorn, here’s a question. Did she know how he was going to react to her dismissing Rosa? I kind of like the idea of her knowing since it makes her doing it in front of him admirably gutsy. But I wouldn’t be surprised if she didn’t. After all, it’s unlikely there would be that much gossip as a result of it. The implication seems to be that he’s looking for any excuse to consider their “agreement” broken.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think at this point Lady Dedlock doesn’t care what happens to her or her secret or even the Dedlock name. She’s already made up her mind to leave – in Ch 41 – and dismissing Rosa, in Ch 48, is done simply to spare Rosa contamination by association. The effect of this on Tulkinghorn is really of no interest to Lady Dedlock – recall, HE comes to see HER in HER rooms after Rosa’s dismissal and asserts HIS authority which I think Lady Dedlock pretty much rejects. I think Lady Dedlock’s mind is made up as to what she will now do and it has no bearing on Tulkinghorn or anyone else.

LikeLiked by 2 people

That’s the vibe I get from this part too but (SPOILER ALERT!) in next week’s reading, Lady Dedlock is prompted to run away by the revelations of two visitors. Why would Dickens include that if she were going to run away anyway? (I’m not trying to start a big argument here. Just bouncing around ideas.)

LikeLiked by 2 people

I agree with both of you, here. He undoubtedly exhibits misogynist and sadistic behaviors toward Lady Dedlock. The major evil antagonist in the novel?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry I’m so late to the discussion–all of these comments are so marvelous…I am all at sea!

Guppy: I love the conversation about him above. In some ways, he’s not only the consummate “connector” (Lenny?), and the “our mutual friend” of a novel of the same name, upcoming, but Guppy is in some ways the ultimate DETECTIVE in a novel full of detectives–including the reader, as Boze mentioned in the intro. I’m a HUGE fan of Bucket, and think he ranks among the great literary detectives with Sgt Cuff, Poirot, & Co, but when I think of Guppy, I think of the word used for the contemporary Los Angeles fictional detective, Bosch: a “grinder”. He tediously and painstakingly cultivates relationships of convenience–to his inquiries–and delegates where he needs to (Jobling), finding the story of Esther’s parentage before she herself, or Tulkinghorn, or Jarndyce, or Lady Dedlock herself can do so. It’s pretty extraordinary…! So, three cheers for our curious-minded little-fish-in-a-big-pond, Guppy!