Wherein The Dickens Chronological Reading Club (#DickensClub) 2022-24 introduces Hard Times, our nineteenth read as a group.

By Boze

Hello, friends! “What kind of education should a parent give a child? How much is the ambition of the self-made man really worth?” Can the imagination survive in a world of relentless utility and profit?

But before we embark, a few quick links:

- Historical Context

- Thematic Considerations

- A Note on the Illustrations

- Reading Schedule

- Additional References

- General Mems for the #DickensClub

- A Look-Ahead to Weeks One and Two of Hard Times

- Works Cited

Historical Context

Hard Times emerged from a very public beef between Dickens and his long-time illustrator, George Cruikshank.

As Harry Stone tells the story in his seminal book, Dickens and the Invisible World, in July 1853, Dickens—having reached the exact midpoint of his career—was finishing the final installments of Bleak House. He had retreated to Boulogne for the summer, away from the confusion and demands of life in London. A thoroughly pleasant holiday:

“He had rented a charming villa on a wooded hillside. The grounds included beautiful terraced gardens dense with thousands of roses and lush with a myriad other flowers. From his perch high in the hills he could see the picturesque jumble of Boulogne spreading down the slopes before him. The walk to the post office was ten minutes; to the sea, fifteen.”

After wrapping up Bleak House, Dickens was looking forward to a good, long rest. But of course Dickens was incapable of resting, and before very long his repose was disrupted by infuriating news from back home.

He learned from the Examiner, a weekly periodical edited by John Forster, that Cruikshank—who had illustrated Sketches by Boz, The Mudfog Papers, and Oliver Twist—had turned his hand to writing fairy-tales. (Britain in this period was entering a golden age of children’s literature, when authors like George MacDonald, Lewis Carroll and Edith Nesbit wrote fairy-tales for children as well as adults. Dickens himself would pen the wonderfully subversive “Holiday Romance.”) Cruikshank, however—one can almost see Dickens’s nostrils flaring even as the subject is mentioned—Cruikshank had forgotten the essential purpose of fairy-tales. He had turned the classic tale “Hop-o’-My-Thumb” into a treatise on the dangers of alcohol. He had given the story a treacly moral, putting into the mouths of fantastical characters the sort of ham-fisted sermon that Carroll would parody so deftly in the Alice books.

And this Dickens simply couldn’t tolerate. For Dickens, any attempt to enlist fantasy literature in the service of propaganda, however noble, risked sterilizing its effectiveness as a vehicle for the imagination. He credited the wonderfully weird tales in the Arabian Nights and other books with nourishing his play and creativity during the most horrible years of his adolescence. Without them, he might never have escaped the poverty of his youth and become a famous writer of imaginative fiction. Well-intentioned though Cruikshank undoubtedly was, by removing the fundamental strangeness and irrationality of fairy-tales he was depriving the next generation of the very things that had saved Dickens’s life.

And this perhaps needs some elaboration. Those who don’t read a lot of traditional fairy-tales tend to have a hazy notion, absorbed from the Victorians and Walt Disney, of sentimental stories for children. In fact, these stories are typically strange, violent and amoral, operating according to a kind of dream logic. Early in the Arabian Nights, for example, a man wanders through a door in a wall where no door had been a moment before; he finds a woman cooking fish in a skillet, and, as he watches, the fish fly out of the pan and begin to sing. There’s no moral here, nor should there be. But the warped imagery stretches the boundary of what’s possible, and this is precisely what would have enchanted Dickens, who would likely have agreed with Rabbi Abraham Heschel that “the world will not perish for want of information, but for want of wonder.”

“More and more through the 1840s and the early 1850s,” Stone writes, “Dickens was coming to regard the fairy-tale and its correlatives—fantasy, enchantment, legends, signs, and correspondences, indeed all the thronging manifestations of the invisible world—as potent instruments and incarnations of imaginative truth. The fairy-tale was the most important of those incarnations. It transformed mysterious correspondences and veiled manifestations into ministering art. The fairy story was an emblem, at once rudimentary and pure, of what contemporary society needed and what it increasingly lacked … The lesson, Dickens felt, was clear. In an age when men were becoming machines, fairy stories must be cherished and must be allowed to do their beneficent work of nurturing man’s birthright of feeling and fancy.”

Dickens rose to the defense of the imagination in two ways. First, he published his celebrated essay, “Frauds on the Fairies,” in which he insisted that fantastical literature should be taken seriously as a genre, rather than being dismissed as frivolous or treated as a vehicle for faddish social issues (a battle that many authors are still fighting today). The famous opening words—“In a utilitarian age, of all other times, it is a matter of grave importance that fairy-tales should be respected… A nation without fancy, without some romance, never did, never can, never will, hold a great place under the sun”—would prove hugely influential on the great fantasy authors of the following century. J. R. R. Tolkien’s lecture “Beowulf and His Critics” is an elaboration of Dickens’s theme, and Ray Bradbury would make a career out of defending the imagination in the same spirit, and with the same vociferous energy, that Dickens employs here.

Not satisfied with having written an essay, however, Dickens resolved to hammer home his thesis through narrative. He would write a book. And the book would be called Hard Times.

Thematic Considerations

“Now, what I want is, Facts. Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else, and root out everything else. You can only form the minds of reasoning animals upon Facts: nothing else will ever be of any service to them.”

Strikes and the Working Class

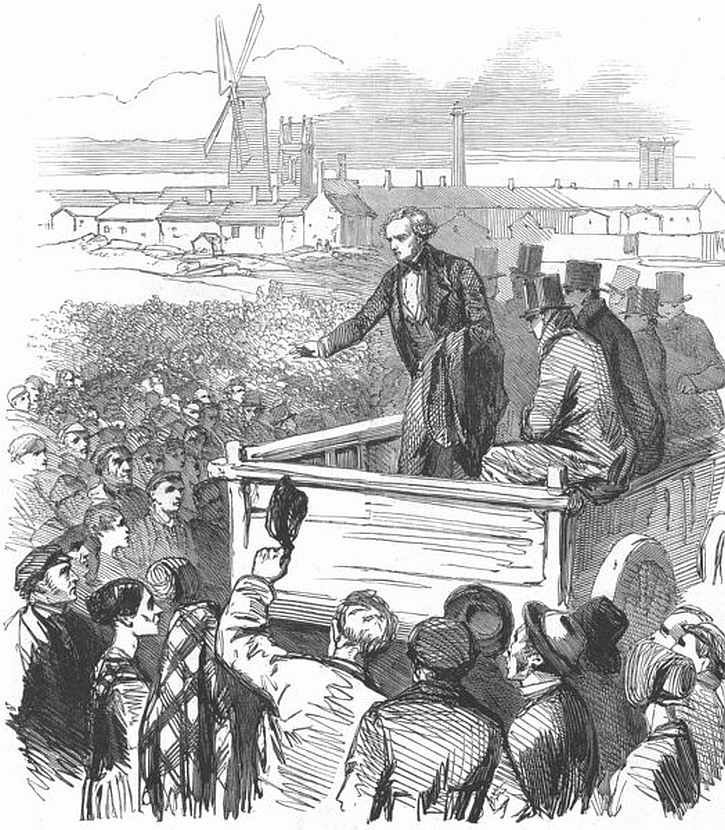

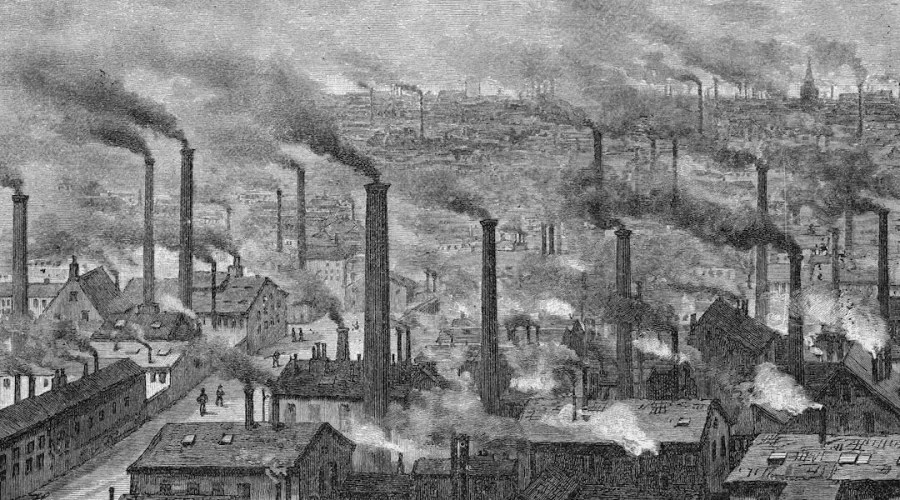

Another motivating factor in writing the novel was Dickens’s experience of a labor strike he had witnessed in the northern English town of Preston in January 1854, an experience that he recounted in the essay “On Strike” for Household Words. The laborers of Preston brought manufacture to a halt for seven months because the owners of the cotton mills had (ostensibly as a temporary measure) reduced their wages by ten percent in 1847 and had kept them at the same reduced rate at ever since.

Dickens was sympathetic to the cause of the workers, though he disapproved of strikes on principle, feeling that they were borne out of ignorance. In the case of Preston he sought to be a mediating influence, forging a rapprochement between the capitalists and the laborers. (It’s useful to remember that for all we talk of Dickens being the great champion of the poor, he wasn’t opposed to the engines of economy that had brought him success–though, in practice, one might argue, neither were Marx and Engels. Dickens didn’t seek a fundamental restructuring of society but a world in which those with means, guided by the ethics of the New Testament, bestowed private philanthropy on those without.)

Dickens did worry, however—as would many after him—that the laboring conditions of the working classes were depriving them of exposure to education, imagination and literature. The enrichment that literature provided was, for him, no less important than the giving of daily bread. In a speech given in 1857, to great applause, Dickens said, “In these times, when we have torn so many leaves out of our dear old nursery books, I hold it to be more than ever essential to the character of a great people, that the imagination, with all its innumerable graces and charities, should be tenderly nourished.” The knowledge that millions of the lower classes couldn’t read, and lacked even the most rudimentary education, was a source of constant vexation—recall his horror at the real-life cross-examination of the crossing-sweep George Ruby, who said under oath he had never heard of God or the Bible. This mission to elevate the minds of the working classes would become a more and more pressing concern in his later books.

A Note on the Illustrations

Hard Times is the first Dickens novel not to have been accompanied with illustrations—perhaps unsurprisingly, given the demands of trying to fit the story Dickens was telling within the five pages allotted by Household Words. As Peter Ackroyd writes:

He set to work in the third week of January 1854. He took out a sheet of his characteristic light blue writing paper, and calculated the amount he would need to fill five pages of Household Words each week. He was no longer used to writing in the weekly format and so, to expedite matters, he actually decided to arrange the new novel in monthly parts which he would then subdivide into the necessary weekly portions.”

In a letter to Forster, Dickens described the demands of “compression and close condensation” as “CRUSHING.” (Unusually for Dickens, the first page of the manuscript draft is covered in deletions as he struggled to find his footing.) The constraints of the new format were so taxing that his doctor recommended a week’s holiday midway through writing. When the serialized installments were finally published, they were split into two columns on each page, which gave the story the air of a journalistic piece and may have contributed to its appeal. Indeed, Hard Times was instrumental in reviving the flagging fortunes of Household Words. By the end of its run, circulation of the magazine had doubled.

Reading Schedule*

*Note: We will read Hard Times over the course of 6 weeks (followed by a 2-week break), with a summary and discussion wrap-up every other week. The book is divided into 3 parts, so we will use that as our division, even though Part Three is shorter than the other two.

| Week/Dates | Chapters | Notes |

| Weeks 1 & 2: 29 Aug to 11 Sept, 2023 | Book the First: Sowing. Chapters 1-16 | |

| Weeks 3 & 4: 12-25 Sept, 2023 | Book the Second: Reaping. Chapters 1-12. | |

| Weeks 5 & 6: 26 Sept to 9 Oct, 2023 | Book the Third: Garnering. Chs 1-9 |

Additional References

A few adaptations are available for those interested, including a well-reviewed miniseries from 1994.

And for the audiophiles among us, your co-hosts love Anton Lesser’s reading. And Rach is currently listening to our member Rob Goll’s marvelous narration!

General Mems for the #DickensClub

If you’re counting, today is Day 603 (and week 87) in our #DickensClub! This week and next, we’ll be beginning Hard Times, our nineteenth read of the group. Please feel free to comment below this post for the first and second week’s chapters, or use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter.

No matter where you’re at in the reading process, a huge “thank you” for reading along with us. Heartfelt thanks to our dear Dickens Fellowship, The Dickens Society, and the Charles Dickens Letters Project for retweets, and to all those liking, sharing, and encouraging our Club, including Gina Dalfonzo, Dr. Christian Lehmann and Dr. Pete Orford. Huge “thank you” also to The Circumlocution Office (on twitter also!) for providing such a marvellous online resource for us.And for any more recent members or for those who might be interested in joining: the revised two-and-a-half year reading schedule can be found here. If you’ve been reading along with us but aren’t yet on the Member List, we would love to add you! Please feel free to message Rach here on the site, or on twitter.

And for any more recent members or for those who might be interested in joining: the revised two-and-a-half year reading schedule can be found here. If you’ve been reading along with us but aren’t yet on the Member List, we would love to add you! Please feel free to message Rach here on the site, or on twitter.

A Look-Ahead to Weeks One and Two of Hard Times (29 Aug-11 Sept, 2023)

This week and next, we’ll be reading the first “book” of Hard Times, which comprises sixteen chapters. These chapters were originally published weekly, from 1 April to 20 May, 1854.

Feel free to comment below for your thoughts this week and next, or use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter.

If you’d like to read it online, you can find it at a number of sites such The Circumlocution Office; you can download it from sites such as Gutenberg.

Works Cited

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens. New York: HarperCollins, 1990.

Butterworth, R.D. “Dickens the Novelist: The Preston Strike and ‘Hard Times’,” Dickensian; Summer 1992; 88, 427; Periodicals Archive Online pg. 91

Douglas-Fairhurst, Robert. The Turning Point: 1851—A Year That Changed Charles Dickens and the World.

Simpson, Margaret. The Companion to “Hard Times.” Westport: Greenwood Press, 1997.

Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2009.

Tomalin, Claire. Charles Dickens: A Life. New York: Penguin Press, 2011.

This is going to seem totally out of left field but I’m going to share this lengthy quote from Welcome Lizard Motel, a memoir by Barbara Feinberg. It was written largely as a response to trends she noticed in award winning children’s literature (what she calls “problem novels”) that disturbed her, and it weirdly relates very well to Hard Times. I hope quoting all this doesn’t violate copyright. I’m going to be leaving out quite a bit from this passage and the whole thing is worth seeking out and reading BTW.

While the books are most often told by a child narrator, or narrator identified with a child, and in some the child’s language might sound more or less believable, many of the books rarely deliver what I consider an authentic child’s perspective. Something feels false. Something essential feels missing.

What is it? The answer is this. No child I have known experiences “reality” only in terms of what happens- “the facts.” For all children, except in cases of extreme pathology, there is a corresponding magical, imaginative counterpart to experience. This dimension does not have to be fully conscious, but exists nevertheless. By “magic” I do not mean only manifest magic as in a child’s belief or wish that he could turn invisible or fly. In fact, as children get older such manifest magic is understood increasingly to be the exclusive province of dramatic art and play, distinct from reality. But latent magic continues to abound in the everyday. There is chatter among the trees. The world vibrates with connections and within these connections, the world is more dangerous (than for adults) since the world can be alive and menacing but the world is more providential also since allies can be found in rocks, in the hopeful sunlight and the like. Within this universe, the child is the nexus but while he might be hindered or aided by the natural world, he is never alone. The point is that in childhood and well into early adolescence and in all poetic worlds the universe is animate or at least potentially animate with an unseen presence.

And it is precisely this dimension to childhood experience that is absent from many realistic novels and virtually all problem novels. No magic, manifest or latent, vibrates within them. Instead, in all of these self-proclaimed “realistic” stories, “reality” is understood as the opposite of imagination and fantasy, as if childhood were a dream from which children must be awakened-when in fact reality is not divisible from imagining for children. But in these books, children’s imagination is regarded as something that must be tamed, monitored, barred. The child protagonist, while presented with the darkest and most upsetting situations imaginable, is denied what in real childhood would exist in abundance: recourse to fantasy.

In problem novels, the worse the reality is, the weaker the character’s imagination and the more he must learn to cope just by relying on himself. In reality, I think the reverse is more often true: the harsher and more stressful life is for the child, the more fecund the imagination, as if the imagination is the natural antidote, sanctuary, resting place, insulation, place for renewal. In fact, deprivation and struggle can be the inspiration to create a fictional world. I know that in my own childhood, the more alone or upset I felt, the more the universe “spoke” to me…

Children also do not play in problem novels. Or if they do, the play sequences are never woven seamlessly into life the way, for example, Huck in Huckleberry Finn describes his playing life. (Huck, even though he has a whole array of family troubles, like the children in problem novels, is the very antithesis of a problem novel character.) Huck’s narrative moves in and out of descriptions of play and fantasy episodes. When he pretends to plot crimes with Tom Sawyer and a gang of other boys, deep in damp caves in the middle of the night, pages are devoted to descriptions of the oath pledged among the boys, involving exchanges of blood and promises of murder if the secret of their gang is revealed by any…In other words, the story told through Huck’s eyes portrays play the way it really feels to children: deliciously real yet at the same time not exactly the same as reality. Play and fantasy are facets of the prism through which life is experienced.

Many of the novels I’ve read seem not to regard play in this way. Any play sequences are described in a highly guarded, self-conscious way and are put in the story to teach a lesson. The “secret world” in Bridge to Terabithia is a perfect example of how fantasy is regarded in these books. The very bridge in question causes the death of a child. (Fantasy is dangerous.) And Jess’s realization at the end of the book-indeed the book’s epiphany, as it were-is that to grow up he must give up imaginary wanderings in favor of “reality…”

But while the children in problem novels don’t have rich imaginations, they are given mood states: they are depressed, nervous, worried. And they often feel very guilty. One child I know remarked, “In those books the kids always hate themselves.” Many characters are portrayed as feeling that they are the cause of the terrible things that occur.

This feeling of being the center of the universe-the cause of everything-is authentic enough to childhood, but where this omnipotence reigns in child thinking, doesn’t a whole world of other fantasies-comforting, deep ones-exist alongside it? Why deprive the child narrators of the rest of the experience?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Wonderful introduction, Boze—I LOVE the emphasis placed on the imagination, and on the debate with Cruikshank and his use of fairy tales as a tool, rather than an end in itself.

Just a few opening thoughts as I reread it again, this time via Rob’s marvelous audiobook. Mine are now more sparks of ideas rather than a coherent whole.

Interesting that the first chapter is entitled, “The One Thing Needful.” Of course, this is an allusion to the Martha and Mary story in the Gospels. The sisters are showing hospitality to Jesus in their home, and Martha is doing the busywork while Mary is sitting at his feet, just listening to him talk. When Martha complains that Mary isn’t helping her out, Jesus says, “Martha, Martha, you are worried and distracted by many things, but few things are needed—indeed only one. Mary has chosen the better part, which will not be taken away from her” (Luke 10:41-42).

We then move into Gradgrind’s classroom, and the first line is: “Now, what I want is, Facts.”

“NOW” + “FACTS”

There is no room for daydreaming, for brooding over the *past* or dreaming of the *future*, for considering the essence of things. We’re all practicality here, all Fact. We’re all Martha around here. (Don’t get me wrong—I love Martha, and she gets a bad rap, but in terms of a type of thought, an analogy, this is such a great shorthand for the hard and fast choice, the dichotomy, of what Dickens is setting up here.)

There’s no room for shades, tints, colors in this world—all starkness. Could we say that Martha and Mary here in Chapter 2 are Bitzer and Sissy, in their views of the world—i.e. in the definition of a horse? There’s no “natural tinge” of color in Bitzer; he looks “as though, if he were cut, he would bleed white.” But Sissy “was so dark-eyed and dark-haired, that she seemed to receive a deeper and more lustrous colour from the sun, when it shone upon her”—whereas the color “draws out” of Bitzer “what little colour he ever possessed.”

Of course, I suppose it goes without saying, although it is always helpful to reiterate it and to see the many ways in which it is repeated, but we have a dichotomy between childlikeness and the quenching/choking of the child, and of the childlike spirit, including in the names: M’Choakumchild, Childers, Kidderminster, etc.

It is interesting that we see some spark of hunger for imagination and wonder in Louisa and Tom early on, and the fact that Louisa is a fire-gazer (in her argument with Mrs Gradgrind), speaks well of her potential for imagination, fancy, thoughtfulness. But is she going to allow her upbringing, her education in nothing but Fact and Utility, squelch it all?

LikeLiked by 3 people

Yes, yes, yes… I heartily agree a wonderful introduction. (AS ALWAYS! I must hasten to add!)

Rach! I am so glad you have chosen to listen along with my audiobook version 😀 The same goes for those others of you who are giving my reading the once over. I am listening to me too, mainly because I have a copy close to hand, but also because I particularly enjoyed creating the audiobook too! I believe it was the first of my *Lockdown* recordings (of which there were quite a few – I am grateful that I seemed to acquire lots of extra time to do what I love. If there had been no covid lockdown, I believe that I never would have tackled an audiobook recording of Nicholas Nickleby.. I just wouldn’t have felt I had the time) I would always have done Hard Times, it being of a convenient and compact length.

Looking back to April 2020 when I first started the project, I begin to think that I arrived at Hard Times from the wrong direction… a little explanation of what I mean might be helpful at this point:

The order in which I produced my earlier Dickens audiobooks is as follows:

First was Oliver Twist back in 2017. This remains to date by far my best selling audiobook. It is also the one which seems to dictate the way in which I approach *narrating Dickens* (<–hopefully I will be able to explain this further in the coming weeks/books, but for now I'll leave it there as a tantalizing morsel of fact!)

My audiobook of A Christmas Carol (v1 on Audible) was actually my second recording of it. My first version I regard as an early practice version – it was also recorded at an audio standard lower than that required for current audiobook standards (all part of the learning curve!)

Next was A Tale of Two Cities in 2018 followed by Great Expectations in 2019

Following that, still in 2019, I started the narration for the multi cast version of David Copperfield with The Online Stage (In which I voiced David (young and old) and Daniel Peggotty plus a few smaller roles) – This project was one which I was also producing, checking and editing together – all of which was still ongoing at the time of my starting Hard Times.

This was the extent of my Dickens in audio format experience, and except for the addition of Nicholas Nickleby – these were, at that time, the only works I had read.

I loved Hard Times when I first read and recorded it!

Coming back to it now after having read those works which precede it, I find I love it all the more!

Oops, I'm waffling on again – I didn't mean to say so much right now – but I do hope to look at the ways in which my approach was at the time, and how it might differ now! For now I shall 'sow' the seed – perhaps next fortnight I will get onto some reaping!!

For now, other points which I wanted to make in response:

Love the allusions into the Bible story, Rach! There's a few good biblical names in HT: Josiah, Thomas, Rachel, Stephen. Also the titles of the three books, Sowing, Reaping and Garnering I am sure allude to some well known passages.

Never noticed the Child/Kid connection with EWB and Kidderminster first time around – more aware now that Dickens was clever with those names he chose 😀

By the same token with the onomastics – the names which indicate hardness, or being trapped/fixed/worn down/drowning?:

BOUNDerby, GradGRIND, STONE Lodge, BLACK-POOL, HartHOUSE (almost Hard House) PEGler

I'm sure there must be something in Slackbridge too, but he is next weeks fare!

Girl Number 20 for all this is named after the patron saint of Music and the French word for 'skirt'

Takes all sorts I suppose 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Also, friends, in case you’re interested, I tried to edit down the notes that Boze and I took on HT, so as not to repeat too much of what Boze incorporated into the intro, but for those who want some more of those Gradgrindian facts, hehe, here’s a link to the file:

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1Z7XjWhV6qVy6NzWp4rJpF5Bhthy89yuB/edit?usp=sharing&ouid=109063301212590134437&rtpof=true&sd=true

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for these extra notes, Rach and Boze… they’re great and fascinating and appreciated 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Boze, you have written poignantly and eloquently in this introduction, helping us immensely to enter into this work, “Hard Times,” with more awareness and understanding.

Rach and Boze, thanks much for culling various perspectives from the sources you draw on. Those are additional resources to equip us on the journey of experiencing “Hard Times” more fully.

I am early in experiencing Rob Goll’s wonderful rendering of “Hard Times” on Audible. I have a few thoughts to share.

1. Wonder and radical amazement: Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel is a most captivating rabbi, theologian, social activist, and thought leader of the twentieth century. Besides the fine quote that Boze cites (“the world will not perish for want of information, but for want of wonder”), there is the story of Heschel asking God (like Solomon asking for wisdom) for one thing: radical amazement. This gift of seeing things afresh, as miraculous, accompanied Heschel throughout his adult life.

2. Like driving nails into a coffin: Listening to Rob Golls’ captivating read of “Hard Times,” I am struck by the driving repetitive sound of FACTS, bringing to mind the image of driving nails into a coffin. This, of course, connotes a kind of spiritual and imaginative death.

3. “Not by bread alone”: * He said in reply, “It is written: ‘One does not live by bread alone, but by every word that comes forth from the mouth of God.’” (Matthew 4:4)

It is interesting that this conversation takes place between the Tempter and Jesus during Jesus’ forty days in the desert, as he prepared for his public ministry.

The Devil appeals to Jesus’ physical, earth-bound hunger; Jesus alludes to another “bread”—a spiritual one, fulfilling the Father’s will. The reality-based Evil One cannot conceive of a different “bread.” He lacks imagination.

4. The demands of “compression and close condensation”: The form—the “mold,” if you will—that Dickens had to pour his irrepressible imaginative life into seems to have constrained him.

I’m wondering about the sense of this work as more allegorical than narrative—more of a parable (perhaps a fairy tale?) than a novel.

It may be a combination of the constraining way in which he had to compose and release the installments and his intention of (perhaps) presenting a modern fairy tale about the evil of relying on so-called facts alone–lacking imagination, fancy, enchantment—to navigate the seen and unseen dimensions of our mysterious world.

Thanks again, Boze and Rachel, for your expert staging.

And thanks to you, Stationmaster, for your references to and citations from “Welcome Lizard Motel,” a memoir by Barbara Feinberg, which parallel and enrich our reading of “Hard Times” wonderfully.

Blessings, All,

Daniel

LikeLiked by 2 people

Does anyone know why Dickens didn’t just have Chapters 1 and 2 be one chapter? I’ve never understood that.

It’s no secret that Charles Dickens created a lot of characters, like Mr. Bumble from Oliver Twist and Reverend Chadband from Bleak House, who represent mindsets he despised. Thomas Gradgrind Sr. is fairly unique among them in that (skip to the next paragraph if you wish to avoid spoilers) he is redeemed in the end. The only similar “strawmen” characters in Dickens of whom that can be said are Scrooge and Tackleton from the Christmas books. And even before his third act redemption, Gradgrind can be pretty likeable, especially compared to Bounderby. While it’s debatable how it would be for Sissy Jupe to have to leave the friends she’s known all her life to go live/work at Stone Lodge and be brainwashed to only care about facts, Gradgrind clearly means it as an act of kindness and, putting his educational philosophy, it really is one. Unlike Dr. Strong from David Copperfield or Wackford Squeers from Nicholas Nickleby, Gradgrind genuinely wants to help his students. (In this way, he’s like Dr. Blimber from Dombey and Son but much more developed.) He doesn’t adopt his philosophy for self-serving reasons as Mr. Bumble does his.

My take on Gradgrind is similar to Chris’s take on Paul Dombey Sr. in that he’s one of my favorite Dickens characters but I wish he had some kind of backstory to give him greater depth. (I’d argue he needs this more than Dombey since his worldview is more outlandish and caricatured.) Why did he become so ardent about this crazy fact obsessed philosophy? Were his parents crushed by a giant book of poetry or something? Actually, it might be that Gradgrind was taught his philosophy by his parents. When discussing Louisa’s marriage with her, he says, ” I have stated it, as the case of your mother and myself was stated in its time.”

A character in Hard Times who represents views Dickens hated and who isn’t sympathetic in any way is Bounderby. While I think Dickens has basically sound satirical points to make with this figure, mainly how he stereotypes his discontented employees as wanting “to be set up in a coach and six, and to be fed on turtle soup and venison, with a gold spoon” and never listens to their actual complaints, I don’t enjoy hating him as much I do, say, Mr. Bumble. It’s hard to say why. There are people out there who generally find it annoying when storytellers demonize characters who hold views that they (the storytellers) believe to be wrong. I don’t have a consistent stand on this myself. Sometimes I find it annoying. Sometimes I don’t. Usually, I enjoy it when Dickens does it but not so much with Bounderby. It’s not that I’m annoyed with how Dickens manipulates me into hating him and everything for which he stands but I’m very conscious of how he’s manipulating me, which means I’m thinking about the mechanics of the book rather than believing in it. Since “manipulative” is a word with negative connotations, I should stress again that I usually like being manipulated by Dickens. In fact (heh, fact, see what I did there?), it’s what I want out of a Dickens book. But Hard Times just doesn’t succeed as well at manipulating my emotions as is typical for its author.

I believe Hard Times is the shortest and most compact of Dickens’s major novels. This is part of its appeal as, except for the stuff with Stephen Blackpool and Rachael, it stays laser focused on its creepiest and most interesting characters. That’s rather refreshing after the slow pacing and multitudinous subplots of Bleak House, a book that’s been described as labyrinthine. But there are downsides to it too, mainly that some of the character arcs could have used more time to develop. It’s rather jarring to read about Louisa abruptly resigning herself to marrying Bounderby when she’s established at the beginning of the book as being something of a rebel. I understand that she’s doing it for her brother, the only person in the world she loves, but it could have used more buildup. I also understand that she feels like there’s nothing else for her in life but in her earlier interactions with Sissy, it seems like she’s aware that there’s more to life than her father prescribes for her. Why does she just give up?

Speaking of which, do we believe Louisa when she says she’s the one who brought Tom to get a peep at Sleary’s horse riding show? Or is she saying it to protect him? Either possibility seems in character for her.

I don’t really understand the symbolism of Stephen’s dream in Chapter 13. In particular, I don’t understand why the woman he dreams of marrying “on whom his heart had long been set” isn’t Rachael. Did Dickens just want to give him depth by having him be in love with three different women at different points of his life?

Although she’s one of the bad guys, I enjoy Mrs. Sparsit and the way she trolls Bounderby. (Hey, I said I didn’t enjoy hating as much I’m supposed to enjoy it. I didn’t say I don’t enjoy hating him at all.)

P.S.

Here’s something fun to do. The next time you read a fantasy story, particularly one aimed at children, imagine how mad it would make Gradgrind. It adds to the experience. He’d really be offended by On Beyond Zebra. https://archive.org/details/onbeyondzebra00seus

LikeLiked by 3 people

“Hard Times” is a life affirming text for me. I first read it in the early 1980’s, newly away from home, and on my own. I was reading my way through Victorian literature during my one hour commute to/from work each day and “Hard Times” came upon me like a spotlight illuminating my experience and feelings about my own upbringing. Louisa, Sissy, Sleary, Dickens were articulating what I had been banging my head against since my earliest memories. My father was a strict man in a “work before play” and an overseer kind of way. My siblings and I feared him and when he was present the atmosphere in the room changed from relative ease to individual and collective stress. We were all on guard lest we be called upon to define a horse.

Reading “Hard Times” articulated for me two important things. The first was MY undefined feelings of my upbringing. Like Louisa I wondered why we kids always at the grindstone? Why weren’t we shown the beauty of math instead of just the difficulty of concepts? Why weren’t our lessons taught with connection to the world at large rather than as a set of facts, facts, facts? Why did our family dynamic seem so stilted in comparison with that of other families we witnessed? Why was everything a chore? In “Hard Times” I read my frustrations about these questions and I learned what “the one thing needful” really was – balance. For every hard lesson there needs to be a soft one, for every chore there must be an amusement, for every discipline there must be a reward.

The second thing “Hard Times” articulated for me was an explanation of my father’s Gradgrinderly behavior. I began to understand that he had reared his children based on the way HE had been taught. He didn’t talk much of his depression era past and what he did tell us was never very pretty. I began to look at my upbringing through his perspective – lots of kids, little income, long work hours. I began to view his struggle to raise his kids through a more objective lens and had to acknowledge that, while I may not agree with his methods, his motivation was always the desire to ensure we kids would be capable to succeed on our own. I learned to forgive my father for what I had hitherto seen as an overly-strict upbringing – or perhaps more correctly, forgive myself for having that view.

When it came time for me to raise my children, I worked hard to incorporate balance into their lives. I tried to make lessons fun, to show them how facts related to every day things, to instill an appreciation for the connectedness between what they learned with what they experienced, to find joy, and The Joy, in whatever was before them.

“People must be amuthed . . . they can’t be alwayth a working, nor yet they can’t be always a learning. Make the betht of uth; not the wurtht.” (Ch 6)

This message is so important that Dickens insists we “get” it by having Sleary not simply say the words but lisp them (Naslund 43). Sleary’s speech impediment is very difficult to read and thus to understand. Dickens uses this literary device in two ways. First, to emphasize his message, and second, to emphasize what is needed to implement the message. The reader has to work hard to simply understand the words Sleary is saying. “To understand what Mr Sleary says or means at all” says Naslund, “the reader must play Sleary’s role” (43). Naslund describes what every reader of Sleary goes through: “Sotto voce, the reader mouths his way through Sleary’s sentences . . . the reader has had to speak like Sleary to be Sleary for the moment, in order to grasp the meaning” (43). By forcing the reader to articulate Sleary’s words, Dickens forces the words upon the reader’s understanding. We can not help but understand Dickens/Sleary’s message.

This message is two-fold (lots of twos in this post): First – if we teach with a balanced approach, and teach balance, we create better people – we make the best of them and not the worst; Second – if we approach people from a balanced perspective (give people the benefit of the doubt, try to see both sides of a situation), we usually see them as better people – again, making the best of them and not the worst.

I like that “Hard Times” is concise, to the point – as is only fitting for its topic. As he did in “A Christmas Carol”, Dickens takes his topic by the reins and drives his message home by the most direct route. It’s a simple message but an important one. And I think, given the history of its production, “Hard Times” is just perfect.

Link to Sara Jeter Naslund, “Mr. Sleary’s Lisp: A Note on ‘Hard Times’”

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1J5XRXkxO1AcQntPP0TZaqkIxiftYB4SH/view?usp=sharing

LikeLiked by 2 people

“For every hard lesson there needs to be a soft one, for every chore there must be an amusement, for every discipline there must be a reward.”

Chris,

I was deeply touched by your description of your upbringing and the effect of reading “Hard Times” at this stage of your journey, with your mature adult perspective.

You clearly have found a way to experience compassion towards your father, while recognizing and importantly naming the imbalance.

How wonderful that you have consciously rectified the disharmony in raising your own children (and, I imagine, grandchildren)!

Thanks again for making your experience of “Hard Times” to poignant through your personal narrative.

Blessings,

Daniel

P.S. A resounding AMEN to the principle you articulated, which I cited above.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Gradgrind doesn’t want Cecilia Jupe to be called Sissy, but he seems OK with his son being called Tom. Why do you suppose that is? Is it to distinguish young Thomas from himself?

LikeLiked by 2 people

“Hard Times” isn’t a typical baggy monster we expect from Dickens, and it does get preachy. But I submit that if we think about it as an off-season Christmas book we may be more willing to forgive it it’s preachiness and begin to appreciate it on it’s own terms. As I said earlier, I really like it’s brevity; this particular topic doesn’t need wordiness. And while it is an Industrial Novel and a Condition of England novel, it isn’t like Elizabeth Gaskell’s “Mary Barton” or “North and South” or Charlotte Bronte’s “Shirley” which aim to tell stories about the lives of the people – rather “Hard Times” seeks only to point out a flaw in the system and make its plea for action, two aims wherein the fewer words the better. Dickens here does, to an extent, aim to tell the story of the people in his depiction of Stephen Blackpool’s situation. But even this thread has more of a fable feel – narration intended to enforce a useful truth – than a narrative intended to tell us about a person’s life. I hope I’m making the distinction clear. It’s more what they stand for than what they do that is important here – the deserving but suffering poor, the struggling “hands” of Industrialization. We get just close enough to Stephen, Rachael, Stephen’s wife to understand their plight but we don’t really see into their souls as we do with characters of the other novels I mentioned above. Another result of the brevity of “Hard Times”.

Mr Gradgrind is ripe for change. After finding his children peeping through the Circus tent he questions why they, who have been raised on Facts, would do so – “Then comes the question . . . in what has this vulgar curiosity its rise?” (Ch 4). It is interesting that he asks this question “with his eyes on the fire” because that is where Louisa also looks for answers (Ch 8). The posing of this question is the first chink in Mr Gradgrind’s armor of Fact.

Sleary’s Circus is glorious. I really enjoy E.W.B. Childers’s and Master Kidderminster’s conversation with Mr Gradgrind and Mr Bounderby in Ch 6. Kidderminster is terrific for calling out the pompousness of the two gentlemen, especially Bounderby. And in a really nice ironic touch, Childers presents the FACTS of Signor Jupe’s disappearance – “it’s a remarkable fact”, “I’m telling your friend what’s the fact”. Childers puts Bounderby in his place, telling him his bluster is unwelcome, immaterial to the matter in hand, and ridiculous, and dismisses him by “feigning unconsciousness of Mr Bounderby’s existence”. Childers also champions Sissy and actually plants the seed of taking charge of Sissy in Gradgrind’s mind: “If you should happen to have looked in tonight, for the purpose of telling [Jupe] that you were going to do her any little service . . . it would be very fortunate and well timed”. It seems the Circus people have hoped Mr Gradgrind would do something for Sissy since Mr Sleary mentions it almost immediately: “Ith it your intenthion to do anything for the poor girl, Thquire?”

Mr Gradgrind’s reason for assuming care of Sissy is to use her as an example to Louisa of the dangers associated with leading a frivolous lifestyle as opposed to one based upon Fact. This act of charity – though for less than charitable purposes – is another chink in Gradgrind’s armor of Fact.

That Mr Gradgrind, in Ch 8, should instruct his children to “Never Wonder” is also interesting because Mr Gradgrind does quite a bit of wondering. He wonders why Louisa and Tom would want to see the Circus, he wonders about Jupe’s desertion of Sissy, he wonders “what the people read in this library” of Coketown, he wonders about Sissy – “Somehow or other, he had become possessed by an idea that there was something in this girl which could hardly be set forth in a tabular form” – and I think he wonders at Louisa’s stoic reception of the Bounderby proposal. Granted he sees Louisa’s responses as indicative of her factual upbringing, but I think even he is taken aback by her complete lack of any animated reaction.

Bounderby describes his child self as “a nuisance, and incumbrance, and a pest” (Ch 4) and I think he remains so in his adulthood – at least Louisa and young Tom think he is. Mrs Sparsit also seems to be on her way to seeing him this way. I too enjoy watching her disappointed, spiteful, ego as it schemes against those above her whom she believes to be below her – her words say one thing but mean quite another. And she wears mittens!

LikeLiked by 3 people

“And while it is an Industrial Novel and a Condition of England novel, it isn’t like Elizabeth Gaskell’s “Mary Barton” or “North and South” or Charlotte Bronte’s “Shirley” which aim to tell stories about the lives of the people – rather “Hard Times” seeks only to point out a flaw in the system and make its plea for action, two aims wherein the fewer words the better. Dickens here does, to an extent, aim to tell the story of the people in his depiction of Stephen Blackpool’s situation. But even this thread has more of a fable feel – narration intended to enforce a useful truth – than a narrative intended to tell us about a person’s life. I hope I’m making the distinction clear. It’s more what they stand for than what they do that is important here – the deserving but suffering poor, the struggling “hands” of Industrialization. We get just close enough to Stephen, Rachael, Stephen’s wife to understand their plight but we don’t really see into their souls as we do with characters of the other novels I mentioned above.”

I’d go ever further. (Farther?) I think some critics exaggerate the extent to which Hard Times is about the plight of the workers. Don’t get me wrong. That’s a big part of the book’s story and social message and no good analysis can ignore it. But I’d argue the main story is about the Gradgrind family, which Peter Ackroyd barely touches on in his chapter on it in our supplemental reading and G. K. Chesterton doesn’t mention at all. (I’m not criticizing you for including them in the supplement BTW. I’d hate for you to think that! I’m just kind of criticizing what they wrote.)

Recently, the part of Louisa giving her father her consent to marry Bounderby reminded me of the scenes in Romeo and Juliet of Juliet pretending to her parents that she’s fine with marrying Paris. Obviously, the characters are very different but it’s similarly haunting to see parents so oblivious (intentionally so perhaps?) to their child’s real feelings and the child having given up so completely on honestly communicating with them.

LikeLiked by 2 people

A wonderful selection of comments and discussion points… thanks all.

I haven’t managed to order my thoughts in time (as usual) but I have to align myself with much of what Chris has said about this wonderful book so far 🙂 (Chris, I don’t know how you do it… it almost feels that you can see my thoughts!)

A few easy thoughts to jot down that I have been thinking of:

Is Hard Times the shortest of the long books or the longest of the short books (AKA Christmas book 6)?

Are there noticeable features shared by the group of novels published in weekly serial (whether or no Dickens planned still in monthly chunks) HT is a return to the weekly format. So far there has only been OCS and Barnaby, But A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations will inherit some of the features of Hard Times. Three Book format (3 stages of Pip’s expectations) in final volume. As well as being less ‘baggy’ to borrow Chris’s expression above. They seem to be books of greater precision and focus. Compact and efficient.

It’s a feeling I have that I may not be expressing too well here… just a question as we move along through.

Dickens often gets a bad rap for some of his female characters, but I think Hard Times has no weak links in that regard. Fascinating and well drawn characters, the lot of them.

LikeLiked by 2 people