Wherein The Dickens Chronological Reading Club wraps up Weeks 5 & 6 of A Tale of Two Cities, our 21st read; with a chapter summary, discussion wrap-up, and a look-ahead to weeks 7 & 8.

(Banner image: “Storming of the Bastille” by Jean-Pierre Houël)

by the members of the #DickensClub, edited/compiled by Rach

Friends, things are looking bleak indeed for Charles Darnay and his family as Charles finds himself “drawn to the Lodestone Rock” to Paris. Through the help of Doctor Manette–who is now showing a new strength and power founded on his old suffering in the Bastille–Darnay is saved from the butchery of the September massacres, only to be still held prisoner for a year and three months before being brought to trial. What will happen next?

Before we get into our summary and discussion, a few quick links:

- General Mems

- A Tale of Two Cities, “Book the Second” Chs 19-24, & “Book the Third” Chs 1-5: A Summary

- Discussion Wrap-Up (Weeks 5-6)

- A Look-Ahead to Weeks 7 & 8 of A Tale of Two Cities (13-26 Feb, 2024)

General Mems

In anticipation of Wednesday, Boze, myself, and Sam Weller would like to wish everyone a Happy “Walentine’s” Day! Are you, like Sam, struggling to write to your friend or significant other? Check out Tony Weller’s advice to his son in Chapter 33 of The Pickwick Papers!

“‘Wot I like in that ‘ere style of writin’,’ said the elder Mr. Weller, ‘is, that there ain’t no callin’ names in it–no Wenuses, nor nothin’ o’ that kind. Wot’s the good o’ callin’ a young ‘ooman a Wenus or a angel, Sammy?'”

SAVE THE DATE: Join us for our upcoming chat on A Tale of Two Cities on Saturday, 2 March, 2024. 11am Pacific/2pm Eastern/7pm GMT (London). Rach will be emailing a Zoom link prior to the meeting; let her know if you’d like to be added to the email list!

If you’re counting, today is Day 770 (and week 111) in our #DickensClub! This week and next, we’ll be finishing A Tale of Two Cities, our twenty-first read as a group. Please feel free to comment below this post for the final chapters (weeks 7 & 8) or use the hashtag #DickensClub if you’re commenting on twitter/X.

No matter where you’re at in the reading process, a huge “thank you” for reading along with us. Heartfelt thanks to our dear Dickens Fellowship, The Dickens Society, and the Charles Dickens Letters Project for retweets, and to all those liking, sharing, and encouraging our Club, including Gina Dalfonzo, Dr. Christian Lehmann and Dr. Pete Orford. Huge “thank you” also to The Circumlocution Office (on twitter also!) for providing such a marvelous online resource for us.

And for any more recent members or for those who might be interested in joining: the revised two-and-a-half year reading schedule can be found here. If you’ve been reading along with us but aren’t yet on the Member List, we would love to add you! Please feel free to message Rach here on the site, or on twitter. And for any more recent members or for those who might be interested in joining: the revised two-and-a-half year reading schedule can be found here. If you’ve been reading along with us but aren’t yet on the Member List, we would love to add you! Please feel free to message Rach here on the site, or on twitter.

For Rach & Boze’s Introduction to A Tale of Two Cities, please click here. For Chris’s wonderful supplemental materials to ATTC, please click here.

A Tale of Two Cities, “Book the Second” Chs 19-24, & “Book the Third” Chs 1-5: A Summary

(Illustrated by Phiz. Images below are from the Charles Dickens Illustrated Gallery.)

By the tenth day after Lucie and Charles Darnay’s departure for their honeymoon, Mr Lorry wakes from his watch by Dr Manette to find that his troubled friend appears to be calm and clear-headed again, and his old work put aside. With delicacy, Mr Lorry discusses the situation with Doctor Manette, curious as to what might have caused such a reversion. Manette believes that only a very specific set of circumstances–we intuit here that he refers to Charles Darnay’s private discussion with Manette on the former’s wedding morning–could have set it in motion, and he believes only a very particular strain in that quarter again could revive it, which he believes is unlikely to occur. Lorry gently persuades the Doctor to allow him to get rid of his old tools and workbench, and not to keep close such reminders of his old confinement. Reluctantly, Manette agrees—only asking that it be done when he is not around to see it.

“Mr Lorry went into his room with a chopper, saw, chisel, and hammer, attended by Miss Pross carrying a light. There, with closed doors, and in a mysterious and guilty manner, Mr Lorry hacked the shoemaker’s bench to pieces, while Miss Pross held the candle as if she were assisting at a murder…”

Meanwhile, upon the return of Lucie and her husband, “the first person who appeared, to offer his congratulations, was Sydney Carton.” Carton, in his odd way, apologizes to Darnay for being “insufferable” on a certain occasion after they first met at the trial. More than that, he asks Darnay if he might, however rarely, come and go at their new home “at odd times” like a useless piece of furniture “tolerated for its old service and taken no notice of.” Darnay agrees. Later, however, after Carton leaves, Darnay speaks of him as “a problem of carelessness and recklessness.” In private, Lucie asks her husband “to be very generous with [Carton] always, and very lenient on his faults when he is not by. I would ask you to believe that he has a heart he very, very, seldom reveals, and that there are deep wounds in it.” Darnay promises to keep this in mind.

Years pass. And in “the echoing footsteps of years,” Lucie and Charles have first a daughter, “little Lucie,” and then a son. The boy died, not without a final wish for “Poor Carton! Kiss him for me!”

“…little Lucie, comically studious at the task of the morning, or dressing a doll at her mother’s footstool, chattered in the tongues of the Two Cities that were blended in her life.”

Meanwhile, “Mr Stryver shouldered his way through the law, like some great engine forcing itself through turbid water, and dragged his useful friend in his wake, like a boat towed astern.” Stryver, who had since married “a florid widow,” offers, rather comically-offensively, a kind of patronage to Darnay in the form of Stryver’s three children whom he wishes Darnay to tutor. Darnay refuses.

“But, there were other echoes, from a distance, that rumbled menacingly…and it was now, about little Lucie’s sixth birthday, that they began to have an awful sound, as of a great storm in France with a dreadful sea rising.”

It is mid-July, 1789. Madame Defarge leads the women who are marching to the Bastille prison, while her husband leads the mob who storm the Bastille and overcome the “massive stone walls” and “the eight great towers.” They are determined to free the prisoners and find their needed weapons which they believe are being held within the fortress, and Madame Defarge brutally finishes off—“with her cruel knife”—the life of the governor of the Bastille. Her husband forces a guard to show him One Hundred and Five, North Tower. After finding Manette’s initials carved into the stone, he searches the cell. They take vengeance on one of those (“old Foulon”) who was suspected of plots against the people and to contributing to food shortages. Some of the furious people, including the “mender of roads” who blows with any wind, then burn the chateau of the Marquis St Evrémonde. Monsieur Gabelle, the steward left in charge by the nephew who had disowned the property, managed to survive.

But Gabelle, who had tried to help the people as instructed, was captured and imprisoned. He sent a nearly hopeless letter abroad, trying to communicate with the new marquis–who we know as Charles Darnay–by way of Tellson’s Bank, as they are both an English and a French house. Thus, when Darnay is speaking to Lorry—the latter is about to leave for Paris to try and clear up the mess of documents and other precious things that are in danger due to the turmoil of the city—Lorry discusses this mysterious letter and the unknown Marquis St Evrémonde. Charles says that he will take it to the marquis, as he is known to him.

The letter pleads to the current marquis to come and testify for him, Gabelle, who otherwise will lose his life because he “has acted against [the people] for an emigrant.” After some soul-searching, Darnay decides to go to Paris, to aid this faithful servant who had done no wrong, and who was imprisoned because of Gabelle’s fidelity to Darnay and the house. Darnay leaves for Paris shortly after Lorry, but secretly. He leaves behind a letter to inform his wife and the Doctor, who will not see it until after he is gone.

But as our final book, Book the Third, begins, Darnay finds Paris to be even more dangerous to himself than he could have imagined. Laws were just passed against emigrants, including a decree for the sale of property of emigrants. Darnay is taken into custody—and not only imprisoned, but alone, “in secret.” Even Monsieur Defarge, old servant to Dr Manette, refuses to help the Doctor’s son-in-law, for some mysterious reason of his own. Darnay is haunted by thoughts of his father-in-law’s imprisonment.

Mr Lorry, at the Paris branch of Tellson’s Bank, is unaware that Darnay had even come to France, until he is startled to see Lucie, her father, her daughter, and Miss Pross enter the scene, having followed Darnay with some inkling of the danger that he is involved in. Lorry is equally terrified to hear this news. Only Doctor Manette, whose position as one who had been “buried” in the Bastille for eighteen years has given him a kind of power and influence with the people, keeps calm in the midst of it all. Lorry begs Lucie to withdraw and not to look out at some of the chaos in the streets. For they have arrived during the dreadful September massacres, when the people forced their way into Paris prisons and murdered many of their inmates, suspicious of traitors and foreign plots. Once Lucie has withdrawn, Lorry explains the danger to Manette, and begs Manette, if he truly has power with the people, to get them to take Manette to the prison where Darnay is being held, to save him from the massacre. He does so, and Manette is helped by the populace.

Monsieur and Madame Defarge reintroduce themselves to Lorry and Lucie, implying that they wish to have a good look at Lucie and her child, so as to save them if they should be endangered by the populace. But Lucie feels a terror and utter lack of pity in the glare of Madame Defarge, whose shadow seems to fall upon her and her daughter.

“‘Is that his child?’ said Madame Defarge, stopping in her work for the first time, and pointing her knitting-needle at little Lucie as if it were the finger of Fate.”

The Doctor was away for several days, ensuring that Charles, though imprisoned, was saved from the murderous intent of the people, “who had taken [Darnay] through a scene of carnage to the prison of La Force.” An informal tribunal decided that Darnay, though still to be held in custody, would be in safe custody. Doctor Manette is confident that he will be able to save Charles, and to free him. As the months pass, the Doctor, who is allowed to visit Charles, works tirelessly to get his case brought to trial.

“For the first time the Doctor felt, now, that his suffering was strength and power…the Doctor walked among the terrors with a stead head. No man better known than he, in Paris at that day; no man in a stranger situation. Silent, humane, indispensable in hospital and prison, using his art equally among assassins and victims, he was a man apart….He was not suspected or brought in question, any more than if he had indeed been recalled to life some eighteen years before, or were a Spirit moving among mortals.”

Altogether, a year and three months pass. We are now in December of 1793. Lucie, faithfully attending to her duties while never sure whether her husband would survive another day, waits each day for several hours at a certain place near the prison, where, by chance, her husband might, on a lucky day, be able to glimpse her from a window. She often goes with her child. Both of them are observed by the wood-sawyer, formerly the mender of roads, who appears to be giddy with the violence, and jokes with them in a threatening-suspicious manner. At last, Lucie hears the news from her father that Charles has been “removed to the Conciergerie” and summoned for trial on the next day.

Discussion Wrap-Up (Weeks 5-6)

Miscellany; What We Loved

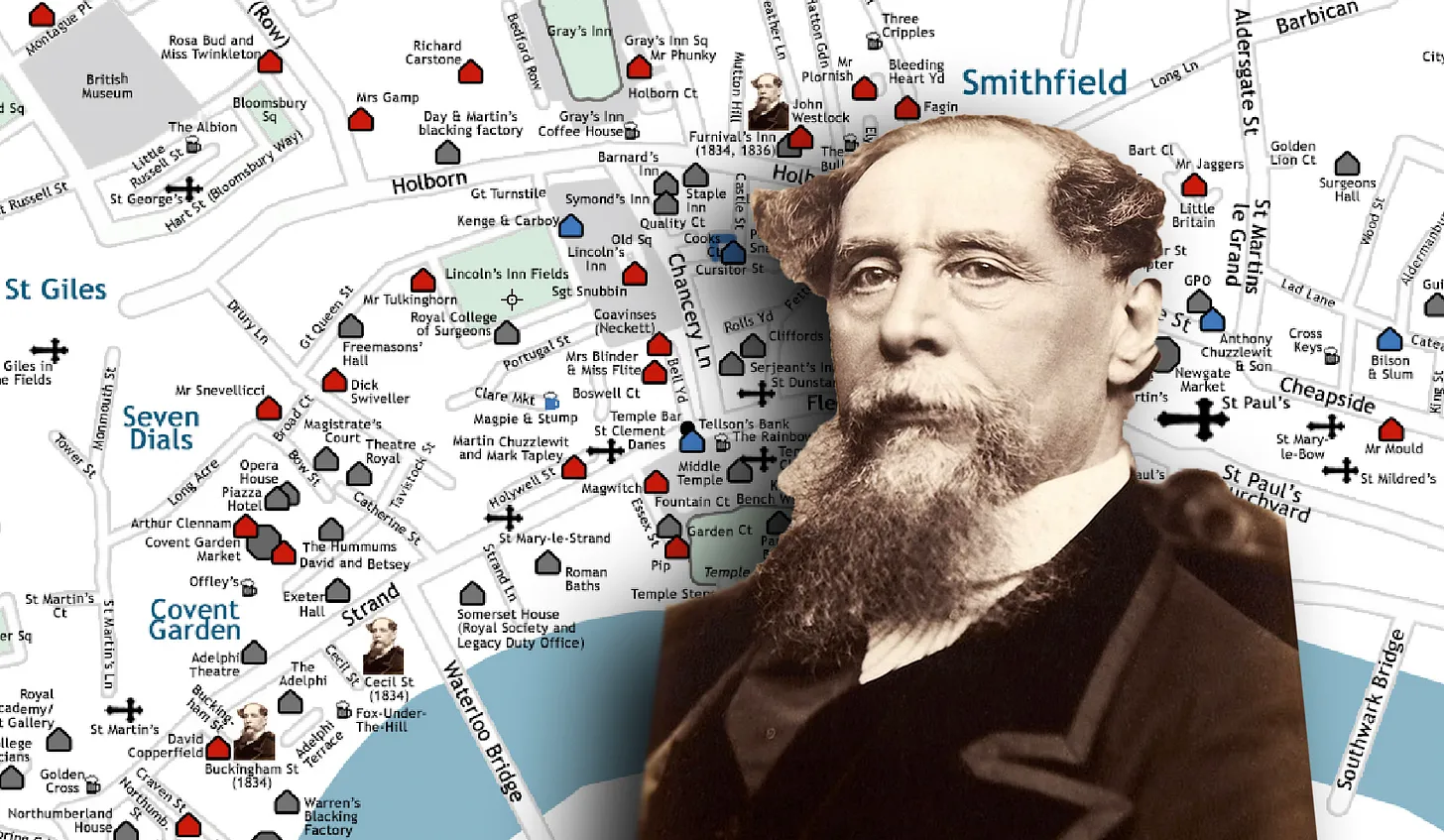

Lucy drew our attention to this marvelous, searchable map with all of Dickens’s London locations!

She also shared with us some background material on this wonderful project!

Here, the Stationmaster shares some of the things he loves about our current sections:

He also appreciates how “the book’s quality really picks up with outbreak of the Revolution. Not that the writing was bad or anything prior to it! It was technically great, but it struck me as kind of aloof for Dickens and it wasn’t really stirring my emotions.”

Dickens as “The Haunted Man”

In keeping with our ongoing theme of “Dickens as ‘The Haunted Man,'” Deborah has been pondering the timing and setting of this piece, in relation to his life at the time, and the separation with Catherine:

Character Spotlight: Sydney Carton

Daniel commented on several things that he especially appreciated about the wrap-up from Weeks 3 & 4, and noted these things in regard to Sydney Carton:

Charles Darnay and “Monseigneur”

Here, Chris tackles the question of what Darnay really did, or didn’t do, to redress the wrongs of his ancestors. Was he as responsible as he should have been with his disowned inheritance? Might things have turned out differently had he fully disposed of the property before abandoning it?

Doctor Manette & Solitary Confinement

And just as the Stationmaster commented on how much he loves to see the Doctor come into his own during this section, with his old suffering being a “strength” and a “power,” Daniel comments on the powerful depiction of solitary confinement:

Comparing A Tale of Two Cities with Barnaby Rudge

Chris has really been bringing to light the many similarities in tone and theme between A Tale of Two Cities and Barnaby Rudge. Here, she gives a lot of specific detail. Can we think of other parallels?

Character Spotlight: the Defarges

Daniel appreciated the discussion of Madame Defarge during Weeks 3 & 4:

Are the Defarges “the Dickensian villains with the healthiest marriage since Mr. and Mrs. Squeers”? The Stationmaster comments:

A Look-Ahead to Weeks 7 & 8 of A Tale of Two Cities (13-26 Feb, 2024)

For our final two weeks with A Tale of Two Cities, we’ll be completing “Book the Third,” Chapters 6-15. Our portions during Weeks 7 & 8 were published in weekly parts in the periodical All the Year Round between 8 Oct and 26 Nov, 1859.

Please comment below for any insights during our final two weeks, or use the hashtag #DickensClub if commenting on twitter/X.

If you’d like to read it online, you can find it at a number of sites such The Circumlocution Office; you can download it from sites such as Gutenberg.

I just really wanted to thank everyone for such insightful comments!!! I got behind in commenting myself during these last two weeks, as I have just started a new job; this is my third week. (I knew it was coming, the need to relegate the full-time sewing work to a more part time “side hustle,” but didn’t know exactly when/how it would come about! 😉 )

I’m so eager to hear everyone’s thoughts about the final section! Especially for those who don’t know or remember the ending. Stationmaster, I laughed out loud about your comment re: the Defarges having the healthiest villain-marriage since the Squeers! 😉 That was amazing.

Daniel & Lucy, I just love the insights and resources you shared, re: solitary confinement, Madame Defarge, etc. That map…what a treasure!

Chris, I feel like there could be a whole post on the comparisons between BR & ATTC!!! I can’t “unsee” the idea of all of these characters bumping into each other on the streets.

And I know that Deborah is working through some things about ATTC related to Dickens’s life that I’m really intrigued by.

I’ll see if I can pull together that special interest post on “Time & Memory” during these final weeks–or, at latest, during the break. I’ll try, anyhow! 🙂

Hope everyone has a marvelous week!

LikeLiked by 5 people

I finished the book! Nobody read my comments until they’ve done so.

How do you think Dickens want us to view Miss Pross’s anti-gallic sentiments? Should we simply cheer for her? Or see her from a realistic perspective as bigoted?

Lucie turns out to be right to still fear for her husband’s life after his initial and her father comes across as almost smug and condescending in his confidence that he’s saved the day. Did Dickens want us to actually feel some satisfaction in seeing him proved wrong? I almost get the feeling that he did in Chapter 7 but not at all in Chapter 10.

I love Sydney Carton’s melancholy walks through the streets of Paris.

In the brief glimpse we get of her, Charles Darnay’s mother becomes a really intriguing and haunting character. It occurs to me that Darnay is similar to Esther Summerson of Bleak House in that both live in fear of being punished for their parents’ misdeeds.

Dr. Manette and Mme. Defarge are kind of foils to each other. Both were victimized by the Evremondes but Dr. Manette is able to set aside his grudge against them and see the goodness in some members of the family, even to point of letting his daughter marry one. Madame not so much.

I love Sydney Carton’s conversations with Mr. Lorry in Chapters 11 and 12 in which the former’s words have meanings that we know (or suspect anyway) but the latter doesn’t. Shakespeare was great at writing conversations like that.

It’s interesting that Madame Defarge ponders if there’s a way she can implicate Lucie without implicating Dr. Manette for her husband’s sake though she quickly rejects the idea. A little touch of virtue in her before she dies.

Now that I’ve read both books all the way through, I think I still prefer Barnaby Rudge to A Tale of Two Cities. I know that opinion is very much a minority one. Many consider Two Cities one of Dickens’s best books and Barnaby the bottom of the Dickensian barrel. I really do consider A Tale of Two Cities a gripping read but I feel like Barnaby Rudge’s cast of characters are more memorable for me. I also love how Dickens shows all the different types of people who get involved in a revolution in that book. You’ve got those who, whatever their faults, aren’t naturally bloodthirsty and really believe in the revolution’s ideals like Mrs. Varden. You’ve got those like Hugh Maypole who have real grievances against society. You’ve got those like Simon Tappertit who are just entitled. Those who just use the revolution as a means to grab power like Gashford and those like Ned Dennis who just want to an excuse for violence. In A Tale of Two Cities, except for the Defarges who are highly memorable, all the French revolutionaries tend to blend together. They don’t have much in the way of individual personalities. I understand that was part of Dickens’s point about mob mentality, but I prefer Barnaby Rudge’s more nuanced and detailed look at the insurrection. Maybe since Dickens was closer (geographically) to the Gordon Riots than the September Massacres or the storming of the Bastille, he could depict them better.

That’s not to say his depiction of the French Revolution is bad per se. In fact, it’s great. And I’ll readily conceded that A Tale of Two Cities probably has the more striking ending than that of Barnaby Rudge. Looking at the plots from a distance, I’d say Dickens’s later historical novel about mob violence has the better story. But when I actually read them, I’m more a fan of the earlier one.

I’ve described Bleak House, Hard Times and Little Dorrit as representing a “period” of Dickens, a dark one. I see A Tale of Two Cities as the dawn of new period for Dickens. It’s hard for me to explain why. It’s not like A Tale of Two Cities lacks dark material. (Neither do Great Expectations or Our Mutual Friend.) But somehow its tone doesn’t feel bleak or bitter to me the way Dickens’s previous three books do. Maybe it has to do with something one of the writers wrote in one of the introductions Chris shared in supplements to A Tale of Two Cities. (I believe it was G. K. Chesterton.) With this book, you get the feeling that every tragedy is taking place in the daylight. (Well, I picture the tragedies that we hear befall the Defarge family in Chapter 10 happening at night as Dickens describes but that’s it.)

More thoughts later.

LikeLiked by 3 people

The following is an excerpt from Gillen D’Arcy Wood’s introduction to A Tale of Two Cities. I found it so interesting that I had to share it.

As a novelist, Dickens, who loved Paris and traveled there often, offered more intuitive, closely observed reasons for the untranslatable quality of that city’s revolution. In an 1856 article for his weekly magazine, Household Words, he calls Paris “the Moon” and describes a culture of spectacle implicitly alien to his London readers. On the grand Parisian boulevards, Dickens watches the upper classes put on “a mighty show.” Later, he takes coffee and a cigar at one of Paris’s ubiquitous cafes and participates in a kind of collective voyeurism unfamiliar to the English capital:

“The place from which the shop has been taken makes a gay proscenium; as I sit and smoke, the street becomes a stage with an endless procession of lively actors crossing and recrossing. Women with children, carts and coaches, men on horseback, soldiers, watercarriers with their pails, family groups, more soldiers, lounging exquisites, more family groups, (coming past, flushed, a little late for the play) …We are all amused, sitting seeing the traffic in the street and the traffic in the street is in its turn amused by seeing us.”

Paris is a society of spectacle, a glamorous outdoor “stage” where citizens may be both actors and audience. Later in the article however, Dickens describes a more sinister aspect of this culture of display when he is jostled by the crowds at the Paris morgue “whose bodies lie on inclined planes within a great glass window as Holbein should represent Death in his grim dance keeping a shop and displaying his good like a Regent Street or boulevard linen draper.” Dickens was unnerved here, as he was at Horsemonger Lane, on a society that places no restrains on visibility, even to preserve the solemnity of the dead.

It is a short step in Dickens’s imagination to from the peepshow atmosphere of the Paris morgue in 1956 to the ritual slaughter in the Place de la Revolution during Robespierre’s “Reign of Terror” of 1793-1794. A Tale of Two Cities shows the dark side of urban theatricality, that a public appetite for glamorous “show” can rapidly degenerate into an insatiable hunger for “scenes of horror and demoralization.” The essentially theatrical quality of theatrical life produces a theatrical Revolution. At the revolutionary “trials” at the Hall of Examination, Madame Defarge, we are told, “clapped her hands as at a play.” There is something uniquely Parisian too in the spectacle of the liberation of the Bastille (with only seven prisoners inside) and the rituals of the Terror itself, as the tumbrils roll daily to the guillotine watched by knitting ladies, who take up seats in their favored spots each morning as if at a sideshow or circus. As Dickens describes it, even the victims of the Terror cannot escape the theatrical atmosphere of the proceedings. Among the condemned, “there are some so heedful of their looks that they cast upon the multitude such glances as they have seen in theatres and in pictures.” Contrast this with Charles Darnay who, on trial for his life earlier in the novel, disdains “the play at the Old Bailey.” He “neither flinched from the situation nor assumed any theatrical air in it.” Our hero disappoints us on occasion but here, by resisting being converted into a spectacle, he defends the most important social principle of the novel: the dignity of the private citizen in the face of the howling mob.

Theatricality is not the monopoly of the Terror. As the scene of the royal procession at Versailles shows, public exhibition was a deep grained aspect of French court culture that, when revolution came, translated easily in the imagination from the palace to the public square:

“Soon the large-faced king and the fair-faced queen came in their golden coach, attended by the shining bull’s eye of their court, a glittering multitude of laughing ladies and fine lords; and in jewels and silks and powder and splendor and elegantly spurning figures and handsomely disdainful faces of both sexes, the mender of roads bathed himself , so much to his temporary intoxication, that he cried Long live the King, Long live the Queen, Long live everybody and everything…until he absolutely wept with sentiment.”

…The grotesque pomp and negligence of the royals that Dickens describes might itself have represented sufficient justification for revolution were it not for the mindless response of “the mender of roads,” a hapless would-be revolutionary who shows himself so susceptible to the glamor of court spectacle that he weeps and wishes long life to those very people he has sworn to destroy. The dangers of a society of spectacle are summed up in his response: Whether it is the court of Louis XVI or Robespierre’s revolutionary committee, no government that asserts its power in the form of public exhibition can guarantee control of its audience’s reaction. The irrational fervor inspired by spectacle may distract the people from ideology, as it does the mender of roads at Versailles, who is disarmed by “sentiment”, but spectacle may just as easily produce the murderous revolutionary dance of the carmagnole, and the tumbrils that bring everyone-Louis and Robespierre, royals and revolutionaries alike-before the indiscriminate justice of the guillotine.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Boy, the “culture of the spectacle really rings true here in this novel. And also the notion of the “peepshow,” especially as it applies to the morgue–where bodies are on display as though they were goods being shown in a shop window. I’m wondering what this kind of morbid observation and fascination does to the group psyche as it pertains to its ideas about death and destruction. The women furiously knitting at the guillotine while watching the giant knife cut through human flesh and the resulting decapitation. As I think about this horrifying spectacle, I reflect back on “The Heart of Darkness” and the horror of it all, where the heads are being displayed on the tops of stakes surrounding the Kurtz compound. Are we witnessing the ultimate of human degradation, here? Fast forward to the Nazi “spectacles” and the present Trump rallies which are choreographed to touch and excite the darkest shadow sides of our collective psyches–where, sadly, the reverence for human life and its marvelous capabilities become nil and void.

Might we then rename the third act of ATOTC as “The Heart of Darkness with a minor reprieve.” Charles lives but the destruction in Paris lives on.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What should we think of Gabelle who is responsible for Darnay’s plight? We can’t blame him for begging for help, but I couldn’t help but notice that once he’s free, he doesn’t do anything to help Darnay.

After Dickens Club is over, I’m planning on doing a movie marathon of all the best black and white movies based on Dickens books, one adaptation per book. (Why black and white ones specifically? Just a whim.) Which one do people recommend I do for A Tale of Two Cities, the 1935 one or the 1958? For those curious, here’s my list so far. (I’ll be watching them in the order the original stories were published, not the order the movies themselves were released.)

The Pickwick Papers (1952)

Oliver Twist (1948)

Nicholas Nickleby (1947)

Scrooge (1951)

David Copperfield (1936)

Great Expectations (1946)

It’d be nice if I did the 1936 Tale of Two Cities so the 1936 David Copperfield wouldn’t be the only part of the marathon from that decade. But maybe the 1958 movie is really better.

Some of you may remember from Dickens Club’s first zoom meeting that I was introduced to Charles Dickens as a kid largely through the television show, Wishbone, which is about…well, it’s better if you google it. If tried to explain it in a comment, it’d sound like I was hallucinating. Anyway, they did an episode that adapted A Tale of Two Cities and there was also a tie-in novel version of it. I remember a line original to that tie-in, something Sydney Carton says to the condemned seamstress he befriends. (She’s one of my favorite bit characters in Dickens BTW.) It’s in response to her saying she doesn’t understand how her death will help the revolution.

“I’ve always believed a revolution itself dies the moment it harms one of the people it was supposed to help.”

I was actually a little surprised a version of the line wasn’t in the book. I mean, I wasn’t very surprised because it doesn’t have the rhythm of the book’s dialogue. But it’s a lot more haunting than something I’d expect from a tie-in novel to a children’s television show. Props to Joanne Barkan who wrote it.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I agree, Stationmaster: it’s an extraordinary statement which contains extraordinary meanings. And what an exquisite memory you have! Gads, that you should be so impacted by this as a child; oh my!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, I couldn’t remember the exact words. I had to find the book and check them. LOL.

LikeLike

I suspect Gabelle was compelled to write his letter – perhaps by the Defarges – to entice Darnay to return. I also suspect Gabelle kept quiet when Darnay did return – again perhaps compelled by the Defarges – to protect his own neck.

LikeLiked by 2 people

The 1935 film is much more popular and more accessible, but I prefer the 1958, mainly because I think — as much as I like Colman — Bogarde’s portrayal of Carton is superior to Colman’s (and Tutin’s portrayal of Lucie is VASTLY superior to Allan’s).

LikeLiked by 2 people

I watched the 1935 movie the other day and I thought it was awesome. (Possibly better than the book in some-I repeat some, not all-ways.) But since you prefer the 1958, I’ll check that one out too and it’s likely as not I’ll agree with you and do that one for my eventual movie marathon. Thanks for the tip.

LikeLike

Agreed on both counts, Gina!!!

LikeLike

I too have finished the book, and even though I knew how it ended, having read it before, the tears still came, unbidden, to my broken heart. It is just such a perfect ending for the book, and I think I understand this now more than what I ever did previously.

One of the things that struck me as I was reading this time is the parallels between Madame Defarge and Miss Pross, and what an interesting exercise it would be to compare their journeys, particularly their individual responses to trauma and betrayal. Dickens had such a skill in giving such depth and nuance to the supporting characters that it becomes quite frustrating when he doesn’t (I’m particularly thinking about The Adaptation Stationmaster’s comments regarding Gabelle above).

Dickens, unsurprisingly given his long engagement with the law and law reform, points to what is driving the Revolution: ‘There could have been no such Revolution, if all laws, forms, and ceremonies, had not first been so monstrously abused…’ It is an interesting observation, written at a time when England had gone through a significant period of legal reform, with, for example the Limited Liability Act 1855 and the Joint Stock Companies Act 1856 taken together forming the foundation of modern UK company law first codified pursuant to the Companies Act 1862; with prisoner transportation brought to an end pursuant to the Penal Servitude Act 1853; and compulsory policing introduced throughout England and Wales pursuant to the County and Borough Police Act 1856. Yet while the law of divorce was reformed, there was no real effective change – especially for Dickens, still married to a wife he no longer loved or lived with.

I also particularly enjoyed his description of Darnay as being ‘absolutely Dead in Law.’ The capital letters really emphasise his point. And when he has Doctor Manette comment that there is ‘prodigious strength in sorrow and despair’ it resonates so strongly, in part because of the mastery of the storytelling, but also because you know that the storyteller feels that pain too.

I was in awe of the closing of the circle in the last chapter, with the beginning using the motif of the spilled wine he had so gloriously depicted at the opening of the scenes in Paris closing off the book, with the ‘day’s wine’ being carried to the guillotine. It represents such brilliance in the writing, and suggests how much Dickens must have carried his story in his head as he wrote it, a testament, if one was even needed, to the incomparable genius of the man.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Doborah: what a brilliant statement–“I was in awe of the closing of the circle….” Gosh, there is so much here, it’s difficult to know where to begin, but my thought is more theological in that the wine as symbol prevails. The cask-breaking episode/chapter is rife with meanings and the one that strikes me the most is its display as a kind of perverse “communion.” I’m not even sure that Dickens needs to have the individual write

“Blood” on the wall for us to see the weirdly religious significance of the people bending down to suck, lick or otherwise devour the blood/wine that has spilled. For me, the dabbing at the blood with the handkerchief and then eating, drinking the wine off the ends of the fabric/wafer cements the notion of Eucharist. As such, this whole scene becomes more than an illustration of people who are literally starving to death (mortally) but who are famished “spiritually.” Thus, then, as you say that the novel with its wine/blood motif comes full circle, there is surely a representation of some bizarre statement about sacrilege–as the folks drinking the wine are merely becoming intoxicated while witnessing the various heads toppling from the vengence of the guillotine. No Christian martyrdom here. Just outright drunken mass murder!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, Lenny!!! SO much to ponder, here!

LikeLike

Wow, Deborah, so beautifully put…I too was struck by that line, and how everything…even seemingly quiet words/motifs, come full circle at the end. It breaks my heart every time, dozens of times later.

LikeLike

I’m looking forward to digesting all of the above – so much brilliance to take in!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sydney plays his cards with Barsad very skillfully, but the trump card is played by Jerry Cruncher who knows via his “honest trade” that Roger Cly is not dead. (Bk 3 Ch 8) Jerry’s “trade” mirrors the “recalled to life” theme. While being a resurrection man is an unsavory trade, its one redeeming quality is that it provided medical men with cadavers for study which led to medical knowledge and breakthroughs in science which, in turn, led to better medical treatment. But these scientific considerations are far from Jerry’s perspective, which sees simply the avariciousness of the medical doctors, undertakers, parish clerks, sextons, and private watchmen, so why not him as well – as he explains to Mr Lorry “There’d be two sides to it. . . . For you cannot sarse the goose and not the gander.” (Bk 3 Ch 9) And if Jerry does take into consideration the unseemliness or illegality of his trade it is only in response to his wife’s “floppin’” which forces him to admit the truth. Yet Jerry finds religion through his experience in Paris where the desecration of the dead is taken to an unfathomable extreme. Similar to Monseigneur, Jerry sees the Devil in his trade and “no sooner beheld him in his terrors then he took to his [not so] noble heels” (Bk 2 Ch 24): “A man don’t see all this ere a goin’ on dreadful round him, in the way of Subjects without heads, dear me, plentiful enough fur to bring the price down to porterage and hardly that, without having’ his serious thought of things.” (Bk 3 Dh 9) His “opinions respectin’ flopping has undergone a change”, and one does not doubt the sincerity of his prayer that he, Miss Pross, and the Manettes get out of France safely. (Bk 3 Ch 14)

Which leads me to wonder how little nine-year-old Lucie’s experience in France will affect her in later life. How can she/will she process the wood-sawyer’s comments:

“‘My work is my business. See my saw! I call it my Little Guillotine. La, la, la; La, la, la! And off his head comes!’

“The billet fell as he spoke, and he threw it into a basket.

“‘I call myself the Samson of the firewood guillotine. See here again! Loo, loo, loo; Loo, loo, loo! And off HER head comes! Now, a child. Tickle, tickle; Pickle, pickle! And off ITS head comes. All the family!’” (Bk 3, Ch 5)

And how can she/will she process the experience of fleeing the city in a cramped carriage with her faux-composed but frantic mother and insensible father, and being required to kiss the “good Republican” guard while “the country-people hanging about, press nearer to the coach doors and greedily stare in; a little child, carried by its mother, has its short arm held out for it, that it may touch the wife of an aristocrat who has gone to the Guillotine”? (Bk 3 Ch 13)

We are given to perceive little Lucie as a pretty sharp little girl. Recall this regarding Sydney: “No man ever really loved a woman, lost her, and knew her with a blameless though an unchanged mind, when she was a wife and a mother, but her children had a strange sympathy with him—an instinctive delicacy of pity for him. What fine hidden sensibilities are touched in such a case, no echoes tell; but it is so, and it was so here. Carton was the first stranger to whom little Lucie held out her chubby arms, and he kept his place with her as she grew.” (Bk B2 Ch 21). It is not surprising then that she should sense something of what is in Sydney’s mind after her father’s death sentence has been confirmed – “‘Oh, Carton, Carton, dear Carton!’ cried little Lucie, springing up and throwing her arms passionately round him, in a burst of grief. ‘Now that you have come, I think you will do something to help mamma, something to save papa! O, look at her, dear Carton! Can you, of all the people who love her, bear to see her so?’” (Bk 3 Ch 11)

Perhaps as the only one to hear Sydney’s parting words to the her mother – “A life you love” – little Lucie is able to understand the broader implications of his sacrifice and thus is able in later life to cope with her experiences. For Sydney does not sacrifice himself simply FOR LUCIE but rather for the LIFE Lucie loves. Remember his words to her in Bk 2 Ch 14: “For you, AND FOR ANY DEAR TO YOU, I would do anything. If my career were of that better kind that there was any opportunity or capacity of sacrifice in it, I would embrace any sacrifice for you AND FOR THOSE DEAR TO YOU. Try to hold me in your mind, at some quiet times, as ardent and sincere in this one thing. The time will come, the time will not be long in coming, when new ties will be formed about you—ties that will bind you yet more tenderly and strongly to the home you so adorn—the dearest ties that will ever grace and gladden you. O Miss Manette, when the little picture of a happy father’s face looks up in yours, when you see your own bright beauty springing up anew at your feet, think now and then that there is a man who would give his life, to keep A LIFE YOU LOVE beside you!” (Emphasis added)

Sydney dies not purely for Lucie, but for the family unit of which Lucie is the heart – it is the ideal family unit, the epitome of family, that MUST be preserved. The family unit that Madame Defarge lost, that Darnay lost, that Dr Manette lost, that Miss Pross lost, that Sydney himself lost – one could say, that France lost.

[An aside — Ironically, it is at this point in time that Dickens has destroyed HIS OWN family unit, while extolling the virtues of Sydney Carton and Richard Wardour (of “The Frozen Deep”) and arguably identifying HIS sacrifice for the woman he loved as somehow equal to theirs.]

This preservation of life with a life counters and conquers Madame Defarge’s strategy of taking life for a life. Her lust for vengeance and extermination blinds her to the true meaning of the “Republic One and Indivisible, Liberty, Equality, Fraternity or Death”. As a high ranking revolutionary she is courted and feared by those she should lead, she manipulates them through their loyalty, she has no pity or compassion, and she uses her position to advance her own agenda. In the end, Madame Defarge is no better than Monsieur the Marquis.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Such a beautifully written commentary, Chris. It covers many of the “perspectives” available to the reader while trying to come to terms with this dark novel and its reflections on one of the darkest moments of French History. You present so well the various human and inhuman visions that contrast so vividly in this narrative–Little Lucie with the Sawyer, Madame Defarge with Sydney, Jerry with Miss Pross, etc. Again I think this kind of contrast/use of characters as foils gets at one the key points–the differentiation of people as valuable and precious souls who matter as opposed to people as commodities or subjects of cynical revenge. Life as treasure versus life as nonentity, life as cheap and meaningless versus life as meaningful. The sadists and lifetakers (Madame Defarge, the Sawyer) stand in such sharp contrast to Little Lucie and Carton who represent “life affirmative.”

In Jungian terms perhaps we could codify these blatant contrasts as dark, negative shadow challenging the positive, feeling anima on both a personal level as well as a nation-wide level. In essence, we are seeing a double psycho drama on both levels–the personal and the universal. Personal psyche (Carton’s, Madame Defarge’s) and collective destructive shadow psyche of France during the Revolution.

To go a bit further, your writing gets at the deep psychological threads that work their way through the novel. So much so, in fact, that I’d be willing to call this narrative MORE than a historical representation of the horrors of the French Revolution and the ways it affected the “common” citizens of France and England, but a deep psychological study of character and motivation. To me, the focus, ultimately, is on the psyches of Sydney, Dr. Manette, and Madame Defarge. They are the movers and the shakers in this novel and become the receptors of the author’s analysis. Each of these characters’ “interior spaces” are examined again and again as their behavior fluctuates throughout the novel. Madame Defarge’s lust for revenge grows steadily as the novel progresses; Sydney leaves behind his cynical, non-caring, analytical side and becomes an entirely different character, especially as you have rendered so well his feeling and caring sides in the conversations above; and Dr. Manette oscillates back and forth from confident mediator to depressed and solitary escapist. Yes, the novel presents so effectively the furor and destructiveness of crowd psychology, the horrors of the guillotine, etc., but I believe its paramount interest is on the psychology of its main characters.

Psychology, psychology, psychology. It’s a psychological novel.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Sydney’s night walk (Bk 3 Ch 9) reminded me of Bill Sikes’s walk after he murdered Nancy. Though their sleeplessness stems from completely opposite motivations (Sydney from altruism, Bill from pure guilt), their senses are working in overdrive, heightening everything they see and hear, taking it all in for the last time.

*

Two instances of ambiguity that augment the theme of doubling:

Sydney’s reason for encouraging Dr Manette to try once more to save Darnay – “I encouraged Doctor Manette in this idea because I felt that it might one day be consolatory to her. Otherwise, she might think ‘his life was wantonly thrown away or wasted,’ and that might trouble her. . . . He will perish; there is no real hope” (Bk 3 Ch 11) – appears to refer to Darnay’s life, but I think, in Sydney’s mind, he is referring to himself. He wants Lucie to understand that his sacrifice was the very last resort after all other avenues to save Darnay had been exhausted.

AND

Darnay’s state of mind on his apparent last day (Bk 3 ch 13) seems to also describe Sydney’s:

“Nevertheless, it was not easy, with the face of his beloved wife fresh before him, to compose his mind to what it must bear. His hold on life was strong, and it was very, very hard to loosen; by gradual efforts and degrees unclosed a little here, it clenched the tighter there; and when he brought his strength to bear on that hand and it yielded, this was closed again. There was a hurry, too, in all his thoughts, a turbulent and heated working of his heart, that contended against resignation. If, for a moment, he did feel resigned, then his wife and child who had to live after him, seemed to protest and to make it a selfish thing.

“But, all this was at first. Before long, the consideration that there was no disgrace in the fate he must meet, and that numbers went the same road wrongfully, and trod it firmly every day, sprang up to stimulate him. Next followed the thought that much of the future peace of mind enjoyable by the dear ones, depended on his quiet fortitude. So, by degrees he calmed into the better state, when he could raise his thoughts much higher, and draw comfort down.”

LikeLiked by 3 people

More interior views, more psychological examination. Thanks again for pointing all of this out to us, Chris!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’d like to recommend fans of A Tale of Two Cities check out the book, The Prisoners of September by Leon Garfield. It also takes place in England and France and around the same time period too. Garfield deserves to be far better known than he is IMO. He had one of the best prose styles I’ve ever read and even had some of Dickens’s flair for characterization. (The humorous side characters of Dr. Stump and Mr. Archer in The Prisoners of September are a great example of this.) There’s this one passage in the book describing how one of the main characters, a well-meaning idealist who gets caught up in the September Massacres, can possibly justify their inexcusable violence to himself that really haunts me.

“He was in a state of considerable exaltation. He had had a great deal to drink (on previous occasions he had found it to be helpful); but this elevated his spirits rather than confused them. He was able to see over and beyond the immediate action to its ultimate purpose and consequence. The executed young woman was no more than a symbol; and yet when one said no more than a symbol, one underestimated the importance of symbols. One should have said the executed and dismembered young woman was, in herself, in her flesh, no more than a creature of sex and appetite. It was because she was a symbol that her death served a purpose…It was the knowledge, the consciousness of this great aim that made him realize that no degradation was too foul and indeed, that such degradation lent a superb satisfaction to it.”

I wonder how many people involved in the Massacres really thought that way.

While Garfield was a more cynical writer than Dickens, The Prisoners of September, like A Tale of Two Cities, has an ending that’s tragic in many ways but more hopeful and uplifting than otherwise. Seriously, it’s a great read. Go seek it out.

LikeLike

Just a few words about some things I’d like to consider at greater length, perhaps in its own post once things calm down with my work.

As Dickens moves into the latter stages of his own life, he is perhaps even more obsessed with Time and Memory than he was before…and he has always been obsessed by both. The memory of Mary Hogarth and of his childhood traumas, which come up again and again in his characters and plots, like a leitmotif, since Oliver Twist. Time passing away; Master Humphrey’s Clock, or the ticking of “the great clock in the hall” that seemed, to little Paul Dombey, to take up his Doctor’s words, “and to go on saying, ‘how, is, my, lit, tle, friend? how, is, my, lit, tle, friend?’ over and over and over again.”

A few other “time”-related notes about ATTC:

– A TALE OF TWO CITIES opened Dickens’s new periodical, ALL THE YEAR ROUND…here again, we have a relentless *circling* of time.

– The cycle of life, death, burial, resurrection.

– We have a cycle of 18 years, repeated throughout. The book begins in 1775, which is exactly the midpoint between the book’s first prologue events (the imprisonment of Dr Manette 18 years before, in 1757) and 18 years later, in December of 1793, when Sydney makes the ultimate sacrifice.

– It is noted in the book that Sydney’s sacrifice it is the end of the year, late-December. Interestingly, it was “the last day of the year” when Dr Manette had been brought to the Bastille. So, Dr Manette had been “buried” for “almost eighteen years”, just as Sydney has been effectually buried for “almost eighteen years” from the beginning of our book, until the end. Perhaps that was around the time of Sydney’s father’s death? We can only guess at the latter’s date; we only know that he was “a youth of great promise” when Sydney “followed his father to the grave” and allowed himself to be buried in Stryver’s shadow, and in hopelessness. (I have even calculated that Manette, when recalled to life by Lucie at the beginning, might have been the same age as Sydney when he dies at the end; we guess that Sydney is older than Darnay, as Stryver is older than Darnay; Stryver and Sydney are schoolfellows.)

-Mr Lorry says that as he nears the end of his own life, “I travel in the circle, nearer and nearer to the beginning.” Time has come ‘round again. (All the Year Round.)

– there are 52 prisoners to die with Sydney on that December day in 1793; just as there are 52 weeks of the year.

– the repetitive calling out of the clock hours by the mentally unstable sister who had been so wronged by the Evremondes, and her repeat of the word, “Hush!” at the end of her count, just as, later, Darnay counts down the hours to his death (“Twelve gone for ever”) and just as Sydney will repeat the word “Hush!” to the little seamstress at the end, so as not to reveal his identity.

-Words (just a few of the many) that come full circle: Resurrection/Resurrection-Man; echoes; footsteps; “better as it is”; blood/wine (Lenny, your words about the blood/wine/Eucharist are powerful!); “buried alive”/“buried how long?”; “Almost eighteen years”

Here, as Fr Matthew pointed out in our first weeks, we have a “Memory” incarnate: Sydney himself, whom Stryver nicknames “Memory.” His memory, perhaps like Dickens’s own, seems to be filled with hopeless, self-reproachful regret. Is Dickens trying to come to some peace, some sense of closure, purpose, sacrifice, as he nears his end? It is ironic that Dickens has caused so much harm to his own family; he seems to wish that he had the same capacity for sacrifice that Sydney himself does. He has given Sydney some of his own torturous inner life, but has given his initials—and perhaps his inaction—to the upright but less remarkable Charles Darnay.

Anyway, I’m throwing these things out here for reflection, as I would love to write a more polished version of these thoughts in the coming month, even if we’ve embarked on Great Expectations by then.

Man, this novel breaks my heart Every Single Time. It is simply…a revelation.

LikeLiked by 1 person