Wherein The Dickens Chronological Reading Club (#DickensClub) introduces our twentieth group read, Little Dorrit.

(Banner Image: filtered collage of Phiz illustrations. Individual scans by Philip V. Allingham for Victorian Web.)

By Boze

Hello, friends. Is it possible to escape our upbringing? Can a better life be forged from the ashes of the old? What do the rich owe to the poor? What do families owe to each other?

But first, a few quick links:

- Historical Context

- Thematic Considerations

- A Note on the Illustrations

- Reading Schedule

- Additional References

- General Mems for the #DickensClub

- A Look-Ahead to Weeks One and Two of Little Dorrit

- Works Cited

Historical Context

“Now at last he could work on Little Dorrit, and in these final days of the old year Dickens depicted the passage of his heroine through the waste of London. The narrative seemed to enlarge and expand as he wrote it … The footsteps and the street-lamps. The rushing tide and the shadows. The sounding of the clocks. The homeless. The drunken.”

— Peter Ackroyd, Dickens

The year was 1855. The Great Exhibition had ended. Dickens was now well into the second half of his career, what later critics would dub his “mature” period. He and Wilkie Collins had become bosom friends even as his marriage fractured. Together they had visited Switzerland two years before, and now they were collaborating on a play about the doomed Franklin expedition, a play that would be known as The Frozen Deep.

On 9 February Dickens received a letter from his first love Maria Beadnell, now Maria Winter, whom he hadn’t seen in twenty years and who had furnished the inspiration for the character of Dora Spenlow. Dickens, who had reached that stage of midlife in which one is ready to embark upon a new romance—or rekindle an old one—wrote a glowing reply. Over the ensuing two weeks a lively flirtation developed via correspondence. Maria warned him that she was now old, fat, ugly and toothless, but Dickens dismissed her self-deprecations as so much Victorian faux-modesty. “Never was such a faithful and devoted poor fellow as I was,” he assured her. “… You made me wretchedly happy … the most innocent, the most ardent, and the most disinterested days of my life had you for their Sun … the Dream were all of you.” Overcome with nostalgia and a sense that his life had gone wrong somewhere, Dickens decided that Maria, after all, had been the great love of his life. Sensing a chance to remedy the mistakes of the past, he arranged for them to meet.

They agreed to a scheme whereby Maria would visit Tavistock House and call upon Catherine—and then, finding her not at home, would ask to see Mr. Dickens. The tenor of Dickens’s letters in the days prior suggests a state of all-consuming nervous excitement: “Nobody can ever know with what a sad heart I resigned you … My entire devotion to you, and the wasted tenderness of those hard years…” But in the event, Maria’s warnings proved to have been accurate. She had grown, according to Georgina Hogarth, quite fat and silly. Dickens was devastated. As he would later do with Hans Christian Andersen, he stopped replying to her letters. When she wrote to tell him that she had just lost a child, Dickens sent a perfunctory condolence and refused to see her.

The trauma of having seen his youthful illusions shattered was still on his mind as he began writing Little Dorrit. Early in the story Arthur Clennam is reunited with the now-middle-aged Flora Finching, whom Michael Slater has called “arguably his greatest comic achievement since Micawber”—a fat, silly, loquacious woman in the mold of Mrs. Nickleby. Arthur has more or less the same reaction as Dickens—“Clennam’s eyes no sooner fell upon the subject of his old passion, than it shivered and broke to pieces”—and one can’t help wondering how Maria felt when she saw herself immortalized (for the second time) as a toothless, bumbling idiot. Peter Ackroyd has written an affecting portrait of Maria later in life:

“A nursemaid in the Winter household recalled that she was ‘sweet and kindly’ in the early part of the day, but that then she would begin to drink. ‘All her refinement and restraint seemed then to break down, and it would be during these times … that she would refer to Dickens. She had a tremendous collection of his books by that time. They were to be found all about the house. When excited she would take them down from the shelves and run through their pages, commenting on their contents, interspersing them with references to the author.’ Did she take down Little Dorrit, too, and read over the descriptions of the woman modelled so unflatteringly upon her? ‘At other times she would lie on the couch and say, ‘Nurse, it was here that he used to sit,’ and I have seen her, in one of these moods, actually kiss the place on the couch, and recall something that Charles Dickens had said to her…’ A sad story, this sentimental, lost, bibulous woman—blasted, as it were, by Dickens’s fame.”

Dickens pressed on with his book, untroubled by the thought of Maria’s reaction. His surviving correspondence suggests an extraordinary restlessness during this period—he described himself as “an enormous top in full spin” and told Forster, “If I couldn’t walk fast and far, I should just explode and perish”—which makes its way into some of the descriptions in the book. He wrote each day from nine in the morning until two in the afternoon and then walked until five. The opening numbers demonstrate a distinct lack of direction—Dickens had planned to title the book Nobody’s Fault, referencing a remark that a politician of the time had made about the Crimean War, but only gradually did Little Dorrit work her way into the center of the story. As she and her father became more and more the focus of the novel, Dickens seized on the idea of altering their circumstances through an extraordinary turn of fortune.

Other ideas and characters were suggested serendipitously, the raw material of mundane events being transformed by the alchemy of his imagination. During a November walk Dickens encountered five bundles huddled against a wall which, on closer inspection, he found to be five young women. The character of Merdle, a fictional proto-type of Bernie Madoff, drew inspiration from the plight of John Sadleir, a “swindling financier” who had recently taken his own life. There’s a remarkable three-paragraph description of a Venetian apartment in the book’s second half that’s drawn from Dickens’s precise recollections of a Venetian bank. (“The house,” Dickens writes, “… looked as if it had broken away from somewhere else, and had floated by chance into its present anchorage in company with a vine almost as much in want of training as the poor wretches who were lying under its leaves.”)

Just how these images burrowed their way into the book is suggested by an anecdote in Ackroyd’s biography. Dickens had recently visited the London Zoological Gardens, where he had seen live guinea pigs and rabbits being fed to snakes: “I have ever since,” wrote Dickens, “been turning the legs of all the tables and chairs into serpents and seeing them feed upon all possible and impossible creatures.” A few months later, he described the hands of the pantomime villain Rigaud thus: “… the fingers lithely twisting about and twining one over another like serpents. Clennam could not prevent himself from shuddering inwardly, as if he had been looking at a nest of these creatures.” As ever, the strange and at times macabre sights of London proved fertile soil for his imagination.

Thematic Considerations

“There are times when within his fiction the whole world itself is described as a type of prison and all of its inhabitants prisoners; the houses of his characters are often described as prisons, also, and the shadows of confinement and guilt stretch over his pages … The Marshalsea is always there.”

— Peter Ackroyd, Dickens

In Little Dorrit, Dickens continues the exploration of his childhood trauma that he began in the early portions of David Copperfield. Claire Tomalin describes John Dickens as a “secret source of inspiration” for the character of William Dorrit, as he was for Wilkins Micawber in the former book, and some of the book’s most memorable and unforgettable sequences portray Cheapside, St. Paul’s and the neighborhood of the Borough in Southwark that surrounded the Marshalsea prison. (Personal note: Rach and I both find the Borough completely enchanting and wandered its streets in a sort of mystical reverie during our separate visits. In an interview, Peter Ackroyd—who suggests avoiding the commercial West End—lists Borough High Street and the river district as places that have managed to retain their Dickensian character into the present day.) In his working notes for Little Dorrit, Dickens writes that he wants to contrast the “New Testament” values of the heroine with the sordidness and ugliness of her surroundings, and Tomalin suggests that Amy’s unconditional love for her father was Dickens’s way of working through his own rather more conflicted feelings towards John Dickens. “She has something of Cordelia,” Tomalin writes, “who comforted her father in prison. Dickens knew his Shakespeare, and was no more tied to realism than Shakespeare. Little Dorrit is the wise child who redeems a sorry world.”

Of the book’s vicious class satire, she adds:

“The satirical parts of the book took on the great political families whose sons were given employment as by right, seats in parliament and well-paid positions as civil servants in government departments. Dickens calls them the Tite Barnacles and the Stiltstakings, and has fun at their expense, showing the young ones idling in the great Circumlocution Office and Lord Decimus Barnacle himself dispensing patronage at a carefully arranged dinner, where he is encouraged by sycophantic fellow guests to tell his only joke. It involves lengthy reminiscences about a pear tree at Eton and pairs in parliament, and he takes much pleasure in boring everyone with it. In the glow of satisfaction this gives him he offers a senior position to his hostess’s son, a young man described by his own wife as ‘almost an idiot,’ but made acceptable through his access to the fortune of his millionaire stepfather. It is a devastating piece of mockery, it angered the men Dickens was ridiculing, and some of the bad reviews the book received later were a closing of ranks with the class under attack.”

A Note on the Illustrations

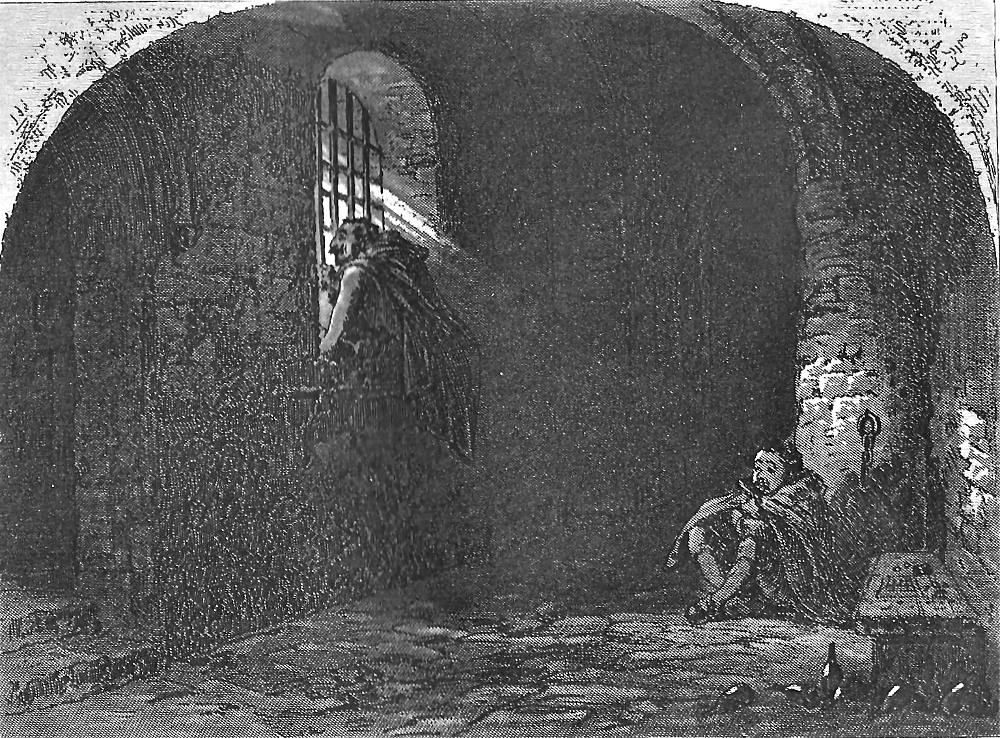

After the uniquely unillustrated Hard Times, Little Dorrit finds us back with our tried and true Dickens collaborator, “Phiz” (Hablot K. Browne). Phiz provided forty etchings–including some in the “dark plate” style of Bleak House–for the twenty monthly parts, or two etchings per part. An example of the dark plate can be seen at the right, “Birds in the Cage.”

Reading Schedule*

*note: We will read Little Dorrit over the course of 8 weeks (followed by a 2-week break), with a summary and discussion wrap-up every other week.

| Week/Dates | Chapters | Notes |

| Weeks 1 & 2: 24 Oct to 6 Nov, 2023 | Book I, Chapters 1-18 | The first 5 monthly installments of Little Dorrit were published between December 1855 and April 1856. |

| Weeks 3 & 4: 7-20 Nov, 2023 | Book I, Chapters 19-36 | The monthly installments VI-X of Little Dorrit were published between May and September, 1856. |

| Weeks 5 & 6: 21 Nov to 4 Dec, 2023 | Book II, Chs 1-18 | The monthly installments XI-XV of Little Dorrit were published from October 1856 to February 1857. |

| Weeks 7 & 8: 5-18 Dec, 2023 | Book II, Chs 19-34 | The monthly installments XVI-XX of Little Dorrit (the final month being a double number) were published from March to June, 1857. |

Additional References

Little Dorrit was famously adapted for television in 2008 as a fourteen-part miniseries. Scripted by Andrew Davies, it features Claire Foy as Amy Dorrit, Matthew MacFayden as Arthur Clennam, Andy Serkis as Rigaud, Eddie Marsan as Pancks, Alun Armstrong as Flintwich, Russell Tovey as John Chivery, Freema Agyeman as Tattycoram, Harriet Walter as Mrs. Gowan, Robert Hardy as Tite Barnacle, Sr., and Anton Lesser as Mr. Merdle.

Anton Lesser also reads the audiobook of Little Dorrit, to which Rach and I have been listening with great pleasure.

Your ‘umble Dickens Club co-hosts are also massive fans of the 1987 film adaptation of Little Dorrit, a six-hour labor of love that makes the curious decision to tell the story in two parts, the first part from Clennam’s perspective and the second part from Amy’s. Like Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon, the film makes good use of natural lighting, and the director personally made the sets and miniatures with the assistance of her husband. According to Wikipedia, “Hundreds of costumes were also sewn, made using miniature models of houses combined with special effects” to recreate Victorian London. It is one of the most soothing movies I’ve ever seen, and one that I love to revisit regularly. The cast includes Sarah Pickering as Amy Dorrit, Derek Jacobi as Arthur Clennam, Sir Alec Guinness as William Dorrit, a perfect Miriam Margolyes as Flora Finching, and David Thewlis and Heathcote Williams in minor roles. Guinness was nominated for an Oscar for his performance. Roger Ebert, in his four-star review, described the film as “so filled with characters, so rich in incident, that it has the expansive, luxurious feel of a Victorian novel.” It is, possibly, one of the greatest films ever made.

Note: After or near the completion of our eight weeks with Little Dorrit, the Adaptation Stationmaster will be leading us through a group watch and episode recap of one of these marvelous adaptations!

General Mems for the #DickensClub

If you’re counting, today is Day 659 (and week 95) in our #DickensClub! This week and next, we’ll be beginning Little Dorrit, our twentieth read as a group. Please feel free to comment below this post for the first and second weeks’ chapters, or use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter.

No matter where you’re at in the reading process, a huge “thank you” for reading along with us. Heartfelt thanks to our dear Dickens Fellowship, The Dickens Society, and the Charles Dickens Letters Project for retweets, and to all those liking, sharing, and encouraging our Club, including Gina Dalfonzo, Dr. Christian Lehmann and Dr. Pete Orford. Huge “thank you” also to The Circumlocution Office (on twitter also!) for providing such a marvellous online resource for us.And for any more recent members or for those who might be interested in joining: the revised two-and-a-half year reading schedule can be found here. If you’ve been reading along with us but aren’t yet on the Member List, we would love to add you! Please feel free to message Rach here on the site, or on twitter.

And for any more recent members or for those who might be interested in joining: the revised two-and-a-half year reading schedule can be found here. If you’ve been reading along with us but aren’t yet on the Member List, we would love to add you! Please feel free to message Rach here on the site, or on twitter.

A Look-Ahead to Weeks 1 & 2 of Little Dorrit (24 Oct to 6 Nov, 2023)

This week and next, we’ll be reading Book I, Chapters 1-18 of Little Dorrit, the installments of which were published monthly, between December 1855 and April 1856.

Feel free to comment below for your thoughts this week or use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter.

If you’d like to read it online, you can find it at a number of sites such The Circumlocution Office; you can download it from sites such as Gutenberg.

Works Cited

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens. New York: HarperCollins, 1990.

Douglas-Fairhurst, Robert. The Turning Point: 1851—A Year That Changed Charles Dickens and the World.

Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

Tomalin, Claire. Charles Dickens: A Life. London: Penguin Books, 2012.

I know we’re supposed to start reading Little Dorrit today, but I got impatient and started yesterday and I already have so much to say!

I’ve mentioned before that I think of Bleak House, Hard Times and Little Dorrit as a trilogy of sorts. To me, they represent a “period” of Dickens. They show him at his most cynical in that you get the feeling he sees mainstream society itself as corrupt, not just certain institutions within it though there’s certainly a lot of those too. But they also show him at his most broadminded as he’s willing to portray people with whom he disagrees in a positive light and, for that matter, people with whom he agrees in a negative light. I’d describe them all as “not Dickens’s best but his most interesting.”

Of the three, Little Dorrit has ended up being my favorite even though I feel like it has the faultiest structure of them all, partly for reasons mentioned by Boze. (I’m afraid I’m going to have to get into some spoilers for this paragraph. Feel free to skip.) Chapter 1 is about characters who end up being vital to the plot, but we won’t learn how for a very long time. Chapter 2 is mostly about peripheral characters. The main plot doesn’t really get started until Chapter 3 and we’re not introduced to Little Dorrit herself until the very end of it! (Some adaptations understandably start at Chapter 3.) And we don’t really learn much about her until Chapter 6. It’s initially very hard to get a bead on just what this book is supposed to be about, and Dickens doesn’t do himself many favors by starting out with the lengthy (though well written) description of Marseilles. I think that’s why I had the hardest time getting into of Dickens’s “Bleak trilogy” even though it ended up being my favorite.

In retrospect, I can appreciate how the opening chapters establish the theme of imprisonment. Rigaud and John Baptist Cavalletto are in a literal prison. The tourists are in quarantine. When she’s in a bad mood, Tattycoram feels that the Meagles household is a prison and Arthur Clennam views returning to his childhood home as returning to a prison.

The way Dickens literally translates French idioms like “mort de ma vie” or Cavalletto’s Italian name (Giovanni Baptiste) is a little odd for modern readers. But you could argue it’s more consistent and therefore makes more sense than having everything in English except for familiar expressions.

Mr. Meagles’s rant against beadles recalls Oliver Twist. “Harriet Beadle” being an arbitrary name, in particular, recalls Mr. Bumble’s alphabetical list of names for orphans. It can be helpful to keep Oliver Twist in mind during the Tattycoram subplot.

What makes Miss Wade stand out from similarly creepy Dickens characters is how relatively ordinary she seems at first. She doesn’t dress in black or have a noticeable scar or anything. She just shows up and randomly acts creepy. It’s true that Dickens describes her as having a forbidding appearance but not until after he’s already established her character through dialogue. And while Miss Wade is described as unusually masculine, she’s not nearly as cartoonishly so as Sally Brass from The Old Curiosity Shop.

The description of London on Sundays in Chapter 3 reminds me of Coketown in Hard Times. Of course, that monotony had to do with economics, and this is more a religious thing but the refrain of “streets, streets, streets,” seems to echo “fact, fact, fact.” For that matter, Arthur Clennam’s description of himself also recalls Hard Times. (“Trained by main force; broken, not bent; heavily ironed with an object on which I was never consulted, and which was never mine…always grinding in a mill I always hated…I am the…child of parents who weighed, measured, and priced everything; for whom what could not be weighed, measured, and priced, had no existence…”) Could he be seen as the good version of Tom Gradgrind Jr?

In the midst of a gloomy, ominous chapter, this exchange is really heartwarming.

“It’s no reason, Arthur,” said the old woman, bending over him to whisper, “that because I am afeared of my life of ‘em, you should be. You’ve got half the property, haven’t you?”

“Yes, yes.”

“Well then, don’t you be cowed. You’re clever, Arthur, an’t you?”

He nodded, as she seemed to expect an answer in the affirmative.

“Then stand up against them!”

LikeLiked by 5 people

Thank you, Boze and Stationmaster, for your amazing intro and first comments!

In the midst of our own time’s horrors, I’m eager to spend some hours in the somehow more human (however “bleak”) little dramas of Dickens’ London., peopled as it is with such remarkable characters.

And very much looking forward to Lesser’s audiobook. (He was a wonderful Merdle.)

LikeLiked by 2 people

Fantastic post, & great comments so far! Love the idea of BH. HT, and LD being a kind of “Bleak Trilogy.” In a way, we can say that the bleakness continues in ATTC and Our Mutual Friend, but in ATTC it is transcended by idealism and sacrifice. (Drood ends up being so much different in tone–a nod, perhaps, to the Wilkie Collinsesque style gothic detective story? It is a kind of Pickwick on drugs, if Pickwick were a “murder”–or is it?–mystery.)

I agree that there is a messiness about Little Dorrit, as both Boze and the Stationmaster have discussed here. It’s odd opening, its convoluted later revelations. (But yes yes yes, the *prison* setting of the opening beautifully sets up how everyone is in their own prison: Amy, Arthur, William Dorrit, Miss Wade…)

Messiness notwithstanding–and sometimes even *because* of the messiness–Little Dorrit is one of my top 3 Dickens novels ever, and absolutely unbeatable for its *atmosphere*. (Thank you, Dickens, for preserving the Marshalsea!) And for featuring some of his greatest creations: Amy Dorrit, the Dorrit brothers, Arthur Clennam, Flora Finching (poor Maria Beadnell–but honestly, I genuinely *LOVE* Flora, and Dickens ends up making her such a good egg, whatever “silliness” there is in her character), and I must add: MR F’S AUNT! 🙂

There is a special kind of heart here…we genuinely *love* these characters, and want to live in this world.

LikeLiked by 5 people

Interesting that you mention Miss Wade as one of the novel’s prisoners. On the surface, she seems to be one of the most independent characters. But the very independence of her personality turns out to be a prison of her own making. She won’t make friends with anyone because of her refusal to let her guard down. Like Mr. Dorrit, she’s paranoid of anyone knowing just how financially dependent on others she really is and bristles at anything that remotely resembles a slight.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Or you could say she’s like Mrs. Clennam, refraining from eating oysters just to show her son how much “reparation” she’s making for her sins.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Rach: first of all, I’m not sure what “messiness” means. Unlike most of you, though, I’ve not read the novel through, so maybe when I’m finished I’ll have a better sense of its “messy” qualities. Nevertheless, as I’m just finished with chapter 19, I can’t see where this novel is any messier than any of the novels we’ve read thus far. True to form, the novel is very dark throughout its opening chapters, the characters seem quite adrift within themselves and each other, and are really quite puzzling as to their personalities. But I think this is “Expository Dickens 101.” He spreads his narratives our with phalanxes heading seemingly everywhere, so early and with such gusto, that we can’t help but be puzzled and overwhelmed by this confusing mass of narrative strains and strange and bizarre characters.

But hasn’t this opening gambit been the nature of things Dickens?

My refrain–if I may call it–is one that comes from “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid”–“Who ARE these guys?”

Nevertheless, this is what we’ve inherited in the way of characters (so far) and as with all these (Dickens) novels we just have to make the best of it and realize that while most of these threads and characters will come together and make some sense, there will always be ambiguities (and that’s what great literature is about anyway).

But these IS so much that is interesting and beguiling in these opening chapters. Arthur first and foremost is the character that Dickens brings to the novel’s foreground and it is he, thus far, who acts as the main conduit to the narrative’s other characters. In a way, he reminds me a lot of Gupy from BH as he is a “searcher” for a number of “things”–wanting to know family secrets, seems to be interested in and is always on the alert for the various people he meets (Amy, Flora, Meagles, Mr. Dorrit, Pet–the list goes on). He’s always got his antennae out where ever he goes and with whomever he meets. Either externally or internally, we see him constantly questioning, constantly wanting to know, always looking, surmising, evaluating. He is perpetually picking up on gestures and attitudes of other characters. AT the same time he is constantly evaluating himself, second guessing himself, berating himself, undercutting himself and even overevaluating his aspirations and abilities. He’s moody, serious, seldom content, and seems starved for knowledge.

In short, he’s such an interesting character and represents–for this novel–what Henry James would call the “Lucid Reflector.” In many ways he reminds me of one of my favorite James protagonists–Lambert Strether, the ostensible “hero of THE AMBASSADORS….

LikeLiked by 3 people

Maybe this will help you understand why I find the opening chapters of Little Dorrit slow going, on my first read anyway. Oliver Twist and David Copperfield begin (respectively) with the births of Oliver Twist and David Copperfield and the books are about their lives. The openings of Nicholas Nickleby and Martin Chuzzlewit don’t really introduce the main characters, but they do introduce us to the Nickleby and Chuzzlewit families which are also the focus of the books. Bleak House is a critique of Chancery and the first chapter is a description of that institution. It’s hard to tell from the beginning of Little Dorrit just what the book is supposed to be about. In retrospect, you can see it introduces the motif of imprisonment but, as Father Matthew says, the prison in Chapter 1 is pretty different from the Marshalsea.

Of course, all this is subjective, and a matter of personal taste and I hope I don’t sound like I’m trying to lessen anyone’s enjoyment of this book.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fantastic thoughts, Lenny!!! (SO marvelous to have you back, by the way–we missed you!!) I think my own word, “messy,” was…messy! When I talked about its messy opening (and I say this with affection, because I adore this book more than almost any other Dickens) is that it is…strange. Set in Marseille, with characters whose importance to the story won’t be remotely known or glimpsed at for a long time…it seems such an odd beginning, even for Dickens.

As to the messiness of the end–again, written with the greatest affection–I’m referring mostly to the revelations (which I won’t mention here, for spoilers) that are given towards the end by both Mrs Clennam and Rigaud. How the Dorrit story is related to the Clennams’. (On this note, there is a very helpful little reader video which explains the whole convoluted relationship-drama very well!) Again, it IS, agreed, typical Dickensian wildness, but…even more so??? 🙂

LikeLiked by 3 people

“Do you consider,” she returned, without answering his question, “that a house serves no purpose, Arthur, in sheltering your infirm and afflicted—justly infirm and righteously afflicted—mother?”

This is matter of interpretation, but my head canon is that when Mrs. Clennam interrupts herself to clarify that she believes she deserves her infirmity and afflictions, it’s because she’s really angry at God for them and is checking herself. If so, it’s an intriguing lapse from her usual inflexibility.

I know there are readers out there, like this group’s own Lucy, who dislike Dickens’s purely heroic heroines, but I love the character of Little Dorrit. Here’s something I wrote about her in a blog post about an adaptation of this book. (I don’t want to link to it because I might be recapping the adaptation at the end of this reading group, and it gives away a lot of my opinions. I’m pretty I’ve already shared it with this group though.)

“Generally, I don’t hate Dickens’ self-effacing heroines as some do, but I concede that few of them are the best characters in their stories. I’d argue that the virtues Dickens praised in these heroines, of quietness, gentleness, humility, patience and forgiveness, are genuine virtues and if they aren’t always the most useful virtues for every situation, well, neither are the virtues of Dickens’ male heroes. But there’s a case to be made that Dickens himself was too loud, too bombastic, too egotistical, too impatient and too bitter to really make these virtues appealing. Little Dorrit, in my opinion, is an exception. Her humility feels like genuine humility rather than the showy humility of Dickens’ other heroines at their worst.”

Dickens gives Little Dorrit’s dialogue a kind of quiet dignity that, for all his strengths of characterization strikes as rare for him. Every other member of her family (except for her uncle, I guess,) is always clamoring for respect and insisting on their dignity which makes them come across as pathetic. But, ironically, by focusing her attention on others and quietly fading into the background Little Dorrit is the only one with real dignity.

Compared to similar Dickens heroines, like Florence Dombey or Madeline Bray, Little Dorrit is also relatively less delusional about her unworthy father and siblings. Understanding her father’s circumstances, she has a lot of compassion for him and is proud of how he’s held up all these years and made a new life for himself. But she also understands, on some level, that his behavior is contemptible and is embarrassed by him. Actually, that’s not true. She’s embarrassed for him. (Agnes Wickfield was arguably a bit like this too.) Because her love is relatively clearheaded (if it’s a bit delusional, I think we can blame this on her upbringing), it’s easier to empathize with it and gives the readers more compassion and tolerance for the other Dorrits than they might have otherwise.

I’m sorry that the last paragraph sounds like I’m bashing Dickens heroines who are a bit more delusional in their love for their fathers. That’s an interesting dynamic to explore and it can be pretty relatable since most, if not all, of us want to think well of our parents. I just think the dynamic between Little Dorrit and her family is more interesting and has some dramatic benefits.

The book will later stress how Little Dorrit inspires Arthur Clennam but something I never noticed until this read is how he brings out a new side of her too. In Chapter 9, after giving a long speech about how she feels about the Marshalsea prison, she says, “I did not mean to say so much, nor have I ever but once spoken about this before. But it seems to set it more right than it was last night.” Shortly afterwards, when she tells him how hopeless it is to untangle her father’s affairs and liberate him, Dickens writes that “she forgot to be shy at the moment.”

Arthur Clennam’s ordeal at the Circumlocution Office reminds of me seeking financial aid for college. I spent so much time on hold on the phone. Of course, I realize there were practical reasons for that, and I did get some aid eventually, so I can’t say it was a total waste of time or anything. Still….

Although Pecksniff is the more famous of Dickens’s two-faced villains, I enjoy Casby a lot more. (Of course, neither character is particularly famous at this point in history, but he was at one point.)

Tonally, Little Dorrit isn’t that far from The Old Curiosity Shop, which I’ve dismissed as too weepy. But the melancholy of Little Dorrit works for me much better. Partly, I think that’s because the writing is better. It’s also because the comedic supporting characters are much funnier. For all the somberness of the book’s tone, it has some of the most hilarious material in all of Dickens. I love Flora Finching, (though our first two weeks’ reading don’t show her at her best), Pancks (though he’s even less at his best) and Mr. F’s Aunt.

LikeLiked by 5 people

Stationmaster, that I dislike Dickens’s purely heroic heroines is not quite right. I’ll explain what I meant when I have a chance – now, rushing.

LikeLike

Stationmaster–you make so many lovely and meaningful comments about the “character” Little Dorrit. I especially relate to this comment–“Understanding her father’s circumstances, she has a lot of compassion for him and is proud of how he’s held up all these years and made a new life for himself. But she also understands, on some level, that his behavior is contemptible and is embarrassed by him.” I think in this regard you present her as someone who is a realist when she considers her father’s predicament but also one who, in spite of her dissatisfaction with her father, still deeply loves him and displays her love both verbally and physically.

Thus, I can’t help but compare and contrast her with Little Nell and the tragic and trying relationship she has with her grandfather. The minute she leaves the curiosity shop and is on the road with him, she is desperately trying to keep him happy and alive through all the circumstances they experience together. But for some reason, I think, she is fighting a losing battle with him and against all the perils they suffer through. Of course she is a MUCH younger character than Amy and really, as much as she tries, doesn’t have the resources or maturity that Little Dorrit has. We might even go so far as to say that the characterization of Amy is a kind of Nell REDUX.

Even though I’m coming to LITTLE DORRIT for the first time, I fele like she has the strength of mind and body to be a survivor.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think it’s interesting to see Little Dorrit as a loose remake of The Old Curiosity Shop. I guess it’s really only the characters of the heroine and her father figure that they have in common. (Well, that and the tone, I’d argue, to an extent.) But it’s interesting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mrs. Clennam and her son seem like opposites so it’s interesting how Dickens points out a similarity between them through Little Dorrit’s eyes in Chapter 14. “The brown, grave gentleman, who smiled so pleasantly, who was so frank and considerate in his manner, and yet in whose earnestness there was something that reminded her of his mother, with the great difference that she was earnest in asperity and he in gentleness.”

It’s also interesting, given how Dickens stresses the childlike aspects of Little Dorrit, that he twice reminds us in Chapter 14 that she’s really an adult, first by her initially negative reaction to Arthur Clennam referring to her as his child and second by the words of the prostitute. “‘You are kind and innocent; but you can’t look at me out of a child’s eyes.” Perhaps Dickens did this because Little Dorrit is one his most romance-driven stories, arguably anyway, and he needs readers to keep in mind that Little Dorrit is a sexual being.

I never realized until this read that this passage from Chapter 15 foreshadows Rigaud.

“Strange, if the little sick-room fire were in effect a beacon fire, summoning some one, and that the most unlikely some one in the world, to the spot that MUST be come to. Strange, if the little sick-room light were in effect a watch-light, burning in that place every night until an appointed event should be watched out! Which of the vast multitude of travellers, under the sun and the stars, climbing the dusty hills and toiling along the weary plains, journeying by land and journeying by sea, coming and going so strangely, to meet and to act and react on one another; which of the host may, with no suspicion of the journey’s end, be travelling surely hither? Time shall show us. The post of honour and the post of shame, the general’s station and the drummer’s, a peer’s statue in Westminster Abbey and a seaman’s hammock in the bosom of the deep, the mitre and the workhouse, the woolsack and the gallows, the throne and the guillotine—the travellers to all are on the great high road, but it has wonderful divergencies, and only Time shall show us whither each traveller is bound.”

It’s interesting that in her first scene with Miss Wade, Tattycoram seemed to fear her but in Chapter 16, she mentions her when she didn’t have to do so. (Yes, Mr. Meagles asked about Miss Wade, but he probably didn’t expect anyone-and certainly not Tattycoram-to answer.) As someone with anger issues, I relate to Tattycoram.

From our modern perspective, it’s also interesting how Dickens presents Henry Gowan’s laziness and cynicism as signs that he’s evil. Nowadays we expect young people to be lazy and cynical, perhaps because we have the internet to remind us of all the reasons to for cynicism.) Sometimes I wonder if Dickens wasn’t really right though I’m too lazy and cynical myself to make this stand. It’s definitely something Dickens believed though because Jack Maldon in David Copperfield and James Harthouse in Hard Times are very much in Gowan’s mold.

I love Clarence Barnacle! I think he’s one of Dickens’s most underrated comic relief characters.

Mr. Meagles intrigues me for much the same reasons that Sir Leicester Dedlock of Bleak House does. On the one hand, Dickens portrays him as a lovable, generous character, very much in the Fezziwig mold. On the other hand, he clearly portrays many of his views, such as his jingoism, in a negative, satirical light. He’s a supportive friend to Daniel Doyce yet he still stereotypes him as having a bad head for business because he’s an inventor. He rails against the Circumlocution Office yet he’s still in awe of the Barnacle family. He’s suspicious of Gowan as a suitor for his daughter yet (as we’ll see) he’s still impressed by his status as a gentleman. Mr. Meagles seems like a good example of what modern people call implicit bias. (I think that’s what they call it. I’m not an expert on all the buzzwords; I feel like they just end up getting in the way of reasonable discourse. But it’s cool that Dickens was writing about something long before people came up with a buzzword for it.)

Speaking of not being able to surrender misconceptions, for all the humor of Flora, there are some parallels between her and Dickens’s more tragic characters like Pip in Great Expectations. Her dialogue shows that she knows that the romance between her and Clennam is over and that the appropriate thing for her to do is gracefully bow out. But she can’t seem to let go of the hope that they’ll eventually get back together. It’s pretty sad. (Was that how it was for Maria Winter nee Beadnell? Or was Dickens just projecting that onto her in his bitterness? Who knows?)

It’s interesting to compare John Chivery to Toots from Dombey and Son and Guppy from Bleak House. (Maybe I shouldn’t classify Guppy with the other two since he’s more of a negative character, but it feels fitting.) Dickens describes his outfit as “ridiculous” and his personality as “sentimental.” His dialogue has the rhythms of one of Dickens’s comedic characters with the quirk of fantasizing about inscriptions for his tombstone. But it’s a lot harder to laugh at him than it is to laugh at Toots or Guppy. It’s easier to simply pity him, especially as the book proceeds and he ends up playing a positive role in the drama. Maybe that’s because so much of the book is emotionally driven that it’s hard to tell why we should empathize with Arthur Clennam and Little Dorrit’s romantic angst and not Chivery’s. I wonder how much of this was intentional on Dickens’s part and how much the character of John Chivery “got away from him.”

LikeLiked by 3 people

Well, Stationmaster, I just HAVE to make a comment about the LITTLE DORRIT quote you give describing the “sickroom.” Yes, I agree, it does foreshadow the coming of Riguad: the beacon of light, like the candle to a moth, will draw him in. To his destruction, I don’t know yet. But what REALLY hits me about this quote is the voice of the narrator with his virtuoso philosophic note that is not only addressed to the supposed characters in the novel, but to his audience at large and maybe to the entire world and its “travelers.” In fact, this is like something out of Bunyan’s PILGRIM’S PROGRESS, with its scope and depth, with its allegorical tone and message.

I make note of this because one of the things I’m seeing a lot of in LITTLE DORRIT is the constant intrusions the narrator makes into the narrative frame of the novel. It’s there, and I’ve really noticed it a lot–these intrusions–but I haven’t read enough of the story to get a sense of why it’s there and what it means. But just look at this particular segment:

“The post of honour and the post of shame, the general’s station and the drummer’s, a peer’s statue in Westminster Abbey and a seaman’s hammock in the bosom of the deep, the mitre and the workhouse, the woolsack and the gallows, the throne and the guillotine—the travellers to all are on the great high road, but it has wonderful divergencies, and only Time shall show us whither each traveller is bound.”

Here, the narrator seems to be flexing his authorial muscles, almost out of nowhere, to give us a kind of warning about the vagaries of time and the ways in which people will be bound by the decisions they make and the ways in which these moments in their lives with define their individual fates. One of the key words here is “divergences”–and its qualifier “wonderful”–which to me indicates that sometimes there is as great deal of unpredictability that will ultimately determine our destiny.

I guess the key question for me, here (and maybe for us readers)–is why this narrator’s intrusion and what does it do for this particular segment of the novel? Does it heighten it? Does it underscore some ideas that are or will be important later on. Or is it just the author showing his editorial and authorial chops?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Inimitable friends, just popping in to say what a DELIGHT it is — after a very busy five months in which I’ve hardly had time to pick up a book! — to once again immerse myself in Dickens with all of you. I picked up Little Dorrit this week and have been quite swept off my feet by this exciting, touching, beautiful story. Maybe it’s this time of year which is making me more sensitive to spookiness of every sort, but I was surprised by the many unsettling moments in the first ten chapters: the mysterious young Miss Wade with her portentous remarks about fate in Marseilles, the icy Mrs. Clennam reciting the imprecatory psalms against her enemies from the prison of her sick-bed, the doppelgänger of Mr. Flintwich glimpsed by Affery with dread in the dead of night! Nobody does Victorian gothic quite like Dickens!

The several kinds of imprisonment developing so far make for a salient theme. Of course we start with the brutish conditions of Rigaud and Cavalletto in their little cell, then — in quick succession — the quarantine, the Marshalsea (with its delightful little society of debtors and smugglers—seems a far cry from the conditions of Marseilles!), and the Clennam house, which was an oppressive prison for Arthur as a boy and in which Mrs. Clennam has now imprisoned herself (possibly in self-imposed penance?)

Like the Stationmaster, I wonder why Dickens began this novel with Rigaud and Cavalletto. Boze mentions that “only gradually did Little Dorrit work her way into the center of the story,” so maybe D. had quite a different story in mind at the beginning centering on these two, which was gradually eclipsed by the emergence of Amy Dorrit at the heart of the narrative. Still, my working theory is that the initial prison scene, like an overture, establishes the recurring central theme of the story. Almost all of the characters we have seen so far are imprisoned in one way or another — with the possible notable exception of Arthur Clennam. At the end of chapter nine, we get the repetition of the caged bird image from chapter one, like a musical motif reminding us of the overture. This is a story about prisons and prisoners, and our Little Dorrit “the small bird, reared in captivity,” who has never yet spent a night outside her cage.

I laughed out loud at this passage: “The smugglers habitually consorted with the debtors (who received them with open arms), except at certain constitutional moments when somebody came from some Office, to go through some form of overlooking something which neither he nor anybody else knew anything about. On these truly British occasions, the smugglers, if any, made a feint of walking into the strong cells and the blind alley, while this somebody pretended to do his something: and made a reality of walking out again as soon as he hadn’t done it—neatly epitomising the administration of most of the public affairs in our right little, tight little, island.”

And I was touched by this scene with Arthur with Amy Dorrit and Maggy in the street, when their mean surroundings are transformed by the love he perceives Amy has shown to her poor companion: “The dirty gateway with the wind and rain whistling through it, and the basket of muddy potatoes waiting to be spilt again or taken up, never seemed the common hole it really was, when he looked back to it by these lights. Never, never!”

Final note: the version narrated by Juliet Stevenson in the Audible Dickens Collection is really excellent and free with an Audible subscription!

See you all in the next wrap-up. I’m excited to see where this story leads.

LikeLiked by 6 people

It’s great to have you back.

LikeLiked by 3 people

So glad to have you back, Padre!

Like you, I am enraptured by LD. So much so—I had never read it before, only seen the two wonderful TV adaptations—that I believe it is rapidly becoming my favorite Dickens. (Heretofore BH.)

I think it’s the soaring writing. From the opening sun-staring description of Marseilles and the relentless “prison” metaphors, to the philosophically revelatory characterizations, by way of dialogue, the whole thing’s just brilliant.

For example, and just for starters, in the scene on the ship, Arthur’s self-description to Mr. Meagles of a perverted religious upbringing:

“’I am the son, Mr Meagles, of a hard father and mother. I am the only child of parents who weighed, measured, and priced everything; for whom what could not be weighed, measured, and priced, had no existence. Strict people as the phrase is, professors of a stern religion, their very religion was a gloomy sacrifice of tastes and sympathies that were never their own, offered up as a part of a bargain for the security of their possessions. Austere faces, inexorable discipline, penance in this world and terror in the next—nothing graceful or gentle anywhere, and the void in my cowed heart everywhere—this was my childhood, if I may so misuse the word as to apply it to such a beginning of life.’”

Then, Miss Wade’s (to me) bone-chilling response to Mr. Meagle’s goodbye-comment that they should likely never meet again:

“‘In our course through life we shall meet the people who are coming to meet us, from many strange places and by many strange roads,’ was the composed reply; ‘and what it is set to us to do to them, and what it is set to them to do to us, will all be done.’

“There was something in the manner of these words that jarred upon Pet’s ear. It implied that what was to be done was necessarily evil, and it caused her to say in a whisper, ‘O Father!’ and to shrink childishly, in her spoilt way, a little closer to him. This was not lost on the speaker.

“‘Your pretty daughter,’ she said, ‘starts to think of such things. Yet,’ looking full upon her, ‘you may be sure that there are men and women already on their road, who have their business to do with you, and who will do it. Of a certainty they will do it. They may be coming hundreds, thousands, of miles over the sea there; they may be close at hand now; they may be coming, for anything you know or anything you can do to prevent it, from the vilest sweepings of this very town.’”

Yikes! Especially knowing what I know (from the TV adaptations) of what’s coming, the malice of it all, as if it will all be a web of Miss Wade’s own supercilious and malignant devising, is simply stunning.

LikeLiked by 4 people

SO marvelous to have you back, Fr Matthew!!! Wonderful comments. And DANA…THRILLED that this is becoming perhaps your favorite Dickens???!!!! YAY!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Dana: In a response I wrote to Stationmaster (above) about one of the “authorial” quotes regarding the sickroom–where the narrator goes in some depth about various travelers’ destinies (a kind of echo of PILGRIM’S PROGRESS), I noted the philosophical tone of the piece. And it seems, here, Miss Wade’s “jarring” comments are (in some ways) pretty much an extension of this philosophical vein. However, where the narrator of the “sickroom” seems to be referring only tangentially to the action, characters and place in the novel, here Miss Wade seems to be directly promoting a warning not just to Pet but to the world at large. First, “in the course of life” gives the reader a sense of her almost sermonizing about the world and life at large, but then her language shifts to something more personal, “Your pretty daughter,” and things begin to bite very deeply.

Rather than keep her discourse at a fairly general level, then, Miss Wade begins to charge her verbal pyrotechnics and make a direct assault on Minnie. And this aggressive stance really does frighten us (readers) as well as her intended victim.

So, I’m caught up, as a reader by a number of thoughts, here: Miss Wade seems to be a kind of extension of the narrator and the narrative philosophizing which I noted earlier, a character who also becomes an extension of the narrator’s “critical

acumen”–able to “see through” the artificiality of another character, but also a knowing and astute character in her own right, but yet represents personality who really lacks the “social skills” to be attractive TO THE READER as a fictitious individual in a novel as well as representing a repellent and scary character in the world of the novel itself.

Whew! The complexity of Dickens writing is really quite something! (And I feel like I’ve just scratched the surface, here!)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Perhaps because I’ve read “Little Dorrit” a few times now and know where it’s going and how it all fits together I don’t find the beginning to be messy or convoluted. Rather I find it hits just the right mode and tone of giving us the foundational information we need of the many disparate characters, situations, and themes it contains. It doesn’t linger over one set of characters too long for us to forget about the others. There is a lot going on here – it is at once expansive (in its comments on the whole of Society and in its settings of various geographic locations) and claustrophobic and confining (both literally and figuratively) – and I think Dickens does an exceptional job of keeping all the ducks lined up as he moves them into formation.

We meet a lot of characters rather quickly and what I notice most obviously about them are contrasts in selfishness and selflessness. The first instance is shown through the eyes of the jailer’s little daughter and her reaction to Rigaud versus her reaction to Cavaletto:

“The child put all these things between the bars into the soft, Smooth, well-shaped hand, with evident dread—more than once drawing back her own and looking at the man with her fair brow roughened into an expression half of fright and half of anger. Whereas she had put the lump of coarse bread into the swart, scaled, knotted hands of John Baptist (who had scarcely as much nail on his eight fingers and two thumbs as would have made out one for Monsieur Rigaud), with ready confidence; and, when he kissed her hand, had herself passed it caressingly over his face.” (Bk 1 Ch 1)

Another instance is that of the Plasterer Mr Plornish who, upon his release from the Marshalsea, offers Mr Dorrit a testimonial:

‘It ain’t much,’ said the Plasterer, putting a little pile of halfpence in his hand, ‘but it’s well meant.’

The Father of the Marshalsea had never been offered tribute in copper yet. His children often had, and with his perfect acquiescence it had gone into the common purse to buy meat that he had eaten, and drink that he had drunk; but fustian splashed with white lime, bestowing halfpence on him, front to front, was new.

‘How dare you!’ he said to the man, and feebly burst into tears.

The Plasterer turned him towards the wall, that his face might not be seen; and the action was so delicate, and the man was so penetrated with repentance, and asked pardon so honestly, that he could make him no less acknowledgment than, ‘I know you meant it kindly. Say no more.’

‘Bless your soul, sir,’ urged the Plasterer, ‘I did indeed. I’d do more by you than the rest of ‘em do, I fancy.’

‘What would you do?’ he asked.

‘I’d come back to see you, after I was let out.’

‘Give me the money again,’ said the other, eagerly, ‘and I’ll keep it, and never spend it. Thank you for it, thank you! I shall see you again?’

‘If I live a week you shall.’

They shook hands and parted. The collegians, assembled in Symposium in the Snuggery that night, marvelled what had happened to their Father; he walked so late in the shadows of the yard, and seemed so downcast. (Bk 1 Ch 6)

Before this time reading I hadn’t appreciated the significance of Mr Plornish’s testimonial. This is the Biblical lesson of the widow’s mite – the coppers Plornish gives are more than he can monetarily afford, but he gives them out of true charity and respect. On top of this, he gives the even greater gifts of discretion – shielding the distraught Mr Dorrit from prying eyes – and friendship – pledging to return to visit which is “more . . . than the rest of ‘em do”. Plornish holds true to his pledge and he and his family become an outside source of support for Amy Dorrit and, thus, her father.

In contrast to Mr Plornish is the whole of the Circumlocution Office and the Barnacles who want nothing to do with anyone and whose only “work” is to dissuade anyone from doing anything with them or for doing any “work” for them.

Also this time reading I appreciated how sensitive Arthur is toward Amy after he rather insensitively follows her into the Marshalsea. It is clear it never dawned on him that she might have a reason for keeping herself aloof from notice. Yet the moment he sees her reaction upon his entrance into her father’s room he seems to regret his intrusion and to try to mitigate its effect on her sensibilities: “She started, coloured deeply, and turned white. The visitor, more with his eyes than by the slight impulsive motion of his hand, entreated her to be reassured and to trust him.” (Bk 1 Ch 8) His apology to Little Dorrit explains his purpose – ‘Pray forgive me,’ he said, ‘for speaking to you here; pray forgive me for coming here at all! I followed you to-night. I did so, that I might endeavour to render you and your family some service” – and she begins to trust him, especially after he speaks with her on the Iron Bridge the next day (Bk 1 Ch 9).

I have to say I’m not a big fan of Miss Wade – perhaps because Dickens has written her so well. But I find her tedious, unsympathetic, and much less interesting than either Rosa Dartle or Edith Granger-Dombey. She goes out of her way to make people feel uncomfortable for the sake of making them feel uncomfortable. Though during quarantine she “had either withdrawn herself from the rest or been avoided by the rest” she seems to jump at the opportunity of injecting her bitterness into the conversation between Mr Meagles and Arthur (with Riguad sitting beside her). (Bk 1 Ch 2) And while she may seem to sympathize with Tattycoram, that frustrated, angry young girl is right to be afraid of her. But more on this as we get further into the novel.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Chris: I agree with you about the novel’s “messiness” and you sum up your conclusion with the following quote which I love:

“…and I think Dickens does an exceptional job of keeping all the ducks lined up as he moves them into formation.”

To a great extent, this seems to be his organizing principle in the “later novels” say, following, NICKLEBY. His openings appear, at first, so scattershot, and for us readers they are often confusing, disorienting, and simply nerve-racking. But eventually, the novel and its characters and circumstances start to come around and order themselves into some kind of sense. Maybe part of our anxiety about this confounding structure has to do with the SOLIDITY with which he sets up these little “worlds” and their characters during these opening chapters. In Marseille, for instance, he introduces IN SOME DEPTH the business and characters in the prison and in the Quarantine facility so that we readers are ready for the novel to start there, and then abruptly switches the narrative to another “world” (Arthur’s mother’s house) which he again presents in great detail, and we think, Oh–that’s where this novel is going, and then another switcheroo to another “world in depth” (Marshalsea) and there we are, in our confusion–trying desperately to figure out “Where is this novel taking us.” In retrospect, as we look back at this opening, it all makes perfect sense. But at the beginning, we readers can’t help but be jolted by these rapid movements from place to place, circumstance to circumstance.

And thus, as you say, Chris, the “ducks” begin to line themselves up–so very nicely!

LikeLiked by 3 people

It’s interesting that you compare Miss Wade to Edith Dombey since I see the former as a villain (at this point anyway) and the other as more sympathetic.

Anyway, I can’t blame you for thinking her a failure of characterization as she’s…a very weird character. LOL. I admit thought I find her weirdness fascinating. I do have some issues with the subplot of Miss Wade and Tattycoram but, like you say, we’ll get to those later. It’s really hard for me to talk about this book without alluding to future events in it. LOL.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I compare Miss Wade with Edith only in that they are two of Dickens’s “angry women”. And, I don’t think Miss Wade a failure, in fact, I think she’s a very well-drawn character – I just don’t care for her, mainly because I think she protests too much and, as I said above, because she makes people feel uncomfortable for the sake of making them uncomfortable. But that’s her part and Dickens must, of course, have written her very well to make me dislike her as I do.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Dear ‘umble Club Hosts and Inimitables All!

What a marvelous introduction to “Little Dorrit,” which is such a masterpiece. Thank you!

First off, I love the opening questions you pose, Boze (that’s a rhyme . . . I must be a poet and not even know it).

Second, a couple of thoughts.

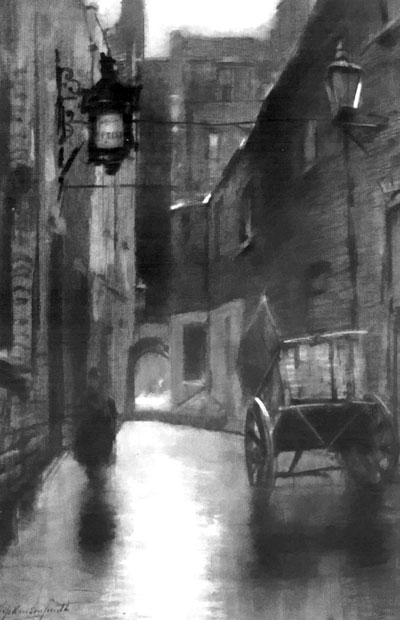

1. “The Marshalsea Prison” image: Do you know what the medium was for the wonderful opening image of the prison by Francis Hopkinson Smith? Very atmospheric!

2. Dickens’ shadow: I appreciate the straight-forward rendering of the way in which the restless Dickens treated Maria Winter, his one-time love. Ouch. We know that his literary brilliance is not dimmed by these realities, but it does remind us that he was a genius and a very generous philanthropist, and no saint.

3. “The Frozen Deep”: I’m wondering if anyone is familiar with this play. Is it a worthy literary effort?

4. Alchemy: Great image—“mundane events being transformed by the alchemy of his imagination”! Excellent.

5. Life’s a prison: That is a haunting phrase—“The Marshalsea is always there.” Well worth pondering the ways in which our memories and inner lens keeps us held captive in our self-made prisons.

6. Amy, a Cordelia: I hadn’t thought of that parallel, but it works. Women who are fiercely devoted to their somewhat foolish and self-occupied fathers.

7. “New Testament values: It does seem true that Amy embodies the self-giving compassion, kindness, and long-suffering depicted in the Gospels.

Thanks much for this wonderful launchpad into the world of Dorrit!

LikeLiked by 4 people

About to embark on my reading of Little Dorrit, the one Dickens novel that I have never really taken to, and I can’t think why, so I am looking forward to reading it with a new contextual framework. I thought it really interesting that the friendship with Wilkie Collins is framed with the words ‘even as his marriage fractured’ as I think Wilkie’s own personal situation in many ways acted as a kind of incentive for Dickens to see his marriage as something that he could walk away from.

In terms of the Frozen Deep, I am setting out an abbreviated version below how I referred to it in my Masters dissertation:

During 1856, as he continued writing the instalments for Little Dorrit, Dickens also commenced work on the putting on of a play written by Wilkie Collins. That play was called The Frozen Deep. It would prove to be the catalyst that would compel Dickens to act upon his searing sense of unhappiness and domestic ennui, and separate from his wife.

As Collins neared completion of the script in October 1856, Dickens grew, as Lycett observes, ‘visibly excited’, growing a beard in anticipation of the role of Richard Wardour, the Arctic explorer of the terrible icy regions, and set about transforming the school room of his home, Tavistock House, into a suitable theatre. In January 1857, a select audience, comprising the ‘highest celebrities in law, art, and fashion’, including the Chief Justice of England, the president of the Royal Academy, and professional reviewers, watched an amateur performance of this play, with Dickens ‘rending the very heart out of [his] body’ playing the role of Richard Wardour, a man who is defined by his appetites, including his love for the character of Clara Burnham. It is a clever play on names, the ardour of Wardour being disguised within his own name, and Clara’s surname, a close homophone for ‘burn him’ evoking a sense of her power over him, her potential to consume him. In the play, Wardour was a man who had been disappointed in love, believing himself to be engaged to Clara, who was engaged to another man, Frank. As Tomalin notes, from the very outset of the putting on of the play, Dickens was intent on throwing himself into the part of a man who overcomes his own wickedness and ends by making the supreme sacrifice. In taking on this role, Dickens was able to find some relief from his marital unhappiness. Months after the final performance, he would still refer to the relief that his part in the play had given him.

Hager states that the story of The Frozen Deep is one of ‘renunciation and heroic self-sacrifice. It is also a story of unrequited love, broken engagements, and a kind of ferocious self-discipline’. It was a story that spoke to the very heart of the struggles that Dickens himself was enduring at that time. Tomalin observes that the plot of The Frozen Deep was ‘preposterous and the writing hardly better’, but it was the performance, not the script, that excited Dickens, and he was able to transcend the limits of that script. Brannan argues, in his analysis of the 1857 script that this was because Dickens’s conception of the play was independent of Collins’s words, growing from his sense of dissatisfaction with his personal life and his increasingly painful marriage.

In the play, Dickens, through giving voice to the character of Wardour, who values the icy plains of the Arctic because they have no women in them, is able to indulge in a diatribe of blaming women for his unhappiness, the ‘disappointment which had broken [him] for life, though such lines as ‘The only hopeless wretchedness in this world, is the wretchedness that women cause,’ turning to the audience, commanding them to look at him:

Look at me! Look at how I have lived and thriven, with the heart-ache gnawing at me at home… I have fought through hardships that have laid the best-seasoned men of all our party on their backs.

As the play continues, Wardour despairs over his own thoughts, in an echo of Dickens’s own inner turmoil:

If I could only cut my thoughts out of me, as I am going to cut the billets out of this wood!… I don’t like my own thoughts – I am cold, cold, all over.

Here speaks, as Ackroyd observes, the boy, the adolescent and also the man, each stage of Dickens’s life marked by the supposed enmity or failure of women, including his mother, his sister, Maria Beadnell, and his wife. They are lines that seem to have come from some ‘deeper source within him’. Through the conduit of the stage, Dickens was able to vocalise his own misery. Dickens acted the role with such intensity that he was often near collapse after the performances, and he relished in the reaction of his ‘excellent’ audience, commenting to his friends that he had never seen audiences so affected, and delighting in the ‘wonderful power of crying’ he was able to call from them. There can be no doubt that Dickens carried the play, his ‘finely executed’ performance being lauded by the critics, as evidenced by the fact that later productions of the play failed. When the play was revived in 1866, without Dickens in the role of Wardour, it flopped, although at the time Collins believed that the failure of the play might have had something to do with the timing, being forced onto the stage in October, rather than closer to December when it may have benefitted from the Christmas market. It was also reviewed and rewritten by Collins in 1874, but again, failed to gain any of the popular or critical success it had enjoyed in 1856 or 1857 when Dickens had played the part of Wardour. Tomalin suggests that it was the presence of Dickens that made up for the defects of the play. Dickens, and his innate misery, were the driving forces behind the initial success of the play.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thank you so much for that context on The Frozen Deep, Deborah! This so well sets up Dickens’ inspiration behind his next novel, too, A Tale of Two Cities, where he refines (and in my opinion, transcends and perfects) the Wardour character in Sydney Carton. Amazing how Dickens is so well able to create such art and symmetry out of the messiness of life, his own emotions. Agreed here with Daniel…I do feel so sorry for several of the women in his life. To live within the Dickens orbit must have been staggering…a kind of whirlwind whose energy, however marvelous for his readers, must have been sometimes hellish to live with.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Deborah,

I deeply appreciate this deep-dive look at “The Frozen Deep.”

I am dumbstruck by Dickens’ stance towards the women in his life–apparently, a “victim” of his own expectations and passions.

It feels profoundly sad to me–something haunting him on such a deep level. And, my heart goes out to the women in his life, who likely suffered greatly from Dickens’ dissatisfactions.

While the play appears not to have had lasting appeal nor merit, what it showcases about Dickens is compelling–tragic as it is.

Thanks again!

Daniel

LikeLiked by 2 people

This esseay/reflection by poet David Whyte captures my sense of Dickens’ tragic “haunting” regarding key women in his life.

HAUNTED

is a word that denotes an unresolved parallel, a presence that is not quite a presence; a visitation by the as yet unspeakable. It is also emblematic of the longing for incarnation, of an unbearable substrate of wanting, of not finding a home in this world or in the next, someone or something that walks the halls of our house or our mind looking for what will help to lay its own self to rest.

What haunts us is always something that seeks its own disappearance: it wants to become fully itself and so depart. If we feel continually haunted, over time we begin to become ghost-like ourselves and roam with intent whilst not quite knowing the object of our intention. Looking in the mirror, our face begins to look like our not-quite-incarnated life. We walk not exactly existing in the world we visit. Like the spirits and half-beings we imitate at Halloween, we roam the streets as if looking for an abode on this earth we are unable to locate, demanding tribute from those who dwell within. The exorcism of an unwanted spirit is consistent the world over: an invitation to return home; for it and for us to find our way back, to cease our restless ways and to quit disturbing others’ lives or walking their houses by night.

We cease to be haunted when we cease to be afraid of making what has been untouchable real and touchable again: especially our understandings of the past, and especially those we wronged, those we were wronged by, or those we did not help. We become real by forgiving ourselves, and we forgive ourselves most authentically by changing the foundational pattern of our behaviour, especially our behaviour to those we have hurt. A fear of ghosts, or a fear of our own haunted mind, is the measure of our absence in this world.

We cease to be afraid when we give away what was never ours in the first place and begin to be present to our own lives just as we find them, in our earthly vulnerabilities, even in facing what we have banished from our thoughts and made homeless, even when we do not know the way forward ourselves. When we make a friend of what we previously could not face, what once haunted us now becomes an invisible, parallel ally, a beckoning hand to our future.

We banish the misaligned when we align with what we are called to; we become visible and real when we give our gift and stop waiting for the gift to be given to us. We wake into our lives again, as if for the first time, laying to rest what previously had no home, through beginning to speak, beginning to make real and beginning to live, those elements constellating inside us that long to move from the invisible to the visible.

-From Consolations: The Solace, Nourishment and Underlying Meaning of Everyday Words: Revised Edition

LikeLiked by 3 people

I really love this description of haunting – it really sets out the parameters of being both real and unreal at the same time – perhaps it was what Dickens’s marriage was to him by this point. I play around with notions of unseen in Dickens’s post-Divorce Act work, and haunting – in all its forms – is definitely part of that.

Meanwhile, I am so pleased I am not the only one that finds the opening to Little Dorrit a little slow – will it have grown on me by the end of the reading, though, I am still not convinced.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Daniel, on your question about the Francis Hopkinson Smith, it is listed as a “painting” (watercolor?)… and in spite of the evocative atmosphere, looks photographic in its detail. It is part of the illustrations added to Smith’s collection of four essays on “Outdoor Sketches”: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/27340/27340-h/27340-h.htm#pic_1 And it appears to be a work of the early 20th century, long past the time of the Marshalsea–which was closed in the 1840s and mostly demolished a few decades later–but this appears to be illustrating the alley near its remaining wall (which still stands). Smith visited London in 1913.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just throwing this out there for discussion, but it is an interesting sort of doubling, that both Rigaud and William Dorrit–both prisoners, as we begin our story–have this fundamental compulsion about making everyone aware without the shadow of a doubt that that they are *gentlemen*.

LikeLiked by 6 people

And for all their bluster they never achieve that status as easily as Arthur does by the simple act of removing his hat when he enters Mrs Plornish’s home in Bleeding Heart Yard. (Bk 1 Ch 12)

LikeLiked by 3 people

I think that’s spot on, Rach and Chris. You could see Rigaud too as destroyed by it, at a stretch (motivated and embittered by it, anyway): by the idea that nothing else matters other than being acknowedged as a gentleman. It’s definitely what destroys Dorrit and what makes him such an agonising character – his own snobbery and his ghastly blindness to everything good that doesn’t meet class criteria. Hence the horror of the mad scene.

I’ve got more to say about this in another comment, coming. I think it’s at the heart of Little Dorrit.

LikeLiked by 1 person

To elaborate that slightly: by “the idea that nothing else matters other than being acknowedged as a gentleman”, I mean the idea that the only source of social worth is class and that actions by someone of the right class are blameless.

LikeLiked by 1 person

OMG Rach: a film reference, and a mighty fine one. Uncle Charley as “Gentleman”…! He’s definitely a prisoner in his own psychopathic world! Rigaud as psychopath?

LikeLike

“I could never have been of any use, if I had not pretended a little.”

(Little Dorrit to Arthur, Bk 1 Ch 14)

There is a skill to family management, perhaps best known to mothers though not exclusive to that designation, that when practiced expertly is invisible and seamless. Little Dorrit took it upon herself to learn and master this skill at an early age, instinctively knowing that someone had to do it or her family would surely perish:

“What her pitiful look saw, at that early time, in her father, in her sister, in her brother, in the jail; how much, or how little of the wretched truth it pleased God to make visible to her; lies hidden with many mysteries. It is enough that she was inspired to be something which was not what the rest were, and to be that something, different and laborious, for the sake of the rest. Inspired? Yes. Shall we speak of the inspiration of a poet or a priest, and not of the heart impelled by love and self-devotion to the lowliest work in the lowliest way of life!” (Bk 1 Ch 7)

She may not be worldly wise, but Amy understands her little piece of the world and manages it with a deft hand. She is alert, forward thinking and savvy, as illustrated by her noticing her sister’s “desire” to learn dancing and cajoling the incarcerated dancing master to teach her, and by securing for herself in a like manner lessons in needlework. That she is unable to secure a career/position for her brother is not for lack of trying. Her greatest challenge and achievement is in the ongoing “pious fraud” she spearheads for her father benefit. On one hand it can be argued that she is enabling him in his delusions, but on the other she has found a way to keep him going, to keep him from the awful and horrific reality of his situation which she knows would be the death of him. Knowing that she must provide for both herself and her father (and to supplement the “testimonials” he receives from other “collegians”), she solicits for and finds needlework for herself via her connection with the Plornish’s outside the prison walls. This gives her a much needed outlet from the claustrophobic atmosphere of the prison – though Mrs Clennam’s house isn’t really much better and Amy basically goes from one prison to another – and introduces her to Arthur from whom she, at last, finds real support and a kindred spirit.

I want to refer you again, with a Spoiler Alert, to Sharon Aronofsky Weltman’s article, “The Littleness of Little Dorrit”, which I posted in my “Supplement to Little Dorrit” post and which discusses Amy much better than I can do here.

As to Arthur, is there a more poignant moment than the ending of Bk 1 Ch 13 “Patriarchal” when Arthur returns to his lodgings after visiting the Casbys and reflects upon his life?

“He was a dreamer in such wise, because he was a man who had, deep-rooted in his nature, a belief in all the gentle and good things his life had been without. Bred in meanness and hard dealing, this had rescued him to be a man of honourable mind and open hand. Bred in coldness and severity, this had rescued him to have a warm and sympathetic heart. Bred in a creed too darkly audacious to pursue, through its process of reserving the making of man in the image of his Creator to the making of his Creator in the image of an erring man, this had rescued him to judge not, and in humility to be merciful, and have hope and charity.

“And this saved him still from the whimpering weakness and cruel selfishness of holding that because such a happiness or such a virtue had not come into his little path, or worked well for him, therefore it was not in the great scheme, but was reducible, when found in appearance, to the basest elements. A disappointed mind he had, but a mind too firm and healthy for such unwholesome air. Leaving himself in the dark, it could rise into the light, seeing it shine on others and hailing it.

“Therefore, he sat before his dying fire, sorrowful to think upon the way by which he had come to that night, yet not strewing poison on the way by which other men had come to it. That he should have missed so much, and at his time of life should look so far about him for any staff to bear him company upon his downward journey and cheer it, was a just regret. He looked at the fire from which the blaze departed, from which the afterglow subsided, in which the ashes turned grey, from which they dropped to dust, and thought, ‘How soon I too shall pass through such changes, and be gone!’

“To review his life was like descending a green tree in fruit and flower, and seeing all the branches wither and drop off, one by one, as he came down towards them.

“‘From the unhappy suppression of my youngest days, through the rigid and unloving home that followed them, through my departure, my long exile, my return, my mother’s welcome, my intercourse with her since, down to the afternoon of this day with poor Flora,’” said Arthur Clennam, “‘what have I found!’”

“His door was softly opened, and these spoken words startled him, and came as if they were an answer:

“‘Little Dorrit.’”

These paragraphs, like the death of Little Paul Dombey (““Mama is like you, Floy. I know her by the face!” (DS, Ch 16)), always makes me cry! The ease with which Dickens takes us, in a few paragraphs, through Arthur’s reflections so that we understand his past and how it formed and affected -or didn’t – his current mindset at 40 years old! On his own for the first time Arthur